NAMES OF THE WEEK from: 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2020 2021 2022 2023 2024 2025

Synchiropus splendidus at the Aquarium-Museum of Liège (Belgium). Photo by Luc Viatour, courtesy of Wikipedia.

25 December

Synchiropus splendidus (Herre 1927)

Today is Christmas. And so we celebrate the brilliant colors of the holiday season by featuring what many have called the most brilliantly colored fish in the world — the Mandarinfish or Mandarin Dragonet, Synchiropus splendidus, of tropical Pacific waters ranging from the Ryuku Islands of Japan south to Australia.

Ichthyologist Albert Herre was astounded by the fish’s beauty when he described it from the Philippines in 1927. “In life this bizarre little fish is most gorgeously and brilliantly colored,” he wrote. The specific epithet he chose, splendidus, means “glittering” or “brilliant.”

Even the Philippine locals were amazed by this fish, which they had never seen until Herre collected the first (and then only) specimen from a reef in two feet of water. Herre wrote:

“A Samal datu, the headman of the village, when this extraordinary and fantastically marked little creature was placed in his hand, said; ‘I never saw anything like that

before.’ It excited greater interest than I ever saw those keen eyed observers, the Samals, display in a fish.”

However you celebrate the holiday season, we hope it is as “glittering” and “brilliant” as this splendid fish. We will see you in exactly one week for the first “Name of the Week” of 2020!

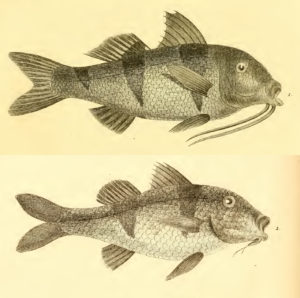

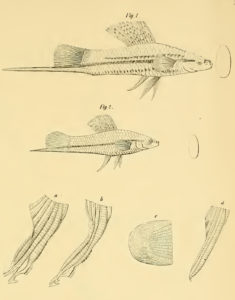

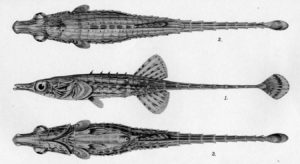

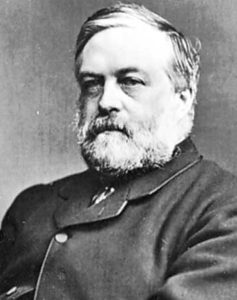

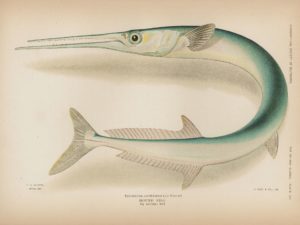

Mullus (now Parupeneus) trifasciatus (top) and Mullus bifasciatus (bottom). From: Lacepède, B. G. E. 1801. Histoire naturelle des poissons. v. 3: i-lxvi + 1-558, Pls. 1-34.

18 December

The 2-banded goatfish with the 3-banded name

A handful of fish names are misnomers, i.e., names that incorrectly describe the fish to which they’re applied. The name of the Indo-West Pacific goatfish Parupeneus trifasciatus appears to be an example. The species was described by French naturalist Bernard Germain de Lacépède (1756-1825) in 1801. The specific name means three-banded (tri-, three; fasciatus, banded). But look at almost any photograph of the fish and it’s clear that it has only two bands. In fact, its common name is Doublebar Goatfish. Did Lacépède make a mistake? Or is there some other explanation?

As he did with several other fishes, Lacépède based his description on an unpublished manuscript and illustration provided by French naturalist Philibert Commerçon (1727-1773). Commerçon sailed the world between 1766 and 1769 under the auspices of the Paris Academy of Sciences, during which he collected and prepared manuscript descriptions of many marine animals and terrestrial plants (including the popular ornamental plant Bougainvillea). Fellow French naturalist Pierre Sonnerat (1748-1814) accompanied Commerçon and illustrated many specimens in the field, including P. trifasciatus. Commerçon died at Mauritius at the age of 45. His extensive collections were brought to Paris after his death. Lacépède was the first to evaluate and systematically organize the fishes Commerçon had collected and provisionally described.

Sonnerat‘s illustration of P. trifasciatus clearly shows a fish with three bands. But Commerçon also provided notes on a similar species with only two bands. Sonnerat provided an illustration for that one as well. Lacépède formally gave it the name bifasciatus (bi-, two; fasciatus, banded).

In 1859, Albert Günther (1830-1914) of the British Museum concluded that P. bifasciatus and P. trifasciatus were the same species. But which name to choose? Günther selected trifasciatus, perhaps because his specimen(s) had two bands and sometimes a third. Günther wrote: “A broad black cross-band over the tail, a second from the anterior portion of the soft dorsal; … sometimes a third black band from the spinous dorsal.”

In 1874, Günther changed his mind and used trifasciatus for the species currently known as Parupeneus multifasciatus (multi-banded) and adopted bifasciatus for the specimen he called trifasciatus in 1859. His illustration shows a fish with three, not two, bands. Arrrggghhhh!

It gets even more confusing. Most fish taxonomists adopted Günther’s 1874 selection of P. bifasciatus over P. trifasciatus. After all, the fish usually has two bands, so bifasciatus makes perfect sense. But in 2002, John E. Randall and Robert F. Myers showed that the bifasciatus name had been used for three different but related goatfishes: P. trifasciatus, P. crassilabrus and P. insularis. They called Günther’s 1874 decision a “mistake.” So they reverted back to Günther’s original 1859 selection of trifasciatus over bifasciatus, citing the “principle of the first reviser.” When there’s a conflict between a choice of nomenclatural acts, the first subsequent author decides which has precedence. In which case, Günther 1859 has precedence over Günther 1874. And so, by rule, trifasciatus becomes the senior synonym of bifasciatus.

One question remain unanswered: Did Commerçon and Sonnerat actually see and accurately render a three-banded goatfish? That’s impossible to say since a type specimen — the actual specimen on which the description was based — was not saved in a museum for future ichthyologists to examine.

The likely explanation is that P. trifasciatus demonstrates some variability in its coloration, possibly dependent on age and/or location. Günther said as much in 1874. In his 2004 revision of the genus, John E. Randall agrees with Günther. Randall said P. trifasciatus has two black to blackish bars, but that a third bar is sometimes present on the caudal peduncle above the lateral line.

Sonnerat’s illustration shows that third band. As did Günther’s from 1874. And if you look deep enough into Google Images, you’ll find a few photographs of Double-Bars Goatfishes (assuming they’re correctly identified) with three bars instead of two.

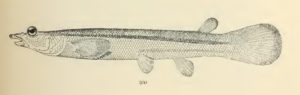

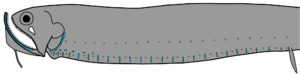

Callionymus aagilis from: Pinault, M., A. Daydé and R. Fricke. 2014. First observation of the slow dragonet Callionymus aagilis Fricke, 1999 in its natural environment. Western Indian Ocean Journal of Marine Science v. 12 (no. 1) (for 2013): 87.

11 December

From A to Z in Eschmeyer’s Catalog of Fishes

The latest (4 December) version of Eschmeyer’s Catalog of Fishes lists 60,249 available species-level names.

The first name, alphabetically listed, is Callionymus aagilis, a dragonet endemic to Reunion and Mauritius and possibly the other Mascarene Islands. The specific name translates as a-, not, and agilis, swift. Although not observed in its natural habitat until 2013, it’s presumed to be a slow-moving species like most of its long-tailed congeners. Small and short-tailed dragonets dash around more quickly.

The last name, alphabetically listed, is also a dragonet, Callionymus zythros from Indonesia and Papua New Guinea. Its specific name is Greek for citrus (e.g., a lemon tree), referring to the yellowish color of the fish’s head and body in alcohol.

Both species were described by Ronald Fricke, C. aagilis in 1999 and C. zythros in 2000. Fricke is also one of the editors of Eschmeyer’s Catalog.

Coincidence?

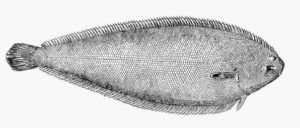

Symphurus civitatum. Courtesy: Wikipedia.

4 December

Symphurus civitatum Ginsburg 1951

Its spelling was changed in 1991. We changed it back this year.

Symphurus civitatum, the Offshore Tonguefish, occurs in the western Atlantic from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, to the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico. It was described by Smithsonian ichthyologist Isaac Ginsburg (1886-1975) in 1951, but he did not explain the meaning of the name. In 1991, Smithsonian flatfish taxonomist Thomas Munroe revised the Western Atlantic tonguefishes of the Symphurus plagusia complex, during which he changed the spelling to “civiatium.”

Munroe wrote: “The etymology of the name civitatum, applied by Ginsburg to this species, is unclear from the original description. The name may have been derived from the genitive plural of civitas (meaning “of the citizenry”). Following this assumption, the proper genitive plural is civitatium, not civitatum as indicated by Ginsburg …”.

Munroe’s revised spelling has been picked up by every major ichthyological reference, including Eschmeyer’s Catalog of Fishes and the American Fisheries Society’s Common and Scientific Names of Fishes from the United States, Canada, and Mexico. Unfortunately, Munroe’s assumption about the meaning of the name is incorrect.

“Civitatum” does not mean “of the citizenry” (which, when applied to this fish, makes absolutely no sense). It actually means “of the states” (e.g., system of states, systema civitatum). It appears that Ginsburg was referring to how S. civitatum occurs along the coast of the United States, whereas S. plagusia occurs in the West Indies and Central America. Although Ginsburg proposed S. civitatum as a full species, he floated the possibility that the S. plagusia complex could be considered three subspecies based on their distribution. On page 199 of the description he wrote:

From one viewpoint plagusia might be regarded as a species that extends from the coast of the United States to South America; that is, including civitatum; and is composed of a number of diverging populations the degrees of divergence of which differ widely. From this viewpoint the populations of plagusia, sensu lato, might be divided into three major groups which might be treated as subspecies, civitatum on the coast of the United States, plagusia, sensu stricto, in the West Indies and Central America, and tesselata on the coast of Brazil and Uruguay.

In other words, “civitatum,” or “of the states,” almost certainly refers to its distribution along the coast of the southeastern United States compared to the distribution (West Indies and Central America) of the closely related S. plagusia.

Furthermore, Ginsburg’s spelling of “civitatum” is a correct genitive plural of civitas.

Want more proof? Ginsburg used the same adjective when he named the eleotrid Erotelis smaragdus civitatum two years later in 1953. Once again, he appears to have used the name to refer to how this subspecies occurs along the northern Gulf coast of the United States whereas the nominate form occurs in the West Indies.

Eschmeyer’s Catalog of Fishes has already corrected the spelling. The next (8th) edition of Common and Scientific Names of Fishes from the United States, Canada, and Mexico should have the original —and correct — spelling as well.

27 November

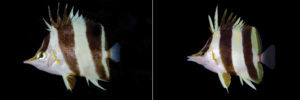

Prognathodes geminus Copus, Pyle, Greene & Randall 2019

Prognathodes geminus (left) and its “twin,” P. basabei (right). From: Copus, J. M., R. L. Pyle, B. D. Greene and J. E. Randall. 2019. Prognathodes geminus, a new species of butterflyfish (Teleostei, Chaetodontidae) from Palau. ZooKeys No. 835: 125-137.

Two weeks ago, ichthyology tragically lost one of its most promising young scientists. Joshua M. Copus, a Ph.D. candidate from the University of Hawaii, died during a deep dive in the Solomon Islands. We do not know the details of the accident.

Josh was a specialist in mesophotic reef-fish communities — fishes that live in coral reefs between 30 and 150 meters deep. He was the lead author on three new-species descriptions:

- Neoniphon pencei Copus, Pyle & Earle 2015, a squirrelfish (Holocentridae), collected at 155 meters off Rarotonga in the Cook Islands.

- Luzonichthys seaver Copus, Ka’apu-Lyons & Pyle 2015, a splitfin (Serranidae) collected between 90-100 meters off the Caroline Islands of Micronesia.

- Prognathodes geminus Copus, Pyle, Greene & Randall 2019, a butterflyfish (Chaetodontidae), collected at 116 meters off Ngemelis Island, Palau. This species, shown here on the left, is named for the Latin word for twin, referring to its similarity in color to P. basabei (at right) from the Hawaiian Islands.

In addition, Josh was the lead author of an important paper on an American freshwater fish far from the mesophotic communities he loved: Geopolitical species revisited: genomic and morphological data indicate that the roundtail chub Gila robusta species complex (Teleostei, Cyprinidae) is a single species. PeerJ 6:e5605: 1-32.

Josh left behind a four-year old son Isaac and his wife Cassie, also a Ph.D. candidate in ichthyology. She is pregnant with their second child.

A GoFundMe memorial fund has been created to support the Copus family during this sad and difficult time.

20 November

20 November

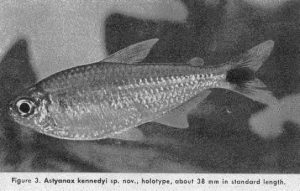

Astyanax kennedyi Géry 1964

This Friday, 22 November, marks the 56th anniversary of the assassination of U.S. president John F. Kennedy. A year after Kennedy’s death, French ichthyologist Jacques Géry (1917-2007) named a new characin in Kennedy’s honor. The description appeared in the December 1964 issue (distributed 18 November) of Tropical Fish Hobbyist magazine.

Astyanax kennedyi occurs in the upper Amazon region surrounding Iquitos, Peru. The type specimens were collected by Jack Roberts, a prominent tropical-fish farmer and dealer at the time. Roberts sent the specimens to Herbert R. Axelrod, the publisher of Tropical Fish Hobbyist. Recognizing that they were new to science, Axelrod sent them to Géry for description.

One can imagine that Kennedy’s death was still fresh in the memories of many people, including those outside America. Géry did not elaborate on what he thought about Kennedy nor why he honored him. He said simply, in a footnote, “In memory of the late President of the United States of America, John F. Kennedy.”

Professor Laszlo Seress’ preparation of a human hippocampus and fornix alongside a seahorse. Courtesy of Wikipedia.

13 November

Hippocampus Rafinesque 1810

Although Rafinesque is credited with establishing Hippocampus, the generic name of the seahorse, he did not coin it. Instead, he borrowed the name of Syngnathus hippocampus proposed by Linnaeus in 1758. Linnaeus likewise borrowed the name. As applied to seahorses, the word “hippocampus” dates to ancient times, although its roots and actual meaning are a matter of some debate.

Most sources tell you that “hippos” means horse and “campus” (from the Greek “kampos”) means monster — in other words, a hippocamp, a mythological creature with the head, torso and forelegs of a horse and the tail end of a fish or dolphin, often depicted as galloping through the oceans of ancient time with Poseidon’s golden chariot in tow. But there are some scholars who say “campus” means caterpillar or silkworm, offering two explanations for this not-so-obvious connection. One explanation points to how the seahorse’s narrow tail is covered in rounded spines, similar to the rows of feet on a caterpillar. Indeed, ancient naturalists, stumped by the bizarre appearance of the seahorse, suggested they were insects that lived in the sea. The other explanation dates to a medieval belief that seahorses were larval dragons.

Whatever the provenance of the name “hippocampus,” one thing is for certain: Every human (and every mammal) has two of them, one on each side of the brain. The hippocampus — named for its seahorse-like shape —plays important roles in the consolidation of information for short-term memory, long-term memory, and the kind of spatial memory that enables navigation. In Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia, the hippocampus is one of the first regions of the brain to suffer damage.

The association of the fish Hippocampus with the brain hippocampus dates to the Italian anatomist and surgeon Giulio Cesare Aranzio (1530-1589) of Bologna (who published under his latinized name, Julius Caesar Arantius). In researching the history of “hippocampus,” we uncovered another, somewhat delightful, connection between fish and brain.

Subsequent anatomists ridiculed Aranzio’s assertion that the hippocampus resembled a seahorse. Based on their dissections, they found nothing seahorse-like in the human brain. “Hippocampus,” as an anatomical term, fell out of use. But in 1896, a Swedish neuroanatomist named Gustav Retzius (1842-1919) proved once and for all that human hippocampus does indeed resemble the fish — if one uses a proper method of anatomical dissection to reveal it. According to a 2010 paper in the journal Translational Neuroscience, that type of dissection consists in stripping off parts of the parahippocampal cortex and subjacent white matter so that the ventral surface of the dentate gyrus becomes freely exposed.

Here’s the part that delights us: Gustav Retzius’ father was Anders Retzius (1796-1861), a prominent anatomist who introduced microscopy in Swedish medical research and published several papers on fish and fish-like animals. It was Anders Retzius’ 1834 paper on the anatomy of the Greater Pipefish Syngnathus acus that was the first to scientifically demonstrated perhaps the most amazing thing about seahorses: It’s the males, not the females, that get pregnant and give birth to live young. (For his contribution to syngnathid biology, the central-west Pacific pipefish Microphis retzii was named in Retzius’ honor.)

Based on the elder Retzius’ association with seahorses, I guess you could say the younger Retzius had “hippocampus” on the brain.

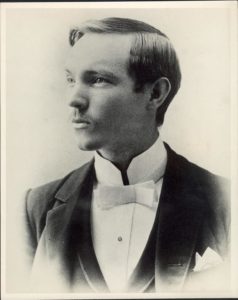

Charles Harvey Bollman (1868-1889)

6 November

Bollmannia Jordan 1890

Two weeks ago, we featured a fictional conversation between David Starr Jordan and his student Charles Harvey Bollman regarding the name and description of the Speckle-tail Flounder, Engyophrys sanctilaurentii. What we did not reveal is that Bollman did not live to see the description published.

Born on Christmas Eve 1868, Charles Harvey Bollman was destined to become one of America’s greatest biologists. He attended Indiana University, studying under Jordan, the dean of American ichthyology, and collaborating with him on two important papers on fishes of the Bahamas and Galapagos Islands. He also authored papers on sunfishes (Centrarchidae), fishes from Michigan, and fishes from the Escambia River of Alabama and Florida. Bollman’s true passion, however, were myriapods (centipedes, millipedes and relatives); he described 65 North American species new to science.

Upon graduating from Indiana University in 1889, Bollman joined the United States Fish Commission. One of his first assignments, if not the first, was to explore the Okefenokee Swamp of southeastern Georgia and northern Florida, the largest freshwater wetland in the United States. Bollman was the only 19th-century ichthyologist to enter the Okefenokee. Tragically, he contracted dysentary while collecting fishes in the swamp and died on 13 July, 1889. He was just 20 years old.

Jordan posthumously named the goby genus Bollmannia in Bollman’s honor, “whose untimely death while engaged in the exploration of the rivers of Georgia, took place while this paper was passing through the press.” Bollman is also honored in the names of a large-tooth flounder (Hippoglossina bollmani Gilbert 1890) and a genus of millipedes (Bollmania Silvestri 1896) from Central and East Asia.

Note that the one letter difference between Bollmannia and Bollmania prevents the latter from being a junior homonym of the former.

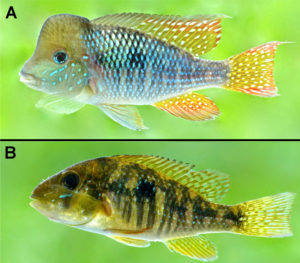

Top: Scorpaena pepo, holotype, male, from: Motomura, H., S. G. Poss and K.-T. Shao. 2007. Scorpaena pepo, a new species of scorpionfish (Scorpaeniformes: Scorpaenidae) from northeastern Taiwan, with a review of S. onaria Jordan and Snyder. Zoological Studies v. 46 (no. 1): 35-45. Bottom: Poropanchax pepo, male coloration in life, from: van der Zee, J. R., K. Bernotas, P. H. N. Bragança, and M. L. J. Stassny. 2019. An unexpected new Poropanchax (Cyprinodontiformes, Procatopodidae) from the Kongo Central Province, Democratic Republic of Congo, American Museum Novitates 3941, 1-12.

30 October

Pumpkinfishes

It’s pumpkin season. Tomorrow is Halloween. Here are two fishes named for the pumpkin cultivar of the winter squash Cucurbita pepo:

The Pumpkin Scorpionfish Scorpaena pepo Motomura, Poss & Shao 2007 occurs on deepwater rocky cliffs off the northeastern coast of Taiwan. It’s named for its bright yellowish-orange body color in life (darker yellow in alcohol).

The description of Poropanchax pepo van der Zee, Bernotas, Bragança & Stiassny 2019 was published just 19 days ago. This member of the African Lampeye family (Procatopodidae) is currently known only from its type locality, 4.5 km northeast of the village of Inga in the Kongo Central Province of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Specimens were collected in a stagnant channel, with sand and boulders, located approximately 180 meters from the main channel of the Congo River. Its discovery is something of a surprise since the closest known congeneric population is located in northwestern Gabon, some 700 kilometers to the north. It too is named for the orange, pumpkin-like color of dorsum and unpaired fins of males.

As for the scientific name of the pumpkin itself, our friends at The ETYPlant Project tell us that “Cucurbita,” derived from a Latin word now applied to the bottle-gourd Lagemaria siceraria, means “gourd-like.” “Pepo” means “sun-cooked” (i.e., ripe and edible), a Latin word for pumpkin.

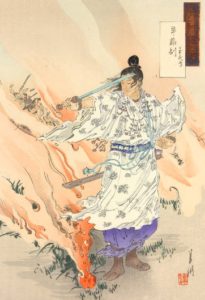

Jacopo Palma the Younger, The Martyrdom of Saint Lawrence, 1581-82.

23 October

Engyophrys sanctilaurentii Jordan & Bollman 1890

This flounder from the eastern Pacific of Baja California south to Peru has an unusual name, in our opinion. The following is an imaginary conversation between the two authors — David Starr Jordan, the dean of American ichthyology, and his student Charles Harvey Bollman — that may explain their thought process in choosing the name they did.

BOLLMAN: Most flatfishes are colored on the eyed side of the body and pale or white on the blind.

JORDAN: Yes, but this one has coloration on the blind side, too. Most peculiar.

BOLLMAN: Five or six curved parallel dusky bands as wide as the eye, the first beginning on the interopercle and curving across the cheeks to along the base of the dorsal; the second beginning at the throat and curving along the posterior margin of the preopercle, and extending on to the back, parallel with the first from the vent; the third curving around in front of pectorals, across the posterior part of opercle, and extending to the base of dorsal fin behind the middle; and the rest of the bands behind the pectorals; all of the bands fading out behind the middle of the body so that the posterior portion is immaculate.

JORDAN: The pattern suggests that of a gridiron, would you say?

BOLLMAN: Indeed it does, Professor! I propose we name it “craticula,” the Latin noun meaning grill, gridiron or griddle.

JORDAN: No, no, no, my young man. Too expected. I suggest we name it “sanctilaurentii” after St. Lawrence, the martyred deacon of Rome.

BOLLMAN: I fail to see the connection, sir.

JORDAN: Then you are as blind as the dextral side of this asymmetrically inclined teleost! St. Lawrence was one of the seven deacons of Rome under Pope Sixtus II. He was burned to death in the 3rd century by Roman Emporer Valerian for defending the Christian faith. Burned on a gridiron, I say. A gridiron!

BOLLMAN: Why, yes, if I recall my Sunday school teachings correctly, the executioners stripped Lawrence, laid him out on the iron grill, piled burning coals under it, and pressed heated iron pitchforks upon his body. And with a cheerful countenance Lawrence said to the Roman official, “Look, wretch, you have me well done on one side, turn me over and eat!”

JORDAN: And that is why St. Lawrence is now considered the patron saint of cooks, chefs and — this part cracks me up — comedians!

BOLLMAN: An excellent name, Professor. Shall we prepare an illustration that shows the gridiron-like markings?

JORDAN: Nah. Future scholars will just have to take our word for it.

Anableps dowii. Drawing by A. H. Baldwin from No. 48214, U.S.N.M., collected by E. W. Nelson in Tehuautepec, México.

16 October

dowei or dowii ?

Recently, the editors at Eschmeyer’s Catalog of Fishes changed the spelling of the specific name of the Pacific Four-eyed Fish from Anableps dowei to Anableps dowii. The editors consulted us on the spelling before they made the change. We investigated the history of the name and presented our findings. We did not recommend one spelling over the other, but we were leaning towards the original spelling of “dowei” based on a very strict interpretation of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature.

Smithsonian zoologist Theodore Gill described the species in 1861. While he did not explicitly state for whom he named the fish, he said the holotype was obtained in El Salvador by Captain J. M. Dow. This would have been John Melmoth Dow (1827-1892), a ship captain for the Panama Railroad Company, shipping agent, and an amateur naturalist. He collected plants and animals that he sent to both American and British museums. A bird (Spangle-cheeked Tanager, Tangara dowii) and at least one orchid (Cattelaya dowiana) are named in his honor.

Several other fishes, all from Central America, are also named after Dow. Albert Günther of the British Museum named seven species after the naturalist, using the spelling “dovii,” in which the “w” is latinized as “v.” Charles Tate Regan described Gambusia dovii (now G. nicaraguensis) in 1913. And Gill described three more species after Dow in 1863: the sea catfish Leptarius (now Sciades) dowii, the mojarra Eucinostomus dowii, and the flyingfish Exocoetus dowii (now a junior synonym of Hirundichthys volador).

Note that Gill spelled the name “dowii” in 1863, instead of “dowei,” as he did in the spelling of the Anableps species of 1861. According to the ICZN Code, a spelling can be corrected if there is proof without recourse to outside sources that the proposed spelling was incorrect due to an inadvertent copyist’s error. But the thing is, Gill used the spelling “dowei” three times in his description. It was the only spelling used. For this reason, the spelling seems intentional, not inadvertent. Although Capt. Dow did not spell his name with an “e,” “dowei” appears to reflect Gill’s intentions. For this reason, the original spelling should be retained.

But when one consults outside sources, there is no doubt that “dowei” is a misspelling. Gill himself changed the spelling to “dowei” (without comment) in a later publication and, of course, used “dowii” for subsequent fishes named for Dow. Even Dow himself used the “dowii” spelling. In a 7 December 1860 article, written before Gill’s description was published, Dow explained how he caught the fish (with a gun!) and the name it was about to receive.

Some time since, while in the Bay of La Union, State of San Salvador, I caught, or rather should say shot with my gun, having no other means at hand, a couple of what I supposed was Anableps tetrophthalmus; but upon sending them to my friend Professor Baird of the Smithsonian Institution at Washington, was somewhat surprised and gratified to hear they were of an entirely new species,—gratified because honoured with having my name given to this singular fish, which has been called A. Dowii” [Dow capitalized the “D”].

Based on this evidence, the ECOF editors decided that “dowei” was an inadvertent error. In those days, copyists manually set type from handwritten manuscripts, so it’s easy to imagine that a copyist misread Gill’s handwriting and consistently (three times) typeset the first “i” of the “ii” patronymic suffix as an “e.” Today, changing one letter in a digital file is an easy thing to do. Back then it was more complicated. Errors—of which there were surprisingly few, given the circumstances—were often corrected in “errata” addenda or tip-in sheets after the fact.

On one hand, I believe “dowei” should be retained because there is no internal evidence that an inadvertent error was made, per ICZN rules. But on the other hand, I believe anyone who has a species named in their honor deserves to have their name spelled correctly.

Pangio bhujia, mature female with eggs. From: Anoop, V. K., R. Britz, C. P. Arjun, N. Dahanukar and R. Raghavan. 2019. Pangio bhujia, a new, peculiar species of miniature subterranean eel loach lacking dorsal and pelvic fins from India (Teleostei: Cobitidae). Zootaxa 4683 (1): 144-150.

9 October

Pangio bhujia Anoop, Britz, Arjun, Dahanukar & Raghavan 2019

We called them the “most unappetizing fishes named for food.” Now the earthworm eel genera Bihunichthys and Chendol — profiled in the 5 June 2019 “Name of the Week” (below) — have a challenger to the claim: a recently described eel loach from India, Pangio bjujia.

One of the authors (Raghavan) saw a photo of the fish posted by a nature enthusiast near the town of Calicut (=Kozhikode) in the southern Indian state of Kerala on social media. He recognized it as something new and unusual. Two other authors (Anoop and Arjun) visited the site and collected specimens for study and description. The fish was captured from a six-meter-deep well used for drinking and irrigation purposes, and from a channel connecting a pond to an adjacent paddy field located ~200 m away from the well. The authors believe it is a subterranean species that lives in the extensive laterite aquifer system of southern Kerala.

Like Bihunichthys and Chendol — named for a noodle and a sweet dessert, respectively — this loach is named for its resemblance to a food, in this case Bikaneri bhujia, a popular (in India) crispy noodle-like snack usually made of moth beans, besan (gram flour) and spices.

A related species, Pangio bitaimac, is named after bee tai mak, a short and thick rice noodle consumed in Southeast Asia.

The genus name Pangio, proposed by Blyth in 1860, is a latinization of Pangya, a local Gangetic name for the related loach P. pangia. It does not, as far as we know, refer to food.

Xiphophorus helleri. From: Heckel, J. J. 1848. Eine neue Gattung von Poecilien mit rochenartigem Anklammerungs-Organe. Sitzungsberichte der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften. Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftliche Classe v. 1 (pt 1-5) [1848]: 289-303, Pls. 8-9.

Xiphophorus Heckel 1848

It’s the cardinal rule when researching the etymology of the name of a fish: Do not rely on secondary sources; instead, always check the original description, even if the meaning of the name is obvious.

Well, we failed to follow that rule in researching the meaning of Xiphophorus, a genus of of viviparous poeciliids popular among aquarists under the common name “swordtails” for the sword-like extension of the lower caudal-fin lobe of males.

Xiphophorus translates as xiphos, sword or saber, and phorus, from phero, to carry or bear. In other words, swordsman. Since the most obvious and famous feature of the type species, X. hellerii, is the sword-like tail, that must be what Heckel was referring to when he coined the name.

But several years ago, we came across a reference — we don’t remember where — that stated that Heckel coined the name not for the tail but for the dagger-like gonopodium (modified anal fin that serves as an intromittent organ) of males. We subsequently saw this claim repeated in dozens of scientific and popular publications and websites. Confident that that was the correct explanation for the name, we chose not to check Heckel’s description. In other words, we got lazy.

A few weeks ago, thinking Xiphophorus might make an interesting “Name of the Week,” we consulted Heckel’s 1848 description for confirmation of the gonopodium claim. Much to our surprise, we found none.

With the help of our good friend Erwin Schraml, we dissected Heckel’s German text and translated the pertinent sections into English. First of all, Heckel never explicitly explained the etymology of the name. And secondly, Heckel used the German equivalents of “sword” and “blade” when describing both the gonopodium and the caudal-fin extension.

- Page 291, anal fin is described as having its anterior rays thickened, “joined together in a long blade”

- Page 291, “anal fin begins in the middle of the body, its sword not longer than the dorsal fin rays”

- Page 292, anal-fin rays form a “strange wide blade”

- Page 294, “Also very conspicuous is the rounded caudal fin, from where from the lower four rays, which are connected to a sharp sword-shaped blade, reach far out. It contains a total of 15 divided rays, two of them belong to that blade.”

- Page 295, “A narrow black ribbon … runs through the caudal fin and forms the upper edge of the pure white sword-shaped appendage up to its tip.”

- Page 295, “the keel of the tail … also adorns a black line, which merges into an intense colored black band, which bounds both sides of the lower edge of the sword-shaped rays of the caudal fin.”

- Page 298, describing anal fin of (now Pseudoxiphophorus) bimaculatus, “These five [rays] are closely attached to one another, covered with a loose skin at the base, and together form the sword …”

- Page 300, referring to (now Poeciliopsis) gracilis, “Anal fin with the whole base placed in front of the dorsal fin, the sword narrow, twice as long as the head …”

- Page 301, the word “sword” appears three more times with respect to the anal fin.

While Heckel used the sword/blade reference eight times for the anal fin (gonopodium) and three times for the caudal-fin extension, we cannot confidently say why he coined the name. He may, as reported elsewhere, have been referring to the dagger-like gonopodium. But he just as easily could have been referring to the much more obvious sword-like tail. Or maybe Heckel was referring to both. Since he didn’t tell us, we cannot know for sure.

We’ve revised the etymology to include all three options: gonopodium, caudal fin, both.

Dicologlossa cuneata. From: Schneider, W. 1990. FAO species identification sheets for fishery purposes. Field guide to the commercial marine resources of the Gulf of Guinea. Prepared and published with the support of the FAO Regional Office for Africa.

26 September

The lawyer-bashing flatfish

Dicologlossa is a genus of soles with just one species, D. cuneata, the Wedge Sole, of the Mediterranean and eastern Atlantic. The specific name “cuneata” means wedge-shaped and refers to its cuneiform shape. The meaning of the generic name is much more interesting.

The name Dicologlossa was proposed in 1927* by Paul Chabanaud (1876-1959), a French ichthyologist who devoted most of his career to the study of the anatomy and systematics of flatfishes. Chabanaud explained that the name derives from dicholo[gos], meaning advocate or lawyer, and glossa, tongue. He also explained that the name was was inspired by its local name in Arachon, France “langue d’avocat,” or lawyer’s tongue.

“Lawyer’s tongue” is a more colorful way of saying “pointed tongue,” in this case probably referring to the sole’s body shape. The name could also refer to the pointed leaves of the succulent genus Gasteria, known in English as “Lawyer’s Tongue.”

We don’t know the provenance of the phrase “Lawyer’s Tongue,” but considering that Gasteria succulents are also called “Mother-in-law’s Tongue,” we’re guessing the comparison is not complimentary.

Smooth and slippery, perhaps? 🙂

* Chabanaud changed the spelling to Dicologoglossa in 1930 but his original spelling stands.

Nothobranchius furzeri from NFIN, The Nothobranchius furzeri Information Network

18 September

Nothobranchius furzeri Jubb 1971

This biographical footnote has nothing to do with the fish nor why it was named “furzeri.” But it’s interesting nonetheless.

Richard E. Furzer was an American aquarist and bird breeder who lived for 25 years in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). He discovered this annual killifish in 1968 and distributed it to killifish hobbyists upon his return to the U.S. shortly thereafter. Reginald A. “Rex” Jubb (1905-1987), of the Albany Museum in Grahamstown, South Africa, described it in the Journal of the American Killifish Association. He named it in honor of Furzer, “through whose efforts this beautiful fish was introduced to Nothobranchius enthusiasts.”

Now here’s the interesting part, which, as I said, has nothing to do with the fish.

Furzer not only brought African fishes to America, he brought birds as well. In 1993, he pleaded guilty to five felony counts when accused of using false documentation to illegally ship into the U.S. nearly 2,400 African Grey Parrots, a CITES Appendix II species, between 1988 and 1990, worth up to $1,000 each. He was sentenced to 18 months in jail and ordered to pay a $75,000 fine.

In 1997, the PBS science TV series “Nova” broadcast an episode about the U.S. government sting operation that brought down Furzer and other bird smugglers. Furzer said on the program:

“I was aware that the birds did not come from the Ivory Coast or Guinea, and to my mind, it didn’t make any difference. They don’t have border laws in west Africa like we do here, and they don’t care where the birds came from, and I really didn’t think that it was a crime. I realized that I was lying to the government, telling them the birds came from one country instead of another, but morally, it was fine by me.”

Back to the fish itself: Nothobranchius furzeri is said to have the shortest known lifespan for a vertebrate, with a life expectancy in the wild of 6-9 months (due to desiccation of its habitat) and a maximum life span in the aquarium of less than 12 weeks (where they undergo the same functional deteriorations associated with typical vertebrate aging). As a result, N. furzeri is widely used as a laboratory model species in aging research.

11 September

Pseudobatos buthi Rutledge 2019

Welcome to the world P. buthi! I discovered a new species of ray called a guitarfish from the Gulf of California. (Also includes morphological analysis of all eastern pacific guitarfishes and dichotomous key) Read here. #newspecies https://t.co/YmspnwgiKF pic.twitter.com/tosvnqwBfE

— Dr. Kelsi Rutledge (@fishandfreckles) August 30, 2019

The last two “Name of the Weeks” have been about deaths. This week we commemorate a birth. Not an actual birth. But a clever awareness-raising tactic about a new-species description in the form of a mock birth announcement.

In the 1940s and 1950s, ichthyologist Boyd Walker (University of California, Los Angeles) and colleagues caught 80 individuals of guitarfish during various collecting trips in the Gulf of California. Walker recognized these specimens as a possible new species but never examined them for quantifiable differences. Last year, UCLA Ph.D. student Kelsi M. Rutledge quantified those differences and described a new species, Pseudobatos buthi, which she named in honor of her mentor and M.Sc./Ph.D. advisor, Donald Buth. The description of P. buthi appear in the September issue of Copeia.

As the online version of Copeia became available, Rutledge decided to have some fun. She grabbed one of the museum specimens (preserved, not alive!) of her new species, went to the beach, and posed for several photographs of her and her new “baby.” She posted the photos on Twitter, writing “Welcome to the world P. buthi! I discovered a new species of ray called a guitarfish from the Gulf of California.”

Reaction has been positive. “This could be the start of a brilliant new trend in scientific publication announcements,” wrote physicist David Mills.

“We’re starting to see more and more people taking creative approaches to getting the word out there,” David Shiffman told Smithsonian.com. He’s a marine conservation biologist and elasmobranch specialist who runs the Twitter account Why Sharks Matter. “Her photoshoot was one of the most hilarious things I’ve ever seen in that space.” Rutledge says her “silly” birth announcement has a serious objective. About 55 percent of guitarfishes are either threatened or near threatened for extinction. “I am trying to raise awareness about this understudied group of fishes,” she says. She also wanted to draw more attention to taxonomy.

“Other scientists see [taxonomy] as boring or low impact, but I wanted to highlight that taxonomy can be fun, and it is important.”

4 September

Rudolf H. Wildekamp (1945-2019) and Phillip C. Heemstra (1941-2019)

Within a few days of posting last week’s entry on overlooked deaths from 2018 and early 2019, news of two recent deaths reached our email inbox: Dutch killifish aquarist and ichthyologist Rudolf H. Wildekamp and South African ichthyologist Phillip C. Heemstra.

Born in a church after evacuating their home due to the WW2 Battle of Arnhem, Rudolf H. Wildekamp (1945-2019) — or Ruud, as he was called — was destined to love animals. His father, after all, was a supervisor of the zoo in Rhenen. Ruud apparently spent a lot of time there. His foot was mangled somewhat when a lion tried to pull a young Ruud through the bars. When he entered the military, his love of animals was put to work. One of his jobs was to chase the birds near the runways of two military air bases. Ruud apparently became interested in African annual killifishes while working on an anti-malaria project in Africa. Seeing as how these fishes ate mosquito larvae, he began keeping and breeding them in aquaria.

Eventually, Ruud became a worldwide expert on African killifishes. He collected them, bred them, photographed them, illustrated them, and discovered and described dozens of new species, particularly those of the genus Nothobranchius. His works appeared in a wide variety of hobbyist and professional publications. From 1992 to 2004, he published four volumes of “A world of killies. Atlas of the oviparous cyprinodontiform fishes of the World” through the American Killifish Association. Both written and illustrated by Ruud, this ambitious project aimed to survey distributional, taxonomic, biological and aquaristic data for all killifish species, not just those from Africa. The series was never completed; we don’t know why. (But we’re told a new book by Ruud is coming out later this month.)

Eventually, Ruud became a worldwide expert on African killifishes. He collected them, bred them, photographed them, illustrated them, and discovered and described dozens of new species, particularly those of the genus Nothobranchius. His works appeared in a wide variety of hobbyist and professional publications. From 1992 to 2004, he published four volumes of “A world of killies. Atlas of the oviparous cyprinodontiform fishes of the World” through the American Killifish Association. Both written and illustrated by Ruud, this ambitious project aimed to survey distributional, taxonomic, biological and aquaristic data for all killifish species, not just those from Africa. The series was never completed; we don’t know why. (But we’re told a new book by Ruud is coming out later this month.)

Two African killifishes have been named in Ruud’s honor. In 1973, Berkenkamp described Aphyosemion wildekampi from Cameroon; Ruud had bred the species and sent specimens to Berkenkamp for the description. In 2009, Costa described Nothobranchius ruudwildekampi from Tanzania; he cited Ruud’s “fine taxonomic work” on the genus.

Rudolf H. Wildekamp passed away on 18 August.

Eleven days later, on 29 August, another ichthyologist associated with Africa passed away — Phillip C. Heemstra.

Born in Illinois, USA, in 1941, Heemstra earned his doctorate in marine biology at the University of Miami (Florida, USA) in 1973. He worked in Australia from 1974 to 1977. Then, in 1978, he made the move that would define his career, relocating permanently to South Africa as curator of fishes of the famous J. L. B. Smith Institute of Ichthyology (now the South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity). There Heemstra distinguished himself contributing to the taxonomy of a wide range of fishes, including rays, groupers, marine angelfishes, and pufferfishes. Much of Heemstra’s work was published in book form, including “Fishes of the Southern Ocean” (with Ofer Gon, 1990), “Groupers of the World” (with John E. Randall, 1993), “Coastal Fishes of Southern Africa” (with his wife Elaine Heemstra, 2004), and an undisputed classic of ichthyological literature, “Smith’s Sea Fishes” (with Maragaret Smith, 1986).

Born in Illinois, USA, in 1941, Heemstra earned his doctorate in marine biology at the University of Miami (Florida, USA) in 1973. He worked in Australia from 1974 to 1977. Then, in 1978, he made the move that would define his career, relocating permanently to South Africa as curator of fishes of the famous J. L. B. Smith Institute of Ichthyology (now the South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity). There Heemstra distinguished himself contributing to the taxonomy of a wide range of fishes, including rays, groupers, marine angelfishes, and pufferfishes. Much of Heemstra’s work was published in book form, including “Fishes of the Southern Ocean” (with Ofer Gon, 1990), “Groupers of the World” (with John E. Randall, 1993), “Coastal Fishes of Southern Africa” (with his wife Elaine Heemstra, 2004), and an undisputed classic of ichthyological literature, “Smith’s Sea Fishes” (with Maragaret Smith, 1986).

Nine fishes have been named after Heemstra. The first is a species of skate, Okamejei heemstrai (McEachran & Fechhelm 1982), from the western Indian Ocean; Heemstra furnished specimens of the new species and was “extremely cooperative” in supplying the authors with elasmobranch material from South Africa. The most recent is a species of lanternbelly, Acropoma heemstrai Okamoto & Golani 2017, from off the coast of Dokodweni, South Africa. Heemstra was honored for his “great contributions to percoid studies in the western Indian Ocean.”

Heemstra’s wife Elaine, is Senior Artist at the ichthyology Institute. She illustrated many of her husband’s works. They are honored together in the name of the snake eel Luthulenchelys heemstraorum McCosker 2007, specifically for their “efforts to understand, illustrate, and explain the fishes of the Indian Ocean to scientists and the general public.”

The Heemstra’s final project together, the six-volume “Coastal Fishes of the Western Indian Ocean,” 20 years in the making, is scheduled for publication in 2020. View a sneak preview here.

28 August

In Memoriam: 5 belated obituaries

We have overlooked the deaths of several notable figures in ichthyology, fisheries science and oceanography who passed away during the past 18 months. Here we briefly review their lives, contributions, and the fishes for which they’re named.

Eric Godwin Silas (1928-2018) was a Sri Lankan-born ichthyologist and fisheries scientist. He worked for the Zoological Survey of India (1949-1955), at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla, California (1955-1956), and served as Director of the Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute in Cochin, India. He is honored in the names of three fishes from India: a swellshark Cephaloscyllium silasi (Talwar 1974), a hillstream loach Ghatsa silasi (Madhusoodana Kurup & Radhakrishnan 2011), and a shark catfish Pangasius silasi Dwivedi, Gupta, Singh, Mohindra, Chandra, Easawarn, Jena & Lal 2017. All three descriptions cite his outstanding contributions to the taxonomy of Indian fishes.

Also from India is ichthyologist Naresh Chandra Datta (1934-2018). Revered as the “Professor of Professors,” he spent his entire career at the University of Calcutta, where founded its Fishery and Ecology Research Unit and served as head of the Department of Zoology. The hillstream catfish Erethistes nareshi (Mahapatra & Kar 2015) is named in his honor.

Volker Mahnert (1943-2018) was an ichthyologist, arachnologist, parasitologist, and director of the Natural History Museum of Geneva. He published around 200 papers on a variety of animals, most notably pseudoscorpions, wherein he named 351 new taxa. His work on fishes focused on the order Characiformes, including the description of the Rummy-nose Tetra Hemigrammus bleheri, an aquarium favorite. Two fishes are named in his honor: the tetra Hemigrammus mahnerti Uj & Géry 1989 and the stone loach Schistura mahnerti Kottelat 1990.

Oscar León Mata (1964-2018) was a killifish collector and aquarist, environmental engineer, and fish curator (Museo de Ciencias Naturales in Guanare) who dedicated much of his too-short life to Venezuelan ichthyology. For his assistance in the field he is honored in the names of three fishes: the annual killifishes Renova oscari Thomerson & Taphorn 1995 and Austrofundulus leoni Hrbek, Taphorn & Thomerson 2005, and the bristlenose catfish Ancistrus leoni de Souza, Taphorn & Armbruster 2019. According to ichthyologist Donald Taphorn (pers. comm.), “Oscar died of bone cancer because of the disi tegration of the Venezuelan state caused by Chavez and the Cuban communist regime. He unfortunately died without ever getting treatment. We organized a fund to help, but there was no medicine available in Venezuela for his treatment, and no gasoline in Guanare when he became deathly ill to allow travel to Colombia, where we had arranged to purchase the medicine. So he is a victim of the political chaos that continues in Venezuela to this day.”

Walter H. Munk (1917-2019) was a professor of geophysics at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla, California. During World War II, Munk and his doctoral advisor developed methods for predicting surf conditions on beaches, saving countless lives during allied landings in North Africa, the Pacific and Northern Europe. He studied a wide range of oceanographic subjects, including surface waves, geophysical implications of variations in the Earth’s rotation, tides, internal waves, deep-ocean drilling into the sea floor, acoustical measurements of ocean properties, sea level rise, and climate change. The Pygmy Devil Ray Mobula munkiana was named for Munk by his student Giuseppe Notarbartolo di Sciara in 1987. Munk passed away from pneumonia in February, aged 101.

PHOTO: Holotype of Mobula munkiana. From: Notarbartolo-di-Sciara, G. 1987. A revisionary study of the genus Mobula Rafinesque, 1810 (Chondrichthyes: Mobulidae) with the description of a new species. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 91 (1): 1-91.

21 August

21 August

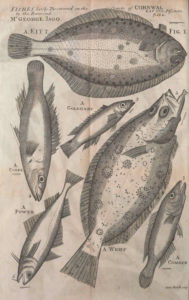

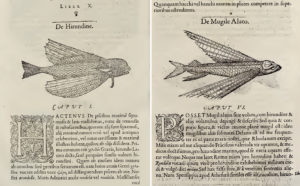

Lepidorhombus whiffiagonis (Walbaum 1792)

Lepidorhombus whiffiagonis is a turbot (family Scophthalmidae) that occurs in Western Baltic Sea, North Sea, Mediterranean Sea, and in the eastern Atlantic from Iceland and Norway south to western Sahara. Its name dates to George Jago, a parish priest in the village of Looe in Cornwall, England. In his spare time he researched and illustrated Cornish fishes for a book on the subject. But Jago died in 1726 before completing the work and his notes were lost. However, Jago shared some of his illustrations with fellow parson-naturalist John Ray (1627-1705), who included them in his Synopsis Methodica Piscium (shown here), published posthumously in 1713. The illustrations, as published by Ray, also include the local Cornish names Jago had recorded for each fish: Kitt. Goldsinny. Cooke. Power. Comber. Whiff.

Decades later, German physician-naturalist-taxonomist Johann Julius Walbaum (1724-1799) kept himself busy by renaming fishes described by early naturalists, including John Ray, using the still-new system of bionomial nomenclature created by Linnaeus. One of these was the Whiff, a turbot or flatfish, one of Jago’s fishes from Cornwall. Walbaum called it Pleuronectes Whiff-Iagonis. “Pleuronectes” is an early catch-all genus for flatfishes (pleuro = side, nectes = swimmer), i.e., a fish that swims on its side, which all adult flatfishes do.

“Whiff-Iagonis,” now spelled whiffiagonis, delightfully honors both the man who introduced this species to science and the name he recorded for it. “Iago” is a latinization of Jago.

So the name means, literally, Jago’s Whiff.

Footnote: Why is a Cornish flatfish called a Whiff? We don’t know for sure. According to Houghton’s Natural History of Commercial Sea Fishes of Great Britain and Ireland (1884), the name may refer to the fish’s habit of becoming lively before a storm, when the winds blow or whiffle about.

Garra smarti at type locality. Photo by K. Kawai. From: Krupp, F. and K. Budd. 2009. A new species of the genus Garra (Teleostei: Cyprinidae) from Oman. aqua, International Journal of Ichthyology v. 15 (no. 2): 117-120.

14 August

Around the world with Garra smarti

UPDATE 8 March 2023 Per Sayyadzadeh et al. (2023), G. smarti is now considered a junior synonym of G. dunsirei. Garra smarti is a cyprinid fish known only from Wadi Hasik in the Dhofar Province of Oman. It was described by Krupp and Budd in 2009 based on 11 specimens, 24.8 to 49.5 mm standard length. They named the fish for Emma Smart (b.1978), a British biologist who at the time served as a Conservation Officer for the Emirates Wildlife Society in Dubai. The authors credited her studies of Arabian wadi (=valley) fish and her contributions to the conservation of freshwater habitats throughout the Arabian Peninsula. She also collected type specimens and provided detailed information about type locality.

Smart discovered the fish in August 2002, when a flash flood occurred in Wadi Hasik, resulting in a complete temporary transformation of the topography of the wadi. The flood waters extended to the Arabian Sea, connecting isolated pools into a flowing, turbid “river” that filled the surface area of the wadi bed for several kilometers. Smart discovered the fish swimming in shoals near the surface of a large pool under a waterfall.

Exploring remote areas appears to be Smart’s passion in life. Ten years after discovering this fish, she her partner (now husband) embarked on a big adventure — circumnavigating the world in a 1994 Toyota 4×4 in 800 days! While they missed the 800-day mark (many setbacks, personal, financial and mechanical), what they’ve done is still incredible, driving through 51 countries so far. They’re currently in the UK fixing and modifying their 4×4. A trip through the Americas is being planned for later this year.

You can track their progress, read their blog, see photos, and watch videos at their superb website.

We could not find a portrait of Noël de la Morinière. So here is one of Charles-Alexandre Lesueur from 1818, painted by Charles Willson Peale. Note the eel in the jar.

7 August

Ameiurus natalis revisited

For our 24 June 2014 Name of the Week, we discussed the specific name of the North American catfish Ameiurus natalis (Lesueur 1819), known as the Yellow Bullhead. We disputed the long-held assumption that “natalis” means “having large buttocks,” referring to either a swollen and elevated caudal peduncle, a large adipose fin, or the swollen head and nape muscles of breeding males. Instead, we argued that “natalis” means “of or belonging to birth,” a word often applied to the Christian holiday of Christmas. Our evidence for this was that Lesueur called the catfish “Pimelode Noël,” Noel being French for Christmas. What we could not explain was why Lesueur named this catfish after Christmas. Was it the red and greenish (olive) tint on the body? Did he collect it on Christmas Day? We didn’t know.

A few weeks ago, while researching the names of carangiform fishes, we came across Scomberoides noelii, proposed by Lacepède in 1801. While the species is now considered a nomen dubium or species inquirenda, we immediately sensed that we had found the Noël (and natalis) of “Pimelode Noël.” Indeed, we had. Lacepède said he named the fish in honor of Simon Barthélemy Joseph Noël de la Morinière (1765-1822) of Rouen, France, as a “solemn mark of gratitude and esteem” to a man “who very much deserves the everyday thanks of naturalists for his labors, and whose precise observations have enriched so many pages of the [natural] history that we write” (translation).

Little known today, Noël was well-known in his lifetime. He studied law but also became an expert in fish culture. He published a natural history of herring in 1789 and edited the Journal de Rouen, a newspaper, from 1792 until 1799. Between 1795 and 1802 he authored works on the geography, river navigation, and fisheries of the Seine-Inférieure department in Normandy, as well as treatises on the natural history of smelt and the history of whaling. He served as a commissioner of the Seine-Inférieure (1800-1806), eventually becoming inspector general of French fisheries, a position he held until his death. He devoted 20 years to a projected six-volume history of fisheries, but only one volume was completed (1815). In 1813, Noël wrote a letter to American president Thomas Jefferson, also a naturalist, seeking information on American fisheries for his book.

Lesueur and Noël knew each other in France. What’s more, Lesueur mentioned Noël in his 1817 description of the American Eel, Anguilla rostrata. “Natalis” is simply a latinization of “Noël.” Perhaps Lesueur was being coy in not explicitly calling out Noël’s name. Or perhaps Noël was so famous in France (the description appeared in a French journal) that everyone understood the “natalis” reference.

A detailed etymological and historical analysis of Ameiurus natalis is available here.

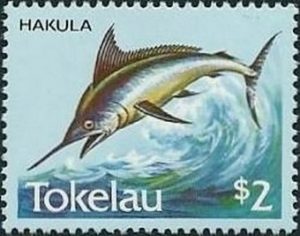

Black Marlin, Istiompax indica, as shown on a stamp from New Zealand.

31 July

Istiompax Whitley 1931

Australian ichthyologist Gilbert Percy Whitley (1903-1975) was fond of coining enigmatic names (see Aidablennius, 2 January, below). His name for the monotypic Istiompax is a riddle wrapped inside a mystery. Literally.

The Black Marlin, Istiompax indica, is a recreationally important billfish that occurs in tropical and subtropical areas of the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is one of the fastest fishes in the world, having been recorded at 105 km/h. Whitley proposed the generic name in 1931 for what he believed was a new species, Istiompax australis (which has since been synonymized with Tetrapturus indicus Cuvier 1832).

The “Istio-” part of the name clearly refers to istius, meaning sail, the root word of Istiophorus (bearing a sail, referring to the sail-like dorsal fin), the type genus of the family Istiophoridae. The “ompax” part of the name is the mystery. The word does not occur in any Greek or Latin dictionary that we know of. But it does occur in the name of a legendary Australian hoax fish Ompax spatuloides. Long story short: In 1879, Francis de Castelnau described a bizarre freshwater fish from Australia based on a drawing reputed to be real was actually assembled from the parts of other creatures, including the tail of an eel and the bill of a platypus. It was a hoax, but Castelnau, eager to put his name to such a remarkable creature, was easily duped. Since the fish was shrouded in mystery, Castelnau gave it the name Ompax, which he described as a “mysterious historical” name. The true meaning of the name itself is shrouded in mystery, but it appears associated with the religious rites of Demeter, a Greek goddess of the harvest and agriculture.

So how does this connect to the name of the Black Marlin? We can only speculate. Two things are worth noting. When he proposed Istiompax, Whitley said that I. australis had been misidentified by Australasian authors as either one of two species, Tetrapturus indicus or Makaira mazara. Knowing this, one could say there was some mystery concerning this marlin’s true identity. The same could be said for Ompax. In fact, it was Whitley himself who helped expose the Ompax hoax in an article he published less than two years later in 1933.

With Ompax on his mind, was Whitley drawing a parallel between two mysterious and misunderstood fishes?

We shared this explanation with two well-known ichthyologists to see if it had any merit. They both agreed it did. One of them said, “Your explanation is right along Whitley’s lines, who had a very special sense of humor.”

24 July

Revising, revising, always revising

Once an etymological explanation is posted to ETYFish.org, it isn’t necessarily “done.” We’re always revising, correcting and tinkering with our explanations based on new research, new information, user comments, or simply seeing enigmatic names in a new or fresh light. With 30,644 fish-name etymologies posted as of today, it’s a time-consuming — and never-ending — task, but one we feel is essential to making The ETYFish Project a useful and trusted resource. Here are three revisions among the hundreds we’ve made over the past four months:

Neobythites unicolor Nielsen & Retzer 1994 Fishes described from dead specimens in jars of formalin often have different colors or color patterns than their living brethren. This species of cuskeel was described from museum specimens that had been preserved for nine years after being collected in the Caribbean, the Gulf of Mexico, and adjacent areas of the tropical northwestern Atlantic. The specific epithet “unicolor,” i.e., one-colored, refers to the uniformly yellowish coloration and lack of color markings of these preserved specimens.

In-situ observations from a manned submersible, however, reveal that living N. unicolor are actually spotted! As reported in a recent issue of Copeia, living and fresh specimens seen at 269–609 m show a large number of distinctive, dark, rounded or irregularly shaped spots distributed on head, dorsal portion of body, and dorsal fin. This color pattern fades when fish are frozen, and it is completely lost during preservation over several years. We have added this information to the entry.

Farlowella smithi Fowler 1913 This catfish from the Amazon River basin of Brazil, Bolivia and Colombia was named in honor of Edgar A. Smith, who collected the type. When we first posted the entry, we could not find any additional information about Smith and had no idea who he was. Now we’re sharing data with the authors of the upcoming Eponym Dictionary of Fishes, the same folks who brought you the Eponym Dictionary of Birds and follow-up volumes on mammals, reptiles, amphibians, sharks, and damselflies and dragonflies. Thanks to them, we know now that Edgar A. Smith was a member of the Madeira-Mamoré expedition (1907-1912) commissioned by the Brazilian Government to build a railway along the banks of the Rio Madeira, during which he collected the holotype. He died in 1953.

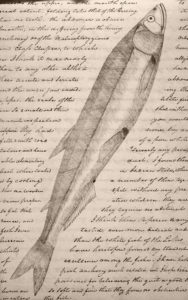

In February 1806, 31 years before it received its scientific name, explorer Meriwether Lewis drew Thaleichthys pacificus in his sketchbook. Lewis first encountered the fish when Clatsop Indian chief Coboway offered some for sale at Fort Clatsop (named for the tribe), near the mouth of the Columbia River in Oregon, USA.

Sometimes our attempts to bring clarity to enigmatic names does just the opposite. As in this case of Thaleichthys Girard 1858. This is the generic name for the Eulachon, T. pacificus, an anadromous fish found from northern California to southwest Alaska. It was an important subsistence food for native Americans during harsh winters, and with its oily flesh it could be dried and used as a candle (hence the alternate common name Candlefish). Since Girard did not provide an explanation for the first part of the name (ichthys, of course, means fish), we surmised that “thale” was derived from “thalia,” meaning either “rich” (referring to its oily flesh) or “abundant” (referring to Richardson’s 1837 description of T. pacificus, in which he described “immense shoals” of this fish during its freshwater spawning run).

Upon taking another look at Girard’s description of the genus, however, we noticed that he did not mention its oily flesh nor its abundance. In fact, Girard established the genus for what he believed was a new species, Thaleichthys stevensi, based on a single specimen from Puget Sound (Washington, USA). Girard described this species (now considered a junior synonym of T. pacificus) as if he were completely unaware of the common and artisanally important Eulachon. If that is the case, then there is no internal evidence that the “thale” in Thaleichthys means rich or abundant. So we have amended the entry to reflect this ambiguity and added a third, equally speculative explanation: “thale” means “vigorous,” referring to their fast-swimming schooling behavior (again, not mentioned by Girard, but it fits the fish nicely).

You can follow our revisions, as of 6 April 2019, here.

Pristolepis grootii from Bleeker, P. 1876-77. Atlas ichthyologique des Indes Orientales Néêrlandaises, publié sous les auspices du Gouvernement colonial néêrlandais. Tome VIII. Percoïdes II, (Spariformes), Bogodoïdes, Cirrhitéoïdes. Fréderic Muller & Co, Amsterdam. v. 8: 1-156, Pls. 321-354, 361-362.

17 July

“I am Groot.”

The recent description of a Cirrhilabrus wakanda, an East African fairy wrasse named for the fictional country of Wakanda from Marvel Comics’ Black Panther, is currently popping up on blogs and Facebook pages everywhere. So we won’t repeat the news here. And we won’t repeat the phrase everyone who’s writing about this fish is duty bound to say: “Cirrhilabrus wakanda forever!” (There, we just did.)

Instead, for all you MCU fans out there, we’ll highlight a fish name no one is talking about.

The fish named after Groot.

In 1852, Pieter Bleeker described Pristolepis grootii, a Malayan leaffish (Anabantiformes: Pristolepididae) from the Tjirutjup River of Blitong, Indonesia. As you’ve probably guessed, it is not named for the lovable tree-like being from Guardians of the Galaxy who can mutter only three words: “I am Groot.” Instead, it’s named in honor of Cornelis de Groot van Embden (1817-1896), a Dutch naturalist and ethnographer to whom, Bleeker wrote, “science owes the first knowledge of the freshwater fauna” (translation) of the Indonesian location where it was found. In 1887, Groot published Herinneringen Aan Blitong, in which he described the natural history, geology and people of Blitong Island. The book is still available today.

Pristolepis grootii is the only fish in the world that can legitimately claim, “I am Groot.”

10 July

10 July

Astyanax leonidas Azpelicueta, Casciotta & Almirón 2002

How do we commemorate the 300th consecutive “Name of the Week” since the series began on 17 October 2013? With a name that commemorates the 300-man army that took on 70,000- 300,000 Persian soldiers at the Battle of Thermopylae in 480 BC.

Astyanax leonidas is a tetra (family Characidae, subfamily Stethaprioninae) from the Paraná River basin of Argentina. Its specific name refers to the Spartan King Leonidas, who led the 300-man army into battle and died doing so. A fictional (and fantastical) retelling of story was featured in the 1998 comic book series and 2006 film “300.”

The authors chose the name “leonidas” as a dedication to “all the academic teachers of Argentina that stand in defense of a free and independent education.”

The meaning of the generic name Astyanax is uncertain. Baird & Girard did not explain the significance of the name when they proposed it in 1854. In Greek mythology, Astyanax — which means “protector of the city” — is the son of Hector, a Trojan warrior. Our best guess is the name refers to the large silvery scales of the type species A. argentatus, which could be said to resemble armor.

Betta persephone (male) by Martin Fischer. Courtesy: Wikipedia.

3 July

Betta persephone Schaller 1986

Here’s a case in which a piece of misinformation about a fish’s name is presented on one website and then repeated on multiple websites until it becomes an established, footnoted “fact.”

Betta persephone is a species of fighting fish — a cousin to those sold by the millions in tiny glass bowls and plastic cups all over the world — known only from a very small area of primary peat forest in Malaysia. Due to urbanization and forest clearing for oil palm cultivation, the species is near extinction in the wild. Fortunately, Betta specialists are keeping it alive in captivity.

According to the aquarium website SerouslyFish.com, Betta persephone is named for the Greek goddess Persephone, daughter of Demeter and Zeus and queen of the Underworld, in allusion to the largely blackish color pattern of males (females tend to be brownish). This explanation has been picked up by several websites, including Wikipedia. Unfortunately, it’s only half right.

Knowing a bit more about Persephone helps us understand the fish’s name. Persephone became queen of the Underworld when she was kidnapped by Hades, who she subsequently married. But Hades allowed Persephone to visit her mother in the world above — the upper world. It’s this living in two worlds — upper and lower — that explains the Persephone allusion.

Tropical-fish importer Dietrich Schaller clearly explained the name when he described the species in the German aquarium magazine Die Aquarien- und Terrarienzeitschrift (DATZ). According to Schaller, the name refers to how the fish adapts to environmental conditions. When water is available, it lives as any fish would, swimming above the leaf-litter substrate of peat-forest swamps and streams. When conditions are dry, however, the fish buries itself within the moist leaf litter in order to stay alive.

The name has nothing to do with the blackish color of males. And that’s a fact we hope that future websites will footnote. To here.

26 June

Robert F. Inger (1920-2019)

Anyone who studies the freshwater fishes of Borneo will have a well-thumbed monograph in their bookshelf, or one frequently opened PDF on the computer desktop: The freshwater-fishes of North Borneo (1962) by Robert F. Inger and Chin Phui-Kong. Last week we learned that Dr. Inger passed away in April at the age of 98. (Dr. Chin passed away in 2016.)

Robert (“Bob”) Frederick Inger was born in St. Louis, Missouri, USA. He received his Bachelor of Science degree in 1942 at the University of Chicago. After serving in World War II as a map maker working for Gen. Patton in France and Germany, he returned to the University of Chicago to complete his Ph.D. His career-long association with Chicago’s Field Museum of Natural History began as a volunteer when he was an undergraduate. After completing his doctorate, he was hired at the Field Museum where he shortly become the Assistant Curator of Fishes and then Curator of Amphibians and Reptiles. After serving as Assistant Director from 1971-1978, he returned to the Division of Amphibians and Reptiles as Curator from 1979 until retirement in 1995. As Curator Emeritus, he continued his research on the systematics and ecology of reptiles and amphibians of Southeast Asia and associated field studies in some parts of Asia with emphasis on Sabah and Sarawak, Malaysian states in the Island of Borneo.

Dr. Inger was honored with the title “Datuk” by the Government of Malaysia in the state of Sarawak where he conducted reptile and amphibian monitoring from 1950 to 2007.

For decades after retirement, he was in his museum lab almost every weekday. Over the course of his long career, Datuk Dr. Inger authored 11 books and over 130 peer-reviewed papers. He described or co-described over 75 species new to science, including 25 fishes, and over 40 new species have been named after him by other scientists, including three fishes, all endemic to Sabah, Borneo:

-

- Stenogobius ingeri Watson 1991, a goby (Inger collected the holotype in 1956)

- Osteochilus ingeri Karnasuta 1993, a cyprinid (Inger collected the holotype during the same expedition in which he collected the goby)

- Gastromyzon ingeri Tan 2006, a sucker (Inger was honored for his contributions to the ichthyology and herpetology of Borneo)

In addition, both Inger and his Malaysian collaborator Chin Phui-Kong were honored in the name of the East Asian minnow Parachela ingerkongi, described by Bănărescu in 1969.

Indostomus paradoxus, type specimen. From: Prashad, B. and D. D. Mukerji. 1929. The fish of the Indawgyi Lake and the streams of the Myitkyina District (Upper Burma). Records of the Indian Museum (Calcutta) v. 31 (pt 3): 161-223, Pls. 7-10.

19 June

The evolutionary and etymological enigma of Indostomus paradoxus

This is the fish that inspired my interest in fish systematics.

It was in the late 1970s. I was in my teens, spending what few dollars I had left over after buying tropical fishes and supplies on aquarium books, including the looseleaf edition of Exotic Tropical Fishes. Inserts, each one featuring a different fish species, were published every month in Tropical Fish Hobbyist magazine. You could also buy packets of previously published inserts at better aquarium stores. (For me, that was That Fish Place, still in business today, in Lancaster, Pennsylvania.)

Insert #143 was particularly fascinating. It was for the Paradox Fish, Indostomus paradoxus, of Lake Indawgyi of Burma (now called Myanmar). Decades after receiving this insert and inserting it into the looseleaf binder, I still remember the opening sentences:

Nearly every aquarium fish has species to which it is closely related. Not so with Indostomus paradoxus. It does not appear to be closely related to any other species, but it does appear to be remotely related to a bewildering array of unlikely families. Its tube mouth and head shape suggest that it may be related to the pipefishes and seahorses, but it also has two dorsal fins which no self-respecting syngnathid would ever have. Because the spines of the first of these dorsal fins are free of any interconnecting membrane, it might appear that I. paradoxus is a shirt-tail relative of the sticklebacks. For various other anatomical reasons ichthyologists have accused the Paradox Fish of being related to the trumpetfishes (Aulostomidae), Ghost Pipefishes (Solenostomidae), and the Tubenoses (Aulorhynchidae).

I was intrigued by this seeming evolutionary one-off. And I was fascinated by the concept, new for me at the time, of ichthyologists working to find each species’ place in the tree of life. Humans like to classify and organize things, and here was a fish that defied classification!

Today, the Paradox Fish — now called Armored Sticklebacks, with the addition of two additional species described in 1999 — remains an evolutionary enigma. Some ichthyologists provisionally place it, based on molecular and genomic data, in the order Synbranchiformes, which includes the swamp eels of South America and the freshwater spiny eels of Africa. This is the placement I follow in the ETYFish Project.

Fittingly, perhaps, the etymology of the name “Indostomus paradoxus” defies an easy or satisfactory explanation as well. Described as a new genus and species in a new family (Indostomidae) in 1929 by B. Prashad and D. D. Mukerji of the Zoological Survey of India, the authors did not explain the meaning of either half of the name. “Stomus” means “mouth” and may in this case refer to the fish’s tube-like mouth. But since the authors believe it is related to the pipefish genus Solenostomus (“soleno” meaning “pipe,” or tube), “stomus” could be their shorthand way of indicating its presumed relationship with Solenostomus.

The prefix “Indo” is a bigger mystery. I examined several possibilities:

-

- According to Brown’s “Composition of Scientific Words,” “indo,” derived from the Latin “inditus,” can mean “put, set, place into or upon, apply to, impose.” But that translation in conjunction with “stoma” makes no apparent sense (“put mouth”). One aquarium website says that the name refers to the fish’s very small mouth, but I cannot find any “indo-” adjectives that connote size.

- “Indo” often refers to India. Although this fish was described by Indian biologists writing in an Indian journal, it occurs in Burma (Myanmar), not India.

- “Indo” may refer to the Indian Ocean. The southwest coast of Myanmar occurs on the northeast portion of the Indian Ocean (specifically, the Bay of Bengal). But the fish’s type locality, Lake Indawgyi, occurs far inland in Kachin state, bordered by Tibet and China. However, Prashad and Mukerji present the possibility that Lake Indawgyi was connected to the bay of Bengal in earlier geological times, which could explain the presence of a “marine relict” (their term) in an inland freshwater lake.

- Speaking of Lake Indawgyi, could “Indo” be a variant of misspelling of “Inda”? According to Prashad and Mukerji, “Indawgyi” means “the large Royal lake” (in = lake, daw = royal, guy = large).

- Could “Indo” refer to the Indian subcontinent at large? Maybe. Today, Myanmar is not considered part of the Indian subcontinent. I do not know how geologists classified the country in 1929.

- Indochina or the Indochinese Peninsula? Maybe.

- Indo-Australian archipelago? No. Myanmar is not included.

- Indonesia? No. Different country entirely.

Stumped, I asked my friend, ichthyologist Ronald Fricke. He suggested that “Indo” refers to “Indian” because Burma in 1929 was part of British India. And so my posted etymology for Indostomus reads: “etymology not explained, perhaps Indo-, Indian, referring to type locality in Burma (now Myanmar), then part of British India; stomus, mouth, but possibly referring to its presumed closest relative [at the time], the pipefish genus Solenostomus (Syngnathiformes: Solenostomidae), i.e., an Indian Solenostomus.”

Prashad and Mukerji were equally vague about the specific name “paradoxus.” Today the word “paradox” usually refers to a seemingly absurd or self-contradictory proposition that often leads to a senseless, logically unacceptable conclusion. But the term as used here is likely derived from the Greek “paradoxos,” which means “strange or contrary to expectation.” One can guess that the authors did not expect to find what they described as a “marine relict” pipefish living in an inland freshwater lake in Burma. Or maybe they thought the fish’s combination of characters — the small tubular mouth of a pipefish, the dorsal spines of a stickleback — was uniquely and intriguingly strange.

14-year-old Ulf Hannerz appearing on “Kvitt eller dubbelt” with host Nils Erik Bæhrendtz, January 12, 1957.

12 June

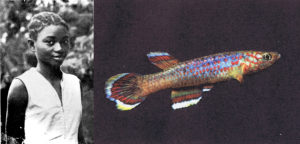

Poropanchax hannerzi and the 10,000 Kronor Question

9 FEB. 2025 UPDATE: Poropanchax hannerzi is now considered a synonym of P. luxophthalmus. In 1968, killifish legend Jørgen J. Scheel (1916- 1989) described Aplocheilichthys macrophthalmus hannerzi, now known as Poropanchax hannerzi. Scheel named the killifish in honor of a young Swedish tropical-fish hobbyist named Ulf Hannerz (b. 1942), who collected live specimens in Nigeria and sent them to Scheel in 1961. Hannerz went on to have a distinguished career as a social anthropologist specializing in urban societies, local media cultures, transnational cultural processes, and globalization.