NAMES OF THE WEEK from: 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 2023 2024

11 June

Pangio juhuae Sreenath, Pradeep, Ajui, Sukumaran, Sebastian, Anto & George 2025

Pangio juhuae, holotype. From: Sreenath, K. R., B. Pradeep, K. R. Aju, S. Sukumaran, W. Sebastian, A. Anto and G. George. 2025. Discovery of a new species of troglobitic eel loach from southern India. Indian Journal of Fisheries 72 (1): 36–41.

Last year, almost to the day, we examined four fish taxa named for the young explorers (children) who discovered them (NOTW, 12 June 2024). Today we add a fifth taxon to the list.

Pangio juhuae is a new subterranean species of eel loach from Kozhikode District, Kerala State, India. The following account is quoted from a 5 May 2025 news story from The New Indian Express.

“In a remarkable blend of childhood curiosity and scientific curiosity, a four-year-old girl has become the unlikely face behind the discovery of a new subterranean fish species from Kerala. Dhanvi Dheera, fondly called Juhu, first noticed the unusual fish while playing with water collected from a well in their house during a visit to Naduvannur in Kozhikode district. Her observation prompted her mother Aswani Lalu to investigate further, which eventually led to a groundbreaking scientific revelation.

Dhanvi Dheera, nicknamed Juhu. From: The New Indian Express.

“Aswani, who used to draw water from a dugout perennial well owned by Malol Karthiayani Amma, noticed the tiny eel-like fish and informed local experts. The well, situated at an elevation of 150 m above sea level, receives continuous underground water flow from the hilly terrains of Vallora Mala and drains through a natural subterranean channel, making it an ideal habitat for rare aquatic life.

“Responding to the find, a scientific team led by Dr K R Sreenath, Director General of the Fisheries Survey of India, and Dr B Pradeep of Krishi Vigyan Kendra, Kozhikode, collected specimens. Detailed morpho-meristic and genetic analysis confirmed that the fish represented an entirely new species. The eel loach was officially named Pangio juhuae, in honour of little Juhu who first spotted it.”

Pangio juhuae is the third subterranean eel loach species discovered in Kerala in recent years. Compared with Pangio bhujia (2019) and P. pathala (2022), P. juhuae is distinguished by the presence of a dorsal fin and more pronounced eyes, suggesting it has retained more surface-dwelling traits than the other two species and might still be in the process of evolving towards a fully underground life.

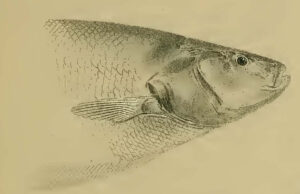

Steindachner included an illustration of the head of Sternarchella schotti with his original description, but later said that illustration needed to be corrected. The new illustration, by Eduard Konopicky, is shown here. From: Steindachner, F. 1881. Beiträge zur Kenntniss der Flussfische Südamerika’s. II. Denkschriften der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften in Wien, Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftliche Classe 43: 103–146, Pls. 1–7.

4 June

Sternarchella schotti (Steindachner 1868)

I hate getting the etymology of a fish name wrong. But I love it when readers care enough to let me know when I do and point me in the right direction. David Kelly is one such reader. He’s uncovered several mistakes in the ETYFish database over the years, some of them minor, this one major.

Austrian ichthyologist Franz Steindachner proposed many eponymic names over his long career. He usually did not identify the honorees behind these names, leaving me to make educated guesses about their identities. This time I guessed wrong.

Sternarchella schotti is an apteronotid knifefish from the Amazon River basin of Brazil, Bolivia, Colombia and Peru. Here is what I had posted about the name: “patronym not identified, probably in honor of German-American cartographer, botanist and geologist Arthur Schott (1814–1875).” I thought it was a solid guess. Based on other Steindachner eponyms I had studied, I noticed that he had a habit of naming fishes after European colleagues even if they had nothing to do with the fishes in question. Arthur Schott was the only scientist named Schott I could find who Steindachner conceivably knew and admired.

David Kelly found another Schott who has a direct connection to the knifefish that Steindachner described. And the amazing thing is, the identity of this scientist was hidden in plain sight on my computer screen. When I consulted Steindachner’s description of the fish in volume 58 of the journal Sitzungsberichte der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften. Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftliche Classe via the Biodiversity Heritage Library, I confined my attention solely to Steindachner’s paper. If I had searched “Schott” throughout the entire volume, I would have found numerous mentions of a different Schott: Heinrich Wilhelm Schott.

Undated photograph of Heinrich Wilhelm Schott.

Heinrich Wilhelm Schott (1794–1865) was an Austrian botanist who participated in the Austrian Brazil expedition of 1817–1821. The expedition was organized and financed by the Austrian Empire to celebrate the marriage of Austrian Archduchess Maria Leopoldine to Dom Pedro, Crown Prince (and later Emperor) of Brazil.

A contingent of 14 naturalists were part of the expedition, including Heinrich Wilhelm Schott and Johann Natterer (1787–1843). Natterer was a prolific collector who explored South America for 18 years. Steindachner named several fishes after him, including a related apteronotid knifefish, Sternarchogiton nattereri, that same year (1868) in a different publication. Even though Steindachner credited Natterer for collecting the holotype of Sternarchella schotti during the Austrian Brazil expedition, he almost certainly named it after Schott, who had passed away three years earlier.

My thanks to David Kelly for the correction. My apologies to Heinrich Wilhelm Schott for overlooking his connection to the fish that bears his name.

28 May

Galeus eastmani (Jordan & Snyder 1904)

Galeus eastmani. Illustration by W. S. Atkinson. From: Jordan, D. S. and J. O. Snyder. 1904. On a collection of fishes made by Mr. Alan Owston in the deep waters of Japan. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections 45: 230–240, Pls. 58–63.

The Gecko Catshark Galeus eastmani is a species of deepwater catshark (Pentanchidae) from the northwestern Pacific Ocean from southern Japan to Taiwan, and possibly also off Vietnam. David Starr Jordan and his student John Otterbein Snyder did not reveal for whom they named the shark. My best guess is that the eponym honors American geologist and paleontologist Charles Rochester Eastman (1868–1918), a specialist in fossil fishes.

Since posting that explanation about this name in 2013, I gave no more thought to Charles Rochester Eastman. That changed recently upon reading The Secret History of Sharks (2024) by paleontologist John Long. (Highly recommended.) Long includes biographical sketches about the many scientists, collectors and explorers who’ve contributed to paleoichthyology over the centuries. His account of Eastman’s life, summarized below, illustrates the sad truth that even great scientists can lead troubled and tragic lives.

Charles Eastman was born in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. He traveled to Germany to study one particular fossil shark, Cretoxyrhina mantelli, from the Late Cretaceous of Kansas, for his doctoral degree. Long describes this fossil as a “Rosetta Stone shark.” By studying this one fossil, Eastman was able to sink more than 30 scientific names of other fossil sharks that were based on isolated teeth thought to be belong to different species. Eastman’s monograph (1895) demonstrated that they all belong to different parts of this one specimen.

After Germany, Eastman took a job at Harvard University, where he published more than 100 scientific papers on fossil fishes. In October 1900, his life took a major detour when he was indicted for the murder of his brother-in-law. The two men were shooting rifles at targets. An argument broke out. The brother-in-law was shot and killed. Eastman claimed it was an accident. Eastman spent several months in prison awaiting trial. Even behind bars, Long says, Eastman was able to accomplish some “great” paleontological research. He eventually won the case and was released.

In 1918, Eastman’s life came to a sudden and tragic end. He fell from a boardwalk on Long Island, New York, and drowned. The New York Times noted the cause of death as presumed to be the result of overwork for the War Trade Board while recovering after the influenza outbreak known as Spanish flu, and that he had fallen into the sea fully clothed after fainting at the end of a boardwalk.

Long concludes his account: “Also tragic was the loss, some twenty-five years after his death, of his Cretoxyrhina fossil from Kansas that he spent several years working on in Germany. The German museum housing the fossil was totally destroyed by bombing during World War II. Eastman will always be remembered for his magnificent work on Cretoxyrhina.”

21 May

Fishes and the Piltdown Man

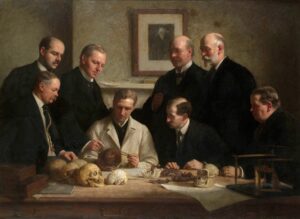

Group portrait of the Piltdown skull being examined. Back row (from left): F. O. Barlow, G. Elliot Smith, Charles Dawson, Arthur Smith Woodward. Front row: A. S. Underwood, Arthur Keith, W. P. Pycraft, and Ray Lankester. The portrait on the wall is of Charles Darwin. Painting by John Cooke, 1915.

In 1912, an amateur archaeologist named Charles Dawson (1864–1916) claimed that he discovered the “missing link” between apes and man. His evidence was a section of a human-like skull in Pleistocene gravel beds near Piltdown, East Sussex, England. Dawson contacted paleontologist Arthur Smith Woodward (1864–1944) of the British Museum. Woodward accompanied Dawson to the site. Although the two worked together, Dawson alone recovered more bones and artifacts, including a jawbone, more skull fragments, a set of teeth, and primitive tools. Woodward reconstructed the skull fragments and claimed that they belonged to a human ancestor from 500,000 years ago. He named the species Eoanthropus dawsoni (“Dawson’s dawn-man”).

In 1953, Piltdown Man was exposed as a fraud. The mandible and teeth were from an orangutan, which were combined with the skull of a fully developed, though small-brained, modern human. In addition to Dawson and his collaborators, one suspect for the fraud was Arthur Conan Doyle (1859–1930), the creator of Sherlock Holmes, who played golf at the Piltdown site.

In 2016, researchers used modern scientific methods (DNA analyses, high-precision measurements, spectroscopy and virtual anthropology) to show the bones came from two or three humans and one orangutan. The researchers concluded that the forged fossils were probably made by one man, the prime suspect and “discoverer” Charles Dawson, although others may have helped.

No fishes are named after Dawson, but two taxa have been named for others connected to the hoax.

Doboatherina woodwardi (Jordan & Starks 1901) is a silverside (Atherinidae) from the Ryukyu Islands of Japan. It’s named for Arthur Smith Woodward, the paleontologist who officially described the Piltdown man 11 years later. Woodward, author of Catalogue of the Fossil Fishes in the British Museum (1889–1901), was honored for his work on fish osteology. Although Woodward’s reputation was stained by the Piltdown scandal, and perhaps should have been more skeptical about the fossils he examined, he appears to have been an innocent victim of Dawson’s deception.

Hintonia candens, holotype, 83 mm SL. Illustration by Alec Fraser-Brunner. From: Fraser-Brunner, A. 1949. A classification of the fishes of the family Myctophidae. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 118 (4): 1019–1106, Pl. 1.

Hintonia Fraser-Brunner 1949 is a genus of lanternfishes (Myctophidae) with only one species, H. candens. The genus is named for Martin Alister Campbell Hinton (1883–1961), Keeper of Zoology, Natural History Museum (London), for “friendly help and encouragement of the most practical kind.” In 1970, a trunk belonging to Hinton was discovered at the British Museum. In it were animal bones and teeth stained and carved in a manner similar to the Piltdown finds, raising the possibility that Hinton was involved in the deception.

14 May

Ostracion Linnaeus 1758*

Juvenile Yellow Boxfish Ostracion cubicum, photographed by at the Schönbrunn Zoo (Vienna). Courtesy: Wikipedia.

Ostracion is a genus of boxfishes found in reefs and lagoons in the Indian and Pacific Oceans from the Red Sea and eastern coast of Africa to the Eastern Pacific between Mexico and Ecuador. Linnaeus proposed the genus in the 10th edition of his Systema naturae (1758), the starting point of zoological nomenclature. As was his custom, Linnaeus did not explain the meaning of the name. Nor did he coin it. Linnaeus retained the name used by his friend and colleague Peter Artedi, regarded as the father of modern ichthyology, in his Ichthyologia of 1838. Artedi had retained the name as well, used by a number of earlier scholars, including the Italian naturalist Ulisse Aldrovandi (1522–1605).

Many references, including previous versions of The ETYFish Project, tell you that Ostracion is from the Greek ὀστράκιον, meaning “little box.” The source of this explanation is Jordan and Evermann’s Fishes of North and Middle America (1896–1900). The “little box” translation makes sense since the type species, Ostracion cubicum, as its trivial name suggests, has a box-like shape. But I believe “little box” is not the correct translation and that the genus is not named for its shape despite the common name boxfish.

The Greek ὀστράκιον (ostrákion), Latinized ostracion, is a diminutive of ὄστρακον (óstrakon), meaning shell, tile, potsherd or earthen vessel in classical ancient Greek and, more specifically, shellfish in post-classical (Hellenistic) Greek. Therefore, ὀστράκιον (ostrákion), can be translated as “small earthen vessel.” But is a small “vessel” the same as a Jordan and Evermann’s “little box”? I guess that depends on how you define “vessel.” The Oxford English Dictionary defines vessel as “Any article designed to serve as a receptacle for a liquid or other substance, usually one of circular section and made of some durable material; esp. a utensil of this nature in domestic use, employed in connection with the preparation or serving of food or drink.” That doesn’t sound very box-like to me.

Adult Yellow Boxfish Ostracion cubicum, photographed by J. Petersen off Bunaken Island, North Sulawesi, Indonesia. Courtesy: Wikipedia.

Still, I’d be willing to accept the “little box” translation were it not for the fact that Ulisse Aldrovandi provides a different translation and explanation that seems definitive to me. As stated above, ὄστρακον (óstrakon) can also mean shell or shellfish. In his De piscibus marinis (1554-1555), Aldrovandi mentions “Ostracione,” a fish reportedly from the Nile River. Aldrovandi believes it to be a marine fish, however, “from the hardness of its skin, which almost imitates the shell of oysters, hence this name” (translation). (The species in question may be a related boxfish, Tetrosomus gibbosus.) The “shell” explanation nicely fits the genus, which is notable for the hard encasement of their bodies, consisting of juxtaposed hexagonal plates.

Word geeks like me are delighted to discover unexpected connections between seemingly unrelated words and names. In this case, Ostracon is etymologically linked to a word used today in English, Spanish, Portuguese, Italian and French. As mentioned above, the Greek ostracon can also mean tile or potsherd. In ancient Greece, a potsherd — a broken piece of ceramic material — was used as a writing surface, especially when voting to banish a citizen whose power or influence threatened the stability of the state. Voters write that citizen’s name on a potsherd. Those receiving enough votes would then be subject to temporary exile from the state. The practice was named for the potsherd and was called “ostracism.”

Today, we use the word “ostracize” to exclude someone from a society or group.

* Sincere thanks to Dr. Holger Funk, for helping with the Greek and reviewing an early version of the text.

7 May

The swashbuckling kelpfish

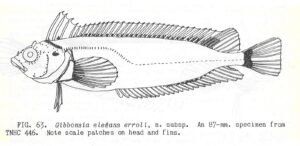

From: Hubbs, Clark. 1952. A contribution to the classification of the blennioid fishes of the family Clinidae, with a partial revision of eastern Pacific forms. Stanford Ichthyological Bulletin 4 (2): 41–165.

In 1952, ichthyologist Clark Hubbs (1921–2008), son of the legendary ichthyologist Carl L. Hubbs (1894–1979), proposed a new subspecies of Spotted Kelpfish, Gibbonsia elegans erroli, from Guadalupe Island, Baja California, Mexico. Last November, the subspecies was validated and elevated to a full species by Daniel B. Wright and ETYFish friend Giacomo Bernardi. Wright and Bernardi did not mention for whom the species is named: The swashbuckling movie actor Errol Flynn (1909–1959), the star of Captain Blood (1935), The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938), The Sea Hawk (1940), and many other Hollywood films.

Errol Flynn apparently grew up with some awareness and appreciation for marine life since his father, Theodore Thomson Flynn (1883–1968), was a marine biologist, interested in the distribution of plankton in relation to commercial fishes such as tuna. And, like many of the nautical heroes he portrayed, Errol Flynn also was a sailor. In 1946, he invited his father and Carl Hubbs, then with the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, for a cruise aboard his yacht, the Zaca.

The major purpose of the cruise was to take film footage, including underwater shots, that Flynn hoped to sell to movie companies. (Should that fail, the cruise would at least be a tax write-off.) Flynn was delighted to have Hubbs aboard. “Be assured that every possible thing will be done to make our expedition a success,” he wrote to Hubbs. “I mentioned my gratification at being able to contribute anything which in the least way might result in a step forward in the field of Marine Biology.” Flynn covered Hubbs’ expenses.

Carl L. Hubbs and Errol Flynn aboard the yacht Zaca (1946). Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego, La Jolla, CA.

In August, the expedition stopped along the west coast of Guadalupe, where Hubbs was excited to discover that many of the shore fishes were endemic to the island. That was the scientific highlight of the cruise. The rest of the expedition was “eventful,” Hubbs wrote. “Drunkenness, 2 men with broken ribs, wife beating followed by a frustrated suicide [Hubbs did not elaborate], mutiny, virtual running out of water (with tanks of water closed off somehow), engine stoppage, a very close escape from shipwreck here in Acapulco, [and] something wrong with almost everything mechanical about the ship …”. In addition, a boy-aged crewmember drove a harpoon into his foot, requiring emergency surgery.

None of this drama was shown in the 17-minute short subject, “Cruise of the Zaca,” that Flynn produced. Hubbs is given screen time and Flynn himself is seen sorting through fishes and bottles of alcohol (the preserving, not the drinking, kind). The film, released in 1952, is available as a bonus feature on the DVD of The Adventures of Robin Hood.

Carl Hubbs offered the clinid specimens to his son Clark, then a Ph.D. student at Stanford University. In his doctoral dissertation, published in 1952, the younger Hubbs described Gibbonsia elegans erroli, noting rather plainly: “Named erroli for Errol Leslie Flynn.”

According to Elizabeth N. Shor (1930–2013), Carl Hubbs’ lab assistant and Scripps historian, the elder Hubbs enjoyed re-watching Flynn’s film of the expedition in his later years. He “always chucked heartily,” Shor said, no doubt recalling the many less-than-honorable moments that weren’t filmed.

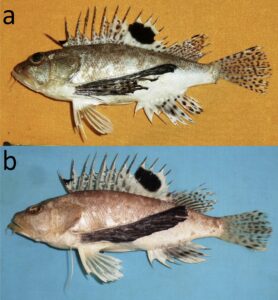

Top: Hoplisoma noxium. Photo by Steven Grant. Bottom: Hoplisoma tenebrosum. Photo by Hans Evers. Both from: Tencatt, L. F. C., W. M. Ohara, V. Carvalho, S. Grant and M. Britto. 2025. Two exquisite new species of Hoplisoma (Siluriformes: Callichthyidae) from the rio Tapajós basin, Brazil, with a discussion on the morphology of the mesethmoid within Corydoradinae. Neotropical Ichthyology v. 23 (no. 1): e240100: 1-76.

30 April

Two “noxious” catfishes

Aquarists who specialize in corydoradine catfishes have long discussed the possibility that when distressed, some species release a toxin, presumably as a defensive mechanism. This toxin poses a problem when the fishes are bagged and moved from one location to another. The water in the bag turns milky and the fish end up poisoning themselves and dying. Some aquarists dismissed this as a rumor. Others swear it’s real and has happened to them. It is most definitely real.

Earlier this month, ichthyologists reported what some aquarists have called the “cory transport toxin” in the descriptions of two new Hoplisoma species, both named for how they release a “powerful” toxin under stress, which kills any fish kept in the same bag or container during transport.

Hoplisoma noxium is so far known from three localities, the igarapé do Buriti (=igarapé Sonrizal), igarapé Miuçuzinho and igarapé do Pinto, in Pará State, Brazil. Its name is Latin (neuter) for hurtful, harmful, injurious or noxious.

Hoplisoma tenebrosum is so far known from its type locality, the igarapé Água-branca (=igarapé Ipixuna), and one of its tributaries, the igarapé Palomita, and also from the igarapé do Roncador, in Amazonas State, Brazil. Its name is Latin (neuter) for dark or gloomy, often used to describe something that is frightening or malevolent.

The authors confirmed the behavior through personal observations in the field and discussions with local fishermen, who report that specimens of H. noxium “must be separated from any other fish species just after capture, otherwise they can rapidly kill them, making the transport water milky and foamy on the surface …”.

Despite the phrase “any other fish species,” the toxin can kill conspecifics and themselves as well, especially if they’re confined to a small bag or container for an extended period of time. This is called “self-poisoning” in the aquarium hobby. This information I confirmed with two of the paper’s authors (and ETYFish fans), Steven Grant and Luiz Tencatt.

In addition, the same fisherman report that getting “stung” by them (via their dorsal and pectoral spines) is clearly more painful than any other corydoradine catfishes in the region, eventually causing “minor allergic/inflammatory processes.”

Many fishes have been named for their behavior in the wild. This is the first time that any have been named for their behavior in transport containers.

The paper in which these species are described — written by Luiz F. C. Tencatt, Willian M. Ohara, Vandergleison Carvalho, Steven Grant and Marcelo Britto — is open access. It’s vividly detailed, copiously illustrated and well worth checking out even if you’re not into corydoradine catfishes. Also worth mentioning is that the expeditions to collect the new species were funded by fishkeeping hobbyists from all around the world in crowdfunding initiatives. A round of applause to everyone involved.

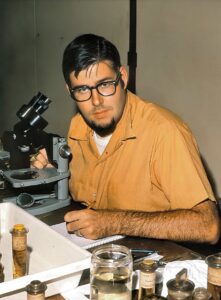

Paul V. Loiselle at the British Museum (Natural History), Sept. 2, 1971, examining West African cichlids. Photo by Michael K. Oliver, used with his permission.

23 April

Paul V. Loiselle (1945–2025)

I never met Paul Loiselle, who passed away last week at his home in New York. I never heard him speak at an aquarium show. I never had the occasion to discuss a fish name with him via email. But from the outpouring of love and praise that appeared on social media upon news of his death, it’s clear I missed out on one of the most beloved persons in fishdom.

Born in Leominster, Massachusetts, in 1945 (another source gives his birth year as 1948), Dr. Loiselle earned his B.S. in biology from the University of California. Upon graduation, he entered the Peace Corps and helped the people of Togo cultivate tilapia for food. His experience there was probably the beginning of his love for Africa and African freshwater fishes. Dr. Loiselle completed his doctoral dissertation, “An Experimental Analysis of Pupfish (Teleostei: Cyprinodontide: Cyprinodon) Reproductive Behavior,” at the University of California, Berkeley, in 1982.

I can’t improve upon the obituary posted by Tropical Fish Hobbyist, so I quote it here:

“Paul served for many years as the curator of freshwater fishes at the New York Aquarium, and was a lifelong advocate for the conservation of freshwater species, particularly in Madagascar, where he helped bring attention to the plight of endangered endemic fish. He discovered and described numerous species during his fieldwork and was honored with several named after him—a quiet testament to the depth of his contributions to ichthyology. The American Cichlid Association named the Paul V. Loiselle Conservation Fund in his honor.

“Though best known for his work with cichlids, Paul’s interests ranged broadly—including rainbowfish, killifish, and more. His deep knowledge and boundless enthusiasm made him a friend and mentor to generations of aquarists, friendships that included other giants in the aquarium hobby, such as Wayne Leibel, George Barlow, and more. For many, he was the voice of reason, always ready to offer insight, encouragement, or a well delivered joke.

“He had strong opinions—especially about scientific names and how they ought to be pronounced—no matter how everyone else on Earth said it. But that same precision and conviction fueled his dedication to the hobby and to the fish he loved.

“More than anything, Paul was a storyteller. Whether he was presenting at a conference, chatting with hobbyists, or writing for an aquarium magazine, he had a way of weaving together humor, science, and deep personal experience. He leaves behind a legacy not just of academic work and conservation victories, but of friendships, mentorships, and a better-informed, more thoughtful aquarium community.”

Here are the fish taxa that Dr. Loiselle described or co-described, most of them from Africa or Madagascar.

CYPRINIDAE

Enteromius guildi (Loiselle 1973)

Enteromius sylvaticus (Loiselle & Welcomme 1971)

ANCHARIIDAE

Gogo atratus Ng, Sparks & Loiselle 2008

CICHLIDAE

Amatitlania myrnae (Loiselle 1997)

Chromidotilapia cavalliensis (Thys van den Audenaerde & Loiselle 1971)

Cribroheros bussingi (Loiselle 1997)

Iodotropheus and Iodotropheus sprengerae Oliver & Loiselle 1972

Limbochromis robertsi (Thys van den Audenaerde & Loiselle 1971)

Paretroplus tsimoly Stiassny, Chakrabarty & Loiselle 2001

Rubricatochromis cristatus (Loiselle 1979)

Rubricatochromis lifalili (Loiselle 1979)

Rubricatochromis paynei (Loiselle 1979)

Rubricatochromis stellifer (Loiselle 1979)

BEDOTIIDAE

Bedotia leucopteron Loiselle & Rodriguez 2007

Rheocles vatosoa Stiassny, Rodriguez & Loiselle 2002

APLOCHEILIDAE

Pachypanchax arnoulti Loiselle 2006

Pachypanchax patriciae Loiselle 2006

Pachypanchax sparksorum Loiselle 2006

Pachypanchax varatraza Loiselle 2006

NOTHOBRANCHIIDAE

Pronothobranchius seymouri (Loiselle & Blair 1971)

Epiplatys togolensis Loiselle 1971

Here are the two fishes named for Dr. Loiselle, both cichlids from his beloved Madagascar:

Paretroplus loisellei Sparks & Schelly 2011 — in honor of Paul V. Loiselle, Emeritus Curator of Freshwater Fishes at the New York Aquarium, for directing the authors’ attention to this new taxon, and for his efforts to document, preserve, and educate the public regarding Madagascar’s unique and severely threatened freshwater ichthyofauna

Ptychochromis loisellei Stiassny & Sparks 2006 — in honor of Paul V. Loiselle, Emeritus Curator of Freshwater Fishes at the New York Aquarium, who collected type, for his many contributions to the understanding and conservation of Madagascar’s freshwater fishes

A third species, Cichlasoma loisellei Bussing 1989 from Costa Rica, is now considered a synonym of Parachromis friedrichsthalii (Heckel 1840).

16 April

16 April

Metriaclima vs. Maylandia

I call it the longest-running nomenclatural standoff in ichthyology.

In 1984, two aquarists, Meyer & Foerster, proposed Maylandia as a subgenus for members of the Pseudotropheus zebra complex of cichlids from Lake Malawi. They named it for cichlid enthusiast and aquarium-fish author Hans Joachim Mayland (1928–2004). In 1997, Maylandia was deemed a nomen nudum — a scientific name of an organism proposed without a sufficient diagnosis or description, i.e., a “naked name” — and replaced by Metriaclima Stauffer, Bowers, Kellogg & McKaye 1997 (metrios, moderate; clima, slope, referring to the “moderately sloped head” of its members).

Both Maylandia and Metriaclima continue to be used in both academic and aquarium references, with taxonomists and cichlid aquarists on both sides seemingly disregarding or disbelieving the other. In January 2007, the late William N. Eschmeyer recorded Metriaclima as a junior synonym of Maylandia at his Catalog of Fishes (ECoF) website, noting that Maylandia is “Incorrectly regarded as an unavailable name by Stauffer et al. 1997” and that “purported differentiated features were provided in the original description,” a decision that stands to this day. Despite the ECoF imprimatur, proponents of Metriaclima continue to use that name, describing 16 new species of Metriaclima since 2007, which ECoF editors reassign to Maylandia without comment, placing the authors’ name in parentheses to signify that the original genus has been changed. FishBase uses Maylandia. The IUCN Red List uses Metriaclima. Wikipedia redirects Metriaclima to a page on Maylandia. The Cichlid Room Companion (https://cichlidae.com), a popular resource for cichlid aquarists, recognizes Metriaclima. The Global Biodiversity Information Facility lists both genera as “accepted,” with 39 nominal species in Maylandia and five in Metriaclima, including one species listed in both genera (Maylandia nkhunguensis and Metriaclima nkhunguense). Clearly there is confusion or indecision about which name to use.

This has dragged on for 28 years. So I decided to investigate, with an open-mind, with no pre-set agenda, to see if I can bring this nomenclatural stand-off to an end.

The first thing I discovered is that quite a bit has been written about this controversy, but almost all of it in cichlid hobbyist publications and websites, most of them European, largely outside the view of professional taxonomists and the ichthyological community at large. Which may explain, at least in part, why this standoff has persisted for so long.

Last week, Zootaxa published my analysis of the debate. I find that the original description of Maylandia, although imperfectly written, does provide differentiating characters and that the publication is available per the ICZN Code (second edition, 1964) in force at the time, and that arguments against Maylandia are based on an uncompromisingly strict or literal reading of Meyer and Foerster’s original description and impractically narrow interpretations and applications of article 13a(i) of the 1964 Code. My analysis confirms that Metriaclima is a junior synonym of Maylandia.

My paper is behind a paywall. If you’d like a copy, please email me at chris@etyfish.org.

9 April

The Cyprinion corrections

Cyprinion macrostomus from Iranian waters. Photo by Farbod Emami Langroudi. Courtesy: Wikipedia.

15 April

CORRECTION to the CORRECTIONS:

According to Greek and Latin scholar Holger Funk, my statement — “In Latin, diminutives of masculine nouns are also masculine, meaning the gender of the original noun is preserved in the diminutive form; the diminutive suffix simply indicates a smaller version of the same gender” — is incorrect. While it is generally true that the gender of the diminutive matches the gender of the original noun, there are exceptions. A diminutive formed by –ion is one of them. According to Dr. Funk, the suffix –ion is always neuter, regardless of the gender of the original word. Therefore, we should disregard the changes suggested below and retain the spellings of mhalense, microphthalmum and muscatense in their original neuter forms. Heckel’s spelling of Cyprinion microstomus remains a problem. Dr. Funk suggests emending it to the neuter microstomum. Several ichthyologists dating to Berg (1949) have already adopted this spelling.

Cyprinion is a western Asian genus of minnows with nine species distributed from western Syria and the south of the Arabian Peninsula to the western tributaries of Indus River in Punjab (Pakistan). The genus was proposed by Austrian ichthyologist Johann Jakob Heckel (1790–1857) in 1843. Scholars have long treated the name as neuter in gender, which affects the spellings of specific names that are adjectives:

Cyprinion mhalense

Cyprinion microphthalmum

Cyprinion muscatense

The suffixes (-ense, –um) are neuter.

Oddly, the spelling of the type species of the genus, Cyprinion macrostomus, has remained unchanged, leading some to speculate that the specific name is an indeclinable noun (“large mouth”) rather than a declinable adjective (“large-mouthed”). Since Heckel proposed the species along with the genus, it seems his spelling was intentional, that is, he meant it to be a noun not an adjective. Some recent ichthyologists have disagreed and emended the spelling to the neuter “macrostomum.” Eschmeyer’s Catalog of Fishes retained the original spelling, stating that “macrostomus” is an indeclinable noun.

As part of my ongoing overhaul of all ETYFish entries, I reexamined Heckel’s description of Cyprinion and found compelling evidence that the name is masculine, not neuter. The evidence is a phrase at the beginning of Heckel’s German-language section of the description: “Mit der Gestalt eines jungen Karpfen” (“With the shape of a young carp”). This phrase clearly explains the meaning of Cyprinion: Cyprinus (carp genus) + –ion, from the Greek diminutive suffix –idion (-ἴδιον).

In Latin, diminutives of masculine nouns are also masculine, meaning the gender of the original noun is preserved in the diminutive form; the diminutive suffix simply indicates a smaller version of the same gender. Since Cyprinus is a masculine name, Cyprinion must be a masculine name too. The correct spellings of the three adjectival names must be:

Cyprinion mhalensis

Cyprinion microphthalmus

Cyprinion muscatensis

The suffixes (-ensis, –us) are masculine. (Note: –ensis can also be a feminine suffix.)

Based on this explanation, we can surmise that “macrostomus” is an adjective (its most common application) and not an indeclinable noun (a rare exception). Heckel knew what he was doing and spelled the name correctly.

Eschmeyer’s Catalog of Fishes accepted my explanation and changed the spellings in their database beginning with the 5 February 2025 edition.

This leaves us with a question: Who decided that Cyprinion was neuter and why? I do not know for sure, but I suspect the guilty party was the Swiss-born American zoologist-geologist Louis Agassiz (1807–1873). For reasons known only to him, Agassiz changed the spelling of Heckel’s Cyprinion to the neuter Cyprinium in 1846 (now regarded as an unjustified emendation). This may have tricked subsequent scholars into thinking that Cyprinion was neuter.

1 April

The Gulf of America!

On 20 January 2025, the President of the United States issued Executive Order 14172, officially titled “Restoring Names That Honor American Greatness,” in which the the Gulf of Mexico is renamed as the “Gulf of America.” Today, on 1 April, Executive Order 14250 has been issued, in which the names of the following fish species have been “restored” on U.S. government websites and publications:

On 20 January 2025, the President of the United States issued Executive Order 14172, officially titled “Restoring Names That Honor American Greatness,” in which the the Gulf of Mexico is renamed as the “Gulf of America.” Today, on 1 April, Executive Order 14250 has been issued, in which the names of the following fish species have been “restored” on U.S. government websites and publications:

Mustelus sinusmexicanus Heemstra 1997

Gulf Smoothhound … –anus (Latin suffix), belonging to: sinus, Latin for bay or gulf, referring to the Gulf of Mexico, type locality

New name: Mustelus sinusamerica.

Fenestraja sinusmexicanus (Bigelow & Schroeder 1950)

Gulf Skate … –anus (Latin suffix), belonging to: sinus, Latin for bay or gulf, referring to the Gulf of Mexico, type locality

New name: Fenestraja sinusamerica.

Bathyanthias mexicanus (Schultz 1958)

Yellowtail Bass … named for the Gulf of Mexico, type locality

New name: Bathyanthias america.

Coryphaenoides mexicanus (Parr 1946)

Mexican Grenadier … presumably named for its occurrence in the Gulf of Mexico

New name: American Grenadier, Coryphaenoides usa!

Also note the removal of the offensive and, frankly, very disgraceful “-anus” from all biological toponyms honoring the USA.

26 March

Salmo carpio Linnaeus 1758

Salmo carpio, female, ~28 cm TL. Photo by Bo Delling. From: Schöffman, J. 2021. Trout and salmon of the genus Salmo. American Fisheries Society, Bethesda, Maryland. ix–xxi + 1–303.

Carpio is Latin for carp, but carp have nothing to do with the Garda Lake Trout from Lake Garda in northern Italy.

The trout’s specific name is almost certainly derived from carpione, its Italian vernacular. Our resident scholar of early fish names, Holger Funk, informs us that carpione is the combination of two words, caro and pione. The origin story of the name is recounted by the Italian naturalist Hippolito Salviani in his Aquatilium animalium historiae (1558).

According to Salviani, a guest at an Italian inn or restaurant is paying his bill. He mentions that the price of the fish he just ate — a local delicacy called pione — is rather high. A diner at a nearby table overhears the conversation and jokes that the fish should be called “car-pione” instead, adding the Italian word “caro” — meaning dear, costly or expensive —to the name, i.e., “expensive pione.” After that the name pione dropped out of use and, so legend has it, was gradually replaced in favor of the nickname carpione.

My guess is that the local delicacy called pione was Garda Lake Trout. Today, that species is known as carpione del Garda in Italy.

It’s likely that Linnaeus assigned the specific epithet carpio to the species believing that was its local name, repeating a mistake made by his late colleague Peter Artedi (1705–1735), now known as the father of modern ichthyology. Linnaeus cited Artedi with information about the fish. Artedi described it “Carpio lacús Benaci,” the carp from Lake Benaco. “Benacus” was the name for Lake Garda in Roman times and is sometimes still used today. On the surface, carpio appears to be a reasonable translation of carpione. Reasonable, yes. Correct, no.

Today, “in carpione” refers to a traditional Italian method of preserving and preparing food, particularly fish, by marinating it in a vinegar- and wine-based sauce, often served cold. I wonder if the Italian diner who complained about the price was eating Salmo carpio prepared in this way.

19 March

William F. Smith-Vaniz (1941–2025)

Opistognathus rufilineatus, adult partially out of its burrow, Triton Bay, Bird’s Head Peninsula, western New Guinea. Photo by Mark V. Erdmann. From: Smith-Vaniz, W. F. and G. R. Allen. 2007. Opistognathus rufilineatus, a new species of jawfish (Opistognathidae) from the Bird’s Head Peninsula, western New Guinea. aqua, International Journal of Ichthyology 13 (1): 35–42.

I was saddened to learn that William “Bill” F. Smith-Vaniz passed away last Wednesday. We had corresponded via email several times over the years, discussing the arcana of various fish names. Then I met him in person last July at the annual meeting of the American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists. We were both staying at a different hotel than most attendees, and I found myself sitting next to him at breakfast one morning. When I caught a glimpse of the name tag on his lanyard I introduced myself. Then we pushed our tables together and chatted about – what else? – fishes. He was soft-spoken, kind, and genuinely curious about my work. He promised to attend my talk. He did. And I remember how delighted he was when he won a book he wanted at the book raffle. He did not seem sick or fragile to me. I was looking forward to seeing him again this year. A true scholar and gentlemen.

I’ve entered his name into the ETYFish database many times. By my count, he has described or co-described 129 marine-fish taxa across nine families:

Apogonidae (Cardinalfishes) – 1 species

Plesiopidae (Roundheads) – 2 species

Opistognathidae (Jawfishes) – 1 genus and 55 species

Blenniidae (Blennies) – 1 genus, 1 subgenus, 36 species

Chaenopsidae (Pikeblennies or Tubeblennies) – 4 species

Gobiesocidae (Clingfishes) – 2 species

Carangidae (Jacks and Pompanos) – 3 species

Pomacentridae (Damselfishes) – 2 species

Cepolidae (Bandfishes) – 21 species

And, as one would expect for such a renowned ichthyologist, several species have been named after him:

Pyronotanthias smithvanizi (Randall & Lubbock 1981) – the Princess Anthias of the Indo-Pacific; Dr. Smith-Vaniz, then with the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, “kindly” made his Cocos-Keeling specimens of this species available to the authors, and which he independently determined represented an undescribed species

Helcogramma billi Hansen 1986 – a triple-fin blenny from Sri Lanka; Dr. Smith-Vaniz collected all the specimens Hansen examined

Opistognathus smithvanizi Bussing & Lavenberg 2003 – the Eye-spot Jawfish, in honor of Dr. Smith-Vaniz, for his “wide variety of studies, especially dealing with carangids and for setting the standards for the systematic treatment of opistognathids”

Starksia smithvanizi Williams & Mounts 2003 – the Brokenbar Blenny from the Caribbean Sea, in honor of Dr. Smith-Vaniz, for his many contributions to our knowledge of the taxonomy of marine shorefishes and for collecting and photographing representatives of this species at St. Croix (U.S. Virgin Islands)

Percina smithvanizi Williams & Walsh 2007 – the Muscadine Darter, from the Tallapoosa River system in eastern Alabama and western Georgia (USA), in honor of Dr. Smith-Vaniz for his “outstanding” contributions to ichthyology in general and specifically for his authorship of the first book (1968) on the freshwater fishes of Alabama

Decapterus smithvanizi Kimura, Katahira & Kuriiwa 2013 – the Slender Red Scad, from the eastern Indian Ocean and West Pacific; Dr. Smith-Vaniz gave the authors morphological data of specimens belonging to the red-fin Decapterus group and made many “valuable” comments on their initial draft

Which species do I select to illustrate this entry? Since it seems Dr. Smith-Vaniz’ favorite group of fishes were the jawfishes, I selected one of the many he described (this one with Gerald R. Allen): Opistognathus rufilineatus, the Red-lined Jawfish (rufus = red or reddish; lineatus = lined) from the Bird’s Head Peninsula of western New Guinea.

Learn more about the life and career of William F. Smith-Vaniz at this memorial page.

12 March

Moxostoma ugidatli Jenkins, Favrot, Freeman, Albanese & Armbruster 2025

Moxostoma ugidatli, holotype and paratype, and Robert E. Jenkins, at the locality, North Carolina, Cherokee County, Hiwassee–Tennessee River basin, 12 August 2003.

Robert E. Jenkins (1940–2023) was arguably the world’s leading authority on suckers (Catostomidae). When he died (see NOTW, 2 Aug. 2023), he left behind a number of manuscripts and lots of unpublished data on sucker systematics and life histories. Jonathan W. Armbruster of Auburn University has been shepherding their completion and publication. The recent (18 Feb.) description of the Sicklefin Redhorse Moxostoma ugidatli is the first of these posthumous publications.

The Sicklefin Redhorse occurs in the Blue Ridge portions of the upper Hiwassee and Little Tennessee river systems of North Carolina and Georgia (USA). It’s a large sucker, with males reaching 463.2 mm SL and 2.024 kg. The authors described it as “perhaps the largest truly new North American species discovered in the last century …”.

Dr. Jenkins first encountered the Sicklefin Redhorse in 1992. He chose the “Sicklefin” moniker for the fish’s moderate to strongly falcate (sickle-shaped) dorsal fin, which easily distinguishes it from other members of the genus. Dr. Jenkins’ choice for its Latin or scientific name, falcatus, also referenced this feature. But the authors who completed and published Dr. Jenkins’ description opted for a different name: ugidatli (pronounced ooh-gee-dacht’-lee), the Cherokee word for the species, meaning “it wears a feather,” referring to this being the only species in the region where the dorsal fin is exposed above the water when spawning and its feather-like shape.

According to the authors, “We felt it important to honor the Cherokee name as it occurs on the unceded territory of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians and it is right and proper to refer to the species using the name spoken by its true discoverers.” The Sicklefin Redhorse has been known by the Cherokees Indians for centuries, and it probably served (along with other Moxostoma species) as an important food resource.

The description of Moxostoma ugidatli is open access.

5 March

Latropiscis Whitley 1931

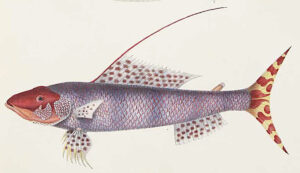

Latropiscis purpurissatus. Illustration by James B. Emery, upon which description was based. From: Richardson, J. 1843. Icones piscium, or plates of rare fishes. Part I. Richard and John E. Taylor, London. 1–8, Pls. 1–5.

I have two explanations for this name. One that’s reasonable. One that’s far-fetched … but much more fun to ponder.

Right now I am revising the etymologies of all the genus- and species-level names in the Order Aulopiformes. In doing so, I am re-researching names I couldn’t figure out during my first pass through the order. Here’s how I explained the generic name of Latropiscis purpurissatus, the Sergeant Baker, a species of flagfin (Aulopidae) endemic to Australia:

etymology not explained, perhaps latro, hireling, robber or brigand, and piscis, fish, or perhaps la-, very, tropis, keel and piscis, fish; in either case, allusion not evident

British-born Australian ichthyologist and malacologist Gilbert Percy Whitley (1903–1975) proposed the genus Latropiscis in 1931. Whitley has been the subject of several NOTW entries. He is a master of the enigmatic name.

Revisiting my 2016 entry for Latropiscis, I dispensed with the amateurish la + tropis explanation. Instead, I focused on the meaning of the Latin word latro. In addition to hireling, robber or brigand, the word can also mean mercenary or hunter. With an expanded definition of the word, I then scoured subsequent publications by Whitley that I had acquired since first researching the name. Sometimes Whitley, years after the fact, explained the meaning of one of his enigmatic names (see Milyeringa veritas, NOTW 8 March 2017). Such was not the case with Latropiscis. But in a 1966 publication written for a popular audience (Marine Fishes of Australia Volume I, Jacaranda Press, Brisbane, 142 pp.), Whitley said the Sergeant Baker “lurks amongst rocks and weeds.” Indeed, the fish is a benthic ambush predator that feeds on molluscs, crustaceans, and other fishes that live on the reef and soft-bottomed inshore waters up to 250 m deep. Since “latro” can mean “hunter,” that seems a reasonable explanation for Latropiscis: hunter + fish. “Lurks amongst rocks and weeds” evokes an image of a hunter lying in wait for the game.

As reported in previous NOTWs, Whitley was fond of coining names with historical and literary references (see Kyphosus cornelii, NOTW 9 Dec. 2020, and Malvoliophis, NOTW 7 Feb. 2024). Since Latropiscis purpurissatus has long been known among Australian anglers as the Sergeant Baker, might the name be a nod to Sergeant Baker, whoever he might be? Was Sergeant Baker a hireling? A robber? A brigand? A mercenary or a hunter? And why was this fish named after him?

Based on various Australian sources, I learned that the Sergeant Baker is believed to have been named for William Baker (c. 1761—1836), a New South Wales Marine and member of the First Fleet that founded the European penal colony of New South Wales. Described as an enthusiastic fisherman, Baker may have been the first European to catch this fish. While not a mercenary, Baker, after his Marine service, was something of a “robber.” In 1797, he was convicted of stealing a boat, and, in 1810, was dismissed from a government post for misappropriating supplies from the government store. Whitley mentioned Baker in the above-cited work but had only this to say: “Sergeant William Baker, an early colonist of Norfolk Island, must have been a florid and perhaps choleric gentleman for this rubicund fish to have been named after him.”

While I like the idea of Latropiscis being named for Sergeant Baker, the evidence is flimsy and the connection far-fetched. The evidence for the hunter + fish explanation, while still circumstantial, at least connects the behavior of the fish with Whitley’s “lurks amongst rocks and weeds” comment published 35 years later. Still, I enjoyed learning about Sergeant Baker’s obscure role in early Australian history. Even when an etymological lead is a dead-end, it is still fun to pursue.

Note: the specific epithet purpurissatus, proposed by Scottish surgeon-naturalist John Richardson (1787–1865) in 1843, is Latin for clothed or painted in purple, referring to its “general” body coloration.

26 February

Merluccius merluccius (Linnaeus 1758)

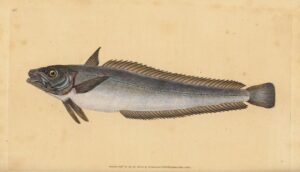

European Hake, Merluccius merluccius. Hand-colored copperplate drawn and engraved by Edward Donovan from his Natural History of British Fishes (1808).

The European Hake Merluccius merluccius occurs in the eastern North Atlantic and Mediterranean. The etymology of its tautonymous name has long been reported as “sea pike”: a combination of mare, Latin for sea, and lucius, Latin for an undetermined species of fish, usually applied to the pike. The name is said to refer to the hake’s superficial resemblance to the Northern Pike Esox lucius. But according to Holger Funk, our resident scholar of ancient fish names, this interpretation is almost certainly incorrect.

The “sea-pike” explanation dates to two important early works on ichthyology: Belon’s De aquatilibus (1553) and Rondelet’s Libri de piscibus marinis (1554). But Dr. Funk notes that some Latin texts — e.g., Pliny’s Naturalis Historia, Ovid’s Halieuticon and Varro’s Lingua Latina — refer to the fish as “merula.” In Renaissance Europe, the fish was known as merle, merlan and regional variations thereof. What does “merula” mean? It’s the Latin word for the Common Blackbird Turdus merula, another example of the frequent transfer of a terrestrial animal’s name to the name of a fish (which, by the way, has never occurred in the opposite direction).

The obvious question is: Why did the ancients name a fish that is brownish-gray for a bird that is black? Dr. Funk’s answer is that blackbirds exhibit sexual dimorphism. Males are black, females are brownish-gray.

So how did merula become merluccius? And how did “blackbird” become “sea-pike”? The answer for both appears to be the Italian version of merula — merluzzo (and other similar spellings). One can imagine that “merluccius” is a Latinization of “merluzzo.” And from there it’s easy to mistranslate “merluccius” as mare (sea) + lucius (pike). Since the European Hake is superficially similar to a pike, the explanation seems reasonable. But as Dr. Funk tells us, the “sea-pike” explanation is, linguistically, “based on very thin ice.”

“Merula” appears in the name of another gadiform (cod-like) fish from the eastern North Atlantic and Mediterranean, the Whiting or Merling Merlangius merlangus (Linnaeus 1758). The name is also applied to the Brown Wrasse Labrus merula Linnaeus 1758. In this case, the name appears to refer to the blackbird’s male (rather than female) coloration. Older specimens of Labrus merula are blackish-blue.

19 February

Channa amphibeus (McClelland 1845)

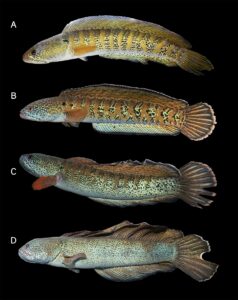

Channa amphibeus, showing live coloration. (A) 205.0 mm SL, female (B) ca. 270.0 mm SL, male (C) ca. 350 mm SL, male (D) ca. 500 mm SL, adult male. From: Praveenraj, J., T. Thackeray, N. Moulitharan, B. Vijayakrishnan, and G. K. Nanda. 2025. Lost for more than 85 years—rediscovery of Channa amphibeus (McClelland, 1845), the world’s most elusive snakehead species (Teleostei, Labyrinthici, Channidae). Zootaxa 5583 (1): 087–100.

Last month, a team of researchers from India reported the rediscovery of the Chel Snakehead Channa amphibeus, which they describe as the “world’s most elusive snakehead species.” The snakehead was officially described by John McClelland, a British medical doctor who worked for the East India Company between 1830 and 1850, based on a specimen collected from the vicinity of the Chel River basin at the foot of the Boutan mountains in Bengal, India. Channa amphibeus was last recorded from specimens collected in the years between 1918 and 1933, leading to fears that it had gone extinct. One explanation for the apparent rarity of the species is reflected in the name McClelland chose for it: amphibeus, from amphi– (ἁμφί), double, and bíos (βίος), life.

McClelland was struck by the fact that the fish appears to live both on land and in water. It occurs near the Chail (now Chel) River, he writes, but “sometimes it is met with as much as two miles from the bank of the river, where it penetrates into holes in the ground. From these it probably emerges when the ground is inundated during heavy rain, like the species of this genus so frequently found on the surface of the earth, as if they had fallen from the clouds.” (I love this image, “as if they had fallen from the clouds.” Such colorful writing is eschewed in contemporary taxonomic descriptions.)

McClelland continues:

The natives of Boutan [now Bhutan] know so well the ground in which to find these fish, that they dig them out from their holes in the following manner: a stick is passed into the suspected hole, and the earth raised sometimes to a depth of nineteen feet. When water makes its appearance the operations are suspended, and a little cow-dung is dropped into the well, this attracts the fish from their hiding place into the well, when they are easily secured. They are said to be usually found in pairs, each fish weighing about 4 lbs., and sometimes as much as two feet in length.

As you can see from the photograph, Channa amphibeus is a beautiful fish. Aquarium traders and fish hobbyists have been searching for it for decades, with no success, leading to fears that it was “lost” or extinct. But sometimes “lost” species are just exceptionally difficult to find. During a field survey in September and November 2024, three specimens of C. amphibeus were procured from a local fisher. Its apparent rarity in collections is due to a poor understanding of its fossorial (burrowing) behavior — adults live as pairs during the dry season in submerged holes originally created (and later abandoned) by crabs — and an absence of comprehensive and targeted surveys throughout its natural range. Based on information from local fishers in the region where C. amphibeus was rediscovered, the species is relished as a local delicacy.

For details on the etymological enigma of the generic name Channa, see the Name of the Week for 19 August 2020.

12 February

Leporinus lignator Boaretto, Ohara, Souza-Shibatta & Birindelli 2025

Leporinus lignator, (A) holotype, 152.96 mm SL, (B) paratype, 117.01 mm SL, (C) holotype in life, and (D) type-locality, Machado River, Madeira River basin, Brazil. From: Boaretto, M. P., W. M. Ohara, L. Souza-Shibatta and J. L. O. Birindelli. 2025. New banded Leporinus (Characiformes: Anostomidae) from the Madeira River basin, Brazil, and redescription of L. bleheri, based on integrative taxonomy. Neotropical Ichthyology 22 (4) [for 2024]: 1–32.

In the authors’ words:

“The specific epithet, lignator, is allusive to its type-locality, the Machado River, part of the Madeira River basin. In Portuguese, Machado means axe, and Madeira means wood. Lignator is Latin (m.) for a lumberjack who cuts trees into logs, often using axes. A noun in apposition.”

While I admire the cleverness behind the name, I still had fears about the conservation status of the species. After all, the formal descriptions of many Neotropical fishes conclude with dire words about their long-term survivability in the wild due to deforestation, dams or other anthropogenic impacts. Is Leporinus lignator subject to the same fate? Again, the authors allayed my fears. They write:

“Leporinus lignator is known only from a few specimens collected in a few sites, all of which are located in areas relatively well-preserved and close to several preservation areas, including the Parque do Aripuanã, the Parque Estudual de Corumbiara, and many indigenous regions. Therefore, although the species distribution is poorly known, we suggest that the conservation status of Leporinus lignator is likely to be Least Concern (LC) at this moment, according to IUCN criteria (IUCN, 2022).”

5 February

Apistus shaula Matsunuma, Seah & Motomura 2024

Fresh specimens (ca. 13 cm SL) of Apistus shaula from Karachi, Pakistan (a 15 Feb. 2014, b 4 Sept. 2018), photos by H. B. Osmany. From: Matsunuma, M., Y. G. Seah and H. Motomura 2024. Review of Apistus (Synanceiidae: Apistinae) with description of a new species from the Arabian Sea and taxonomic status of Apistus balnearum Ogilby 1910, a junior synonym of Apistops caloundra (De Vis 1886). Ichthyological Research: [1-30]. [First published online, 11 Dec. 2024.]

“The name shaula, treated as a noun in apposition, refers to the second brightest object in the constellation Scorpius.”

That’s an interesting name. But what does it mean? Why is this fish — only the second species of its genus and a distant relative of the venomous Stonefish Synanceia horrida — named for a celestial object?

When the author(s) of enigmatic names are deceased, I try to make an educated guess about their meanings, analyzing textual clues, other taxa that have the same name, or later publications by the same author(s) in which explanations or additional clues may be given. Such names have formed the subjects of many “Names of the Week.” But when the authors are alive and well, I simply send them an email. One well-known ichthyologist (I won’t say who) routinely ignores my inquiries. Another well-known ichthyologist tells me his names are “personal” and that he prefers them to remain enigmatic (but often explains them anyway). In the case of Apistus shaula, the first author, Mizuki Matsunuma of the Kyoto University Museum in Japan, wrote me back almost immediately.

According to Dr. Matsunuma, “shaula” has two explanations relative to the fish: (1) the name alludes to the adjective “second” — the second species of Apistus and the second-brightest star in the constellation Scorpius. (2) “Shaula” comes from the Arabic language and this new species is most likely endemic to the Arabian Sea.

I noticed another possible though tenuous connection between the celestial and ichthyological names. Shaula is also known as Lambda Scorpii (its Bayer designation, a Greek or Latin letter followed by the genitive form of the parent constellation’s Latin name). The constellation is Scorpius. Until 2017 or so, the stonefishes (including Apistus) had been considered a subfamily (Synanceiinae) of the scorpionfishes (Scorpaenidae).

Scorpii. Scorpius. Scorpionfish.

Coincidence?

29 January

Opistognathus cryos Su & Ho 2024

Preserved specimen of Opistognathus cryos, holotype, 65.1 mm SL. Photo by Y.-C. Hsu. From: Su, Y, and H.-C. Ho. 2024. A new species of the jawfish genus Opistognathus from Taiwan, northwestern Pacific Ocean (Perciformes, Opistognathidae). In: Ho, H.-C., B. Russell, Y. Hibino and M.-Y. Lee (Eds.) Biodiversity and taxonomy of fishes in Taiwan and adjacent waters. ZooKeys 1220: 165–174 https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.1220.123541

Last week we stated that the clingfish Melanophorichthys priscillae is the first (and only) fish species named after a movie. This recently described species of jawfish from Taiwan also has a nomenclatural connection to the cinema.

Opistognathus cryos was discovered on a beach in the northern portion of Peng-hu, a group of small islands in the Taiwan Strait off western Taiwan in the Pacific Ocean. The holotype had washed ashore, along with many other coral-reef fishes, frozen to death when a February 2022 cold snap hit Penghu. For this reason, the authors named the fish cryos, from the Greek krýos (κρύος), meaning icy cold, chill or frost, but used by the authors as an adjective (cold or chilled). The authors also proposed the common name “Frozen Clingfish” for obvious reasons, but mentioned another, perhaps superfluous, reason as well.

“Frozen Clingfish” also refers to the 2013 animated Disney film “Frozen.”

Let it go, let it go

And I’ll rise like the break of dawn

Let it go, let it go

That perfect girl is gone

Here I stand in the light of day

Let the storm rage on

The cold never bothered me anyway

Melanophorichthys priscillae, male (A) and female (B), photographed soon after collection, showing life colors. Photographs by Barry Hutchins. From: Conway, K. W., G. I. Moore and A. P. Summers. 2024. A new genus and four new species of seagrass-specialist clingfishes (Teleostei: Gobiesocidae) from temperate southern Australia. Zootaxa 5552 (1): 1–66.

22 January

Melanophorichthys priscillae Conway, Moore & Summers 2024

Three fishes have been named after characters in movies: two from Star Wars: A New Hope (Romanogobio skywalkeri, Peckoltia greedoi) and one from a 2010 Japanese animated fantasy film The Secret World of Arrietty (Malthopsis arrietty). This newly described clingfish is, I believe, the first time a fish has been named not after a character in a movie, but the movie itself.

Hugo Weaving, Terence Stamp and Guy Pearce in The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert. Photograph: Allstar/Polygram.

Melanophorichthys priscillae inhabits dense seagrass meadows in waters up to 15 m along the coast of Western Australia. It is named for the 1994 Australian road comedy film The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert, which details the journey of three heroines (two drag queens and a transgender woman) as they travel across the Australian continent in a bus named Priscilla. The name, per the authors, alludes to the bright life colors of males. As a still (shown here) from the film indicates, the male characters are indeed brightly attired.

The proposed common name is Queen Grass Clingfish.

One could make the case that Melanophorichthys priscillae is not named after the film, but for the eponymous bus in the film. If that’s the case, I can say without hesitation that this would be the first fish species in the history of fishes to be named … after a bus.

15 January

Cobitis beijingensis Sun & Zhao 2025

Cobitis beijingensis, paratype, male, in an aquarium. Photo by Zhi-Xian Sun. From: Sun, Z.-X., X.-Y. Li, X.-J. Li, J.-Y. Hao, D. Sheng and Y.-H. Zhao. 2025. Cobitis beijingensis, a new spined loach from northern China (Cypriniformes, Cobitidae). Zoosystematics and Evolution 101 (1): 55–67.

Every year we highlight the first-described new fish species of the New Year. For 2025 it is Cobitis beijingensis.

Cobitis is a genus of loaches (Cobitidae) found in temperate and subtropical waters from Europe and Northern Africa to Asia. ETYFish records 124 species and four currently valid subspecies in the genus. With the addition of C. beijingensis, the total is now 125 species (with more to be described). As the Latin suffix –ensis (from) suggests, C. beijingensis hails from Beijing, the capital city of China. You can read the original description here.

The generic name Cobitis is from kōbī́tis (κωβῖτις), an ancient Greek name for small fishes that bury in the bottom and/or are like a gudgeon or a goby. The name was first applied to loaches — for what is now known as Cobitis taenia Linnaeus 1758 — by the Renaissance scholar Rondelet in 1555.

According to Eschmeyer’s Catalog of Fishes, 406 new species were described in 2024. By our unofficial count, 37.4% of these new species belong to these five families:

Nemacheilidae … 39 new species

Oxudercidae … 38 new species

Gobiidae … 31 new species

Trichomycteridae … 24 new species

Cyprinidae … 20 new species

These diverse families keep us very busy every year updating the ETYFish Project website and database. We don’t expect that to change in 2025.

8 January

William N. Eschmeyer (1939–2024) and “Cofish”

Eschmeyer nexus, holotype, USNM 233855. Photo by Sandra J. Reardon.

William N. “Bill” Eschmeyer passed away peacefully on 30 December after a long illness. I wrote about Dr. Eschmeyer and his achievements when the “Name of the Week” celebrated his 80th birthday in 2019 (11 Feb. entry). His obituary, prepared by his family, is presented in its entirety below. Today I would like to honor Dr. Eschmeyer and his magisterial “Catalog of Fishes” by solving a nomenclatural mystery of sorts: the origin and meaning of the common name “Cofish” for the monotypic genus Eschmeyer Poss & Springer 1983, the only member of the stonefish subfamily Eschmeyerinae.

Eschmeyer nexus is known from only one specimen, a mature female 41.3 mm SL, taken in 27-43 m from Ono-i-lau in the Lau Islands, Fiji. Stuart G. Poss and Victor G. Springer named the genus in honor of Dr. Eschmeyer for his contribution to the study of scorpaenid fishes. The specific name nexus is from the Latin nectere, to tie or connect, referring to a combination of features that suggest a close relationship to several groups of scorpaenoids. The genus was placed into its own family, Eschmeyeridae, by S. A. Mandrysta in 2001. The family is now considered a subfamily of the stonefish family Synanceiidae.

Poss & Springer did not propose a common name for Eschmeyer nexus. I first encountered the common name “Cofish” for the family in the fifth edition of Nelson’s Fishes of the World (2016). I immediately noticed that the name included what appears to be an acronym of the Catalog of Fishes, COF. Is this a tribute to Dr. Eschmeyer and, if so, who came up with it? I asked Mark V. H. Wilson, one of the authors of Fishes of the World, where he got the name. He said I was not the first person to ask him this question. In fact, a previous enquirer wondered if “Cofish” is a typo. If so, a typo of what? Dr. Wilson could not say for sure where he saw the name, but guessed that he consulted FishBase and used the common name found there.

I posed the same question to Stuart Poss, who co-described the genus in 1983. Neither he, nor his co-author, proposed the common name. It “sounds like an Internet-generated error,” Dr. Poss wrote me. “Cofish – a fish that is not quite a fish but rather a cofish.”

I asked FishBase about the name and, yes, someone associated with the site coined the name as a tribute to Eschmeyer’s Catalog of Fishes. The person responsible asked that their identity not be revealed.

Note: The Wikipedia entry for Eschmeyer nexus says Mandrysta suggested the English common name “Cofish” in his 2001 monograph, citing The ETYFish Project as the source. This is incorrect. Mandrytsa did not propose any common names and we’ve never credited him with this one.

William N. Eschmeyer (1939–2024)

Bill Eschmeyer was born in 1939 in Knoxville, TN to Reuben and Ruth Eschmeyer. He spent his early years in Norris, TN where his father was the head of fisheries for the Tennessee Valley Authority, a major project of the New Deal. After Reuben suffered a fatal heart attack in 1955, Bill’s mother moved Bill and his two sisters to Maryland. Ruth raised her three children as a single mother, working full time to put all three of her children through college. Bill spent his undergrad years at the University of Michigan where he followed in his father’s footsteps to pursue a degree in marine biology. He went on to complete his doctorate at the University of Miami. In 1967, he married and moved to California, where he began his career with the California Academy of Sciences. He spent 40 years at the Academy as curator of fishes.

Bill Eschmeyer was born in 1939 in Knoxville, TN to Reuben and Ruth Eschmeyer. He spent his early years in Norris, TN where his father was the head of fisheries for the Tennessee Valley Authority, a major project of the New Deal. After Reuben suffered a fatal heart attack in 1955, Bill’s mother moved Bill and his two sisters to Maryland. Ruth raised her three children as a single mother, working full time to put all three of her children through college. Bill spent his undergrad years at the University of Michigan where he followed in his father’s footsteps to pursue a degree in marine biology. He went on to complete his doctorate at the University of Miami. In 1967, he married and moved to California, where he began his career with the California Academy of Sciences. He spent 40 years at the Academy as curator of fishes.

During his career, Bill co-wrote a popular book on fish, the Peterson Field Guide to Pacific Coast Fishes, and a total of 61 scholarly articles on fish taxonomy, but his true life’s work was creating the worldwide fish database known as the Catalog of Fishes, first published in 1990. It is difficult to underestimate the Catalog’s importance for Ichthyology, as it is the resource that everyone relies on in the field and is unique in being the only such database for vertebrate animals. For his work in systematics, Bill was awarded two lifetime achievement awards. The first was the Bleeker Award for Excellence in Indo-Pacific Ichthyology in 2009 for a “lifetime distinguished accomplishments and great contributions in the study of fish systematics in the Indo-Pacific region.” In 2019, he was awarded the Joseph S. Nelson Lifetime Achievement Award in Ichthyology from the American Academy of Ichthyologists and herpetologists. The California Academy of Sciences renamed the Catalog to Eschmeyer’s Catalog of Fishes in 2019.

Bill was especially proud that he visited every museum in the world that held a collection with type specimens (the original specimens used when describing new species). He traveled to 6 continents and well over 100 countries. He enjoyed sharing the world with his three children. He took his younger daughter on a 6-week research trip to Europe while she was in college, and later, he took all his children and their partners on several international adventures, including a memorable trip to Tahiti in 1999.

Outside of work, Bill was an avid golfer, and he even returned to Tennessee to live on a golf course for several years in the early 2000s before neuropathy in his hand forced him to give up golf for good. But the thing that he never wanted to give up was the Catalog of Fishes. In 2011, well after his official retirement, he moved to Gainesville, FL where the Florida Museum of Natural History at the University of Florida gave him an office and a computer and the title of research associate. He continued to work on keeping the Catalog updated until 2018, when his health challenges made the work too difficult. Colleagues continue to keep the Catalog up to date and it continues to be hosted by the California Academy of Sciences.

Bill moved to Massachusetts in 2018 to spend his final years near his youngest child and his three grandchildren. He was honored to learn that his eldest granddaughter is interested in fisheries biology and spent the past summer studying salmonid diseases at the University of Maine. She was equally delighted to find her grandfather’s name referenced in a paper she was reading for her internship.

Bill is survived by his two sisters, Barbara Richards and Jane Marrs; his children Lisa Eschmeyer and husband Mark Meehan; David Eschmeyer; and Lanea Tripp and husband Simon; as well as his three grandchildren Nora, Braden, and Elizabeth Tripp.

1 January

Chromis abadhah Rocha, Pinheiro, Najeeb, Rocha & Shepherd 2024

Chromis abadhah in its natural habitat in Faadhippolhu Atoll, Maldives, at approximately 110 m depth. Photo by Luiz Rocha. From: Rocha, L. A., H. T. Pinheiro, A. Najeeb, C. R. Rocha and B. Shepherd. 2024. Chromis abadhah (Teleostei, Pomacentridae), a new species of damselfish from mesophotic coral ecosystems of the Maldives. ZooKeys 1219: 165–174.

In naming this new species of damselfish, the authors express a hope for the future that seems appropriate for this, the first day of 2025.

“We also hope that this species and its habitat remain perpetual.”

The specific name of the species — abadhah (pronounced aa-BAH-duh) — means “perpetual” in Dhiveli, the local language of the Maldives. The fish occurs in deep-sea coral reefs throughout the Maldivian Archipelago, often in areas with small crevices and caves located close to large numbers of sponges. The holotype was caught using a hand net at approximately 101 m below the water’s surface, in the mesophotic zone, where sunlight is limited.

The authors chose the name in recognition of the Rolex Perpetual Planet initiative, which funded the expedition that led to its discovery. The grant was awarded to the study’s lead author, Luiz Rocha, the Follett Chair of Ichthyology and Curator of Fishes at the California Academy of Sciences. The fish’s proposed English common name is Perpetual Chromis.

Despite being relatively unexplored and hard to reach, deep-sea coral reefs in the eastern Pacific, eastern Atlantic and Indian Ocean are far from pristine. Every time they dive there, Dr. Rocha and his team see the impact of human beings. Fishing lines. Nets. Ropes. Coral bleaching. Hence the authors’ “hope that this species and its habitat remain perpetual.”

Just so you know, Rolex’s Oyster Perpetual Deepsea watches start at $14,150. The 44 mm yellow-gold model sells for $54,200.

Happy New Year!