NAMES OF THE WEEK from: 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2023

24 April

What were they thinking?

Some fish names are misnomers, named for attributes the authors mistakenly believed the fish possessed. But some misnomers are just inexplicably wrong. In fact, the names run counter to the descriptions that accompanied their proposals. Here are five examples.

Cruriraja durbanensis (von Bonde & Swart 1923) — The Smoothnose Leg Skate occurs in the southeastern Atlantic Ocean off western South Africa. The type locality is Hondeklip Bay, a coastal village in the Namakwa district of South Africa’s Northern Cape province. The specific epithet “durbanensis” indicates that the skate is named for Durban, South Africa. Trouble is, Durban is over 1,600 km away, on the eastern coast of the country, on the Indian (not Atlantic) Ocean. The skate is not known to occur in Durban, yet its name suggests it does. What were von Bonde & Swart thinking?

Nematabramis alestes (Seale & Bean 1907) — This distant relative of rasboras and danios (Danionidae) is endemic to Mindanao, Philippines. Its name is derived from the Greek alestḗs (ἀλεστής), which means miller or grinder. Fishes with molariform teeth — used for crushing and grinding — are sometimes given this name (e.g., the African tetra genus Alestes). Yet the authors describe its pharyngeal teeth (the only teeth cyprinoids have) as “without evident grinding surface.” What were Seale & Bean thinking?

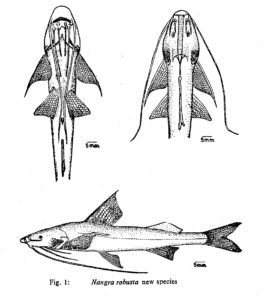

Nangra robusta. From: Mirza, M. R. and M. I. Awan. 1973. Two new catfishes (Pisces, Siluriformes) from Pakistan. Biologia (Lahore) 19 (1–2): 145–159.

Nangra robusta Mirza & Awan 1973 — The Latin adjective robustus/robusta has an interesting etymological history. Originally it meant “of oak or oaken” and, by extension, hard, firm or solid. Ichthyologists often use it to describe fat, stout or full-bodied fishes. But this sisorid catfish from the Indus River drainage of Pakistan is actually quite slim. In fact, the authors describe it as “slim-bodied” and “small-sized.” What were Mirza & Awan thinking?

Diaphus brachycephalus Tåning 1928 — The Shorthead Lanternfish (Myctophidae) occurs circumglobally in tropical and temperate seas (but not the eastern Pacific). Its common name mirrors it scientific: brachys, latinized Greek for short, and cephalus, latinized Greek for head. But the fish’s head is actually quite large relative to its standard length (34.8%). In fact, based on my analysis of head and standard-length measurements, D. brachycephalus has either the largest or second-largest head of the 14 Diaphus species Danish ichthyologist Åge Vedel Tåning (1890–1958) mentioned in his paper (ranging from 27.0–35.0%). So what was Tåning thinking?

Hypoplectrus chlorurus (Cuvier 1828) — The Yellowtail Hamlet (Serranidae) occurs in the Western Atlantic from Texas south to Venezuela, including the western and southern Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea. Its common name refers to its bright yellow tail. Cuvier mentioned the yellow tail in his description (“caudale jaune”). In fact, it’s the fish’s most obvious and distinguishing feature. And yet he named it chlorurus, a combination of the Greek chlōrós (χλωρός), green, and ourá (Gr. οὐρά), tail. What was Cuvier thinking?

17 April

17 April

Rosario LaCorte (1929–2024)

On April 8, aquarist Rosario La Corte died quietly in his home surrounded by family. “With his passing,” wrote fellow aquarist Joseph Ferdenzi, “the aquarium hobby lost one of the greatest aquarists of this generation or any generation. It truly represents the end of an era that none of us will ever see again.”

In the 1950s, Rosario became one of the few aquarists to spawn the Neon Tetra Paracheirodon innesi. This made him famous in the aquarium world, leading to countless speaking engagements at aquarium clubs and conventions. He spawned many other fishes as well, many for the first time. Hobbyists from all over the world visited his fish house, a converted two-car garage. One such visitor was ichthyologist Stanley Weitzman (1927–2017) of the Smithsonian Institution. They became close friends. In fact, making friends and forging lifelong friendships seems to have been a hallmark of Rosario’s life. He went on numerous collecting trips to South America, where he acquired species never before seen in the aquarium hobby. Two of these species, also new to science, were named in his honor:

Nematobrycon lacortei. Source: https://plantedaquaria.ca

Nematobrycon lacortei Weitzman & Fink 1971 — The Rainbow Tetra of Colombia, named in honor of Rosario La Corte for his “long interest in characoids” (he also donated specimens to Weitzman from his fish-breeding operation)

Maratecoara lacortei (Lazara 1991) — An annual killifish from Estado do Goiás, Brazil, named in honor of Rosario LaCorte, who discovered this killifish with fish trader Luis de Camargo Costa and provided photographs

I could write more about Rosario’s life and contributions to the aquarium hobby, but I would just be repeating what his friend Joseph Ferdenzi said in this well-illustrated remembrance.

I recommend Rosario’s delightful memoir, An Aquarist’s Journey. What’s clear is that Rosario was fully committed to everything in his life: his fishes, his family, his country, his faith, his fellow aquarists, and to just being a great human being.

10 April

One letter makes a difference (again)

In previous NOTWs, I’ve been amused with names that would be homonyms — with the senior name replacing the junior — if not for minor differences in their spelling:

Labiobarbus and Labeobarbus

Barbodes and Barboides

Symphurus plagiusa and Symphurus plagusia

Neolamprologus leleupi and Neolamprologus leloupi

Here are two more examples, both made possible by recent taxonomic revisions in which two old synonyms were dusted off and revalidated.

Thryssa purava (Hamilton 1822) and Thryssa porava Bleeker 1849

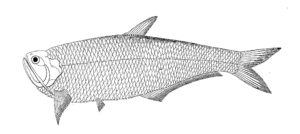

“Peddah Poorawah” from: Russell, P. 1803. Descriptions and figures of two hundred fishes: collected at Vizagapatam on the coast of Coromandel. London, in 2 vols. v. 1–2: i–vii + 78 pp. + 85 pp., 197 pls.

In 1822, Scottish physician-naturalist Francis Hamilton-Buchanan (1762–1829) published An Account of the Fishes Found in the River Ganges and its Branches, the first comprehensive study of Indian fishes. Among the 271 species of fishes Hamilton proposed in the monograph is Clupea (now Thryssa) purava, an anchovy from the Ganges estuaries. He derived the specific name from Peddah Poorawah (“Great Purava”), a local Indian name for anchovies or other herring-like fishes reported (but not scientifically named) in an earlier publication, Descriptions and Figures of Two Hundred fishes; Collected at Vizagapatam on the Coast of Coromandel (1803) by Scottish surgeon-naturalist Patrick Russell (1726–1805).

Twenty-seven years later, Dutch army surgeon and ichthyologist Pieter Bleeker (1819–1878) described an anchovy from the Madura Straits of Indonesia. It is not clear whether Bleeker at the time was familiar with (or had access to) Hamilton’s 1822 work. But he was familiar with Russell’s, because he said that Peddah Poorawah inspired the name Thryssa porava. Note that Bleeker spelled the name with an “o” rather than the “u” as in Hamilton’s purava.

Bleeker’s Thryssa porava had been considered a junior synonym of Thryssa mystax (Bloch & Schneider 1801) until it was revalidated by Hata and Lavoué (as Thrissina porava) earlier this year. Although two species in the same genus cannot have the same specific name — and although purava and porava are derived from the same word and mean the same thing — the one-letter difference in their spellings is all it takes to avoid homonymy.

Pseudambassis Bleeker 1874 and Pseudoambassis Castelnau 1878

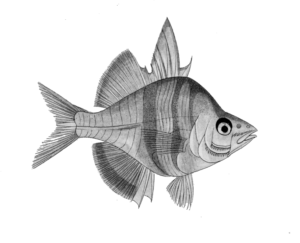

Chanda lala, type species of Pseudambassis. From: Hamilton, F. 1822. An account of the fishes found in the river Ganges and its branches. Edinburgh & London. I–vii + 1–405, Pls. 1-39.

Bleeker is also involved in this case of near homonymy, but this time his name came first.

Pseudo– is a common prefix in both generic and specific names. It is derived from the Greek pseúdēs (ψεύδης), meaning false, and is usually employed to denote a taxon that could easily be mistaken for another. Ambassis Cuvier 1828 is a genus of Asiatic glassfishes or glass perchlets, noted for their transparent or semi-transparent bodies. (See NOTW 21 March 2018 for more on this etymologically interesting name.) Pseudambassis, proposed by Bleeker in 1874, therefore means “false Ambassis,” i.e., although this genus may superficially resemble Ambassis, such an appearance is false. Note that Bleeker did not include the “o” in “pseudo-.”

Four years later, French naturalist Francis de Laporte de Castelnau (1810–1880) came up with the same name while studying the glass perchlets of Australia. Castelnau, exploring in Terra Australis, probably had not seen Bleeker’s account, published in the Netherlands. Castelnau said his Pseudoambassis (note spelling with the “o” that Bleeker did not include) differed from Ambassis in lacking a recumbent pre-dorsal spine. Australian ichthyologist Gilbert Percy Whitley (1903–1975) and his colleague Tom Iredale (1880–1972), incorrectly believing Pseudoambassis to be preoccupied by Pseudambassis, renamed it Blandowskiella in 1932. Subsequent ichthyologists sunk both Pseudoambassis and Blandowskiella into the synonymy of Ambassis.

Last September, a team of researchers led by Siti Zafirah Ghazali of Universiti Malaysia Terengganu studied the phylogeny and biogeography of the family Ambassidae. They proposed a number of taxonomic changes, including the revalidation of Castelnau’s Pseudoambassis to include five Australian and New Guinea species formerly in Ambassis (agassizii, agrammus, elongata, jacksoniensis, macleayi).

The subtle difference between Pseudambassis and Pseudoambassis is easy to overlook. I did so the first several times I read Ghazali et al.’s paper. I was confused by their taxonomic changes until I noticed the one-letter difference.

3 April

Tilurus gegenbauri Kölliker 1853

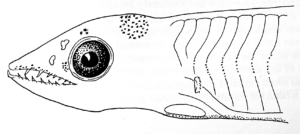

Tilurus head. From: Castle, P. H. J. 1984. Notacanthiformes and Anguilliformes: development. In: H. G. Moser et al., eds. Ontogeny and systematics of fishes. American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists, Special Publication No. 1: 450–459.

One of the early challenges faced by ETYFish was what to do with Species inquirendae. These are species of doubtful identity needing further investigation. (That’s what inquirendae means; it’s Latin for “to be investigated.”) In most cases, they’re older names that predate some of the more restrictive requirements of the ICZN Code. Many are deemed as validly described species with available names but without a type specimen in a museum for taxonomists to examine, compare with related taxa, and perhaps rule on their taxonomic status. In addition, many Species inquirendae are based on larval or juvenile specimens; the adults may await discovery and description or may have already been described. And in some cases, Species inquirendae are superficially described, often utilizing characters shared by one or more related species. Their simply isn’t enough information to accept the species nor place it into synonymy. So Species inquirendae languish in a kind of taxonomic limbo.

Since going online in 2013, The ETYFish Project has provided the etymologies of Species inquirendae and included them in the genus and species counts on the Table of Contents page. My rationale for including them is two-fold. First, I think it’s better to over- rather than under-represent diversity. No one’s written to us complaining that we have too many names in the database! But readers do occasionally let me know when a name is missing. And second, since Species inquirendae are “pending,” it’s useful to include their etymologies just in case new research reveals they warrant recognition. Such entries clearly indicate their “Sp. inq.” status and that their inclusion is provisional. (Likewise, I will delete Species inquirendae if new research reveals they are synonyms.)

Since many taxonomic databases, including Eschmeyer’s Catalog of Fishes, do not count Species inquirendae as “valid” species, I will begin isolating them in our Table of Contents counts in the not-too-distant future.

All of which brings us to a Species inquirenda that has intrigued me since I began investigating fish names in 2009 — a fish that, as far as I can tell, has not been mentioned in an ichthyological publication since 1993: Tilurus gegenbauri.

Tilurus gegenbauri was described as both a new genus and species of leptocephalus (larval eel) by Swiss embryologist and histologist Rudolf Albert von Kölliker (1817–1905) in 1853. The holotype (now lost) was captured in the Mediterranean Sea off Messina, Sicily, Italy. “Circumstantial evidence” published by Smithsonian eel expert David G. Smith in 1989 suggests that the fish is not a true eel (Anguilliformes), but a deep-sea spiny eel (Notacanthiformes, Notacanthidae).

The generic name Tilurus is a combination of tílos (Gr. τίλος), anything plucked, shred or fiber, and ourá (Gr. οὐρά), tail, referring to its tail terminating in a thread. Kölliker named the fish in honor of German comparative anatomist Carl (or Karl) Gegenbaur (1826–1903), who collected and/or provided the holotype.

Since only two notacanthids are known to occur in the Mediterranean — Notacanthus bonaparte Risso 1840 and Polyacanthonotus rissoanus (De Filippi & Verany 1857) — it would be easy to hypothesize that Tilurus gegenbauri is the larval form of one of them. If the latter, then both Tilurus and T. gegenbauri would be senior synonyms. Since a specimen labeled as T. gegenbauri is at the Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle (Paris), maybe a molecular analysis can sort it all out. Tilurus specimens are also known from the eastern North Atlantic, Bermuda, and the Gulf Stream off northern Florida, presumably within the range of Polyacanthonotus rissoanus.

Tilurus trichiurus. From: Kaup, J. J. Catalogue of apodal fish in the collection of the British Museum. London. 1–163, Pls. 1–19.

There are no published images of Tilurus gegenbauri, but I have found two that come close. One shows T. trichiurus (Cocco 1829), provisionally treated as a congeneric leptocephalus. The other is a sketch of a typical Tilurus head, showing its diagnostic short snout and round eye.

For now, the name Tilurus gegenbauri — both species and genus — remain a convenient label for an otherwise unidentifiable larval fish.

27 March

Amen fo eth Kwee

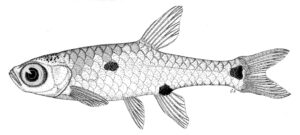

Boraras micros, paratype, 11.2 mm SL. Illustration by Chavalit Vidthayanon From: Kottelat, M. and C. Vidthayanon. 1993. Boraras micros, a new genus and species of minute freshwater fish from Thailand (Teleostei: Cyprinidae). Ichthyological Exploration of Freshwaters 4 (2): 161–176.

Boraras Kottelat & Vidthayanon 1993 The name of this genus of minute freshwater fishes (Danionidae) from Southeast Asia is an anagram of the closely related genus Rasbora, which differ by their reversed ratio of abdominal and caudal vertebrae.

Ricola Isbrücker & Nijssen 1978 Ricola macrops, a loricariid catfish from Argentina and Uruguay, is the only member of its genus. Its name is an anagram of the Latin lorica, a leather cuirass (referring to bony plates on back and sides), and the root of Loricaria, with which this genus is “very similar” in all external characters except for barbel structure and shape and number of teeth.

Polymetme thaeocoryla Parin & Borodulina 1990 The name of this bioluminescent “lightfish” (Phosichthyidae) from the northeast Atlantic Ocean is anagram of the specific name of Polymetma corythaeola, its closest relative.

Kumba Marshall 1973 In 1973, British ichthyologist N.B. Marshall named a new genus of grenadiers or rattails (Macrouridae) after the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom (MBAUK), whose research vessel Sarsia dredged the type species. But “mbauk” or “mbaotuk” are extremely difficult to pronounce. Marshall solved the problem by playfully rearranging the acronym to form “Kumba.”

Erotelis Poey 1860 The genus Eleotris includes 27 species of spiny-cheek sleepers (Eleotridae) from tropical and subtropical ocean waters around the world. The closely related genus Erotelis, an anagram of Eleotris, includes four closely related species from fresh, marine, and brackish coastal waters of North and South America.

Aetapcus maculatus at Popes Eye, Port Phillip, Victoria, Australia. Photo by Rick Stuart-Smith / Reef Life Survey. Courtesy: Wikipedia.

Aetapcus Scott 1936 The Warty Prowfish Aetapcus maculatus, endemic to coastal waters of southern Australia, is the only member of its genus. Australian ichthyologist E. O. G. Scott proposed Aetapcus as a subgenus of Pataecus in which the snout inclines backward instead of forward. It has since been elevated to full genus. Aetapcus is an anagram of Pataecus.

Culaea Whitley 1950 Culaea is a near anagram of Eucalia Jordan 1876 (missing the “i”), the original name for this stickleback genus but preoccupied in butterflies. The original name translates as eu-, a Greek prefix (well, good or very), and calia (Neo-Latin from the Greek kalia), bird nest, referring to the nest-building habits of sticklebacks.

See the 2 August 2017 Mena fo het Ewek for four anagrammatic toadfish names coined by South African ichthyologist J. L. B. Smith.

20 March

John D. McPhail (1934–2023)

Bryozoichthys marjorius. From: McPhail, J. D. 1970. A new species of prickleback, Bryozoichthys marjorius (Chirolophinae), from the eastern North Pacific. Journal of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada 27 (12): 2362–2365.

I recently learned that Canadian ichthyologist John D. McPhail passed away last summer. He was an expert on the fishes of northwestern North America and, most famously, the difficult taxonomy of benthic and limnetic sticklebacks (Gasterosteus aculeatus) of southwestern British Columbia. He made these sticklebacks a model system in which to test two fundamental questions in biology: What exactly is a “species,” and how do they arise?

Two of his books grace my bookshelf:

Freshwater Fishes of Northwestern Canada and Alaska, authored with Casimir C. Lindsey, was published in 1970. Although 44 years old and quite out-of-date, it’s still a fascinating read, if only for the appreciation you gain of how difficult it must be to explore the waters of the coldest, most desolate, and least-populated two million square miles in North America. McPhail and Lindsey repeatedly express just how little science knows about the fishes of the “deep North,” as in this passage on the Deepwater Sculpin Myoxocephalus thompsoni: “We have twice kept captive deepwater sculpins in aquaria for 2 weeks before they died; during this time they were timid and passive, refusing even live food. How this little fish lives, what its abundance is, and what role it plays in the ecosystem of deep northern lakes, are literally deep and dark secrets” (p. 323).

Thirty-seven years later, McPhail wrote The Freshwater Fishes of British Columbia (2007), illustrated by his daughter Diana. It is one of the best “Fishes of …” books ever.

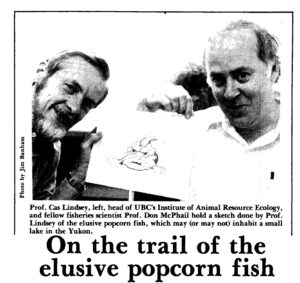

Lead-in of newspaper article. From: Banham, J. (Editor). 1980. On the trail of the elusive popcorn fish. UBC Rep. 26(16): 2.

In cryptozoology circles, McPhail (along with Lindsey) is noted for his efforts to confirm the existence of the elusive “Popcorn Fish.” So named for the large popcorn-like bumps on its head, the fish was first reported in 1953 from a small lake in a remote, isolated region of the Yukon. Knowing that a number of unique insects, mosses and alpine flowers in that region survived the ice age 10,000 years ago, McPhail and Lindsey believed there was precedent that the Popcorn Fish could be real. They did not find any specimens, but they did convince authorities to officially name the unnamed lake Popcornfish Lake. So, in a way, the Popcorn Fish lives on.

As for fishes that actually exist, McPhail described two new species, both from Alaska. In 1965, he described the Smallmouth Ronquil Bathymaster leurolepis, named for its smooth and embedded scales (from the Greek leurós, smooth, and lepís, scale). In 1970, he named the Pearly Prickleback Bryozoichthys marjorius. The specific epithet is both a variant of the Latin margarita, pearl, referring to its distinctive pearly-white coloration, and a matronym in honor of McPhail’s wife Marjorie.

13 March

Paul Humann (1937–2024)

Paul Humann with a Goliath Grouper Epinephelus itajara. From: https://divernet.com

Diver, underwater photographer, author, and conservationist Paul Humann passed away at the age of 86 on 5 February at his home in Davie, Florida. His Reef ID Guides of Florida, the Caribbean and Bahamas, are familiar to many scuba divers and marine biologists.

Two fishes are named in honor of Humann. In 2010, eel expert John C. McCosker described Ophichthus humanni, a snake eel from Vanuatu, crediting Humann for “generously” aiding ichthyologists with his photographs and observations. Two years later, Gerald R. Allen and Mark V. Erdmann described Cirrhilabrus humanni, a fairy wrasse from Indonesia. Humann, along with fellow photographer-authors Ned and Anna DeLoach, were the first to sight this wrasse. Allen and Erdmann said, “Paul has been an important contributor to our knowledge of reef fishes through the publications of his company New World Publications, Inc. of Jacksonville, Florida.”

An ornate cup coral, Coenocyathus humanni, from the tropical Western Atlantic, bears his name as well.

Humann grew up far from the ocean, in Wichita, Kansas. He graduated in biology at Wichita State University and studied law at Washburn Law School in 1964. During law school, he learned how to dive, take underwater photos, and fly a plane. (When did he have time to study?) After seven years working for a large law firm, he was made a partner.

In 1971, Humann quit the law firm to become owner and captain of Cayman Diver, a liveaboard dive-cruiser. He used his pilot’s license to scout potential reef-sites. While diving with his customers, Humann began photographing Caribbean marine life. In 1980, he moved to Florida and began publishing his photographs as ID guides for divers. In 1988, he joined Ned DeLoach to become co-editor of Ocean Realm magazine. This was the beginning of a long business partnership, as they published a total of 14 books starting Reef Fish Identification, Reef Creature Identification and Reef Coral Identification – Florida, Caribbean, Bahamas.

Humann and DeLoach went on to start the Florida-based REEF Reef Environmental Education Foundation in 1990. Its aim is to help protect ocean biodiversity through citizen-science, education and partnership with the scientific community. REEF’s volunteer divers and snorkelers have compiled what is said to be the world’s biggest fish-sighting database.

Humann was inducted into the International Scuba Diving Hall of Fame in 2007.

6 March

Sturisoma lyra (Regan 1904)

English ichthyologist Charles Tate Regan (1878–1943) of the Natural History Museum (London) described 34 new species in his 1904 monograph on loricarioid catfishes. All but six of the names he proposed remain valid and in use today. Regan did not provide etymologies in his descriptions, but in most cases he provided enough information to tease out a reasonable explanation for the name. For one species, Oxyloricaria (now Sturisoma) lyra, he did not.

English ichthyologist Charles Tate Regan (1878–1943) of the Natural History Museum (London) described 34 new species in his 1904 monograph on loricarioid catfishes. All but six of the names he proposed remain valid and in use today. Regan did not provide etymologies in his descriptions, but in most cases he provided enough information to tease out a reasonable explanation for the name. For one species, Oxyloricaria (now Sturisoma) lyra, he did not.

Here is the complete description:

Closely allied to the preceding species [Oxyloricaria robusta, now Sturisoma barbatum], but with a smaller eye (diameter 9-11 times in the length of head), more numerous scutes, 36-37 in a longitudinal series, 20-21-1-16, the anal plate bordered anteriorly by 3 which are again bordered by 3 or 4, instead of by 5, and the body more slender, the width at the level of the last anal ray 4-5 times in the distance from the latter to the caudal. Olivaceous, dorsal and pectoral with dark spots on the rays; anal sometimes with a blackish tip; lower lobe of caudal with an oblong blackish patch.

Total length 250 mm.

Ten specimens from the Rio Jurua [middle Amazon River basin, Brazil], collected by Dr. Bach, had been referred by Boulenger to L. rostrata, in his account of the Bach Collection.

Regan named the species lyra, Latin for lyre, a small U-shaped, hand-held harp used especially in ancient Greece (shown here). Regan did not mention a lyre nor anything lyre-like in his description, so the meaning of the name remained a mystery to me for many years. Recently, however, I had occasion to revisit the name, as I often do with “cold case” etymologies I had not solved. When I compared Regan’s written description with the illustration created by the Natural History Museum’s in-house lithographer J. Green, I noticed a detail I had overlooked:

Sturisoma lyra. From: Regan, C. T. 1904. A monograph of the fishes of the family Loricariidae. Transactions of the Zoological Society of London 17 (pt 3, no. 1): 191–350, Pls. 9–21.

Green had artfully arranged the catfish’s long caudal-fin filaments*, both extending away from the tail and then curling back towards it. With some imagination, you can see that the shape of the tail resembles the shape of a lyre.

Is this what Regan had in mind when he named the fish? That’s impossible to say for sure. But he gave it an elegant-sounding name. And the artistic license Green took in rendering the caudal fin is an elegant touch.

* Filaments such as those of Sturisoma lyra develop in various Loricariidae, usually subfamily Loricariinae, but also in Hypostomus nematopterus (subfamily Hypostominae) as fragile extensions of some fin rays. They probably play a role in matters of taste and touch (Isaäc J. H. Isbrücker, pers. comm.). They are recorded in many descriptions but it appears no one has published a special study about them.

28 February

Cyprinella analostana Girard 1859

This Saturday, I am giving a talk about The ETYFish Project to the Potomac Valley Aquarium Society in Fairfax, Virginia, USA. “Potomac Valley” refers, of course, to the Potomac River, which flows for 652 km from the Potomac Highlands of West Virginia into the Chesapeake Bay of Maryland. More famously, the river forms part of the border between Washington, D.C. and Virginia. This prompted me to wonder:

Has a fish been named for the Potomac River?

The answer is no. But one comes very close.

Cyprinella analostana. Courtesy NCFishes.com

In 1859, French ichthyologist Charles Girard (1822–1895) described the Satinfin Shiner Cyprinella analostana from Rock Creek, a tributary of the Potomac River that flows through Washington, D.C. Girard was quite familiar with the area. He worked at the Smithsonian Institution and earned his M.D. from Georgetown University, just a few blocks away from the river. Girard named the shiner for Analostan Island, a 358,000 m2 island in the middle of the Potomac almost directly across from Rock Creek. “Analostan” is derived from the indigenous Anacostan (or Nacotchtanck) people who once lived there.

During the American Civil War (during which Girard served as a surgeon for the Confederates), the island was used as a training camp for the United States Colored Troops, primarily comprised of African Americans. In addition, the island also served as a refugee camp for freed Black people who flocked to Washington, D.C., following emancipation. Despite the U.S. government’s presumably good intentions, the camp was poorly managed, becoming overcrowded with 1,200 starving, sick people who lived, per one report, in “disease-ridden squalor,” lacking the “bare necessities of life.”

Today, the island is known as Theodore Roosevelt Island, maintained by the U.S. government as a natural park. No cars or bicycles are permitted on the island, which is reached by a footbridge from Arlington, Virginia, on the western bank of the Potomac.

The Satinfin Shiner is well known to me, as it is a common inhabitant of the streams near where I live. I’ve spent many hours snorkeling with Satinfins. The key is to snorkel facing downstream and to let the Satinfins swim upstream towards your mask, where they feed on whatever food particles you dislodge from the substrate. The “Satinfin” monicker refers to the milky-white border surrounding all fins on nuptial males.

All Cyprinella shiners (30 described species) are noteworthy for their novel reproductive strategy. To borrow a phrase from the late Phil Cochran, they’re fishes that spawn in trees. Literally.

Cyprinella deposit their eggs in crevices in submerged logs, loose bark on fallen trees, tree roots, and other woody debris, or in the cracks between rocks and boulders. Crevice spawning protects the eggs from a number of hazards, including predation by other fishes, abrasion by drifting items, being swept away by strong currents, smothering in silty or muddy bottoms, and direct sunlight.

In addition to crevice spawning, Cyprinella exhibit another reproductive behavior that may be unique to the genus—mock solo spawning, or the solo run. In mock solo spawning, dominant nuptial male Cyprinella go through the motions of spawning—cruising over crevices, vibrating, undulating, holding their fins erect—before actual spawning occurs. Three possibilities may explain this behavior. Males could be testing the suitability of the crevice and/or checking for appropriate water velocity. They could be signaling to the female, “Yes, this is the place!” And they could be ejaculating sperm into the crevice before the female arrives.

When they’re not mock spawning, male Cyprinella are highly territorial. They chase, bite, ram, head-butt, and may even grab rival males by a fin and “escort” them away from the spawning site. Females, meanwhile, hang close by in a group and watch the goings on. Occasionally a male will swim up to a female and encourage her to follow him back to the nest. Once a female makes up her mind to spawn, courtship can last for seconds or even hours. When she’s finally ready, the female “sprays” her eggs into the crevice with great accuracy, sometimes from as far as 5 cm away. Should any eggs miss or fall out of the crevice, the male circles back and eats them.

For land-based fishwatchers, a shoal of 25 or so male Cyprinella in full breeding regalia is a glorious sight indeed. Look for flashes of white in areas where trees have fallen into the water. If you can snorkel towards a Cyprinella nest, even better. Keep still and they won’t notice you’re there.

Unlike most other minnows, in which the females deposit most or all of their eggs at once, Cyprinella are “fractional spawners,” so called because females deposit only a fraction of their eggs during each spawning act. As a result, the Cyprinella breeding season can last from the spring through summer, and even into autumn in some areas. Fractional spawning is said to increase reproductive potential by reducing the number of larvae that compete for food and space at any one time. It’s also a wise strategy for fishes that are choosy about where they spawn; since the number of appropriate crevices in any given stream may be limited, fractional spawning allows Cyprinella to reuse the same sites week after week after week.

21 February

Fishes named after inventors

Electrophorus voltai de Santana, Wosiacki, Crampton, Sabaj, Dillman, Castro e Castro, Bastos & Vari 2019

This electric eel is named in honor of Alessandro Giuseppe Antonio Anastasio Volta (1745–1827), the inventor of the electric battery and for whom the “volt” is named. With a discharge of 860 V, this eel is the strongest living bioelectricity generator known.

Hyphessobrycon peugeoti, holotype, male, 38.5 mm SL. From: Ingenito, L. F. S., F. C. T. Lima and P. A. Buckup. 2013. A new species of Hyphessobrycon Durbin (Characiformes: Characidae) form the rio Juruena basin, central Brazil, with notes on H. loweae Costa & Géry. Neotropical Ichthyology 11 (1): 33–44.

Hyphessobrycon peugeoti Ingenito, Lima & Buckup 2013

This tetra is named in honor of the Peugeot family of France (better known for their cars), who invented the pepper grinder in 1842. Earlier versions of pepper mills were based on a mortar-and-pestle design. Peugeot’s grinder used case-hardened steel to crack the peppercorns before the actual grinding, a less labor-intensive process. In addition, the grooves on the Peugeot mechanism were individually cut into the metal, making them very durable. According to the ichthyologists who described and named this tetra, the Peugeot family’s contemporary manufacturing business led to the establishment of a carbon sink reforestation project in the fazenda São Nicolau, in central Brazil, which led to the discovery of this species. They still make pepper mills, very expensive ones at that.

Pandaka lidwilli (McCulloch 1917)

This dwarf (15.25 mm) goby occurs in brackish and salt water in the mouths of rivers and maritime zones in Japan, Australia, and Papua New Guinea. It’s named in honor of Mark C. Lidwill (1878-1969), an English-born Australian anesthesiologist and cardiologist. With physicist Edgar H. Booth, he invented the pacemaker in 1926. When not saving lives, Lidwill was also an avid rod-and-reel saltwater angler. He observed this minute goby “while in the quest of somewhat larger game” and brought it to McCulloch’s attention.

Grammonus claudei. © Micky Charteris. From: Robertson, D. R. and J. Van Tassell. 2023. Shorefishes of the Greater Caribbean: online information system. Version 3.0 Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Balboa, Panamá. https://biogeodb.stri.si.edu/caribbean

Grammonus claudei (Torre y Huerta 1930)

As its common name indicates, the Reef-cave Brotula lives in reefs and caves along the shorelines of Cuba, Bermuda and the Bahamas. It’s named in honor of French engineer Georges Claude (1870–1960), who inadvertently discovered it in Matanzas Bay, Cuba, when pumping cool seawater up from the depths to convert into electricity via a process called “ocean thermal energy conversion.” Georges Claude — at one time called the “Edison of France” — was also the inventor of neon lighting. In 1945, he was imprisoned for five years for collaborating with Germany during World War II.

Gramma linki. © Scott Michael. From: Robertson, D. R. and J. Van Tassell. 2023. Shorefishes of the Greater Caribbean: online information system. Version 3.0 Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Balboa, Panamá. https://biogeodb.stri.si.edu/caribbean

Gramma linki Starck & Colin 1978

Edwin Link (1904–1981) was an American entrepreneur and pioneer in aviation, underwater archaeology, and submersibles. One of his submersibles, Deep Diver, was the first small submersible designed for “lockout diving,” allowing divers to leave and enter the craft while underwater. Deep Diver was used to collect the holotype of the Yellowcheek Basslet off Cozumel Island, Mexico, in the Caribbean Sea. The authors said Link’s “imaginative developments in undersea technology and generous support of marine science have made untouched realms of the sea accessible.” Among Link’s 27 patents is one for the invention of the flight simulator in the 1920s.

14 February

Happy Valentine’s Day!

Today is Valentine’s Day. Here is a quartet of love- and heart-themed names from the realm of fishes.

Pseudoscopelus cordilluminatus Melo 2010 Pseudoscopelus (Chiasmodontidae) is a genus of meso- and bathypelagic fishes with a worldwide distribution. Like many deep-sea fishes, they possess luminous glandular organs called photophores. Ichthyologists often use the shapes and patterns of these photophores to distinguish between otherwise similar-looking species. This species, from the Indian Ocean and eastern South Atlantic, is distinguished in part by the patch of photophores on its body just above the anal fin. The author, Marcelo R. S. Melo, described this patch as heart-shaped and named it accordingly: a combination of the Latin cordis, of the heart, and illuminatus, full of light.

Atherina boyeri, photographed in Sardinia, Italy, by Roberto Pillon. Source: Wikipedia.

Atherina boyeri Risso 1810 France has a long history of art, literature and culture that celebrates love and romance. Even a baitfish, the Big-scale Sand Smelt, has a love-themed scientific name. French naturalist Antoine Risso (1777–1845) described the species from his hometown of Nice, France, and wanted to honor a fellow Niçard with its epithet. He chose Guillaume Boyer, a Medieval poet, naturalist and mathematician. According to Risso, Boyer’s “love poems were sung by all the troubadours of the 13th century” (translation). La musique c’est l’amour!

Many ichthyologists have demonstrated how much they love their spouses by naming fishes after them. If the next two epithets are any indication, being the wife of an ichthyologist requires a certain amount of patience.

Bryconamericus yokiae Román-Valencia 2003 Colombian ichthyologist César Román-Valencia named this characin from the Salado River of Venezuela in honor of his wife Yoki. He described as “La bruja de mis suenõs” (“the witch of my dreams”) and thanked her “for her sleepless nights and patience with a husband in love with little fishes.” A Spanish speaker informed me that “La bruja de mis suenõs” is a term of endearment, akin to a “bewitching woman.”

Nothobranchius ditte, paratype, male, 42.4 mm SL. From: Nagy, B. 2018. Nothobranchius ditte, a new species of annual killifish from the Lake Mweru basin in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Teleostei: Nothobranchiidae). Ichthyological Exploration of Freshwaters 28 (2): 115–134.

Nothobranchius ditte Nagy 2018 Some ichthyologists are also aquarium hobbyists. Killifish taxonomist Béla Nagy apparently has lots of tanks at home. In 2018, Nagy named this annual killifish from ephemeral swamps in the Democratic Republic of the Congo for his “beloved” wife Edit Csikós, nicknamed “Ditte.” He thanked her for her “patience during all the time I am away for collecting fishes and also for the care of keeping all the fish alive during my absences.”

A wife who takes care of your aquariums — now that’s love!

For more love-inspired fish names, see the “Name of the Week” for Valentine’s Day, 14 February 2018.

7 February

7 February

Shakespearean fishes

Some taxonomists like to show off their learning by naming taxa after characters from the plays of William Shakespeare. Ichthyologists are no exception. Here are fish names inspired by the Bard of Avon.

Iago Compagno & Springer 1971 This small genus (three species) of houndsharks (Triakidae: Galeorhininae) occurs in deeper waters in the Indian and Western Pacific oceans. The genus was named for Iago, a villain in Shakespeare’s Othello, referring to how the classification of the type species, I. omanensis, had been a “troublemaker for systematists and hence a kind of villain.”

First-published illustration of Malvoliophis pinguis. From: Günther, A. 1873. Reptiles and fishes of the South Sea Islands. In: Brenchley, J. L., Jottings during the cruise of H. M. S. Curaçao among the South Sea Islands in 1865. 1–487, Pls. 1–59.

Malvoliophis Whitley 1934 This monotypic genus of snake eel (Ophichthidae: Ophichthinae) occurs in the Western Pacific. Gilbert Whitley (1903–1975) did not explain the meaning of the name (he often did not). In 1977, eel expert John E. McCosker, citing a personal communication with Whitley, reported that the genus is named for Malvolio, Lady Olivia’s steward in Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night, alluding to the banded coloration of M. pinguis, suggestive of the cross-gartered legs and yellow socks worn by that character. (The second part of the name, ophis, Greek for serpent, is a conventional termination for the generic names of snake eels, referring to their snake-like shape.)

Sundadanio atomus Conway, Kottelat & Tan 2011 Although not directly inspired by Shakespeare, the authors of this danionid from peat-swamp forests of Indonesia mention the Bard in their etymology. Atomus is Latin for an indivisible particle, referring to the fish’s small size (up to 15.7 mm SL). The authors say the name also alludes to the Middle English atomy, a diminutive fairy creature or sprite, a team of which drew Queen Mab’s carriage in Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet.

Priocharax ariel Weitzman & Vari 1987 This name of this diminutive characin (up to 15.1 mm SL) is derived from the Greek aeriios, meaning aerial (existing, happening or operating in the air), which Shakespeare applied to the name of a spirit in The Tempest. This fish’s small size and translucent coloration in life reminded Weitzman and Vari of Shakespeare’s airy spirit.

Ophidion antipholus, O. dromio and O. puck Lea & Robins 2003 Lea and Robins named two of these cusk-eels (Ophidiidae) after the brothers Antipholus and Dromio from Shakespeare’s The Comedy of Errors. The brothers’ identities are confused throughout the play. Likewise, these two species had been widely and incorrectly reported as O. beani (a junior synonym of O. holbrooki). The third species, O. puck, is named for Puck, a “tricky fairy” in the service of King Oberon in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. The authors say the choice of three Shakespearean names indicates that these species are “part of a larger story,” but they do not explain what this story might be.

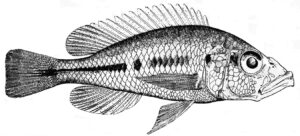

Haplochromis cassius. Illustration by Martien J. P. van Oijen. From: Greenwood, P. H. and C. D. N. Barel. 1978. A revision of the Lake Victoria Haplochromis species (Pisces, Cichlidae), Part VIII. Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History) Zoology 33 (2): 141–192.

Haplochromis cassius Greenwood & Barel 1978 This African cichlid from Lake Victoria has, in my opinion, the coolest Shakespearean name among fishes. It’s from Julius Caesar (Act I, Scene II), “Yond Cassius has a lean and hungry look.” The authors did not explain their selection of the name, but they mention that the fish has a “predatory” appearance. Their illustration (shown here) shows a “lean and hungry”-looking fish indeed.

31 January

In honor of Professor Súper O

Sturisoma defranciscoi Londoño-Burbano & Britto 2023 is a recently described species of loricariid catfish known from the upper Amazon River basin of Colombia and the upper Solimões River drainage of Brazil. Its name, an eponym, honors someone you wouldn’t normally associate with fishes: Martín Guillermo de Francisco (b. 1966), a Colombian television announcer, actor, sports journalist, and creator (and I assume voice) of Professor Súper O, an animated Columbian television series first broadcast in 2006.

Sturisoma defranciscoi Londoño-Burbano & Britto 2023 is a recently described species of loricariid catfish known from the upper Amazon River basin of Colombia and the upper Solimões River drainage of Brazil. Its name, an eponym, honors someone you wouldn’t normally associate with fishes: Martín Guillermo de Francisco (b. 1966), a Colombian television announcer, actor, sports journalist, and creator (and I assume voice) of Professor Súper O, an animated Columbian television series first broadcast in 2006.

Professor Súper O is a superhero who corrects people who make grammatical and linguistic mistakes.

Sturisoma defranciscoi, holotype, 228.3 mm SL. From: Londoño-Burbano, A. and M. R. Britto. 2023. Taxonomic revision of Sturisoma Swainson, 1838 (Loricariidae: Loricariinae), with descriptions of four new species. Journal of Fish Biology Early view: [1-53].

I emailed the first author asking if Professor Super O played an important part in the authors’ younger, formative years, but I have not received a reply.

Other TV personalities honored in the names of fishes include naturalist David F. Attenborough, Nothobranchius attenboroughi Nagy, Watters & Bellstedt 2020, a seasonal killifish from Tanzania; writer and explorer Anthony Smith Eidinemacheilus smithi (Greenwood 1976), a blind cave loach (see NOTW, 4 Jan. 2023); and TV math teacher William Smith, Coryogalops william (Smith 1948), a goby from the Western Indian Ocean, described by his father, South African ichthyologist J. L. B. Smith (see NOTW, 22 May 2019).

24 January

Pez grasso, the Greasefish: Rhizosomichthys totae (Miles 1942)

Rhizosomichthys totae, holotype. © D & R Lalkaka. From: Planet Catfish.

Rhizosomichthys totae (Trichomycteridae) is one of the most unusual catfishes in the world. Its distinctive feature is the presence of six or seven rings of adipose tissue that encircle its trunk, plus two large pads of adipose tissue on top of its head. Known only from Lake Tota, a high-altitude lake situated in the mountains outside Bogota, Colombia’s capital city, only 10 specimens are known. Last seen in 1957, the Greasefish is thought to be extinct.

Interestingly, for such a distinctively fatty fish, its generic name, Rhizosomichthys, is something of a riddle. But I believe I figured it out.

English naturalist Cecil Miles, who introduced rainbow trout to Colombia, initially described the catfish as Pygidium totae in 1942. (Pygidium, diminutive of the Latin pyga, rump, from the Greek pygḗ [πυγή], was then a catch-all name for many trichomycterid catfishes; it is now considered a name of doubtful identity and no longer used.) The specific name, “of Tota,” clearly refers to the lake where it occurred.

Miles suggested that the species deserved its own genus, and even proposed a provisional name “Bathophilus” — bathýs (Gr. βαθύς), deep + phílos (Gr. φίλος), fond of — referring to the deep water (up to 300 m, according to Miles, but other accounts say 65–80m) of the lake where the catfish lived. But Miles hesitated for two reasons: (1) He was not sure whether the name “Bathophilus” had already been proposed for another animal genus. And (2), to quote his words: “although the fatty folds were always present in regular series … there was still a remote possibility that the origin of the folds was pathological.”

Over the next several months, Miles corresponded with other ichthyologists and learned that “Bathophilus” was in fact twice preoccupied, including Bathophilus Giglioli 1882, a genus of barbled dragonfishes (Stomiidae), and was therefore not available. He also learned, through a fish parasitologist — amusingly named Dr. Frederic F. Fish — that there was no histological evidence that the fatty folds were due to tumor or disease. In other words, the adipose tissue was indeed a natural and therefore diagnostic character.

One would think that Miles would propose a generic name that unambiguously referred to the fish’s fatty tissue. After all, Miles mentioned that the locals called the catfish “pez grasso,” or greasefish. He said the rings of fat resembled automobile tires. He reported that the fat was easily combustible, burning like a candle and smelling like butter when lit. In fact, a few years prior, an earthquake had apparently killed large numbers of this catfish, which residents burned to light their homes. And Miles said that the catfish possessed an internal layer of body fat similar to the blubber of whales.

Instead, Miles seemingly ignored all of these fascinating facts about the catfish and named the genus, without any explanation, Rhizosomichthys.

The last part of the name, ichthýs (Gr. ἰχθύς), clearly means fish. The first part of the name can be explained two ways: (1) rhizo-, from rhíza (Gr. ῥίζα), root + sṓma (Gr. σῶμα), body, i.e., “root body fish.” (2) rhízōma (ῥίζωμα), a “mass of roots” or rhizome, a botanical term for a subterranean plant stem that sends out roots and shoots from its nodes, i.e., “rhizome fish.”

Other than a general reference to deep water, Miles did not mention habitat in his two papers about the fish. He did not mention whether it occurred in root wads at the bottom of the lake. But when I googled “rhizome” I came across a number of photos, including turmeric and ginger (shown here) rhizomes. Compare it to a photograph of the holotype shown above.

Other than a general reference to deep water, Miles did not mention habitat in his two papers about the fish. He did not mention whether it occurred in root wads at the bottom of the lake. But when I googled “rhizome” I came across a number of photos, including turmeric and ginger (shown here) rhizomes. Compare it to a photograph of the holotype shown above.

See a resemblance?

Miles likely played a role in the catfish’s extinction. He determined that the cold waters of Lake Tota was perfect for the introduction of rainbow trout. In 1936, 100,000 rainbow trout eggs, imported from North America, were released into the lake. When Miles described the catfish, he wrote (translated from the Spanish): “Of the few specimens obtained, the majority were found in a mutilated state, which is attributed to the activities of rainbow trout planted in the lake by the Ministry of the Economy. It’s possible, therefore, this species, without economic importance, is condemned to extinction.”

Recent efforts to locate Rhizosomichthys totae via environmental DNA (eDNA) have not been successful.

17 January

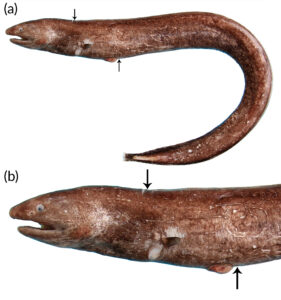

Dysomma intermedium Vo & Ho 2024

Dysomma intermedium, holotype, 525 mm TL. (a) Lateral view. (b) Lateral view of head. Arrows point to dorsal-fin origin (dorsal) and anal-fin origin (ventral). From: Vo, V. Q., H.-C. Ho, H. V. Dao and T. C. Tran. 2024. New species of the eel genera Dysomma and Dysommina from Vietnam, South China Sea (Anguilliformes: Synaphobranchidae). Journal of Fish Biology Early view: 1-12. DOI: 10.1111/jfb.15638

Every year around this time we highlight the first-described new fish species of the New Year. For 2024 it is Dysomma intermedium.

Dysomma intermedium is an arrowtooth eel (Synaphobranchidae, subfamily Ilyophinae) described from off the southeast coast of Vietnam, collected via bottom trawl at 50–80 m. Its specific epithet is Latin for intermediate, referring to the “intermediate status of [its] trunk length and many characters that are shared with other congeners.”

The generic name Dysomma, proposed by British physician-naturalist Alfred William Alcock (1859–1933) in 1889, refers to their eyes, small and covered by thick, semi-transparent membrane. The Greek prefix dys– (δυς-) indicates something negative or unfavorable. The Greek noun ómma (ὄμμα) means eye.

According to Eschmeyer’s Catalog of Fishes, 347 new fish species (241 freshwater, 106 marine/brackish) were described in 2023, well under the average of 406 new species described annually since 2004.

10 January

Hypsolebias lulai Ramos, Nielsen, Abrantes, Lira & Lustosa-Costa 2023

In the 15 years that I’ve been studying fish names, I have not seen this happen: Someone has publicly criticized the name of a new species of fish, calling it “One of the Greatest Naming Errors in Taxonomic History.”

Hypsolebias lulai, male, 50.6 mm. From: Ramos, T. P. A., D. T. B. Nielsen, Y. G. Abrantes, F. O. Lira and S. Y. Lustosa-Costa. 2023. A new species of cloud fish of the genus Hypsolebias from northeast Brazil (Cyprinodontiformes: Rivulidae). Neotropical Ichthyology v. 21 (no. 3): e230068: 1-15.

The fish in question is Hypsolebias lulai, an annual rivulid cloudfish known only from a temporary pool in the rio Trairi basin, Rio Grande do Norte State, Brazil. Like other annual killifishes, species of Hypsolebias are alive only during the rainy season. When their pools dry up, the adults die but their eggs persist in the substrate. The eggs hatch and the species repeat their life cycles when the rains return. Also, as with many other Hypsolebias species, H. lulai is at risk of extinction, in this case specifically due to the small size of its habitat, nearby agriculture, invasive Nile Tilapia Oreochromis niloticus, and hydroelectric dams.

The authors named the new species in honor of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (b. 1946), the current (2023) president of Brazil, “responsible for restoring conservation actions and socio-environmental enhancement and resuming incentives for Brazilian science.”

Any taxon named after a political figure is bound to draw both praise and criticism depending on one’s political preference. Since I do not live in Brazil, nor follow Brazilian politics, I cannot comment on Lula’s presidency. But I do understand that there are deep divisions in Brazilian society, akin to the political polarization in America. And herein lies the source of a pointed criticism of the Hypsolebias lulai name, posted on ResearchGate by one Fabiano Leal, who describes himself as “professional historian and independent researcher, which focuses on the approach of complex adaptive systems as a tool for analyzing historical phenomena.”

Leal argues that naming this fish after Lula plays into the stark political divisions in Brazil, wherein both sides vehemently hate and fear each other. This may be detrimental to the species’ survival in the wild. Leal says that the authors of H. lulai have “simply involved the new taxon in the whirlwind of the polarizing context. In fact, there is a real risk that this particular species will now be associated with a political identity, and an equally extensive risk that this identity will be extended to all rivulids. The problem here is that everything associated with one of the parties involved in this conflict is viewed and considered negatively by the other, becoming an object to be fiercely opposed.”

The name of this species made headlines in Brazil. Leal tracked the online comments. “Most of the negative comments contained derogatory elements towards the species,” he says. None of them mentioned any aspect of the importance of the discovery of a new species, its annual life history, nor its imperiled status. Instead, some comments “attributed to the species those negative attributes they saw in the Brazilian president, resulting in a clear process of personalizing the species, which occurs when a taxon starts to carry the attributes of a personality.”

Leal also worries that “conservation projects relying on government funds may be linked to political, ideological, and partisan actions that imply some degree of threat, whether real or imagined, to the interests of opposition groups. This could lead to a reduction in investments or even the discontinuation of projects.”

Leal goes on to argue that the naming of the cloudfish reflects how universities (including taxonomists who work for these universities) have become a “captive organ of the political-ideological interests of the Brazilian left.” In other words, scientists and academics tend to lean left, so they will see nothing controversial in naming a species after a leftist politician (such as Lula).

I saw something similar with the naming of four American darter species (Percidae) after Jimmy Carter, Bill Clinton, Al Gore and Barack Obama in 2012. Some were okay with the names. Others thought they were a travesty.

Leal concludes by saying that species should not be named after politicians “involved in processes of polarization and social division,” as this can “drag a species into a scenario of ideological dispute that is not in the interest of a field of study like systematic[s], and with the serious potential to reflect on other segments, such as projects seeking to safeguard species from extinction.”

While I fervently support the right of taxonomists to name species any way they wish, I do wince when they honor political figures. I prefer names that bring people together to celebrate the taxon being described. Political epithets tend to pull people apart.

One 20th-century American ichthyologist is reputed to have said this about honoring politicians:

“Give them the streets, but keep them out of our [taxonomic] papers.”

Abudefduf saxatilis swimming inshore at Phil Foster Park, Florida. Source: Wikipedia.

3 January

Abudefduf Forsskål 1775

Fish ecologist Jan Jeffrey Hoover (see 1 July 2015 NOTW) sent me an amusing name-related passage from the 1920 book In Lower Florida Wilds: A Naturalist’s Observations on the Life, Physical Geography, and Geology of the More Tropical Part of the State by Charles Torrey Simpson (1846–1932), an American botanist, malacologist, and conservationist. The passage concerns the genus name of the Sergeant Major Abudefduf saxatilis (Linnaeus 1758), a common inhabitant of the Western Atlantic from North Caroline to the Caribbean Sea.

Abudefduf is one of the oddest “Latin” names of fishes, probably because it’s not Latin. It’s Arabic. It is named for Abu-defduf, the Arabic name for A. sordidus from the Red Sea and Indo-West Pacific. The name is a combination of three elements:

Abu, father (i.e., possessor, or one with), or abū, a prefix particle denoting “an animal having or being like”

def, meaning side

–duf, an intensive plural ending

Roughly translated, Abudefduf means “the one with prominent sides,” presumably referring to the dark crossbands on A. sordidus and related species.

While Abu-defduf no doubt sounded like a normal word throughout the Arab world of the late 18th century, its combination of phonemes likely sounded strange to Charles Torrey Simpson, whose western ears were attuned to Latin and other Romance languages. Here is what he wrote in 1920:

“This little living jewel bears the atrocious scientific name of Abudefduf saxatilis. Anyone who would blight the life and reputation of such a wonderful creature by calling it ‘Abudefduf’ ought to be barred from naming any more of nature’s creations. And its common names of ‘cow pilot’ and ‘sergeant major’ are not much better. We ought to have a society for the prevention of nomenclatural cruelty to animals.”

“Society for the Prevention of Nomenclatural Cruelty to Animals” — I know some biologists who believe such a society should be formed.

Footnote: The common name “cow pilot” refers to its alleged habit of being always found near cowfishes of the genus Ostracion. The common name “sergeant major” refers to its stripes, said to resemble the traditional insignia of the military rank.