NAMES OF THE WEEK from: 2013 2014 2015 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 2023 2024 2025

Smallscale Pacú, Piaractus mesopotamicus. From: Auburn University, School of Fisheries, Aquaculture and Aquatic Sciences, Media Gallery.

28 December 2016

Piaractus mesopotamicus (Holmberg 1887)

Sometimes we need to guess at the etymology of a name. We hope that we guess right most of the time. In this case, we guessed wrong. Fortunately, a sharp-eyed reader has corrected us.

In 1887, Argentine biologist (and science-fiction novelist) Eduardo Ladislao Holmberg (1852-1937) described a new species of Pacú (Serrasalmidae) from Rio Paraná of Uruguay. He named it Myletes (now Piaractus) mesopotamicus but did not explain the name.

We scratched our heads. Why did Holmberg name a fish from Uruguay after Mesopotamia (“[land] between rivers”), the Ancient Greek name for the Tigris-Euphrates river system of Iraq, Kuwait, Syria and Turkey? We decided that Holmberg was using the term in a different way and proposed this explanation:

–icus, belonging to: meso-, middle; potamos, river, allusion not explained nor evident, perhaps referring to occurrence or abundance in middle reaches of Paraguay-Paraná River basin

What we did not realize is that “Mesopotamia” is also used to describe the northeast region of Argentina located between the rivers Paraná and Uruguay, precisely where this Pacú occurs.

Stefan Koerber kindly alerted us to this fact and corrected our explanation. Koerber maintains the site www.pecescriollos.de, an excellent resource on the systematics and distribution of the freshwater fishes of Argentina and Uruguay.

Thank you, Stefan. We dislike being wrong. But we love the fact that there are people like you who take the time to set us straight. We appreciate it.

Here’s to a happy — and error-free — 2017!

Courtesy of Ronald Fricke, from: R. Fricke, et al. 2016. New case of lateral asymmetry in fishes: A new subfamily, genus and species of deep water clingfishes from Papua New Guinea, western Pacific Ocean. Comptes Rendus Biologies (in press).

21 December 2016

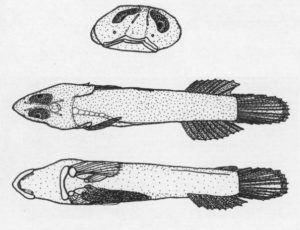

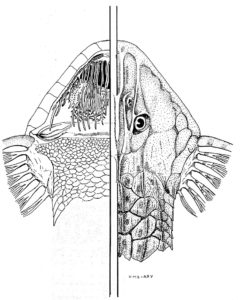

Protogobiesox asymmetricus Fricke, Chen & Chen 2016

External asymmetry in vertebrates is rare. It’s known from a few birds, a few mammals, and, except for the flatfishes (Pleuronectiformes), it’s seldom seen in fishes too. The only example we know about is Perissodus microlepis, a scale-eating cichlid from Lake Tanganyika, in which the mouth is either turned to the right (for eating scales off the left side of its prey) or to the left (for eating scales off the right side of its prey).

Now a new subfamily of clingfishes, Protogobiesocinae (Gobiesocidae), has been proposed, containing two species that exhibit lateral asymmetry: Lepadicyathus mendeleevi Prokofiev 2005 and Protogobiesox asymmetricus, the latter representing both a new genus and species.

True to its specific name, P. asymmetricus exhibits a number of asymmetric features in the male holotype:

- Skull is slightly asymmetrical when seen from the front (top illustration), with an oblique mouth slit and left eye situated lower than right eye

- Vertebral column inserts slightly on the left-hand side of the skull (middle illustration), and then strongly turns left, meeting the left-hand side of the body on the level of the dorsal fin insertion

- Anal fin inserts on right-hand side of body

- Internal organs are restricted to right half of body (bottom illustration); anus is likewise situated on right-hand side.

- Fins and supporting elements on right-hand side and are much smaller than corresponding elements on left-hand side (disc asymmetry

Interestingly, in the female paratype, the asymmetries are the other way around, with the vertebral column turning towards the right-hand side of the fish, and the anus and the internal organs shifted towards the left-hand side.

P. asymmetricus occurs along the north coast of Papua New Guinea, where it was collected at depths of 381–480 m. The name of the new genus derives from protos, meaning first or ancestral, and refers to how the pelvic fins resemble the putative ancestral form of clingfishes (gobiesocids).

Lepadicyathus mendeleevi — also from the north coast of Papua New Guinea — is redescribed, with its asymmetry being noted for the first time. Artém Prokofiev, who described the species, apparently was not aware of its asymmetry. However, he did note that the paratype was artificially “crumpled.” Its generic name refers to its external similarity to the genus Lepadichthys Waite 1904 (Lepa-), but with two (di-) instead of one sucking disc (cyathus, cup or bowl). The specific name honors the research vessel Dmitrii Mendeleev, from which the type was collected. The vessel itself is named for the Russian chemist Dmitrii Mendeleev (1834-1907), who published the first widely recognized Periodic Table of Elements in 1869.

14 December 2016

The 2016 “Fish of the Year” is our Name of the Week

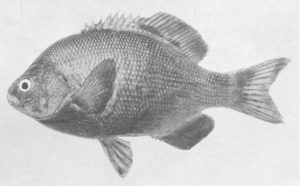

Pagellus acarne (Risso 1827), the Axillary Seabream (family Sparidae), occurrs in the Mediterranean Sea and the eastern Atlantic from the North Sea to Senegal and the Cape Verde Islands, including Madeira.

Pagellus acarne (Risso 1827), the Axillary Seabream (family Sparidae), occurrs in the Mediterranean Sea and the eastern Atlantic from the North Sea to Senegal and the Cape Verde Islands, including Madeira.

French naturalist Antoine Risso (1777-1845) was the first to give the species a Linnaean name, Pagrus acarne, in 1827. The specific epithet is borrowed from Rondelet’s Libri de piscibus marinis, in quibus veræ piscium effigies expressæ sunt of 1554, who called the fish “De Acarnane” (then spelled “De Acarne” in a later edition). The name connotes that the fish is a resident of Acarnania, a region of west-central Greece that lies along the Ionian Sea, an embayment of the Mediterranean.

The generic name Pagellus dates to Valenciennes 1830. Some references indicate that the name is a diminutive of the original generic name Pagrus, which itself is the Greek word for seabream (and the source of the common name “porgy”). But Valenciennes clearly indicated that he borrowed the name from the words “pagel” and “pageau,” both of which were used by the sailors of Provence and Languedoc, France, for the type species Pagellus erythrinus (Linnaeus 1758). Our guess is that these French vernaculars are also derived from the Greek “Pagrus.”

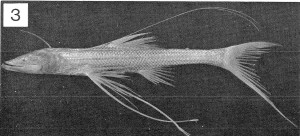

From: Gilbert, C. H. and C. L. Hubbs. 1916. Report on the Japanese macrouroid fishes collected by the United States Fisheries steamer “Albatross” in 1906, with a synopsis of the genera. Proceedings of the United States National Museum v. 51 (no. 2149): 135-214, Pls. 8-11.

7 December 2016

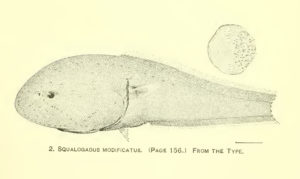

Squalogadus modificatus Gilbert & Hubbs 1916

Sometimes when we can’t figure out the meaning of a name, we seek expert help.

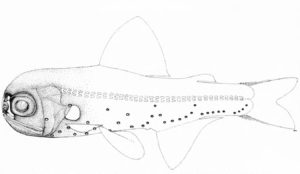

Squalogadus modificatus, the Tadpole Whiptail (Order Gadiformes, Family Trachyrincidae) occurs in the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans at depths of 600 to 1,740 meters (1,970 to 5,710 ft). It grows to a total length of 35 cm (14 in). It is the only known member of its genus.

Charles Henry Gilbert and Carl H. Hubbs proposed both the genus and the species in their 1916 paper on the macrouroid fishes of Japan. They did not explain the meaning of the specific epithet modifacatus, but we’re pretty sure it means “modified.” They did, however, explain the meaning of the generic name: “Squalus, a shark; Gadus, the cod.” But try as we might, we failed to see anything shark-like about this tadpole-shaped fish. What the heck were Gilbert and Hubbs referring to?

So we brought in Tomio Iwamoto, Curator Emeritus of Ichthyology, California Academy of Sciences, and a worldwide expert on the taxonomy of grenadiers (Family Macrouridae, in which S. modificatus had originally belonged), as our expert consultant.

Dr. Iwamoto said the squalus (shark) part of the name may refer to its prickly scales, which resemble the denticulate skin surfaces of most sharks. (Gilbert and Hubbs said the scales were “small, covered with spinules.” They also illustrated a scale, as shown above.)

The specific epithet modifcatus, Dr. Iwamoto explained, possibly refers to its huge bulbous head, which appears to be an extreme example of morphological change (i.e., modified) from a basically cod-like body plan.

30 November 2016

Curimata mivartii Steindachner 1878

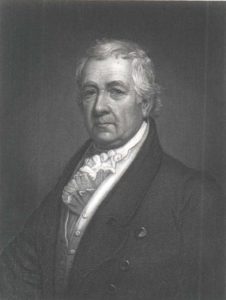

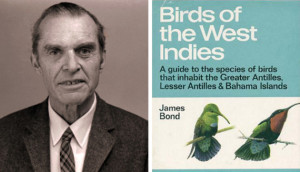

St. George Jackson Mivart (date unknown). Photograph by Barraud & Jerrard. Courtesy: Wellcome Images.

Austrian ichthyologist Franz Steindachner often named fishes in honor of colleagues and scientific leaders of his day. He usually didn’t identify the subjects of his patronyms. We’re not sure why. Perhaps the honorees were so well-known among the scientific cognoscenti that calling them out was considered gratuitous or impolite. Curimata mivartii, a toothless characin (Curimatidae) from the Río Magdalena of Colombia, is one such name. Unless there were two Mivarts toiling in the world of science at the time, we’re pretty sure the name honors British zoologist St. George Jackson Mivart (1827-1900). In fact, today, 30 November, is the 189th anniversary of his birth.

Largely forgotten today, Mivart was a complex, conflicted man. He harshly criticized Darwin’s theory of evolution. And, as a Roman Catholic, he believed in biblical creation, but had his own theory on how species came to be. (Basically, variation was predetermined by a higher intelligence.) Mivart attempted to debunk Darwin’s Origin of Species (1859) with his own Genesis of Species (1871). The debate got intense at times. Darwin kept his cool. Mivart did not. His reputation suffered.

While making an enemy of Charles Darwin, Mivart also managed to make enemies within the Catholic Church. His attempts to reconcile Darwinism with Catholicism were considered heresy. Mivart was excommunicated a few months before he died of diabetes in 1900. His remains were not allowed to be buried in consecrated ground until 1904.

We don’t know why Steindachner honored Mivart. Nor do we know whether Steindachner took sides in the Darwin-Mivart debate. But we do know that Steindachner named a flounder — Oncopterus darwinii (Pleuronectidae) — after Darwin four years earlier, in 1874. In this case, Steindachner had an explicit reason for honoring the great naturalist: Darwin described a similar if not identical flounder in his journal notes during the historic second voyage of HMS Beagle (1831-1836).

![Rhinoraja odai holotype (adult male), sub-adult female, and egg case (scale 5 cm). From: Ishiyama, R. 1958. Studies on the rajid fishes (Rajidae) found in the waters around Japan. Journal of the Shimonoseki College of Fisheries v. 7 (nos 2-3): 191-394 [1-202], Pls. 1-3.](https://etyfish.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Rhinoraja-odai-270x300.jpg)

Rhinoraja odai holotype (adult male), sub-adult female, and egg case (scale 5 cm). From: Ishiyama, R. 1958. Studies on the rajid fishes (Rajidae) found in the waters around Japan. Journal of the Shimonoseki College of Fisheries v. 7 (nos 2-3): 191-394 [1-202], Pls. 1-3.

Rhinoraja odai Ishiyama 1958

Many times we’ve revealed how the scientific names of fishes have been mistranslated or misinterpreted, leading to incorrect or misleading etymological explanations. While we’d like to think that our explanations are definitively correct, we’re not immune to slipping up ourselves.

This is how we initially reported the etymology of the specific name of Rhinoraja odai, a skate from the Western North Pacific of Japan: “latinization of Japanese vernacular, Oda-ei.”

Indeed, Oda-ei is the Japanese name for this ray. Ishiyama said so in his description. –jei (and its cognate –ei) mean “skate or ray” and forms the names of several Japanese batoid taxa, e.g., Okamejei kenojei (Müller & Henle 1841), Myliobatis tobijei Bleeker 1854, Aetobatus narutobiei White, Yamaguchi & Furumitsu 2013. Since Ishiyama provided no other information about the name, we assumed “oda” was a Japanese word, perhaps of local provenance, meaning unknown.

We consulted the description of Rhinoraja odai in the library, standing in the stacks, turning to the specific pages (347-350) in which the ray was described. Recently, we received a PDF of Ishiyama’s monograph, all 202 pages of it. While perusing the acknowledgments section (page 195), we saw that Ishiyama thanked someone name Mikiji Oda, who supplied a fish that he procured at a fish market off the Izu Peninsula, Shizuoka Prefecture, Aichi Province, Japan. We checked the type locality of R. odai and it matched perfectly. “Oda-ei” means “Oda’s Ray” and “odai” is not a latinization of a Japanese name but a patronym.

Unfortunately, we know nothing about Mikiji Oda. Was he a scientist? A fisherman? An amateur naturalist? We’ll keep searching.

We regret the error but celebrate the correction. We’re glad Mikiji Oda—whoever he might have been—is getting the etymological credit he deserves.

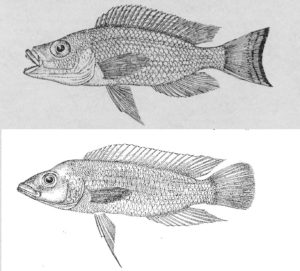

Top: Neolamprologus leloupi, from Poll, M. 1948. Descriptions de Cichlidae nouveaux recueillis par la mission hydrobiologique belge au Lac Tanganika (1946-1947). Bulletin du Musée Royal d’Histoire Naturelle de Belgique v. 24 (no. 26): 1-31.

Bottom: Neolamprologus leleupi, from Poll, M. 1956. Poissons Cichlidae. Exploration Hydrobiologique du Lac Tanganika (1946-1947). Résultats scientifiques. v. 3 (fasc. 5 B): 1-619, 10 Pls.

16 November 2016

Two cichlids, same lake, one letter apart

Here’s a nomenclatural curiosity that at first glance seems like a typo but isn’t.

In 1948, Belgian ichthyologist Max Poll described a new cichlid species from Africa’s Lake Tanganyika: Lamprologus (now Neolamprologus) leloupi.

Twelve years later, Poll described another new cichlid species from Lake Tanganyika. He named it Lamprologus (now Neolamprologus) leleupi.

Neolamprologus leleupi vs. Neolamprologus leloupi. Both from Lake Tanganyika. See the potential for confusion?

N. leloupi was named in honor of malacologist Eugène Leloup (1902-1981). He served as mission chief of the Belgian expedition (1946-1947) to Lake Tanganyika, during which type was collected.

N. leleupi was named in honor of entomologist Narcisse Leleup (1912-2001), who collected the holotype in addition to many other Tanganyikan cichlids described by Poll in the same publication.

Do you think Poll was aware of the one-letter difference in the names?

From: McCosker, J. E. and R. J. Lavenberg. 2001. Gordiichthys combibus, a new species of eastern Pacific sand-eel (Anguilliformes: Ophichthidae). Revista de Biología Tropical v. 49 (Suppl. 1): 7-12.

9 November 2016

Gordiichthys combibus McCosker & Lavenberg 2001

Last week’s alcohol-themed names reminded us of another name that relates to drinking. This time, though, we have some inside information about the name that was not included in the original description.

Gordiichthys combibus is a sand-eel known to occur over gray-colored sand in shallow waters along the Pacific coast of Columbia. It is very similar to G. randalli — named for ichthyologist John E. Randall (Bishop Museum, Honolulu), who collected the type in the Atlantic waters of Puerto Rico.

The similarity of these two species inspired the specific epithet: combibe, to drink with a companion, referring to the sibling nature of this eastern Pacific species to its Atlantic congener G. randalli.

Knowing that John (“Jack”) Randall and John E. McCosker are frequent collaborators and dive buddies, we asked Dr. McCosker: Do you combibe with Jack Randall and, if so, was that a private inspiration the name?

Here, for the etymological record, is McCosker’s reply:

“Yup.”

The etymology of the generic name Gordiichthys also is worth mentioning. Coined by David Starr Jordan and his student Bradley Moore Davis (later a botanist) in 1891, the name is taken from the horsehair worm genus Gordius, which itself is named after the ancient Greek king whose complicated (“Gordian”) knot was cut by Alexander. The name refers to the eel’s thin, elongate body.

2 November 2016

2 November 2016

Two guys getting drunk describing fishes

That’s the image that comes to mind when you read the etymologies of two grenadiers (Gadiformes: Macrouridae) described by Tomio Iwamoto and Nigel R. Merrett in 1997.

Spicomacrurus adelscotti, found in the western Pacific and southeastern Indian oceans off Australia at a depth of ~600 m, is not named after a person. It’s named after a beer. “The name comes from a notably fine French ale,” the authors wrote, “with which we celebrated the discovery of [this] new species.”

One of the authors, it seems, celebrated quite a bit. In the same paper they also described Ventrifossa vinolenta, which occurs in the southwestern Pacific off the Chesterfield Islands of New Caledonia. The name comes from a Latin word meaning “wine-colored” and refers to the overall tint of the trunk and tail of this species. But Iwamoto and Merrett note that the name also means “drunk on wine” — referring to Merrett’s nose!

Cheers!

A male Profundulus punctatus, from La Venta River, Ocozocoautla, Chiapas, México. Photo © Adán E. Gómez González.

26 October 2016

Profundulus Hubbs 1924

Here’s an instance of ichthyologists helpfully including an etymology section in their revalidation and redescription of a species, but, unfortunately, getting half of the etymology wrong.

Earlier this month, a team of eight ichthyologists published a paper in Zootaxa redescribing the Middle American Killifish Profundulus balsanus Ahl 1935, which for many years had been treated as a junior synonym of P. punctatus (Günther 1866). In their “Etymology” section, the authors state that Ahl selected the specific epithet “balsanus” under the mistaken belief that the fish’s type locality in the town of Malinaltepec, Guerrero, México, belonged to a river that drained to the Balsas River. According to the present authors, however, the streams in the town of Malinaltepec all belong to the Papagayo River drainage. Furthermore, no reports of specimens of Profundulus collected in the Rio Balsas River are known to exist.

The authors also explain the etymology of “Profundulus,” saying that it derives from the Latin profundus, meaning deep. They offer no source for this explanation, but our guess is that they consulted the etymology given by FishBase. As any faithful reader of this blog will know, we frequently censure FishBase for getting the etymology wrong.

The authors should have questioned the FishBase etymology right from the start. Does the genus occur in deep water? Hardly. Does it have a deep body? No, it does not. Beyond that, any killifish enthusiast should immediately see that the generic name includes the name Fundulus, a genus of North American killifishes that initially contained the type species of Profundulus, P. punctatus. What’s more, the authors apparently failed to see that pro– is a prefix that means “in front of” or “before.” When combined with an established generic name, the prefix pro– often connotes a taxon that is in some way believed to be “ancestral” compared to related genera (e.g., Proeutropiichthys, Propimelodus).

A check of Hubbs’ 1924 description of Profundulus — a free download courtesy of the University of Michigan — would have confirmed these suppositions. While Hubbs did not explicitly explain the etymology of Profundulus, he did say “it seems not improbable that Profundulus, of all American genera, diverges least from a general ancestral cyprinodont type” (p. 12). While Profundulus and Fundulus are now placed in separate families (Profundulidae and Fundulidae), they were considered confamilials in 1924. To us it seems pretty clear that Hubbs named Profundulus because he believed it was an older, ancestral genus, figuratively “in front of” or “before” Fundulus.

19 October 2016

19 October 2016

HAPPY NATIONAL HAGFISH DAY!

Eptatretus stoutii (Lockington 1878)

Yes, that’s right. October 19 is officially National Hagfish Day, one of those pseudo-holidays created by non-profits and industry trade organizations as a marketing gimmick. National Hagfish Day was created in 2009 by Whaletimes, Inc., an educational non-profit organization that promotes marine science awareness to K-12 students and their teachers.

Hagfishes, of course, are noted for the copious amounts of slime they produce. Which got us wondering: Have any of the 81 species of hagfish been named after a “slimy” (i.e., creepy, oily, unctuous) person? We don’t know if Arthur B. Stout qualifies as slimy, but he certainly held some unpleasant views.

The Pacific Hagfish, Eptatretus stoutii, was described by English zoologist William Neale Lockington (1840-1902) in 1878. Lockington was the curator of the California Academy of Sciences (CAS) museum from 1875 to 1881. He named the hagfish after Arthur B. Stout (?-1898), a surgeon and corresponding secretary of CAS.

Stout was well known in San Francisco for his racist views (back in the days when being a racist was considered a noble and desirable trait). Stout was especially anti-Chinese. In 1862, he published Chinese Immigration and the Physiological Cause of the Decay of the Nation. In it he wrote that China was seeding America with various diseases, including tuberculosis, scrofula, syphilis, and “mental alienation” (whatever that is). He also said that welcoming Chinese (as well as African) people into American society would create a “cancer” in the country’s “biological, social, religious, and political systems.”

“By intermingling with Europeans,” Stout went on, “we are but reproducing our own Caucasian type; by commingling with the Eastern Asiatics, we are creating degenerate hybrids.”

Slime notwithstanding, hagfishes are honorable, fascinating creatures that deserve to be named after less-odious humans than Dr. Stout. We can only hope that he contributed more to the California Academy of Sciences than he did to humankind.

12 October 2016

12 October 2016

Synchiropus sycorax Tea & Gill 2016

Several fish names have been derived from film, literature and popular culture. Star Wars. Batman. The Lord of the Rings. The Hunchback of Notre Dame. The Three Musketeers. The Lorax. The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. The works of Shakespeare.

This stunning new species of dragonet (Callionymidae) from the Philippines adds a new pop-culture reference to our nomenclatural inventory.

According to the authors, Yi-Kai Tea and Anthony Gill, Synchiropus sycorax “is named after the red-robed and caped Sycorax warriors from the BBC sci-fi series Dr. Who, in showing similarities in both coloration and grandiloquence of their garb.”

The generic name Synchiropus — coined by a different Gill, Theodore, not Anthony, in 1859 — represents a combination of the Greek syn-, meaning with or together, cheir, meaning hand, and pous, foot. One online reference says this name refers to how the ventral fins are used as feet. That is wrong, and a perfect example of misinformation that could have been avoided if one had checked the original description. Because Gill clearly explained the name:

“There can be at this day no doubt entertained as to the propriety of forming for the species thus distinguished a distinct genus, and the name of Synchiropus is offered as its generic appellation, a name which alludes to the peculiar connection of the ventrals [via a membrane] to the bases of the pectorals.”

To paraphrase the ninth incarnation of Dr. Who, “Fintastic!”

Zeus the fish, not the fungus. The John Dory, Zeus faber, courtesy Wikipedia.

5 October 2016

When a fish is also a plant or fungus

The International Code of Zoological Nomenclature mandates that no two groups of animals can have the same generic name. The International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants* has the same mandate: no two genera can have the same name. However, these two codes are independent, which means the same generic name can be used for organisms in separate kingdoms. Here are four examples from the world of fishes.

- Zeus Linnaeus 1758 is the type genus of the dory family Zeidae. It’s named for the Greek god Zeus, equivalent to the Roman god Jove or Jupiter, referring to the ancient name of the John Dory, faber,** “Piscis Jovii.” Zeus Minter & Diamandis 1987 is the name of a monotypic fungus discovered on Mount Olympus in Greece. The name also refers to the Greek god Zeus, who made Mount Olympus his home.

- Mallotus Loureiro 1790 is a genus of the spurge family Euphorbiaceae, flowering plants from tropical Africa, Madagascar, Southeast Asia, eastern Australia, and Indian Subcontinent. Its name is from the Greek word for “wooly” or “fleecy,” referring to its villose (shaggy) surface of the plant and/or to its wooly fruits. Mallotus is also the generic name of the Capelin, villosus. Proposed by Cuvier in 1829, it also means fleecy or wooly, referring to a band of elongate scales along lateral line and middle of belly of breeding males, which appear to be hairy.

- Lactarius Persoon 1797 is a genus of mushrooms, commonly called milk-caps, characterized by the milky white fluid they exude when cut or damaged. The name means “producing milk,” i.e., lactating. Valenciennes repurposed the name in 1833 for the False Trevally (L. lactarius), creating a tautonym from the name Scomber lactarius, proposed by Bloch & Schneider in 1801, who note that this species is called “Peixe laite” (“milkfish”) among Portuguese colonizers in India. According to Valenciennes, “milkfish” refers to the “excessive delicacy of its flesh” (translation).

- Knightia Brown 1810 (family Proteaceae) is a genus of plants endemic to New Zealand. It was named for Thomas A. Knight (1759-1838), an English horticulturalist and plant physiologist. In 1907, David Starr Jordan used the same name for an extinct genus of Eocene clupeiform fishes from North America (now famous as the state fossil of Wyoming and the fossil fish most often seen for sale at nature museums and curiosity shops). This Knightia honors a different Knight—University of Wyoming professor Wilbur Clinton Knight (1858-1903), “an indefatigable student of the paleontology of the Rocky Mountains.”

These are the ones we know about among fishes. Do you know of any others?

* The lower-case for “algae, fungi, and plants” indicates that these terms are not formal names of clades, but rather historical names traditionally studied by phycologists, mycologists, and botanists.

** “Faber,” by the way, is also an ancient name for the John Dory, dating to at least “Halieutica” (“On Fishing”), a fragmentary didactic poem spuriously attributed to Ovid, circa AD 17.

28 September 2016

28 September 2016

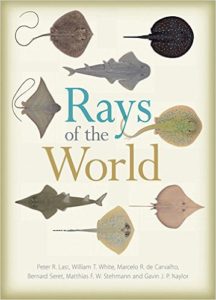

Hypanus Rafinesque 1818

In preparation for the upcoming publication of the book Rays of the World, its authors have been busy publishing papers describing new ray taxa and redefining the ordinal and familial limits of batoid fishes. In a new classification of whiptail stingrays (Myliobatiformes: Dasyatidae), the authors resurrected the name Hypanus from the synonymy of Dasyatis.

As mentioned in previous Names of the Week, names coined by the eccentric naturalist Constantine Samuel Rafinesque (1783-1840) often make little or no biological or grammatical sense. Hypanus is no exception.

In a brief, 67-word paragraph, Rafinesque proposed two new North American ray genera he believed formed part of a “natural tribe”: Hypanus, which, according to Rafinesque, has dorsal and anal fins, and Uroxys (now a synonym of the butterfly ray genus Gymnura), which does not. Based on this, we can surmise that Hypanus derives from hyp[er]-, meaning over or above, and anus, meaning anal, presumably referring to the fact that Hypanus has fins above (dorsal) and below (anal). The fact that Hypanus say, the type species, does not have a dorsal fin is irrelevant; Rafinesque saw a dorsal fin (assuming he even handled an actual specimen, which we doubt) and that’s all that matters.

Another explanation is that Rafinesque was referring to the dorsal and ventral folds along the tail of Hypanus say. There is no internal evidence for this interpretation, but it seems plausible.

It’s ironic that the authors who resurrected Hypanus go to great efforts to clarify the morphological and molecular limits of the genus, only to bestow it with a clumsy name coined in a perfunctory paragraph that clarified nothing.

21 September 2016

21 September 2016

Vinciguerria poweriae (Cocco 1838)

This week, we commemorate the 24 September birthday of a pioneering scientist we had never heard of until we researched the etymology of this marine lightfish (Phosichthyidae), which was named in her honor 178 years ago. Every biologist who has studied aquatic animals in an aquarium — indeed, every home aquarist — has this woman to thank.

Born in France, Jeanne Villepreux-Power (1794-1871), was a seamstress who decided to turn her fascination for marine creatures into her career. Entirely self-taught, she became a world authority on mollusks, argonauts and fossil shells. She was the first person to demonstrate that the octopus produced its own shell, rather than acquiring it from a different organism the way a hermit crab does. And she created what is believed to be the first aquarium in 1832.

In addition, Villepreux-Power contributed to the field of aquaculture with the idea that young fish could be raised in submerged cages until big enough to survive or avoid predators and be reintroduced to the wild. This is the basic idea behind the modern-day fish hatchery.

In 1843, a storm sunk a cargo ship that was transporting nearly all of Villepreux-Power’s research, equipment, work and drawings. Twenty-five years of study was lost at sea. While she continued to write, she discontinued her research forever.

In naming a fish after her — a rare honor in an age when men dominated science and academia — Italian ichthyologist and pharmacist Anastasio Cocco (1799-1854) called Villepreux-Power both a friend and a colleague. A century-and-a-half later, in 1997, her name was given to a crater on Venus discovered by the Magellan probe, making her one of the very few humans whose name is honored on two different worlds.

We need to spend more time researching this, but is Vinciguerria poweriae the first fish species named after a woman?

Australian Lungfish, Neoceratodus forsteri. From: Krefft, J. L. G. 1870. Description of a gigantic amphibian allied to the genus Lepidosiren, from the Wide-Bay district, Queensland. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 1870 (pt 2): 221-224.

14 September 2016

Neoceratodus forsteri Krefft 1870

When Gerard Krefft named the Australian Lungfish after his old friend William Forster, it was more than an honor. It was an apology, too.

Krefft (1830-1881) was curator of the Australian Museum. Forster (1818-1882) was a politician, at the time serving as Minister of Lands for New South Wales. Forster owned large tracts of land in the Wide Bay-Burnett region of Queensland. He tantalized Krefft with tales of a freshwater “fish” with a cartilaginous backbone. Early settlers (called squatters) relished its pink flesh and called it “Burnett salmon.” Surely no such fish can exist, Krefft believed. He insisted that Forster was mistaken.

But Forster wasn’t mistaken. One day he presented Krefft with a box containing two salted fish. Their entrails had been removed, but that didn’t matter. Krefft was amazed by what he saw. According to Krefft, the conversation went like this:

Said Mr Forster: “Well Krefft, what are those fish?” Said I: “Cannot tell you till you allow me to examine them.” Said Forster: “Do so, you are welcome to them. I present them to you, if you will name them after me.” I replied: “I will,” took my knife out, exposed the teeth and told Forster: “Never saw anything to equal this in my life.” “Are they new?” said Forster. “No, I said, “They are old as the mountains of Australia, and if you will let me alone we will make a fortune with these fishes.” “Well” (were his last words) “take them away, do what you like with them but make the discovery known in tomorrow’s Herald.” Of course I had to keep my word and other people earned the benefit.

Krefft kept his word. He announced the discovery of an Australian fish that had both lungs and gills not in a scientific journal, but in a letter to the editor in the 17 January 1870 edition of the Sydney Morning Herald. And there he published the name, Ceratodus forsteri, believing it was a living representative of a cosmopolitan genus of Triassic aquatic animals proposed by Louis Agassiz in 1838. Previous paleontologists believed Ceratodus were allied to sharks. But with fresh material now in hand, Krefft believed the genus was allied to salamanders. In fact, he called the lungfish not a lungfish, but a “great amphibian.”

“In honour of the gentlemen who presented this valuable specimen to the Museum,” Krefft kept his word and named it after Forster. In addition, Krefft said that he named the fish “in justice” to his friend, “whose observations I questioned when the subject [of an amphibious fish] was mentioned years ago, and to whom I now apologize.”

Krefft published a formal and more detailed description of the lungfish later that year. And at some point, he composed this short verse for his son:

Lucullus ate Muraena rare,

In Rome the daintiest dish,

And Squatters on the Burnett dined

On geologic fish.

Dr. Sylvia Earle, National Geographic Explorer-in-Residence, presents President Obama with a picture of the fish that was named after him. Photograph by Brian Skerry, National Geographic

7 September 2016

Name — that’s not yet officially a name — of the week

Last Friday, the National Geographic Society announced that a new species of basslet (Serranidae) of the genus Tosanoides will be named after U.S. President Barack Obama:

Watch the video in the linked story. It’s fun to see President Obama struggle to pronounce Tosanoides. And, no doubt unfamiliar with zoological nomenclature, he also clumsily includes “Pyle” — referring to senior author Richard Pyle — as part of the name.

Obama was honored for expanding the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, where this basslet is endemic. Roughly twice the size of Texas, the Monument is the largest swath of protected land or water in the world.

We refrain from printing the full name until it’s formally published, but it’s clearly evident in the plaque that Obama is holding.

This isn’t the first fish species named after Obama. Teleogramma obamaorum, a deepwater cichlid from the Congo, was a “Name of the Week” in 2015. And in 2012, a darter (Percidae) from Tennessee was named Etheostoma obama.

According to the linked article, Obama also has a trapdoor spider, a species of lichen, a puffbird, a parasitic hairworm (Paragordius obami) that infects crickets, and an extinct lizard called Obamadon named after him. Curious about the parasitic hairworm, we checked out its etymology:

“This species is named in honor of the 44th president of the United States of America, Barack H. Obama, whose father was raised and paternal step-grandmother resides in Nyang’oma Kogelo (Kogelo), Kenya, 19 km northwest of the type locality.”

12/26/2016 UPDATE: The name is now official: Tosanoides obama Pyle, Greene & Kosaki 2016.

Periophthalmus pusing. From: Jaafar, Z., G. Polgar and Y. Zamroni. 2016. Description of a new species of Periophthalmus (Teleostei: Gobiidae) from the Lesser Sunda Islands. Raffles Bulletin of Zoology 64: 278-283.

31 August 2016

Periophthalmus pusing Jaafar, Polgar & Zamroni 2016

Mudskippers are neat fishes. And this new mudskipper species has a pretty neat name.

Writing in the Raffles Bulletin of Zoology, the authors separate this new species from the similar P. gracilis based on a number of characters, including the number of spines in the first dorsal fin. It’s presently known only from the Lesser Sumba Island of Indonesia, where it’s known as “Ikan Pusing” among the coastal Indonesians. Ikan means fish. Pusing means giddy. According to the locals, eating these mudskippers causes headaches and, you guessed it, giddiness.

The generic name Periophthalmus predates the specific name by some 215 years. Coined by Bloch & Schneider in 1801, several online references explain the name this way: from the Greek peri (around) and ophthalmon, eye, referring to the mudskippers’ wide visual field.

While the translation is correct, the explanation is not. True, mudskippers can move their eyes independently, and their turreted position creates two 180° fields on each side, as well as above and below the fish. But we believe Bloch & Schneider named the genus using the anatomical term periophthalmum, a thin skin (usually seen in birds) that draws over the eyes to protect them without shutting the eyelids.

Bloch & Schneider use just five words to diagnose the genus: “Pinnae pectorales manuformes, oculi palpebrati” — pectoral fins like hands, eyes with eyelids. Sure enough, Periophthalmus mudskippers have a lower eyelid fold.

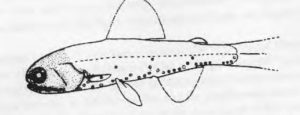

Diaphus minax. From: Nafpaktitis, B. G. 1968. Taxonomy and distribution of the lanternfishes, genera Lobianchia and Diaphus, in the North Atlantic. Dana Report No. 73: 1-131, Pls. 1-2.

24 August 2016

Diaphus minax Nafpaktitis 1968

A picture is worth a thousand words, the old saying goes. But this one is worth just one. Lanternfish expert Basil Nafpaktitis chose the Latin word for “threatening” (and the source for the Old French and Middle English word “menace”) to describe this lanternfish from the Western Atlantic. The epithet, he said, refer to its “angry looks.”

Here is the illustration that accompanied the original description. Could you have selected a more appropriate name?

Constantine Samuel Rafinesque (1783-1840), enamel miniature at Transylvania University, Lexington, Kentucky, circa 1810.

17 August 2016

Shedding light on the lanternfish name Myctophum Rafinesque 1810

Two weeks ago, we mentioned that many names coined by Constantine Samuel Rafinesque (1783-1840) sometimes make little grammatical or biological sense. Indeed, philological scholars have used words like “monstrosities” and “butchery” to describe his command of Greek and Latin and his idiosyncratic approach to spelling. Myctophum — the type genus of the lanternfish family Myctophidae — is another case in point. In fact, apparent confusion regarding the meaning (or spelling) of this name dates back to 1838. We believe the analysis below is the first time the true meaning of the name has been revealed.

In 1838. Italian naturalist-pharmacist Anastasio Cocco (1799-1854) changed the spelling from Myctophum to Nyctophum. Since lanternfishes possess photophores and luminous glands, and since large numbers of them migrate to the surface at night, it’s easy to assume that Cocco’s new spelling is derived from nyctos and phos, the Greek words for night and light, respectively. But it’s not clear whether Cocco was correcting the original spelling of the name or misspelling it himself. What is clear, however, is that Rafinesque had no idea that lanternfishes were luminous. Rafinesque mentioned that his specimen had shiny spots, but he did not indicate that these spots glowed in the dark.

We believe that Myctophum is the spelling that Rafinesque intended, but its meaning has nothing to do with luminescence. Instead, we translate it this way: myktos, nose or nostril and [l]ophus, crest or ridge. (Note: When combining words to coin names, Rafinesque sometimes deleted what he believed were unnecessary consonants, hence the missing “l” from “lophus” — one of the reasons his names are so hated by anal-retentive philologists.) This translation aligns with this phrase from his description of the type species, Myctophum punctatus: “big nose with two oblong openings separated by a ridge, and margined by another” (translated from the Italian).

Whether M. punctatum actually has a big nose is open to interpretation. According to Jordan & Evermann’s Fishes of the North and Middle America (vol. 1, 1896), the snout of M. punctatum is “very short, with a very inconspicuous keel on upper edge, its length scarcely 1/3 diameter of eye.” Despite whatever faults that name Myctophum may have, Rafinesque provided sufficient clues for us to understand its meaning. Unlike the fish he was describing, he did not leave us entirely in the dark.

Trimma fucatum, 21.0 mm SL male paratype, Phuket, Thailand. Courtesy: Richard Winterbottom, Royal Ontario Museum.

10 August 2016

The Harlot Pygmy Goby, Trimma fucatum Winterbottom & Southcott 2007

Usually we don’t feature common names, but this one’s too provocative to pass up.

Trimma Jordan & Seale 1906 contains nearly 100 species of small (<30 mm SL), often colorful gobiids, primarily associated with Indo-Pacific coral reefs. They are known commonly as pygmy gobies because of their small size. Trimma fucatum occurs over patch reefs and coral slopes in the Andaman Sea of Thailand at depths ranging from 0-23 m.

Jordan and Seale did not explain the meaning of the generic name Trimma. According to our dictionary, Trimma is Greek for “anything rubbed or crushed.” We asked Trimma taxonomist Richard Winterbottom (who co-described T. fucatum) about this. His offered a slightly different translation for Trimma — “something ground exceedingly fine” — and suggests that the name was chosen because these gobies are very small.

The specific name fucatum is Latin for painted, colored or rouged and refers to its red markings on and around the preopercle. What grabbed out attention was the authors’ suggested common name for the species: Harlot Pygmy Goby — harlot being a Middle English word for prostitute or promiscuous woman.

We assume that the common name is meant to draw a descriptive parallel between the goby’s red preopercular markings and the over-abundance of red facial make-up that some prostitutes apply to make themselves more attractive or to announce their availability to potential clients. We asked Dr. Winterbottom for confirmation. This was his response:

“As for the interpretation of the inference of the common name, I plead the Fifth Amendment.”

3 August 2016

Notropis atherinoides Rafinesque 1818

We’re always happy to feature the work of our good friend, fish ecologist Jan Jeffrey Hoover, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ Engineer Research and Development Center in Vicksburg, Mississippi. Jan has been a good friend of The ETYFish Project since the beginning and is one of our go-to people for finding hard-to-find literature.

In this video, you’ll see Jan and students from the University of Buffalo investigating the swimming ability of the Emerald Shiner, Notropis atherinoides, a once-abundant cyprinid in the Great Lakes Region. Data from this study will be used to design and build fish-passage structures that help the cyprinid navigate man-made barriers on the way to its spawning grounds in the upper Niagara River and Lake Erie. The Emerald Shiner is a keystone species and a chief food source for various Great Lakes sportfish. Its numbers have declined 75% in recent years.

Notropis atherinoides was named and described by the brilliant but eccentric naturalist Constantine Samuel Rafinesque (1783-1840). One aspect of his eccentricity was his penchant for coining names that make little grammatical or biological sense. Notropis atheriniodes — the type species of the speciose North American genus Notropis — is one example.

The meaning of the specific name atheriniodes is clear. –oides is a suffix that denotes similarity or resemblance. In this case, Rafinesque is noting that the Emerald Shiner resembles the silversides of the genus Atherina, which indeed it does. (Rafinesque also believed the two genera were closely related.) The meaning of Notropis is clear as well but enters the “misnomer” category of biological names. Notos means back and tropis means keeled, as Rafinesque himself helpfully pointed out, referring to the minnow’s “carinated nearly strait” back.

Trouble is, the Emerald Shiner does not have a keeled back. Nor do any of its 89 or so congeners.

What was Rafinesque thinking? In 1954, American ichthyologists Reeve M. Bailey and Robert Rush Miller hazarded a guess — the keeled back was “probably an artifact resulting from improper preservation.” It’s possible that Rafinesque’s specimen had shrunk, creating the appearance of a keel-like ridge along the pulled-back skin of the dorsal surface.

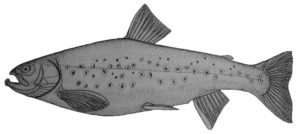

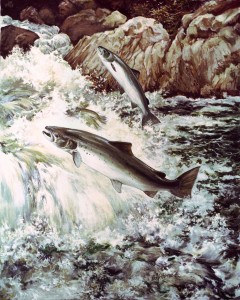

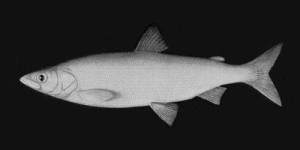

Salvelinus krogiusae. From: Chereshnev, I. A., V. V. Volobuev, A. V. Shestakov and S. V. Frolov (eds.). 2002. Salmonoid fishes of the Russian North-east. Dal’nauka, Vladivostok: Russian Academy of Sciences, Far-Eastern Branch.

27 July 2016

Salvelinus krogiusae Glubokovsky & Chereshnev 2002

Last week, we provided an example of how our etymological research led the editors of the Catalog of Fishes to change the authorship of the name of a fish. This week we highlight another.

Salvelinus krogiusae is a landlocked species of char (Salmonidae) that occurs in Dal’nee Lake in the Paratunka River basin of Kamchatka, Russia. The Catalog of Fishes dated its name to a chapter on the systematics of chars in Elgygytgyn Lake (an impact crater located in northeast Siberia) from a 1993 Russian book called The Nature of the Elgygytgyn Lake Crater. Authorship was given as “Glubokovsky, Frolov, Efremov, Rybnikova & Katugin 1993.” Assuming this char was named after someone—probably a woman based on the feminine gender—named Krougius, we tracked down a copy of the book to learn more. We discovered that S. krogiusae was merely mentioned in the chapter and not described. Without a valid description, S. krogiusae was clearly a nomen nudum, a “naked” and therefore invalid name.

We continued looking and eventually found a valid description in a later Russian book, Salmonoid Fishes of the Russian Northeast, published in 2002. As it turns out, char biologist M.K. Glubokovsky first proposed the name S. krogiusae in an unpublished 1990 doctoral dissertation. He then reused the name in his 1993 chapter, which the Catalog of Fishes and other resources cited as the description without actually having seen it (which unfortunately happens with some Russian publications, which are hard to get in America). So that it is how “Salvelinus krogiusae Glubokovsky, Frolov, Efremov, Rybnikova & Katugin 1993” became “Salvelinus krogiusae Glubokovsky & Chereshnev 2002.”

Now, who is this Krogius for whom this char is named? It’s someone who’s virtually unknown outside of Russia — Russian ichthyologist Faina Vladimirovna Krogius (1902-1989), who studied the biology of Oncorhynchus nerka in Dal’nee Lake, Kamchatka, for 50 years. She also collected the type of S. krogiusae in 1938.

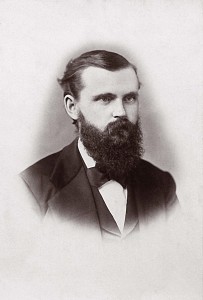

William Griffith in 1843. From: Makers of British Botany (1913).

20 July 2016

Schizothorax intermedius McClelland & Griffith 1842

Schizothorax is a genus of Central and Eastern Asian minnows sometimes called “snowtrout” because of their trout-like bodies and occurrence in cold, higher-elevation streams (an apparent example of evolutionary convergence). British medical doctor John McClelland (1805-1883) penned the original description of S. intermedius in 1842. He had been sent to India to explore for coal and study the efficacy of growing tea in that part of the world. An avid naturalist, he also was the editor of the Calcutta Journal of Natural History, in which the original description appeared.

Historically, McClelland has been cited as the sole author of S. intermedius. But while researching this name for The ETYFish Project, we noticed that McClelland had a collaborator. While the description itself appears on page 579 of the journal, McClelland provided a list of “Newly discovered species” on page 573. Here McClelland indicated the authorship of S. intermedius as “McClell. et Griff.” — “Griff.” being fellow British physician William Griffith (1810-1845).

Griffith did all the field work reported on in McClelland’s article. A botanist at heart, Griffith added fishes to his collecting chores while exploring Afghanistan and Iran, where S. intermedius occurs. He also composed detailed field notes and drew illustrations of the fishes in their life colors. He forwarded everything — notes, illustrations and specimens — to McClelland, who, as editor of the journal, prepared the material for publication, and, apparently, coined the new names. McClelland repeatedly credited Griffith for his contributions. In fact, the paper’s title reads: “On the fresh-water fishes collected by William Griffith, Esq., F. L. S. Madras Medical Service, during his travels under the orders of the Supreme Government of India, from 1835 to 1842.”

McClelland appears to have left India around 1847. His biography gets hazy after that. He died in 1883. Griffith died of a parasitic liver disease, presumably contracted in the field, just three years after McClelland published his notes. Griffith was quite sick for the final year or two of his life, but continued to work to the point of exhaustion and collapse. “No government ever had a more devoted or zealous servant,” McClelland wrote in an obituary of his colleague, “and I impute much of the evil consequences of his health, to his attempting more than the means at his disposal enabled him to accomplish with justice to himself.”

McClelland named a different species of snowtrout after Griffith — Oreinus griffithii — but it is now considered a junior synonym of Schizothorax plagiostomus Heckel 1838.

As for the name S. intermedius, its etymology is unexplained and unclear. We presume intermedius means that McClelland and Griffith believed this species to be intermediate in form among the five nominal Schizothorax species they discussed, but a comparison of their characters does not seem to support this interpretation.

Since McClelland is listed as the author of the article in which the name appeared, many ichthyologists have overlooked the fact that McClelland shared credit with Griffith as the author of the name. Last year, we alerted the editors of the online Catalog of Fishes that “McClelland 1842” should be changed to “McClelland & Griffith 1842. They agreed.

After 173 years, Griffith has finally gotten the credit his colleague believed he deserved.

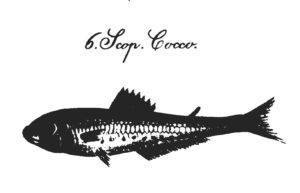

Sopelus (now Gonichthys) cocco. From: Cocco, A. 1838. Su di alcuni salmonidi del mare di Messina. Nuovi annali delle scienze naturali e rendiconto dei lavori dell’Accademia della Scienze dell’Instituto di Bologna con appendice agraria. Bologna Anno 1 Tomo 2 (fasc. 9): 161-194, Pls. 5-8.

13 July 2016

Gonichthys cocco (Cocco 1829)

Did Italian ichthyologist and pharmacist Anastasio Cocco (1799-1854) commit the sin of nomenclatural pride and name this lanternfish (Myctophidae) after himself? That is certainly the conclusion of Jordan and Evermann, who, in the first volume of Fishes of North and Middle America (1896), wrote that G. cocco was “Named for Anastasio Cocco, an Italian naturalist, who carefully studied the deep-sea fishes which he could secure.” As far as we know, no one has disputed this explanation of the name. Nor has anyone called Cocco out for this alleged sin. But if one digs a little deeper, a more definitive and satisfying explanation emerges.

Cocco described Scopelus cocco (as it was then called) twice. The first description, taking up less than half of a page, appeared in an 1829 note entitled “Su di alcuni nuovi pesci de’ mari di Messina” (“On some new fishes from the seas of Messina”). Cocco did not explain the name.

Cocco published a more detailed description in 1838, which Jordan and Evermann apparently overlooked. At the beginning of the account Cocco wrote: “When I first published the description of this beautiful Scopelo [Cocco’s vernacular version of Scopelus], I dedicated it to the memory of my dear father, who died very prematurely, and whose loss will never stop bringing me to tears” (translation).

According to a few online bios of Anastasio Cocco, his father was a physician and a scholar. We can find nothing more about the man, not even his first name. But his memory lives on in the name of a deep-sea fish and the words of a grieving son.

Diaphus confusus. From: Becker, V. E. 1992. Benthopelagic fishes of the genera Idiolychnus and Diaphus (Myctophidae) from the southeastern Pacific, with the description of two new species. Voprosy Ikhtiologii v. 32 (no. 6): 3-10.

6 July 2016

Diaphus confusus Becker 1992

This may be the only species of fish whose name reflects the author’s indecision in what to name it. It’s certainly the only one we’ve seen so far.

Diaphus confusus is a lanternfish (Myctophidae) that is known only to occur at depths of 545-560 m in the central part of the Sala y Gomez Ridge of the Eastern Pacific. Like many lanternfishes, it is primarily distinguished from its congeners based on the arrangement of photophores and luminous glands along its body.

Russian ichthyologist V. E. Becker described D. confusus in minute detail, cataloguing the many but exceedingly subtle ways it which it differs from the similar D. knappi of the Indo-West Pacific. When it came to its name, it seems that Bekker shrugged his shoulders and waved a nomenclatural white flag. Here is the “etymology” section (translated from Russian):

“The addition [selection?] of confusus (Latin for “confused” or “unclear”) reflects the absence of any clear diagnostic trait in this new species; this word well describes the author’s state of mind when searching for a name for this taxon.”

A few words about the generic name Diaphus. FishBase reports that it is derived from the Greek dis or dia, meaning “through,” and physa or phyo, meaning “to beget, to have as offspring” (with no explanation of how the name applies). This is another example of FishBase getting the translation wrong (a piece of misinformation that is compounded 80 times for each of the genus’ species). While the authors of the name, Carl Eigenmann and his wife Rosa, did not explain the etymology of Diaphus, our translation of the name is supported by details they provided in their description.

Our translation is this: Di– means two or divided, while phus is the latinization of the Greek phos, meaning light. According to the Eigenmanns, the distinguishing feature of the genus is presence of “phosphorescent spots divided into halves by a median black line.” The type species is Diaphus theta. “Theta” is the eigth letter of the Greek alphabet. It resembles the digit zero with a horizontal line through it: θ. It’s easy to see how “divided light” refers to how most or all of the photophores of D. theta are divided by a horizontal septum of black pigment.

From: Martín Salazar, F. J., I. J. H. Isbrücker and H. Nijssen. 1982. Dentectus barbarmatus, a new genus and species of mailed catfish from the Orinoco Basin of Venezuela (Pisces, Siluriformes, Loricariidae). Beaufortia v. 32 (no. 8): 125-137.

29 June 2016

Dentectus barbarmatus Martín Salazar, Isbrücker & Nijssen 1982

We are featuring this name not because it’s etymologically interesting, but because one of the illustrations that accompanied the original description is unlike any we’ve ever seen.

Dentectus is a monotypic genus of suckermouth armored catfishes (Loricariidae) from tributaries of the northern margin of the Orinoco Basin in Venezuela. The species was first collected in 1950 by the pioneering Venezuelan ichthyologist Augustin Fernández-Yépez (1916-1977). In 1968, he and his associate Félipe J. Martín Salazar (b. 1930) began to sort through the fishes that Fernández-Yépez had collected over the years but had not yet described. This catfish was one of them. Ten years later, when they were preparing to finish their work, Fernández-Yépez died. However, he left behind “numerous very accurate drawings and sketches of his specimens.” Martín Salazar completed some of the sketches and, with the help of catfish taxonomists Isaäc Isbrücker (b. 1944) and Han Nijssen (1935-2013), published a paper that completed Fernández-Yépez’ work and honored his career.

We like the illustration because it shows ventral and dorsal views of the catfish’s head in a simultaneous, side-by-side fashion. We’ve seen many ventral and dorsal views before, but never juxtaposed in this way. It’s a pretty cool trick.

As for the names, Dentectus is a combination of dens, teeth and tectus, covered, concealed or disguised, referring to how the teeth are “invisible” in normally preserved specimens (but are easily observed in specimens that are cleared and stained). The specific name combines barbus, beard with armatus, furnished with weapons, and refers to dermal ossifications (small scutelets) along the outer margin of the maxillary barbels.

22 June 2016

Varicus lacerta Tornabene, Robertson & Baldwin 2016

It’s been a good year for Godzilla.

On 8 June, a trio of ichthyologists from the Smithsonian published the description of a new goby from the southern Caribbean. The specific epithet “lacerta” (Latin for “lizard”) refers to its reptilian appearance — bright yellow and orange coloration, green eyes, disproportionately large head possessing raised ridges of papilla, and multiple rows of recurved canine teeth in each jaw. The researchers also proposed a common name for the species — the Godzilla Goby, referring to the radioactive reptilian monster from the sea that appeared in Japanese and subsequent English-language science-fiction films.

But that’s not the only Godzilla news of the year. According to the Anime News Network, the 61-year-old movie legend was recently promoted to tourism ambassador and made an honorary citizen of Tokyo’s Shinjuku ward. A life-sized Godzilla head has been set up atop Kabuki-cho’s TOHO Cinemas Shinjuku.

“Godzilla is a character that is the pride of Japan,” Shinjuku Mayor Kenichi Yoshizumi said. Any location destroyed by Godzilla in a movie, the mayor added, will enjoy good fortune in real life.

Phone calls to Godzilla asking for comment on the new goby were not returned.

The description of the Godzilla Goby is open-access.

Head of holotype (live) of Compsaraia samueli (male, 226 mm). From: Albert, J. S. and W. G. R. Crampton. 2009. A new species of electric knifefish, genus Compsaraia (Gymnotiformes: Apteronotidae) from the Amazon River, with extreme sexual dimorphism in snout and jaw length. Systematics and Biodiversity v. 7 (no. 1): 81-92.

15 June 2016

Compsaraia samueli Albert & Crampton 2009

In celebration of Father’s Day this Sunday, we feature a name in which a son honors his father. Except that when the name was published, there was no indication that a father was being honored.

Compsaraia samueli is a ghost knifefish (Apteronotidae) that occurs in the Western Amazon River basin of Peru and Brazil. The authors credit “Dr. Samuel Albert” for providing them with specimens of the type series, but did not indicate who he is. Suspecting that Dr. Albert and the senior author, James Albert, are related, we contacted the latter Albert, who confirmed that the fish was named for his father, a physician. He also provided the inside story of how this knifefish was collected, information not included in the paper introducing this species to science.

In April 2005, my father accompanied an expedition I led to the Peruvian Amazon, Department of Loreto, to collect electric fishes. … My father purchased the specimens that would end up becoming the type series of Compsaraia samueli from some indigenous fishermen at a local fish market near Iquitos. He immediately recognized these specimens as different from all the other electric fishes we had been collecting by the prominent elongate jaws of mature males. We now know male C. samueli use these elongate jaws in aggressive interactions including jaw-locking behaviors, and that the species inhabits deep channels of large rivers throughout much of lowland Amazonia, although sexually mature males with elongate jaws are still rare in museum collections.

James Albert added that his father was 71 years old at the time of that expedition. This fact reminded Albert of something John Haseman, a student of Carl Eigenmann and collector of neotropical fishes, wrote in 1911:

“Fishing in South America is by far the most dangerous of all forms of scientific exploration. No man over 50 years of age should attempt to enter this region.”

To fathers of all ages, Happy Father’s Day!

![The Murray Hardyhead, Craterocephalus fluviatilis, from McCulloch, A. R. 1912. Notes on some Australian Atherinidae. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Queensland v. 24: 47-53, Pl. 1. [Appeared first as a preprint in 1912.]](https://etyfish.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Craterocephalus_fluviatilis-300x105.jpg)

The Murray Hardyhead, Craterocephalus fluviatilis, from McCulloch, A. R. 1912. Notes on some Australian Atherinidae. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Queensland v. 24: 47-53, Pl. 1. [Appeared first as a preprint in 1912.]

Craterocephalus McCulloch 1912

Craterocephalus is a genus of brackish or freshwater silverside (Atherinidae) from Australia and New Guinea, where they are known as hardyheads. There are 26 species in the genus.

According to FishBase, cratero- derives from the Greek krater, meaning crater or mixing bowl, and cephalus for head. The book Freshwater Fishes of North-Eastern Australia repeats this translation, adding that the name possibly refers to the “strong or sturdy head” of species in the genus. Our very good friend Peter Unmack (pers. comm.) suggests that the name could refer to the somewhat concave head profile seen in larger Craterocephalus individuals, but comparing a slight concavity to a crater seems a bit of a stretch.

Instead of crater or mixing bowl, it appears more likely that cratero– is derived from the Greek krateros, meaning strong, hard or sturdy. While McCulloch did not describe the head in this manner, he did state that C. fluviatilis (the type species) and C. maculatus (currently a synonym of C. stercusmuscarum) both possess “large, cycloid, concentrically striated” scales on the body that “extend forwards on to the upper part of the head …”. So maybe the head appears strong or sturdy because of these scales. The common name “hardyhead” further supports the notion that cratero– means hard.

The common name “hardyhead” is the key to a third explanation, one we suspect is closest to the truth. It is easy to assume that “hardyhead” is an English transliteration of “Craterocephalus,” but it appears that it is the other way around. Use of the term “hardyhead” for silversides in Australia dates to at least 1881, when it was reported that Sydney fishermen referred to Atherinomorus pinguis (now known as A. vaigiensis) by that name. This was three decades before the description of the genus Craterocephalus (as part of the description of C. fluviatilis). What’s more, McCulloch quoted field notes from ichthyologist David G. Stead, who called C. fluviatilis a “Freshwater hardyhead.” Our best guess is that McCulloch rather cleverly provided a Latin version of a local Australian name.

Which brings us to an even deeper mystery: Why are hardyheads called hardyheads? No one seems to know. We posed the question to Dr. Walter Ivantsoff, an authority on the genus. His answer: “Probably a name given by fishermen. In earlier years, pulling a seine would take out hundreds [of Hardyheads] in one haul with a number [of them] surviving a little while. Also the head of atherinids appears to be bony, the epithelium is thin, and the bone seems to be naked. So I can only conjecture.”

Carte-de-visite of James G. Swan just before departing for the Queen Charlotte Island, British Columbia. From the Franz R. and Kathryn M. Stenzel Collection of Western American Art, Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Courtesy of Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut.

1 June 2016

Bothragonus swanii (Steindachner 1876)

When Austrian ichthyologist Franz Steindachner described this poacher (Agonidae) in 1876, he credited a “Dr. Swan” for handing him the type specimen during Steindachner’s visit to Port Townsend, Washington, USA, in 1872. Steindachner said nothing more about this Dr. Swan. He didn’t even mention his first name. Steindachner’s cursory reference disguises the fact Swan lived a colorful, kaleidoscopic life. In fact, it could be said that handing a dead fish to Steindachner was one of the least interesting things he did.

Born in Massachusetts in 1818, James G. Swan pursued a career in maritime trade and law in New England, but was fascinated by the geography and native peoples of the Pacific Northwest. In the 1840s, he joined the California Gold Rush, leaving his wife and two children behind. He worked as a shipbuilder and oysterman while learning the language of the Chinook Indians. This led to a job for the U.S. government working as a translator for treaty negotiations with the Indians of what was then called the “Washington Territory.”

In 1857, Swan returned east, published a book about his adventures, and worked as a personal secretary to Isaac Stevens, the Washington Territory’s delegate to the U.S. Congress. But his love for the Northwest pulled him back across the country, this time for good. He divided his time between Port Townsend and the Makah Indian Reservation at Neah Bay.

In 1862, Swan became a schoolteacher at the Makah Reservation, teaching English, farming and sewing. He was torn between urging the Makah people to adapt to the white-man’s ways while preserving their culture and identity. Under pressure to teach Christianity to the Makah, Swan resigned in 1866 and moved to Port Townsend.

Here the tireless Swan became a lawyer specializing in maritime law. He later became a district court judge and took on several other government positions. But Swan hated sitting behind a desk and disliked the work. So he frequently took leaves of absence to go in search of adventure. He worked as an agent for the Northern Pacific Railway, surveying routes and potential termini. Freelancing for the Smithsonian Institution, he collected Indian artifacts in British Columbia and Alaska. (The Smithsonian later published Swan’s ethnography of the Makah, a seminal work that is still used today.) He also free-lanced for the U.S. Fish Commission, which probably put him in position to meet Steindachner in 1872.

Swan attempted to parlay his government connections into entrepreneurial success and failed each time. Every dollar he made he lost in some ill-fated real-estate venture. Believing that Willapa Bay, Washington, might become a great harbor, he lost money investing in lands around it. He lost money the same way in Port Townsend, believing that that town would, based on his recommendation, become a railroad terminus. It did not. Instead, Port Townsend became the terminus for Swan himself. He died there in 1900.

Visit Port Townsend today and you will find a Swan Hotel and a Swan School. Visit in April and you can attend the Jefferson County Historical Society Founders’ Day celebration, in which a living-history interpreter dons period clothes and makes pretend he is James G. Swan. Do you think he mentions that a fish is named after him?

Embiotoca jacksoni, from: Tarp, F. H. 1952. A revision of the family Embiotocidae (the surfperches). Fish Bulletin of the Division of Fish and Game of California No. 88: 1-99.

25 May 2016 (revised 9 November 2018)

Embiotoca jacksoni Agassiz 1853 and Embiotoca caryi Agassiz 1853

Harvard zoologist-paleontologist Louis Agassiz (1807-1873) named one of these surfperches after the man who reported their viviparity. He named the other surfperch after the man who proved it.

In 1852, A. C. Jackson — we can find no other biographical material about him — had been hired by the U. S. Navy to survey potential port locations in San Francisco Bay. While fishing, he caught an unusual fish, cut it open, and was surprised to see living fish inside, which he described as “perfect miniatures of the mother.” He sketched an outline of the fish and sent it along with a letter to Agassiz, then the most famous zoologist in the country.

Agassiz doubted the veracity of Jackson’s “extraordinary” claim that this fish gave birth to live young and “suspected some mistake.” In a return letter, he asked Jackson to send him some specimens, but Jackson was unable to do so. Agassiz then enlisted the help of his brother-in-law, Thomas Cary (1824-1888) of San Francisco, a businessman and amateur naturalist, “to be on the look out for this fish.” After a search of several months, Cary came through. Agassiz — who famously never accepted Darwin’s theory of evolution — finally accepted Jackson’s claim.

“After a careful examination of the specimens,” Agassiz wrote, “I have satisfied myself of the complete accuracy of every statement contained in Mr. Jackson’s letter of February, 1852, and I have since had the pleasure of ascertaining that there are two very distinct species of this remarkable type of fishes, among the specimens forwarded to me by Mr. Cary. I propose for them the generic name of Embiotoca, in allusion to its very peculiar mode of reproduction.”

Embiotoca is derived from the Greek embios, living (or perhaps living within), and tokos, offspring, referring to how the mother carries and nourishes her young in-utero.

Agassiz continued: “The perseverance and attention with which Messrs. Jackson and Cary have for a considerable length of time been watching every opportunity to obtain the necessary materials for a scientific examination of these wonderful fishes, has induced me to commemorate the service they have thus rendered to zoology by inscribing with their names the two species now in my hands, and which may be seen in my museum in Cambridge, labelled Emb. Jacksoni and Emb. Caryi.”

Agassiz never changed his mind about evolution. “I trust to outlive this mania,” he said in an 1867 letter. Alas, he did not.

Macroparalepis affinis, from off Madeira, 129 mm SL. From: Harry, R. R. 1953. Studies on the bathypelagic fishes of the family Paralepididae. 1. Survey of the genera. Pacific Science v. 7 (no. 2): 219-249.

18 May 2016

Macroparalepis Harry 1953

Search virtually every online database and consult nearly every printed reference on the barracudina genus Macroparalepis, and you’ll see that “Burton 1934” is the author and date of the taxon. Consult some pre-1990 references and you’ll see that authorship is attributed to “Ege 1933.” Last month, the Catalog of Fishes (CoF) listed Burton as the author. As of 2 May 2016, this indispensable taxonomic resource now credits “Harry 1953.”

You have The ETYFish Project to thank for that. Or blame.

The genus Macroparalepis was originally proposed by Danish biologist Vilhelm Ege (1887-1962) in 1933. Ege did not provide an etymology but we can surmise that the “macro-“ part of the name means “long” and refers to the genus’ longer, more elongate body compared to Paralepis, i.e., “long Paralepis.” Ege described nine new species under the new name and “Ege 1933” stood as the authorial source of the genus. But that changed in the 1990s, when the Catalog of Fishes team at the California Academy of Sciences realized that Ege did not designate a type species for the genus from among the nine he described. According to ICZN Art. 13.3, every new genus-group name published after 1930 must be accompanied by the fixation of a type species in the original publication (or be expressly proposed as a new replacement name) in order to be available. Since Ege’s 1933 paper failed to meet this requirement, authorship of Macroparalepis must then be credited to the next available usage of the name. The CoF team determined that the 1934 entry of Macroparalepis into the Zoological Record — the unofficial register of scientific names in zoology — satisfied Art. 13.3. This made the editor-compiler of the ZR’s fish section, someone named Burton, the author of Macroparalepis because he designated a type species (M. danae).*

We were curious about this Burton. Who was he? Did he have any background in ichthyology? Or was he merely an efficient editor-compiler whose name become linked with an entire genus of organisms simply through a nomenclatural technicality?

We learned that “Burton” was Maurice Burton (1898-1992), a student at King’s College (London) who worked as a compiler for the Zoological Record. He later became a sponge biologist, popular science writer and encyclopedist, and a skeptic of the Loch Ness Monster. It appears that he had no special training or interest in fishes.

Wishing to leave no stone unturned, we tracked down a copy of the 1934 Zoological Record (no easy task). Much to our surprise we discovered that Burton did not designate a type species contrary to what the CoF reported. Instead, he merely listed the species described in Ege’s monograph in the same order in which Ege described them (with the putative type species, M. danae, being the first name listed). Based on ICZN Art. 13.3, Macroparalepis was still not validly named.

Macroparalepis languished in obscurity for the next two decades until Robert R. Harry, then Assistant Curator of Fishes at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, revised the family Paralepidae in 1953. He clearly designated Macroparalepis affinis as the type species, making him by rule the author of the genus. We sent our findings to the CoF editors and they agreed.

And that is how Macroparalepis Ege 1933 became Macroparalepis Burton 1934 and now Macroparalepis Harry 1953.

*The current online edition of the Catalog of Fishes indicates that Burton designated M. affinis as the type species, whereas the hardcopy Catalog of the Genera of Recent Fishes (1990) indicates M. danae. Clearly there is confusion!

11 May 2016

11 May 2016

Trichomycterus dali Rizzato, Costa, Trajano & Bichuette 2011

Today, May 11, is the 112th anniversary of the birth of the Spanish surrealist painter Salvador Dali (1904-1989). Dali was a larger-than-life figure whose eccentric and grandiose behavior often drew more attention than his art. In a 2010 British poll, his flamboyant and iconic mustache was voted the most famous mustache in the world.

In 2011, a new species of pencil catfish (Trichomycteridae) was described from flooded limestone caves in the State of Mato Grosso do Sul in central Brazil. It’s a typically troglomorphic fish, with reduced eyes and a depigmented body coloration, described as white tending towards translucent. Perhaps its most distinctive feature is its very long barbels, especially the nasal barbel (99.3-143.5% of head length) and the maxillary (97.0-131.3% of head length). These barbels are presumed to be a sensory adaptation to its permanently dark cave habitat, where eyes are useless.

The catfish was named after Salvador Dali, referring to his famously long mustache and this catfish’s very long barbels.

Boops boops in Karpathos, Greece. Photo by Roberto Pillon. Courtesy: FishBase.

4 May 2016

Boops boops (Linnaeus 1758)

Linnaeus is credited with officially naming Sparus boops, a species of seabream from the eastern Atlantic and the seas of southern Europe, in 1758, but the specific epithet actually dates to anatomist-naturalist Guillaume Rondelet (1507-1566) in the 1550s. Cuvier proposed the genus Boops to house Sparus boops in 1814, creating the tautonym Boops boops.

Despite its appearance, “Boops” does not rhyme with “Oops!” Most sources indicate that the name translates as bo, ox, and ops, eye, and refers to its large eyes. If so, the name should be pronounced “bow ops.” There is some evidence, however, that the name is a corruption of “box,” an ancient name for the fish which is still called Bogue or Boga in southern Europe. If this etymology is correct, then perhaps it should be pronounced “bops” or “boaps.”

One thing is for certain. However you say it, Boops boops is a funny looking name.

Esox masquinongy, illustrated by H. L. Todd, courtesy of Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of Natural History, Division of Fishes.

27 April 2016

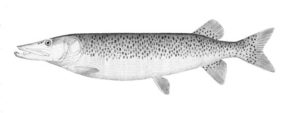

Esox masquinongy Mitchill 1824

Last week, we analyzed the generic name Morone, proposed by American naturalist-physician Samuel L. Mitchill in 1814. This week, we take a look at another Mitchill name, that of the Muskellunge, or Muskie, a large North American gamefish in the pike family Esocidae.

Unlike Morone, there is little mystery about the meaning of “masquinongy.” It is almost certainly derived from the Native American (Ojibway, or Chippewa) name for this species, a combination of mask, meaning ugly, and kinongé, meaning fish. But the name is now mired in something of a muddle. Last year, new information came to light that questions whether Mitchill is the technically acceptable author of the name.

Mitchill proposed the name back in the day when new-species descriptions in America sometimes appeared in daily newspapers. Trouble is, very few people actually saw the description that Mitchill published. Instead, taxonomists from David Starr Jordan to the present relied on a citation to Mitchill’s article that appeared in James E. DeKay’s 1840 monograph, Zoology of New-York . That citation read: “E. Masquinongy. Mitchell, Mirror 1824, p, 297.” (Note that DeKay misspelled Mitchill’s name.)

Based on DeKay’s citation, Jordan and others assumed Mitchill’s description appeared in the New York Mirror. Jordan searched for the article but could not find it. Yet he nevertheless treated the name as valid with Mitchill as author, a decision accepted without question by every fish taxonomist ever since.

Last year, ichthyologist Ronald Fricke, while tracking down fugitive references for the online Catalog of Fishes, finally tracked down Mitchill’s article. He found it not in the New York Mirror per se, but in a supplement that appeared in the newspaper called Minerva—an important bibliographic distinction DeKay failed to mention.

With Mitchill’s description in hand, Fricke made a surprising discovery—Mitchill did not propose a binomial. Instead, he called the fish “Masquinongy of the Great Lakes.” Nor did Mitchill indicate a genus, saying only that the fish was an “esox” (with a lowercase “e”) or a “pike.” It appears that DeKay created the impression that Mitchill formed a binomial when he cited the species as “E. Masquinongy. Mitchell” in 1840.