NAMES OF THE WEEK from: 2013 2014 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 2023 2024 2025

30 December 2015

30 December 2015

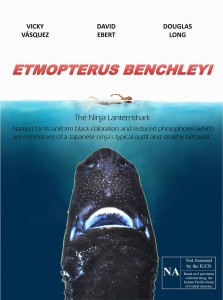

The Ninja Lanternshark, Etmopterus benchleyi Vásquez, Ebert & Long 2015

Whenever I’m asked if a movie has ever made me cry, I always answer, “Yes, just one. Jaws.”

It’s not the answer people expect. Old Yeller, maybe. Or Bambi. But Jaws?

Then I explain:

“The fish dies at the end.”

And now the author of this tearjerker, Peter Benchley (1940-2006), has been honored in the name of a new species of shark, the Ninja Lanternshark, Etmopterus benchleyi. It occurs in the eastern Pacific Ocean from Nicaragua south to Panama, with most specimens collected off Costa Rica. The depth range of collections is from 836–1443 m along the continental slope.

Benchley admitted that he carried a burden of regret for the violent backlash against sharks unintentionally instigated by his 1974 novel Jaws and subsequent 1975 movie. This inspired him to become not just an advocate for shark conservation, but also a tireless campaigner for ocean conservation at large. Co-founded by his wife, the Benchley Awards recognizes outstanding achievements in ocean conservation.

In line with Benchley’s outreach efforts, the authors of this new species asked four young shark enthusiasts, ages 8 to 14, and relatives of the first author (Vásquez) to come up with the common name. Their suggestion, the Ninja Lanternshark, refers to the shark’s uniform black coloration and reduced number of photophores, somewhat reminiscent of the typical outfit and stealthy behavior of a Japanese ninja.

The authors also created a parody of the iconic Jaws poster, shown here.

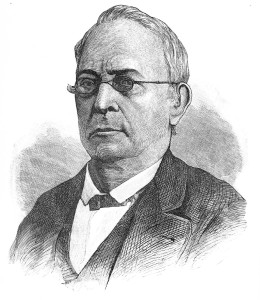

Left: Granville O. Haller. Right: His son, George Morris Haller.

23 December 2015

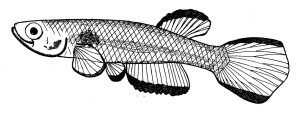

Urobatis halleri (Cooper 1863)

The Round Stingray, Urobatis halleri, occurs in the coastal waters of the eastern Pacific, where its painful but non-fatal venomous spine is responsible for numerous injuries to bathers when they accidentally step on it. In fact, that’s how this stingray got its name.

Surgeon-naturalist James Graham Cooper (1830-1902) described the ray in 1863. He named it after the “little son” of Major Granville O. Haller (1819-1897) of the United States Army, who was “wounded in the foot, probably by one of these fish, while wading along a muddy shore of the bay. The wound was very painful for some hours, though small.”

The Hallers, father and son, both led interesting lives. The elder Haller fought Seminole Indians in Florida and Mexicans in Mexico, and achieved some level of fame as a hunter and hanger of insurrecting Indians. In 1863, Haller was in charge of the defense of south-central Pennsylvania during the early days of the Gettysburg Campaign of the American Civil War. At a wine-tasting party with a few light-headed officers, Haller made an imprudent but ambiguous remark that might have included President Lincoln’s name. He was accused of uttering “disloyal sentiments” and dismissed from the Army without a hearing. Haller fled this “unjust disgrace” by moving to Seattle, Washington, where he made a fortune in real estate, lumbering, farming, and general merchandising. Sixteen years later, a joint resolution of Congress exonerated Haller of any wrongdoing and reinstated him into the Army with the rank of colonel.

The “little son,” George Morris Haller, was born in 1851. According to one account, the 12-year-old boy fought alongside his father at Gettysburg, the bloodiest battle of the Civil War. In later life George became a prominent lawyer. He organized train and utility companies and served as assistant adjutant general of the Washington National Guard. When anti-Chinese riots broke out in Seattle in 1886, Haller helped to calm the mob and forestall a forced expulsion of the city’s Chinese immigrants.

It seems George had exceedingly bad luck in water. The boy who was stung by a stingray in 1863 drowned (along with two companions) when his canoe capsized in frigid water during a duck-hunting trip in 1889.

16 December 2015

Bathylagichthys problematicus (Lloris & Rucabado 1985) and Salmo akairos Delling & Doadrio 2005

The names of these two fishes have something unusual in common. They both refer to how difficult it was for their authors to get their descriptions published.

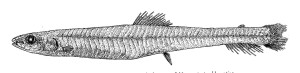

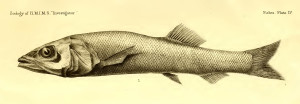

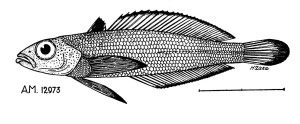

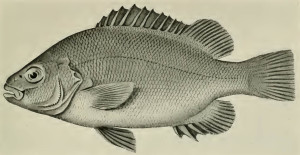

Bathylagichthys problematicus. From: Lloris, D. and J. A. Rucabado. 1985. A new species of Nansenia (N. problematica) (Salmoniformes: Bathylagidae) from the southeast Atlantic. Copeia 1985 (no. 1): 141-145.

Bathylagichthys problematicus is a deep-sea smelt (Bathylagidae) that occurs in the southeastern Atlantic (with one specimen known from southern Australia). In the original description, the authors state that the name is “derived from the difficulties that were encountered when studying the specimens.” This piqued our curiosity. What kind of difficulties?

We contacted the senior author, Domino Lloris, via email and learned that these difficulties included the following: unstable nomenclature within the family at the time and uncertainty regarding its higher-level classification; the scarcity of relevant literature; unavailable type specimens of related taxa; and a year-long editor-driven delay in getting the description to press.

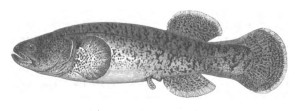

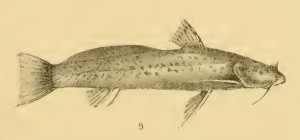

The name of Salmo akairos, a trout from Lake Ifni in Morocco, has a similar story. The authors tell us that “akairos” means “inopportune,” but they didn’t explain how this adjective applies. So we contacted the authors and received an explanation from the senior author, Bo Delling, of the Swedish Museum of Natural History.

Salmo akairos, photo by Clemans Ratschan via FishBase.

In 2002, Delling submitted his description to a different journal than the one in which it eventually appeared. At that time, the manuscript name was “Salmo ifnii,” referring to the lake where it is endemic. The description was rejected for several reasons, chief among them comments from a referee who argued against the description based on his personal opinions regarding salmonid taxonomy.

At around this time, Delling was contacted by a Swedish newspaper reporter who knew that Delling was trying to describe a new trout species from Morocco. The reporter even knew the manuscript name.

“I was rather upset regarding the treatment of my manuscript,” Delling told us. “And I got the impression that it was not opportune to describe the new species” based on prevailing notions of salmonid taxonomy.

Delling decided to ditch “ifnii” when he resubmitted his manuscript to a different journal, replacing it with “akairos,” or inopportune, which he believes reflected the circumstances at the time.

“Perhaps not the most mature thing,” Delling said, “but I was furious that the referee shared his ‘confidential’ assignment with this journalist.”

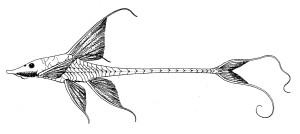

Thalassenchelys coheni. From: Castle, P. H. J. and N. S. Raju. 1975. Some rare leptocephali from the Atlantic and Indo-Pacific oceans. Dana Report No. 85: 1-25, Pl. 1.

9 December 2015

Goodbye, Thalassenchelys

We love adding names to the ETYFIsh Project. But sometimes we have to take them out.

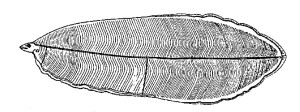

Recently, a team of Japanese researchers have linked a giant larval eel presumed to be its own species, Thalassenchelys coheni Castle and Raju 1975, to adults of the Bigmouth Conger Eel, Congriscus megastomus (Günther 1877). According to a paper in the journal Ichthyological Research, specimens of C. megastomus collected off the Pacific coasts of Japan have mitochondrial DNA sequences (16S rDNA and COI) nearly identical to those of T. coheni. The researchers also strongly suspect that T. foliaceus, the other known species of the genus, is the larval form of C. maldivensis (Norman 1939). This sinks Thalassenchelys into the synonymy of Congriscus, forcing us to delete three names from the database.

But first, let’s give these names a proper send-off by reviewing their etymologies one last time.

Eel experts Peter H. J. Castle (1934-1999) and Solomon N. Raju described the genus and its two species in 1975. They believed the leptocephali were distinct enough from other eels to warrant their own genus (and possibly their own family). The genus name is a combination of thalassa, Greek for sea, referring to its distribution in central Indo-Pacific and northeast Pacific Oceans, and enchelys, ancient Greek for eel.

Thalassenchelys coheni was named in honor of ichthyologist Daniel M. Cohen of the California Academy of Sciences, “whose description of one of the early specimens [of this species] brought attention to this larval form.”

Thalassenchelys foliaceus is the adjectival form of folium, meaning leaf, referring to the leaf-like shape of the leptocephalus.

Several other eel species are known only from their larval, or leptocephalic, forms. Will they undergo the same taxonomic fate as Thalassenchelys should they be linked to earlier-named adult forms?

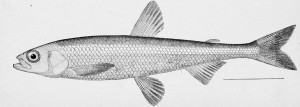

Hypomesus olidus. From: McDonald, M. 1894. Report on the Salmon Fisheries of Alaska. Bulletin of the United States Fish Commission, vol. 12, 1892.

2 December 2015

A smelly name: Hypomesus olidus (Pallas 1814)

Sometimes even the experts get it wrong.

David Starr Jordan, the “dean of American ichthyology,” is usually a reliable source for fish-name etymologies. He was trained in Latin and Greek (as all biologists were in the 1800s), and he even hired a professor of classical languages to help with the etymology sections of his four-volume masterpiece Fishes of North and Middle America (1896-1900). But Jordan and his team erred with this one.

According to Fishes of North and Middle America (vol. 1, page 525), the specific name of the Pond Smelt, Hypomesus olidus, means “oily.” This explanation has been repeated by many Fishes of … books over the years.

Unfortunately, olidus does not mean oily. It means smelly. (Oleaceus means oily.) And while the Pond Smelt does indeed have oily flesh, Pallas did not mention this fact in his description. In fact, he made a point of saying, “Totus male olet.” Translation: Smells very bad. Pallas also compared the smell to that of Salmo spirinchus (now known as the European Smelt, Osmerus eperlanus), adding that “if fresh specimens are sufficiently roasted acceptable food may be obtained.”

The European Smelt, like most members of the smelt family, smell like cucumbers. Some people like the smell. Pallas apparently did not.

Which brings us to the common name “smelt.” As fitting as it seems, “smelt” is not derived from “smell” or “smelly.” Instead, according to people who claim to know such things, it appears to be derived from the Old Dutch smalt, meaning grease or melted butter, referring to how the fish’s oily flesh gives it a “melt in your mouth” texture.

So, to summarize: While smelt in general means oily not smelly, this specific smelt’s name means smelly not oily.

(Our thanks to Ronald Fricke for helping with Pallas’ Latin.)

25 November 2015

Parotocinclus collinsae Schmidt & Ferraris 1985

Who was the first African-American honored in the name of a fish?

We haven’t studied every fish name (yet), so maybe we’re overlooking one or more names. But based on our analysis to date, it seems that the earliest (and perhaps) only such name belongs to this hypoptopomatine catfish from the Essequibo River basin of Guyana.

Schmidt and Ferraris named Parotocinclus collinsae in honor of Margaret James Strickland Collins (1922-1996), an American entomologist who specialized in the study of termites. She was stationed at the Alfred Emerson Field Station in Kartabo, Guyana. The senior author credits her for making it possible to collect fishes in Guyana.

Affectionately known as “the termite lady” to friends and colleagues, Collins was the first African-American female entomologist. Born in West Virginia, she grew up in a well-educated family, showing a keen interest in nature when she was a child. She graduated from high school early (1937) and was just 14 years old when she enrolled in college. She received her Ph.D. in zoology from the University of Chicago.

Collins taught at Howard University from 1963 to 1969 and again from 1977 until her retirement in 1983. She was a professor and dean of the zoology department at Florida A&M University in the early 1960s and also taught and was an administrator at Federal City College in Washington from 1969 to 1976. While teaching at Florida A&M, a historically black school, she became involved in civil rights efforts. After she spoke once at a nearby white university on genetics and molecular biology, the department where she was dean received a bomb threat.

By all accounts, Collins was an adventurous field biologist who felt most at home in the field. She traveled to Belize, Dominica, Guyana, Cayman Islands, Suriname, Bahamas, and British Virgin Islands collecting and studying termites. Age did not slow her down, continuing to work in the field into her 70s. In 1996, on a field trip to the Cayman Islands, Margaret Collins suffered a heart attack and passed away. She was 74.

18 November 2015

18 November 2015

What happens when a zoologist names an animal after a person but spells his or her name wrong?

Does the incorrect spelling stand? Or should the spelling be changed to reflect the author’s intention and properly identify the person who’s being honored?

It depends.

According to Article 32.5.1 of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, “If there is in the original publication itself, without recourse to any external source of information, clear evidence of an inadvertent error, such as a lapsus calami or a copyist’s or printer’s error, it [the name] must be corrected.”

In other words, if the original description does not contain internal evidence that the name was misspelled, the incorrect spelling must be retained — even if the author admits in a subsequent publication that an error was made. (Errata pages or cards that appear at the time of publication are exempt from this rule.)

Here are two cases of how Art. 32.5.1 can apply and result in different outcomes, both using patronyms coined by Austrian ichthyologist Franz Steindachner (who demonstrated on more than one occasion that he was a bad speller when it came to his colleagues’ or benefactors’ names).

In 1875, Steindachner proposed the name Prochilodus hartii for a flannel-mouth characiform from eastern Brazil. Steindachner (or his typesetter) clearly spelled the specific epithet with one “t,” and did so every time in the description. But also within that paper is a statement from Steindachner that he named the species for Charles Frederick Hartt (1840-1878), an American geologist, paleontologist and naturalist, who helped collect the type specimen during the Thayer Expedition to Brazil (1865-1866). Hartt, with two “t”s, is the correct spelling of the man’s name. So, despite Steindachner’s consistent use of one “t” when referring to the fish, his correct use of two “t”s when referring to the man in the same paper means, per Art. 32.5.1, that changing the spelling from hartii to harttii is mandatory.

In 1907, Steindacher proposed the name Psilichthys (now Pareiorhaphis) cameroni for a neoplecostomine catfish from Theresopolis, Brazil. But Steindachner did not mention for whom the species was named, nor did he mention anyone named “Cameron” in his brief description. He also did not mention anyone named “Calmon,” which is most unfortunate since one year later Steindachner changed the spelling to calmoni and indicated that the species was named for Miguel Calmon du Pin e Almedia (1879-1935), Brazil’s Minister of Agriculture, Commerce and Industry, as a “token of [Steindachner’s] respect and gratitude” (translation).

In this case, Art. 32.5.1 preserves the original incorrect spelling because there is no internal evidence in Steindachner’s first description that the name was misspelled. (Although it should be noted that some catfish taxonomists choose to ignore Art. 32.5.1 and spell the name calmoni.)

Don’t feel too bad for Calmon. Steindachner named another fish after him in 1908 — the piranha Serrasalmo (now Pristobrycon) calmoni — and this time he got the spelling right.

Narcetes erimelas. From: Alcock, W. A. 1892. Illustrations of the Zoology of H.M. Indian Marine Surveying Steamer Investigator. Part I. Fishes. Calcutta: Superintendent of Government Printing.

11 November 2015

Narcetes erimelas Alcock 1890

Deep-sea fishes pulled to the surface are probably not going to be very lively. This apparently was the case when physician-naturalist Alfred William Alcock (1859-1933) proposed a new genus and species for two specimens of slickheads (Alepocephalidae) collected from 740 fathoms (1353 m) in the Laccadive (or Lakshadweep) Sea between southern India and the Maldives.

Alcock named the species erimelas (eri = very, melas = black) for its deep-black coloration. The generic name means numb or numbness. It’s from the ancient Greek word narke, the root of the electric ray genus Narcine Henle 1834 and the present-day word “narcotic.”

The specimens that were brought on board, Alcock wrote, “were in a cataleptoid state, the whole muscular system being quite rigid, and cutaneous excitation eliciting no responsive movement.”

“Cutaneous excitation” — is that science-speak for poking with a stick?

4 November 2015

4 November 2015

Ricola Isbrücker & Nijssen 1978

No, the monotypic loricariid catfish genus Ricola is not named after the Swiss manufacturer of cough drops and breath mints. Instead, the name is an anagram of lorica, a curiass, corselet, or coat of mail, the root of Loricaria (which was named for the bony plates on the back and sides of L. cataphracta). According to Isbrücker and Nijssen, Ricola and Loricaria are “very similar” in all external characters except for barbel structure and shape and number of teeth. Hence the anagrammatic name.

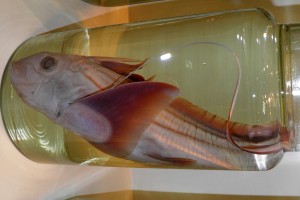

A spirit in spirits. Chimaera phantasma in the Science Museum of Far Eastern Federal University (Vladivostok). Photo by A. C. Tatarinov, courtesy Wikipedia.

28 October 2015

Some ghoulish names for Halloween

Chimaera phantasma Jordan & Snyder 1900 — The Silver Chimaera of the Western Pacific. Its name, meaning phantom or apparition, probably refers to its striking appearance in life (silvery, with jet-black bands down the sides) and/or its overall ghoulish appearance common to all chimaeras.

Hydrolagus lemures (Whitley 1939) — The Blackfin Ghostshark of the Indo-West Pacific. “Lemures” means “ghost of the departed” and presumably refers to the vernacular “ghostshark,” so named for their large googly eyes, faintly luminescent body, tapering tails and overall ghoulish appearance.

Apristurus manis (Springer 1979) — The Ghost Catshark of the North Atlantic. The name manis, Latin for ghost or shade of the departed, refers to the shark’s grayish-white color

Lepidocephalus spectrum Roberts 1989 — Spectrum means spectral, an appropriate name for the Blind Spirit Loach of western Borneo. It refers to the “ghastly or ghostlike character” of its eyelessness and creamy or pinkish white coloration.

Bryconamericus uporas Casciotta, Azpelicueta & Almirón 2002 — This characin from the Uruguay River basin of Argentina and Brazil is named for the Guaraní word for an “animal-shaped ghost of the water who care[s for] streams, ponds, falls, and swamps,” presumably referring to its occurrence in small falls and pools with clear, rapid water.

Creagrutus phasma Myers 1927 — Like phantasma (see above), this name means apparition or specter, but it does not refer to this Río Negro characin’s appearance. Instead, Myers selected the name because he believed that the species was a “veritable ghost of” the sympatric genus Creagrudite (now considered a synonym of Creagrutus).

Tembeassu marauna Triques 1998 — This gymnotid, or knifefish, from the Rio Paraná basin of Brazil is named for the native Tupí word for ghost, maraúna. It refers to how the fish is “hidden” in its habitat.

“Synodus.” From: Gronow, L. T. 1756. Museum Ichthyologicum, sistens piscium indigenorum et quorundam exoticorum, qui in Museo Laur. Theod. Gronovii adservantur, descriptiones, ordine systematico; accedunt nonullorum exoticorum piscium icones, aeri incisae. v. 2.

21 October 2015

The mystery of Synodus and Synodontis

The precise meanings of names that date to antiquities are always difficult to pin down. We often don’t know how these names originated or how they were first applied. And we often have an incomplete record of how the names have been reapplied to different species over the years. Synodus is a case in point.

Synodus is the type genus of the Lizardfish family Synodontidae. It appears to be a composite word derived directly from the Greek words syn (= together) and odous (= tooth). The name was applied to the Diamond Lizardfish by Gronow in the second volume of his Museum Ichthyologicum in 1756, in a pre-Linnaean publication. Our reading of Gronow’s Latin indicates that he did not explain how the teeth are “together.” Officially, the name dates to Linnaeus 1758, who created the binomial Esox synodus for Gronow’s Synodus.

Gronow published another description of Synodus in his Zoophylacii Gronoviani of 1763. Here he provided a sentence that could explain his choice of the name: “Dentes validissimi, praelongi, contigui, conferti in maxillis, palato, lingua & faucibus.” Our translation: “Their teeth are very strong, extraordinarily long, continuous, and crowded together in the jaws, palate, tongue and throat.” It’s the “crowded together” part that intrigues us. Does Synodus refer to teeth that are close together? Maybe. But there’s another explanation to consider.

Gronow wasn’t the first to apply “synodus” to a fish. The name appears in Pliny the Elder’s Naturalis historia (77-79 AD), one of the very first works on natural history: “Synodontitis is a stone found in the brain of the fish known as synodus” (translation). This “stone” was probably an otolith (which in ancient times were used in folk medicine and meteorological divination), but no one knows for sure what kind of fish Pliny was referring to. A footnote from Bostock & Riley’s 1857 translation suggests it was a bream from the genus Sparus, but they do not provide a source for their supposition. However, Bostock & Riley did provide a compelling explanation for the name. They say Synodus refers to “its teeth meeting evenly, like the jaw-teeth, and not shaped like those of a saw, so formed that the teeth of one jaw lock with those of the other.”

David Starr Jordan, the dean of American ichthyology and one very interested in fish-name etymologies (see last week’s Name of the Week), accepted this explanation. In 1882, Jordan said that Synodus is the “Ancient name of some fish,” derived from the Greek synodus, i.e., “teeth meeting, not shutting past each other like scissors.” We’re no experts on the dentition of Synodus, but we’ve yet to find any account of the genus that describes its teeth in this manner.

The similarity of the familial form of the name Synodus — Synodontidae — with that of the African upside-down catfish genus Synodontis has understandably led many to assume that the catfish name also means “together tooth.” But according to Cuvier’s Le Règne Animal (1816), Synodontis is the “ancient name for an undetermined fish from the Nile” (translation). (And yes, Synodontis does occur in the Nile.)

Do Synodus, Synodontis and Synodontitis (the otolith) all descend from the same word and/or the same fish? Or is their similarity an etymological coincidence? We will continue to research this name, but for now we’ve run out of places to look.

Stout Blacksmelt, Pseudobathylagus milleri. Courtesy: BIO Photography Group, Biodiversity Institute of Ontario.

14 October 2015

Pseudobathylagus milleri (Jordan & Gilbert 1898)

Has a scholar or enthusiast of fish-name etymologies ever had a fish named in his or her honor? The answer is … yes!

Jordan & Gilbert named this deep-sea smelt from the subarctic North Pacific and the Okhotsk and Bering seas after Walter Miller (1864-1949), Professor of Classical Philology at Stanford University, where Jordan was president. Miller was honored for his “intelligent interest” in zoological nomenclature.

The year before, in 1897, Miller published a paper in the Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences called “Scientific Names of Latin and Greek Derivation.” In the first paragraph, Miller said that Jordan hired him to “review and verify the etymologies of the names of the fishes described” in Jordan and Evermann’s four-volume magnum opus, The Fishes of North and Middle America (1896-1900). [Note: this species was described in volume three.]

Miller, apparently, was quite the puritan when it came to proper Greek and Latin usage, lamenting how “scientific writers have arbitrarily departed from the philologically correct method of nomenclature established by Linnaeus” (while noting that Linnaeus himself was not without nomenclatural sin). Especially grating to Miller was the practice of some taxonomists to combine Greek and Latin words in the same name. Such names, he complained, “are enough to make one’s hair stand on end.”

Miller railed on Rafinesque, who coined “philological monstrosities” such as these names for two genera of common North American freshwater fishes — Semotilus (creek chubs) and Lepomis (sunfishes) — names that “demand the constant apology of those who use them” because they do not “give correctly the idea the author may have intended.”

We’re confident that Miller had no qualms with the construction of “milleri.”

Dallia delicatissima. From: Nordenskiöld, A. E. 1881. Vegas färd kring Asien och Europa. Vol. 2. Stockholm: F. & G. Beijers Förlag.

7 October 2015

Dallia delicatissima Smitt 1881

Sometimes the meaning of a fish name is hiding in plain sight. In this case, the meaning of the name was revealed on the two pages preceding the page we were focusing our attention on.

Dallia delicatissima is a mudminnow (Umbridae) that occurs in the Chukotski Peninsula of Russia and Port Clarence, Alaska. It’s part of a fascinating genus of freshwater fishes rumored to be able to survive being frozen alive. Such claims have not held up to scientific scrutiny, but the species does occur in some of the coldest habitats of any freshwater fish.

The specific name is credited to Swedish zoologist Fredrik Adam Smitt (1839-1904), but the name was published in a general-audience book, Vegas färd kring Asien och Europa (The Voyage of the Vega Around Asia and Europe) written by Finnish explorer Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld (1832-1901).

“Delicatissima” means most delicious, but the description (in Swedish) contained a passage that confused rather than clarified. Nordenskiöld compared the species to its European relatives in the genus Umbra:

It is remarkable that the European species [called dog-fish] are considered uneatable, and even regarded with such loathing that the fisherman throw them away as soon as caught because they consider them poisonous, and fear that their other fish would be destroyed by contact with it. They also consider it an affront if one asks them for dog-fish. If we had known this we should not now have been able to certify that Dalia delicatissima, Smitt, truly deserves its name.

Why did the species deserve to be named “most delicious”? The passage did not say. We reread it several times, but apparently something was being lost in translation. Then, quite by accident, we glanced at the page that immediately preceded it. Here Nordenskiöld provided an account of the Chukches people of Russia catching fish from a freshwater lagoon:

The fish were transported in a dog sledge to [our ship], where part of them was placed in spirits for the zoologists and the rest fried, not without protest from our old cook, who thought that the black slimy fish looked remarkably nasty and ugly. But the Chukches were right: it was a veritable delicacy, in taste somewhat resembling eel, but finer and more fleshy.

On the page before that, Nordenskiöld described the fish as “exceedingly delicious.”

Next time we go out for seafood, we’re trying the mudminnow!

30 September 2015

Gobius (now Periophthalmodon) schlosseri (Pallas 1770)

What makes this name special? It was the first specific epithet in ichthyological literature to honor a person using the patronymic “i.” Many, many fish names have been coined since then using the same construction, honoring colleagues, professors, spouses, collectors, explorers, philanthropists, and luminaries from nearly every walk of life. But this one was the first.*

Naturalist and explorer Peter Simon Pallas (1741-1811) proposed the name in Part 8 of his series Spicilegia Zoologica (“Zoological Gleanings”). The species in question is the Giant Mudskipper of the Indo-West Pacific, which is noted for leaving the water and skipping across tidal mud flats during low tides.

Pallas said the name honors “the celebrated man and my very close friend J. Alb. Schlosser, who received [this species] among fishes from Ambon [Indonesia] and kindly transferred them to me.” (Our thanks to Ronald Fricke for help in translating Pallas’ Latin.)

“J. Alb. Schlosser” is Johann Albert Schlosser (1733-1769), a Dutch physician, naturalist, and collector of natural history objects. His primary field of study was what is now called biomineralogy; in fact, Schlosser was the first to experimentally document evidence for the presence of iron in the salts of human urine. While traveling the world collecting minerals, he also collected fossils and animals. In doing so, he provided the first description of the Brine Shrimp, Artemia salina, in 1755. Many of Schlosser’s specimens from the Indo-West Pacific, including the Giant Mudskipper, came from two friends who worked as ship surgeons for the Dutch East India Company.

The last years of Schlosser’s relatively short life were tragic. His first wife died young in 1766, less than half a year after she gave birth to a daughter. His second wife was not yet 19 and pregnant when she died on 2 March 1769. Schlosser died a few weeks later on 20 March. He and his second wife were both victims of a scarlet fever epidemic.

Who was the first person honored in all of zoological literature? We don’t know. (Anybody up for figuring that out?) But we do know that Pallas named a tunicate — Botryllus schlosseri — after his good friend four years earlier in 1766.

*Pallas named two other fishes in the same publication using the patronymic “i”, but schlosseri came first (page 3). The other two are Gobius koelreuteri (page 8, now a junior synonym of Periophthalmus barbarus) and Gobius (now Boleophthalmus) boddarti (page 11).

23 September 2015

23 September 2015

Loraxichthys lexa Salcedo 2013: The complete and unabridged story behind its name

10/21/15 UPDATE: Molecular phylogenetic evidence published by Lujan 2015a and Lujan 2015b, combined with the overall similarity between Loraxichthys and some species of Chaetostoma, indicate that the former genus is a junior synonym of the latter.

When Norma J. Salcedo published the description of this rare loricariid catfish from Huánuco, Peru, in the journal Zootaxa, the etymology section explained the interesting name:

Lorax is the name of a fictitious character, created by Theodor Seuss Geisel, that plights for the environment. Ichthys is based on a Greek noun meaning fish. Loraxichthys refers to the fish that speaks for other fishes. The species lexa is in recognition of Alexandra Keane, sustainability activist, currently a Political Sciences student at the College of Charleston. The specific epithet is used as a noun in apposition.

But the published etymology did not explain the full story behind the name’s meaning and significance. For example, how does Loraxichthys “speak for other fishes”? And why was a political science student honored in the specific epithet? We posed these questions to Dr. Salcedo, who informed us that an earlier draft of her description elaborated on the name’s etymology but that a reviewer found it too “emotional” and asked that it be shortened. Here is the original draft:

Lorax is the name of a fictitious character that speaks for the trees, the birds, and the fishes and tries to stop the destruction of their habitat. Ichthys is Greek for fish. The species lexa honors Alexandra Keane, a third year student and Political Sciences major at the College of Charleston, who wants to learn more, about trees, birds, and fishes, to make this planet a better world for all. The specific epithet is used as a noun in apposition. In combination Loraxichthys lexa refers to the fish that speaks for other fishes, which might become extinct, unless there are more people, like Alexandra, that care enough about them.

During our email exchange, Dr. Salcedo shared additional details about the name which, with her permission, we share with you here.

I have a six-year-old child and we went to see The Lorax together, a movie for children. Then I learned about Dr. Seuss and the book he wrote where the Lorax speaks for the trees, and the birds, and the fish, etc. The fish in question inhabits, apparently, only two small streams that drain into the Huallaga River. This is an endemic lineage that is as unique as the plants that live on one slope of the mountains. By the time I was describing this species I learned that there was a team of biologists doing an environmental impact study, required by the Peruvian government, so a dam could be built. This dam will compromise the water flow in the Huallaga River basin. The lists of species generated in these kinds of studies often reveal new undescribed species or species we are uncertain about simply because we know so little about them. The genera related to this genus (e.g., Chaetostoma, Lipopterichthys) are such a taxonomic challenge that identifications to the level of species is very hard.

Nevertheless, Loraxichthys stands out (like the Lorax!) with its long evertible odontodes and the funny folds on its pelvic fins. Its osteology is fascinating! Its pelvic girdle is intermediate between Ancistrus and Chaetostoma. It lacks a nuchal plate. This fish speaks for other fishes in that drainage, those endemic organisms that share the unique environment that led to the evolution of such particular and peculiar morphology. I hope people will talk about it, learn about the Huallaga River and stop the construction of dams in the Andes. This might not happen unless (have you read The Lorax?) somebody who really cares, takes this matter into his/her hands.

About the specific epithet. It breaks my heart to see students coming and going through college without any interest in learning. I feel fortunate to have had many wonderful students, but one student in particular caught my attention while she was taking biology for non-majors (I was teaching the laboratory portion; she was in my section). She was eager to learn biology, but not only that, she was eager to do things that could translate into change. That is when my brain went boom! This is it. She is the reason for “unless.” It is the engineers, politicians, and economists who make decisions in environmental policies without even trying to understand biological processes. This is why liberal arts education is so important.

Of course there was an emotional discourse in the etymology! But we are scientists, and are not allowed to express feelings on paper.

Dr. Salcedo’s comments about liberal arts majors reminds us of famed Harvard entomologist Edward O. Wilson, who insisted on teaching an introductory biology class to non-biology students. Because it’s these students — the future lawyers, politicians, developers, bankers, investors, engineers, corporate executives, and so — who will be setting the priorities and making the choices that decide the fate of our planet and its biodiversity.

Pagothenia antarctica (=P. phocae). From: Nichols, J. T. and F. R. La Monte. 1936. Pagothenia, a new Antarctic fish. American Museum Novitates No. 839: 1-4.

16 September 2015

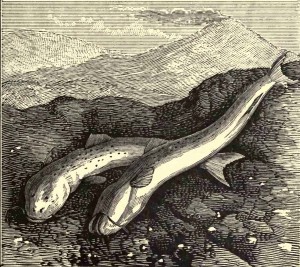

Pagothenia phocae (Richardson 1844) with a note on Notothenia

Many fish species are named after the person who first collected the species, or the person who collected the specimen(s) that comprise the type series. This nothothen, or cod icefish, from the Antarctic, was named for its collector, too.

On the 14th of January, 1842,” wrote surgeon-naturalist John Richardson, “when the ships were embayed among ice, in the 65th parallel of south latitude, and about the 155th west meridian, a seal was taken with twenty-eight pounds of fish in its stomach. The fish were of two kinds, one a Sphyraena, the other a Notothenia [now Pagothenia], of which there were many mutilated individuals. Dr. [Joseph Dalton] Hooker made a careful drawing of the most perfect, and put several examples in spirits …

In this case the collector was a seal, a Leopard Seal, to be precise, Hydrurga leptonyx. Phoca is a latinization of the Greek phoke, meaning seal. “Phocae” means “of a seal.”

Richardson provided other interesting details about the hardships of preserving Antarctic fishes during their long voyage back to England:

The specimens thus obtained filled many casks, and numerous jars and bottles, and it were greatly to be wished that so much industry had met with the full measure of success that it deserved; but we have to regret that, during a voyage protracted for upwards of four years and a half, including every possible change of climate, and during which the ships were buffeted by many severe gales, and sustained innumerable shocks in forcing their way through the ice-packs of the Antarctic Seas, the specimens suffered very severe damage. Owing to the deterioration of the spirits in jars that were crowded with fish, and the long continued action of the brine, where that liquid was employed, very many specimens entirely perished, or merely fragments of skeletons could be rescued from the mass.

The meaning of the generic epithet Pagothenia refers to the fish’s habitat. Described by John T. Nichols and Francesca La Monte in 1936 for the species Pagothenia antarctica (now a junior synonym of P. phocae), the authors did not provide an etymology. But pagos is Greek for frost, and forms the root of the word pagophilia, i.e., one who thrives or prefers to live in ice. “–thenia” appears to be derived from the Greek euthenia, meaning abundance. Hence, a fish that’s abundant in ice.

It’s possible that the –thenia part of Pagothenia alludes to or was inspired by Richardson’s original genus, Notothenia. According to FishBase, Notothenia translates as “noton = filament + Greek, adverbial particle, then, that denotes distance or removal.” Unfortunately, FishBase is wrong. Actually, notos means south and refers to the fish’s abundance in the Antarctic. In fact, Richardson explicitly said that the name refers to the genus’ “high southern habitat, where it is probably represented by one or more species in almost every degree of longitude” (i.e., within the Antarctic circle).

Wherever FishBase got their etymology of Notothenia, it clearly wasn’t the publication in which the name was coined.

Astroblepus simonsii. From: Regan, C. T. 1904. A monograph of the fishes of the family Loricariidae. Transactions of the Zoological Society of London v. 17 (pt 3, no. 1): 191-350, Pls. 9-21.

9 September 2015

Astroblepus simonsii (Regan 1904)

Last week we featured an astroblepid (climbing) catfish from the Andes with an interesting name. This week we feature another astroblepid catfish from the Andes, also with an interesting name. The story behind this name involves a murder.

In his description of the catfish, British ichthyologist Charles Tate Regan said that the type specimens were collected at Huaras, Peru, at an elevation of 10,700 feet, by the “late” Mr. P. O. Simons. We didn’t know who Simons was, and Regan’s mention of the word “late” piqued our curiosity. What follows is a brief account of Simons’ life and death assembled from three different sources.

Born in Wisconsin in 1869, Perry Oveitt Simons moved to California in 1886 and later attended Stanford University, where he studied electrical engineering. During the summers he helped zoology students collect animals in the mountains of California and Arizona. He was so good at collecting animals at high elevations that the British Museum (Natural History) hired him in 1898 for a three-year expedition to the Andes of South America. Simons sent back valuable collections of animals, several of which — including three lizards, a snake, and a frog — were named in his honor.

While collecting in the Andes, Simons feared for his life. In his letters home he worried about the “irresponsible natives” who helped him in various ways. He mentioned two unsuccessful attempts on his life. One time he discovered that his meal was poisoned, for he was made sick by eating a little and his dog was killed by it. At another time he was robbed of everything he had and put in prison by the local authorities as a vagabond and on general suspicion. For several weeks he was unable to get word to anyone until he finally notified the British Consul, who had him released.

Undaunted, Simons set out on what would be his final journey in December 1901. He started out on foot from Argentina for Valparaiso, having first shipped his collecting materials ahead. On the night of December 20, 1901, while Simons was on the trail across the Paramillo de las Cuevas, near Cuevas, Mendoza, Argentina, he was murdered by his Chilean guide, one Esteven Paves, with the motive of robbery. Paves is said to have struck Simons on the back of the head with a “penca,” or loaded knot at the end of a rein, and then to have driven a spike through his forehead. Paves threw Simons’ body into the Mendoza River, where it was later recovered and buried, and made off with Simons’ outfit. The murderer was later apprehended and sentenced to imprisonment in Mendoza, finally dying in prison in January 1908.

News of Simons’ brutal death shocked and saddened his colleagues. British zoologist Oldfield Thomas eulogized Simons. “Brave to a fault,” he wrote, “cheery and enthusiastic, fond of a wild life, successful as a trapper, painstaking, systematic, and extraordinarily rapid in his work, Mr. Simons was the perfection of a collector, and we shall not easily find his like again.”

Sources:

Anonymous. 1902. Killed by his guide. The Daily Palo Alto. Vol. XX, No. 85 (12 May). Page 4.

Anonymous. 1903. [Untitled obituary]. The Auk. Vol 20. Pages 94-96.

Burt, C. E., and G. S. Myers. 1942. Neotropical Lizards in the Collection of the Natural History Museum of Stanford University. Stanford University Publications, Biological Sciences, vol. VIII, no. 2. Stanford, Ca.: Stanford University Press.

Artist’s rendering of Astroblepus cyclopus, ejected from a volcano. From: Pouchet, F.A. 1883. The Universe; or, The Wonders of Creation. 7th ed. Portland, Me.: H. Hallett and Company.

2 September 2015

Astroblepus cyclopus (Humboldt 1805)

With a name like cyclopus, you’d expect this astroblepid (or climbing) catfish from the Andes of Ecuador to have only one eye. Or at least look like it has one eye. But no, the name has nothing to do with eyes. Instead, it has to do with Humboldt’s belief that living specimens of the catfish are regularly expelled from the volcanoes they live under or inside.

Let me explain.

German naturalist Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859) spent five years exploring the New World, including parts of present-day Ecuador, Venezuela, Brazil, Cuba, Mexico, and a brief visit to the United States. He contributed at least 20 new fish taxa to the literature, including two new catfish genera that are still valid today, Eremophilus (Trichomycteridae) and Astroblepus (Astroblepidae). Humboldt was quite amazed by the latter.

In his description of the fish (herein translated from the French), Humboldt talked about a chain of active Andean volcanoes that frequently eject enormous quantities of mud. While none of these “volcanic inundations” took place during his visit, he learned from town archives and from “several very well informed persons, who have successfully devoted themselves to the physical sciences,” that these volcanoes also eject “an innumerable quantity of fish,” and have done so many times over the years.

In 1691, for example, one volcano “threw out thousands on the field of the city of Ibarra. The putrid fevers which commenced at that period were attributed to the miasma which exhaled from these fish, heaped on the surface of the earth and exposed to the rays of the sun.” Again, in 1698, “thousands of these animals enveloped in argillaceous mud were thrown over the crumbling borders” of a volcano that sunk back into the earth.

“Some Indians have assured me,” Humboldt wrote, “that the fish vomited by the volcanoes were sometimes still living in descending along the flank of the mountain: but this fact does not appear to me sufficiently proved …”. The Indians, however, did convince Humboldt that the ejected fishes were identical to those found in rivulets at the foot of these volcanoes. This led Humboldt to surmise that Ecuador “contains great subterranean lakes which conceal these fishes,” with small outlets that occasionally allow them access to the surface.

Humboldt’s claim that the catfish lives in subterranean waters has not panned out; indeed, the species appears to be quite common in surface waters. The even more fantastic claim that it is ejected from volcanoes — presumably, when the presumed subterranean waters heat up, condense and push through vents in the sides of the volcanoes — has not been verified either. In fact, we’ve seen only passing reference to Humboldt’s extraordinary account in modern literature.

So how did Pimelodus cyclopus (now Astroblepus cyclopus) come by its specific name? Humboldt offered no explanation, but anyone well versed in Greek mythology — as Humboldt and other scholars of his time period almost certainly were — would see the connection right away.

Cyclops, the one-eyed giants who forged Zeus’ thunderbolt, Hades’ helmet of invisibility, and Poseidon’s trident, lived inside the volcano of Mt. Aetna (or Etna) of Sicily.

Photographs of live (A) Sebastes diaconus and (B) S. mystinus in the Oregon Coast Aquarium, Newport, Oregon, USA. From Frable et al. 2015.

26 August 2015

Sebastes diaconus Frable, Wagman, Frierson, Anguilar & Sidlauskas 2015

It’s nice when modern-day ichthyologists coin names that complement those coined by their predecessors. Here’s a recent case:

In 1881, Jordan and Gilbert named the Blue Rockfish, Sebastichthys (now Sebastes) mystinus, which occurs in Pacific waters from southeastern Alaska south to northern Baja California. Jordan and Gilbert did not explain the etymology of “mystinus.” But in 1884, Jordan provided a clue: “The Portuguese at Monterey call it ‘Pesce Pretre,’ or Priest-fish, in allusion to its dark colors, so different from those of most of the other members of the family.” Mystinus is derived from mystes, the Latin word for initiated one, or priest.

Fast-forward to the present. Researchers from Oregon and California have taken another look at S. mystinus and conclude that it represents two species on the basis of molecular and morphological data. They have named it Sebastes diaconus, the Deacon Rockfish, from the Latinized ancient Greek word for an acolyte or assistant to a priest.

The name complements the species name of S. mystinus while highlighting the similarity between the two species.

19 August 2015 [revised 26 October 2016]

19 August 2015 [revised 26 October 2016]

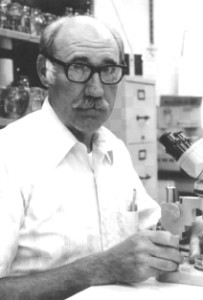

Oneirodes basili Pietsch 1974

On 24 May 2015, marine biologist Basil Nafpaktitis passed away in hospice at his home in Charlottesville, VA , surrounded by his family and his wife of more than 50 years, Mary. His death was caused from complications associated with Parkinson’s disease. He was 85. News of his passing reached us just three days ago, which explains why this “etymological” tribute is so late.

Dr. Nafpaktitis was best known for his work on the taxonomy, distribution, ecology and functional morphology of lanternfishes (family Myctophidae) and for his studies of bioluminescence in deep-sea fishes. He is the author or co-author of 22 valid lanternfish taxa, dating from 1966 to 1995.

Only one of the three myctophid names proposed in his honor is still in use. In 1984, Becker and Prut’ko latinized the forename “Basil” to form Diaphus basileusi, described from the northeastern Indian Ocean. The authors honored Nafpaktitis for his important investigations of myctophid systematics, especially of the genus Diaphus. In 1972, Adolf Kotthaus described Lampanyctus basili, a lanternfish from the Seychelles. It is now considered a junior synonym of Lampanyctus macropterus (Brauer 1904). Two years later, Robert L. Wisner proposed the identical name, Lampanyctus basili, for a lanternfish from the South China Sea. Wisner was apparently unaware of Kotthaus’ description, which renders the latter name objectively invalid. Even if the name were not preoccupied, it would today be considered a junior synonym of Lampanyctus turneri (Fowler 1934).

The only other valid fish species named after Nafpaktitis is the Eastern Pacific deep-sea anglerfish Oneirodes basili, described by Theodore W. Pietsch in 1974. Nafpaktitis was Pietsch’s major professor and Chairman of his dissertation committee at the University of Southern California. Pietsch thanked Nafpaktitis for his “guidance, encouragement, enthusiastic support, and friendship.”

It’s interesting to note that all four attempts to name a fish after Nafpaktitis have used his forename instead of his surname.

12 August 2015

Names so offensive, they were pulled from publication

In 1857, Polish-German naturalist William (or Wilhelm) Blandowski (1822-1878) described (or at least named) eight new species of fishes from the Lower Murray River of Australia. The pages were typeset and printed and were about to appear in Transactions of the Philosophical Institute of Victoria. But two of Blandowski’s names offended members of the Institute and the entire fish section of his paper was physically pulled from the publication before it was released.

Blandowski named the Silver Perch, Cernua eadesii, after Richard Eades (1809-1867), a physician at Melbourne Hospital and a co-founder of the Philosophical Institute. Blandowski said the fish was “easily recognized by its low forehead, big belly and sharp spine.”

Blandowski also described the River Blackfish, Brosmius bleasdalii. He named it after the Revd. Dr. John Ignatius Bleasdale (1822-1884), who later became president of the Royal Society of Victoria. “A slippery fish,” Blandowski wrote. “Lives in the mud.”

Eades and Bleasdale took umbrage with these less-than-flattering descriptions. Institute officials accused Blandowski of deliberately lampooning or besmirching the reputations of two well-respected colleagues, pointing to the fact that Blandowski had a motive — simmering disagreements and financial tensions between he and the Institute. They asked Blandowski to change the names or revise the descriptions. Blandowski refused. So the Institute literally yanked the entire fish section from Blandowski’s paper on the “Natural History of the Lower Murray” after it was printed but before it was released. Inserted in its place was a short note:

“Pages 131 to 134 inclusive, with four Plates, are omitted from this volume of the Transactions, by an order of the Council, of date, 7th April, 1858.”

As it turns out, both offending names are junior synonyms of previously described species. Cernua eadesii is actually Bidyanus bidyanus (Terapontidae), described by Mitchell in 1838. And Brosmius bleasdalii is Gadopsis marmoratus (Percichthyidae), whose name dates to Richardson 1848. But Blandowski described seven other species for the very first time. Had he agreed to change the names (or descriptions) of eadesii and bleasdalii, the taxonomic portion of his paper would likely have been published, and Blandowski’s authority would now forever be associated with these species:

Ambassis agassizi Steindachner 1867 = Cernua wilkiensis

Nemataloso erebi Günther 1868 = Megalope caillentassart

Galaxias rostratus Klunzinger 1872 = Uteranka irvingii

Morgurnda adspersa Castelnau 1878 = Kurrina macadamia

Melatotaenia fluviatilis Castelnau 1878 = Jerrina dobreensis

Retropinna semoni Weber 1895 = Turruitja achenson

Craterocephalus fulvus Ivantsoff, Crowley & Allen 1987 = Kohna mackennae

Amazingly, it took 130 years to complete the taxonomy that was redacted from Blandowski’s paper.

Blandowski returned to Europe in 1859, where he tried to get his Australian research published, but to no avail. Quickly, however, he found success in the nascent art of photography. He opened a portrait studio, photographed the local gentry, and documented Prussian life as a 19th-century equivalent of a photojournalist. He never married and died at a psychiatric hospital in Poland.

A number of scholarly articles have reassessed Blandowski’s reputation and ichthyological contributions. They are fascinating to read. Here is one of them.

In addition, two fish genera have been named in his honor: Blandowskius Whitley 1931 (Monocanthidae) and Blandowskiella Iredale & Whitley 1932 (Ambassidae). But, continuing the theme of obscurity that plagued his career, both names have since been subsumed into synonymy.

Apparently, at least one hard copy of Blandowski’s fish descriptions have survived. If you access the Biodiversity Heritage Library’s PDF of the Transactions of the Philosophical Institute of Victoria for 1858, you’ll see that the deleted pages have been reinstated.

The original tipped-in note indicating that the pages had been removed is there as well.

5 August 2015

Corydoras narcissus Nijssen & Isbrücker 1980

One can almost imagine the smirk on Nijssen’s and Isbrücker’s faces when they coined the name of this catfish.

In Greek mythology, Narcissus was a hunter known for his beauty. One day, he saw his own reflection in a pool of water and fell in love with it, not realizing it was merely an image. Unable to leave the beauty of his reflection, Narcissus drowned. Narcissus is the origin of the term narcissism, a fixation with oneself and one’s physical appearance.

The selection of this epithet, the authors say, honors “those who recently collected undescribed Corydoras species and kindly suggested new names for them.”

The collecting party included pet-book publisher and tropical-fish tycoon Herbert R. Axelrod, ornamental-fish wholesaler and supplier Heiko Bleher, and ichthyologist Jacques Géry. The trio also collected Corydoras robustus, described in the same paper.

As far as we know, Nijssen and Isbrücker have never publicly revealed which of the trio for whom they secretly named the catfish. Our money is on Axelrod. Anybody who has read his books and articles or heard him speak at an aquarium show can get the sense that the man thinks very highly of himself. And then there’s the case of the Cardinal Tetra, Paracheirodon axelrodi, which could have been named Paracheirodon cardinalis if Axelrod hadn’t rushed a preliminary description into print.

But that’s a story for a future Name of the Week.

29 July 2015

Two recent “celestial” names

As NASA’s New Horizons was sending back dazzling images of Pluto, we were perusing the descriptions of several new freshwater species from Asia — two of them with names inspired by humanity’s shared fascination with astronomy and beautiful distant objects decorating the night sky.

Homatula change — In the journal Ichthyological Exploration of Freshwaters, Marco Endruweit described this new nemacheilid loach from the upper Black River basin in Yunnan, China. It is named after Chang E (or Chang’e, Chang-o, Heng’e), the goddess of the moon. According to Chinese mythology, Chang E is incredibly beautiful. Endruweit’s choice of the name presumably reflects his opinion of this loach’s coloration in life.

Badis soraya — In the journal Zootaxa, Stefani Valdesalici and Stefan van der Voort describe four new species of the Indo-Burmese genus Badis from West Bengal, India. One of them, B. soraya, is named for the ancient Persian word for The Pleiades, an open cluster of bright blue stars and part of the constellation Taurus. The name refers to the blue blotch covering part of the cleithrum above the pectoral-fin base, and part of the postorbital stripe and blotches on the dorsal-fin sheath, which are often a bright blue.

Biologists have found nomenclatural inspiration from the heavens since the beginning of zoological nomenclature. (Linnaeus, for example, named the cat shark Scyliorhinus stellaris for the many star-like black-and-white spots on its body in 1758.) What’s nice about these two names is that the authors were inspired by other disciplines — mythology and ancient languages — as well.

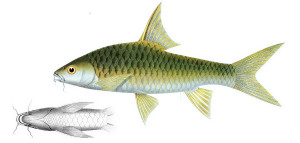

Neolissochilus soro. From: Oijen, M.J.P. van and G.M.P. Loots. 2012. An illustrated translation of Bleeker’s Fishes of the Indian Archipelago Part II Cyprini. Zoologische Mededelingen (Leiden) 86 (1), 8.vi.2012: 1-469, figs 1-131.

22 July 2015

A “soro” state of affairs: Neolissochilus soro (Valenciennes 1842)

At The ETYFish Project, part of your job is keeping our database up-to-date. So we are always tracking the current literature for new species descriptions, name changes, resurrected names, and names sunk into synonymy. In May, Zootaxa published a paper, “Cyprinid fishes of the genus Neolissochilus in Peninsular Malaysia,” in which the authors presented evidence that two species — Lissochilus tweediei and Tor soro — are junior synonyms of Neolissochilus soroides.

Something jumped out at us as being not quite right — the fact that a species named soroides, which means “like soro,” was the senior synonym of the species it was being compared to!

We looked a little deeper and discovered that the authors made a mistake. They assigned the authorship of N. soro to “Bishop 1973,” which would indeed give N. soroides, which was described in 1904, nomenclatural priority if the two taxa were deemed to be conspecific. But Bishop did not describe N. soro in 1973. That name, in fact, dates to Barbus soro, described by Valenciennes in 1842.

We alerted the paper’s editor, Larry Page, regarding the error and he invited us to write a correction. That correction appeared a few days ago, also in the journal Zootaxa. This is the first time that The ETYFish Project has published its own peer-reviewed paper.

(The full paper is password-protected, but you will see 100% of the main text in the open-access abstract. If you would like the complete PDF, let us know.)

Our conclusion is that since “Tor soro Bishop 1973” is not a valid name/author combination, Neolissochilus soro cannot be considered a junior synonym of N. soroides.

Soro, by the way, is local name for this species in Java, Indonesia.

Carapus sluiteri, as found and preserved in host. From: Markle, D. F. and J. E. Olney. 1990. Systematics of the pearlfishes (Pisces: Carapidae). Bulletin of Marine Science v. 47 (no. 2): 269-410.

15 July 2015

Carapus sluiteri (Weber 1913)

One of the rarest fishes in the world was discovered only because a zoologist looked inside the body of another creature.

Carel Philip Sluiter (1854-1933) specialized in tunicates, sipunculids, echiurans and echinoderms. He was part of the Siboga Expedition, a Dutch zoological and hydrographic expedition to Indonesia from March 1899 to February 1900. The leader of the expedition was ichthyologist Max Carl Wilhelm Weber (1852-1937).

Among the many specimens that Sluiter examined was Polycarpa aurata, also known as the Ox Heart Ascidian, the Gold-mouth Sea Squirt or the Ink-spot Sea Squirt. Inside the tunicate was the only known specimen of a pearlfish (family Carapidae). Sluiter showed the fish to Weber, who named it in Sluiter’s honor.

Many species of pearlfish live inside invertebrates, including clams and starfishes in addition to tunicates. Some species are commensal and do not harm their invertebrate hosts. Other species are parasitic, however, as the title of this online article so graphically illustrates:

Absurd Creature of the Week: This Fish Swims Up a Sea Cucumber’s Butt and Eats Its Gonads

The provenance of the generic name Carapus is worth noting, too. It’s an unusual instance of a group of marine fishes bearing the local Brazilian name of fishes from the Amazon. Rafinesque proposed the name in 1810, reflecting the belief at the time that pearlfishes were related to the neotropical knifefish genus Gymnotus. (The two groups of fishes are indeed similar in appearance.) Carapo is the Brazilian name for knifefishes (e.g., Gymnotus carapo Linnaeus 1758, the Banded Knifefish). Carapus is a latinization of Carapo.

Sturisoma festivum, from: Myers, G. S. 1942. Studies on South American fresh-water fishes. I. Stanford Ichthyological Bulletin v. 2 (no. 4): 89-114.

8 July 2015

Our 15,000th name: Sturisoma festivum Myers 1942

2/7/16 UPDATE: According to a new molecular phylogeny of the subfamily Loricariinae, this species has been reassigned to the genus Sturisomatichthys, where it is now known as Sturisomatichthys festivus (Myers 1942).

Last week we reached a milestone, of sorts—the 15,000th entry in our database. And, befitting the occasion, it’s a rather “festive” name.

Stanford ichthyologist George S. Myers described this armored or suckermouth catfish from the Lake Maracaibo basin of Venezuela in 1942. The specific epithet means pleasing or handsome. Myers did not explicitly state why he selected the name, but one look at the illustration and one can guess that Myers was referring to the catfish’s greatly prolonged fins. In addition, Myers notes that young specimens are “very prettily marked.”

The generic name was coined by English zoologist William John Swainson (1789-1855) in 1838. It’s a combination of the Latin words sturio, meaning sturgeon, and soma, meaning body, and likely refers to the sturgeon-like appearance of the genus’ type species, Sturisoma rostratum, particularly its produced snout.

The genus Sturisoma is not yet posted on this site. We hope to release the first of two parts covering the diverse catfish family Loricariidae by the end of July.

The 15,000 name total includes initial work on several orders we will begin to complete just as soon as we finish the catfishes. They include Gymotiformes (South American knifefishes), Esociformes (pikes and mudminnows), Osmeriformes (smelts and allies), Salmoniformes (salmon, trout and whitefishes), and the deep-sea order Stomiiformes.

Our progress has benefited enormously from dozens of scientists and fish enthusiasts — and a few befuddled but patient librarians — but there is a core of people we’ve turned to time and time again for help, translations, knowledge and advice, and they’ve never let us down. They include: Jose Birindelli, Bill Eschmeyer, Ron Fricke, Jan Jeffrey Hoover, Thomas O. Litz, Heok Hee Ng, Larry Page, Mark Henry Sabaj Perez, Artem Prokofiev, Erwin Schraml, Peter Unmack, and Laura Wilson. Thank you all.

15,000 down. Only 25,000 left to go!

1 July 2015

Silver Carp, Hypophthalmichthys molitrix and Bighead Carp, H. nobilis

Our very good friend Jan Jeffrey Hoover is a fish ecologist with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ Engineer Research and Development Center in Vicksburg, Mississippi. He recently uploaded a video about his work testing the swimming ability of Asian carps — specifically, the two species named above — using a mobile swim tank to learn whether flows from locks and dams on the Mississippi River can be used to help keep these non-native, invasive fishes out of the upper Mississippi and the Great Lakes. It’s a fascinating look at some fascinating research about a serious ecological threat.

Both Silver Carp and Bighead Carp are filter feeders, using extremely close-set gill rakers to remove plankton, algae, and detritus from the water. It’s this feeding strategy that attracted commercial Arkansas fish farmers, who first imported the carps from Asia to America in the early 1970s. Since catfish culture ponds often suffer from a cloudy build-up of nutrients and waste products, the fish farmers stocked the carps to filter the ponds and improve their catfish-yielding capacity. Although subsequent studies have not confirmed whether Bighead and Silver Carp can actually perform this task, the species were cultured in various hatcheries anyway and distributed to private fish farms and municipal sewage lagoons in Arkansas and throughout the Midwest. By 1980, the two carps began to appear in open waters as a result of escapes from hatcheries and aquaculture facilities, and intentional (illegal) stocking. The Silver Carp has been reported from 12 states and is established in Louisiana and probably also in Illinois. The Bighead Carp is known to occur within or along the borders of 18 states and is established in Illinois and Missouri. The spread of reproducing Silver and Bighead Carps to additional states is inevitable.

The impact of these species is difficult to predict because of their place in the food chain. Because of their large size—Silver Carp can reach 27 kg (60 lb), bighead carp 40 kg (88 lb)—these fish have the potential to deplete zooplankton populations and thereby wipe out the base of the food web that supports native filter feeders such as Paddlefish (Polyodon spathula), Bigmouth Buffalo (Ictiobus cyprinellus), Gizzard Shad (Dorosoma petenense), the larval young of other fishes, and freshwater mussels.

The imminent spread of Asian carp into the Great Lakes basin is a major worry. The fish breeds prolifically (Australian biologists call them “river rabbits”), and many fear they could overrun the Great Lakes and turn them into a giant “carp pond.”

Of course, their names, coined in the 19th century, reflect none of the ecological worries these two species now represent. The generic name Hypophthalmichthys, proposed by Bleeker in 1860, translates as hypo-, under, ophthalmus, eye, and ichthys, fish, and refers to their downward-looking ventrolateral eyes.

Molitrix means miller or grinder, but Valenciennes did not mention the origin of the name in his very brief description of Leuciscus molitrix in 1844. Nor did Valenciennes mention the fish’s teeth. Nevertheless, most ichthyologists believe the name refers to the Silver Carp’s pharyngeal teeth, which it uses to grind phytoplankton.

The specific epithet of H. nobilis has an interesting provenance. It doesn’t mean “noble,” as some references indicate. Instead, it means “well known.” Proposed by Richardson in 1845, the name appears to reflect the phrase “Eminent fish,” which is an English translation of its Chinese vernacular (phonetically spelled Tsing yu). Richardson learned about Tsing yu from John Reeves, who painted the species while working as a tea inspector in China from 1812 to 1831.

Ironically, H. nobilis continues to be a well-known fish to this day, but for all the wrong reasons.

24 June 2015

24 June 2015

Hypoptopoma baileyi Aquino & Schaefer 2010

This loricariid catfish occurs in the Upper Madeira basin of Brazil. According to the authors:

“The specific epithet baileyi is a patronym honoring Reeve M. Bailey (1911–2000), who collected the specimens of the new species in 1964 during an expedition of the AMNH [American Museum of Natural History] to the Río Itenez.”

One small problem: Reeve M. Bailey did not die in 2000. In fact, was still alive in 2010 when this catfish’s description was published.

The Emeritus Curator of Fishes at the Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan, passed away 2 July 2011 at the age of 100.

17 June 2015

Osmerus eperlanus schonfoldi McAllister 1984

We like the subspecific epithet schonfoldi because it is so obscure. Very few reference works include it, and the identity of the person it honors was fun to figure out. This is probably the first time anyone’s ever contemplated the person behind the name since it was proposed in 1772.

Today, the name officially dates to a chapter on smelts written by Canadian ichthyologist Donald Evan McAllister (1934-2001) in the 1984 multi-authored multi-volume work Fishes of the North-eastern Atlantic and the Mediterranean. McAllister listed the smelt, which occurs in fresh, brackish and marine waters of Poland westward to the British Isles, as a valid subspecies of the European Smelt, Osmerus eperlanus (Linnaeus 1758).

McCallister credited the name to Eperlanus schonfoldii, published by an Irish Quaker physician-naturalist named John Rutty (1697-1775) in 1772. The full title of the privately published work is An essay towards a natural history of the county of Dublin, accommodated to the noble designs of the Dublin Society; affording a summary view.

“The ensuing Catalogue of Fishes,” Rutty wrote, “exhibits all those that I have been informed of that are either caught here [in Dublin], or brought to our Market, a Market abounding with great plenty and variety of Fishes, and much exceeding that of London in plenty and cheapness.”

One of these fishes Rutty called The Smelt, “Eperlanus Schonfoldii.” His complete description reads: “It is frequent in July and August, the flesh soft, tender and of a delicate flavour.”

Since Rutty did not include any distinguishing characteristics in his description, the name is a nomen nudum and not valid for nomenclatural purposes. McAllister seemed unaware of this when he resurrected the name in 1984. Since his account of the subspecies distinguished it from the nominate form Osmerus eperlanus, he became, by rule, the author of the name.

“Eperlanus” appears to be a latinization of the Old French éperlan, of Teutonic origin, a vernacular name applied to small edible fishes that migrate to fresh water to spawn, now colloquially known as smelt (an interesting etymological story in itself, best saved for a future Name of the Week). But who was Schonfold? Why did Rutty honor him with the name? Rutty didn’t say, but he offered a clue. In his brief write-up on dolphins, Rutty wrote “Phocena quam Schonfeldus Delphinus Septentrionalium vocat.” Or, “Phocena is what Schonfeld calls the Northern Dolphin.”

So, assuming that “Schonfeld” and “Schonfold” are the same person, it appears that Rutty named his smelt after someone who had written some kind of treatise on marine life. At first, our Google searches for both spellings of the name came up zero. Then we found a bibliographical web site with an entry for one Stephan Schonevelde, who wrote a 1624 volume called Ichtyologia et nomenclaturae animalium marinorum, fluviatilium, lacustrium quae in florentissimis ducatibus Slesvici et Holsatiae & celeberrimo Emporio Hamburgo occurunt triviales. His name was spelled several ways, including Schonefeld, Schone Velde and Schoenfeld. We believe we can add Schonfeld and Schonfold to the list.

Not much is known about Schonevelde. He was born in Hamburg in the middle of the 16th century, studied medicine, and served as personal physician to the Duke Johann Adolf von Schleswig-Holstein. Like many physicians of the time period, he also was a naturalist, most interested in the natural history of the North and Baltic Sea and the fishes of Elbe River of Central Europe. He is regarded as one of the first ichthyologists of Germany and one of the most famous naturalists of his time. No one is sure when he died.

Our guess is that Rutter relied on Schonevelde’s work in writing his natural history of Dublin, and honored the German naturalist by naming the smelt after him.

And that is how a 20th-century Canadian ichthyologist inadvertently became the author of a smelt subspecies named by an 18th-century Irish naturalist in honor of a German naturalist who lived a century-and-a-half before.

10 June 2015

Lethenteron reissneri (Dybowski 1869)

As far as we know, this is the first time that The ETYFish Project has been cited in a peer-reviewed journal: Renaud, C. B. and A. M. Naseka. 2015. Redescription of the Far Eastern brook lamprey Lethenteron reissneri (Dybowski, 1869) (Petromyzontidae). ZooKeys 506: 75-93.

Lethenteron reissneri (Dybowski 1869) ANSP 185410 (live), SL ca. 140 mm. MON 06-06, Barh River (Onon-Amur Dr.). Photo by Mark Sabaj Pérez, The Academy of Natural Sciences.

L. reissneri is a nonparasitic lamprey that occurs in the Shilka (Russia and Mongolia) and Songhua (People’s Republic of China) river systems within the Amur River basin. It was described as Petromyzon reissneri by the Polish naturalist and physician Benedykt Dybowski (1833-1930).

According to Renaud and Naseka, “Dybowski (1869) did not specify [the etymology of the name], but this species was possibly named after Baltic German anatomist Ernst Reissner (1824–1878), as suggested by Scharpf and Lazara (2013).”

Hey, glad to have helped!

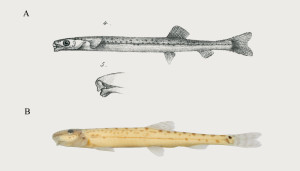

Top: Aperioptus pictorius, reproduced from Richardson (1848). Bottom: specimen collected from Way Ketimbung, Lampung Province, Sumatra, 30 July 2006. Courtesy: L. M. Page.

3 June 2015

Aperioptus pictorius Richardson 1848

Late last year, Larry Page, Curator of Fishes at the Florida Museum of Natural History, emailed us saying that The ETYFish Project did not have an entry for the above-named loach in our database. We explained that we did not include the name because it was a presumed junior synonym of the cobitid loach Acantopsis dialuzonas van Hasselt 1823.

Now Dr. Page, along with Weerapongse Tangjitjaroen of Chiang Mai University (Thailand), have resurrected both the generic and specific names, in a recent issue of the journal Zootaxa. In so doing, Aperioptus replaces the genus Acanthopsoides, proposed by Fowler in 1934, and A. pictorius replaces species Acanthopsoides molobrion, described by Siebert in 1991.

The etymology of this loach’s name, and the reason it’s been overlooked by taxonomists for 167 years, are actually the same story.

Scottish naval surgeon and naturalist John Richardson (1787-1865) described the species in 1848. But he didn’t have much to describe.

Of this fish I can give no details. There were two specimens which I unfortunately placed in the hands of the artist before I had examined them, except very cursorily. While he was employed in sketching, he put them into a plateful of water for the purpose of expanding their fins more perfectly, and forgetting that he had not returned them into the spirits, they were thrown out and lost. The general aspect of the fish is that of a slender Galaxias, but there are no teeth on the jaws. The orifice of the mouth is a narrow vertical oval, which is restricted on the sides by membranous processes.

Richardson did not explain the selection of the name “Aperioptus pictorius,” but it no doubt reflects his having only an illustration from which to work. “Aperio” means to uncover, expose, open, or reveal. “Optus” means seen or visible. “Pictorius,” an adjective, means pictorial or belonging to painters. In other words, the existence of this species has been revealed by means of a picture.

And, by virtue of this very same picture, the identity of species has also been revealed, 167 years after it was named.

27 May 2015

Lampris guttatus (Brünnich 1788)

The Opah, or Moonfish, has been in the headlines recently, with the recent revelation that it is the world’s first-known fully warm-blooded, or endothermic, fish. This, of course, got us curious about the fish’s names — both scientific and vernacular.

The specific epithetic guttatus dates to a 1788 publication by the Danish zoologist and mineralogist Morten Thrane Brünnich (1737-1827). “Guttatus” means spotted and clearly refers to the many white spots that cover its flanks. Brünnich originally named the species Zeus guttatus, placing it in the genus that is now restricted to the unrelated dories of the family Zeidae. The name Zeus, while officially dating to Linnaeus 1758 (the official starting point of zoological nomenclature), was not coined by Linnaeus. He simply provided the name for the John Dory (Zeus faber) provided by Pliny the Elder. What prompted Pliny to name this fish after the “Father of Gods and men” is not clear.

The Swedish chemist-biologist Anders Jahan Retzius (1742-1821) created a new genus for the Opah, Lampris, in 1799. That name is from the Greek lamprós, meaning radiant, brilliant or shining, and no doubt refers to the Opah’s brilliant coloration.

The derivation of the common name Opah is not so clearly known. In 1903, Smithsonian ichthyologist (and fish-name etymologist) Theodore Gill reported that the name’s first appearance in print (with an explanation) was in 1750, in a paper published in the venerable science journal, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, under the title “The Description of a Fish, Shewed to the Royal Society by Mr. Bigland, on March 22, 1749-50: Drawn up by C. Mortimer, M. D. Secret. R. S.”

According to the authors, who described and illustrated what was clearly Lampris guttatus 38 years before Brünnich’s description, Opah is the native name for this species off the coast of Guinea, where their specimen was caught.

Gill was skeptical of this claim, noting that the Opah had never been recorded from the western coast of tropical Africa. But we now know that the pelagic Opah is a circumglobal fish whose range in the eastern Atlantic extends well past Guinea to the south of Angola. Therefore, there is no reason to doubt the 1750 claim that the word Opah is derived from a native Guinean name.

20 May 2015

20 May 2015

Dactyloscopus poeyi Gill 1861

This week we celebrate the 216th birthday of the Cuban ichthyologist Felipe Poey. Born on May 26, 1799, to French and Spanish parents in Havana, Poey moved with his family to France when he was five, where he developed his lifelong appreciation for the natural world. Schooled as a lawyer, he traveled back and forth between Cuba and Spain, ultimately leaving Spain — and law — for settling in Cuba for good in 1833. There he became the country’s most eminent zoologist, at first studying butterflies and then increasing his focus on fishes.