NAMES OF THE WEEK from: 2013 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 2023 2024

31 December 2014

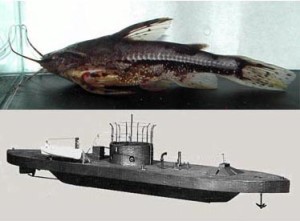

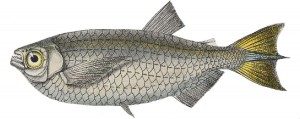

Cope headscratcher #8: Amblydoras monitor

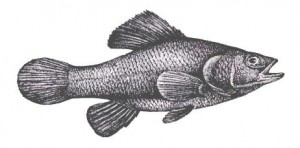

Continuing our series of enigmatic names proposed by the American ichthyologist-herpetologist-paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope, we turn to the doradid (or thorny) catfish Amblydoras monitor of the upper Amazon River basin of Brazil, Colombia and Peru. Did Cope name this catfish after a monitor lizard?

As was his custom, Cope did not explain the meaning of the specific epithet in the published version of his description. But when he orally presented his paper (or an abstract of it) to the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, he gave us the clue we needed, which the secretary of the Academy fortunately recorded and published:

PROF. COPE demonstrated some anatomical points of importance in the classification of some of the Siluroids of the Amazon, noticing first those which have no swimming-bladder … [and] Others having huge swim-bladders, [and a] gun-boat style of shape … indicated as “Zathorax.”

Zathorax is the generic name Cope proposed to accompany the specific name monitor proposed 160 pages later in the same publication.

Do you see a resemblance? Top: Amblydoras monitor (courtesy www.scotcat.com). Bottom: a model of the USS Monitor (public domain).

The descriptive phrase “gun-boat style of shape” is the clue we needed. A “monitor” is a class of small warships that carry disproportionately large guns. The first monitor was the USS Monitor, an ironclad warship commissioned in 1862 during the U.S. Civil War. It was a distinctive and revolutionary design that received much attention in the press at the time. Our guess is that Cope was comparing the catfish’s bony shields to the Monitor’s ironclad hull.

Supporting our guess is the fact that in the same paper Cope compared another doradid catfish, Physopyxis lyra, to a “miniature iron-clad with mast and outriggers.”

Etheostoma hopkinsi binotatum, Stevens Creek tributary (Edgefield County, SC). Photo by Dustin Smith. Courtesy: North American Native Fishes Association (www.nanfa.org).

24 December 2014

Etheostoma hopkinsi binotatum Bailey & Richards 1963

Today is Christmas Eve, which we commemorate with the North American percid subspecies Etheostoma hopkinsi binotatum, commonly known as both the Christmas-Eve Darter and the Hanukkah Darter.

The nominate subspecies, E. h. hopkinsi, was described by Fowler in 1945. It occurs in the Ogeechee and Altamaha River drainages of Georgia. Its name honors Milton N. Hopkins, Jr. (1926-2007), who collected the type. Hopkins was a farmer in southern Georgia, as well as a conservationist, naturalist, author, and member of the Georgia Ornithological Society. Its vernacular name, Christmas Darter, was proposed by Reeve M. Bailey and William J. Richards, when they split the species into two subspecies in 1963. The name refers to the “gay decoration of the body with symbolic red and green bands.”

The second subspecies, E. h. binotatum, occurs in the Savannah River drainage of Georgia and South Carolina. Its trinomial (bi-, two; notatus, marked) refers to two large diagnostic spots on the nape. “It is likely that these are recognition marks of importance to the fish as well as to the systematist,” the authors wrote.

Bailey and Richards did not propose a common name for this taxon. Since it is a subspecies of the Christmas Darter, someone (we don’t know who or when), cleverly suggested calling it the Christmas-Eve Darter, a name that always elicits a smile. Then, in 2011, Tom Near et al. listed Etheostoma binotatum as a full species with a new common name: Hanukkah Darter.

Christmas Eve or Hanukkah — it doesn’t matter to us. We hope your December 24th — and every day this holiday season — is full of fishes, frolic and fun.

17 December 2014

17 December 2014

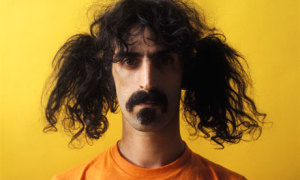

Zappa Murdy 1989

This Sunday, 21 December, marks the 74th birthday of American rock musician and composer Frank Zappa. Ichthyologist Edward O. Murdy must be a big Zappa fan, because he named a monotypic genus of mudskipper goby after the musician in 1989. The one species is Zappa confluentus (Roberts 1978), which occurs on muddy riverbanks and mud flats in Papua New Guinea.

In selecting Zappa as the name, Murdy wrote: “The generic name is in honour of Frank Zappa for his articulate and sagacious defense of the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.”

According to Wikipedia, “His lyrics—often humorously—reflected his iconoclastic view of established social and political processes, structures and movements. He was a strident critic of mainstream education and organized religion, and a forthright and passionate advocate for freedom of speech, self-education, political participation and the abolition of censorship.”

Zappa died from prostate cancer on Saturday, December 4, 1993.

Some personal trivia: Zappa was born in Baltimore, Maryland, USA, home of the The ETYFish Project. And our (CS) Latin professor in college was Frank Zappa’s uncle! (“I went to a few of his concerts, and there was a lot of marijuana,” he fondly remembered.)

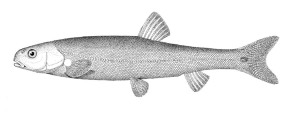

Evarra eigenmanni, type species of Evarra. From: Woolman, A. J. 1894. Report on a collection of fishes from the rivers of central and northern Mexico. Bulletin of the U. S. Fish Commission v. 14 (art. 8) (for 1894): 55-66, Pl. 2.

10 December 2014

Evarra Woolman 1894

Woolman did not indicate why he named this genus of Mexican minnows Evarra in 1894. But many authorities, including Jordan & Evermann, presumed it had something to with Rudyard Kipling’s poem, “Evarra and His Gods,” first published in 1890. So we asked the Kipling Society if they had any information or insights on the name. As it turns out, Kipling scholars are at a loss to explain the provenance of the name too, and were looking for help from an ichthyologist when our query was received!

With the help of the Kipling Society, this is what we know: Evarra is a Mexican forename that achieved some level of fame in Kipling’s poem, which drew upon an Indian (India, not Amerindian) tradition of producing idols from oddly shaped stones, trees and other objects into “gods” that are recognizably in the image of the maker, who, in the verse, is named Evarra, a “maker of gods in lands beyond the sea.”

Our best guess is that Woolman simply gave a nice-sounding Mexican name to a uniquely Mexican genus of fishes. But who knows, maybe there was a more literary connection between the poem and the minnow that we’re not seeing. You can read the poem here:

Unfortunately, the secret of Woolman’s selection is probably lost forever, just as the genus is in the wild. All three species of Evarra were near extinction in the 1950s, and were officially declared extinct by 1983. Agriculture, persistent groundwater removal, and the development of México City and its suburbs combined to destroy the area’s lakes, spring-fed ponds and canals, and the unique minnows that lived in them.

The only place Evarra now exists is with the gods.

3 December 2014

Otocinclus batmani Lehmann A. 2006

Holy Catfish, Batman!

This small loricariid is known from its type locality, a small stream tributary to the Río Puré in Colombia, and from two creeks emptying into the Río Amazonas near Iquitos, in the upper Amazon River basin of Peru.

Can you see why it’s named for the Caped Crusader, aka the Dark Knight, aka Bruce Wayne, of Gotham City?

The North American Paddlefish has many gill rakers, but is not named for them. Photo by Jan Jeffrey Hoover.

26 November 2014

Polyodon Lacepède 1797

Polyodon is the genus of the North American Paddlefish, Polyodon spathula. Many references will inform you that poly– means many and odon– means tooth. They are correct. They will also tell you that the name refers to the Paddlefish’s numerous gill rakers. They are wrong. Even the recently published Freshwater Fishes of North America (Johns Hopkins University Press), which promises to be the go-to reference for North American ichthyology, has it wrong.

While it is true that the Paddlefish has many gill rakers which it uses to filter zooplankton from the water, gill rakers were not mentioned in Lacepède’s description. Here is a translation of the pertinent section:

The paddlefish is indeed a cartilaginous fish that has many relationships with the sharks, but it differs in that it has a gill opening on each side of the body, covered with a very large opercle without a membrane. It is close, it is true, [to] Acipenser (sturgeon), but it is distinguished by the presence of many teeth in the paddlefish, and zero in Acipenser.

But wait! The North American Paddlefish doesn’t have teeth, right?

Adults don’t, but juveniles do.

According to David Starr Jordan (1882) , Lacepède’s description was made up from numerous young specimens preserved in the French Museum of Natural History. A few years later, others proposed changing the genus name to Spatularia (referring to its spatulate paddle, or rostrum), on the grounds that Polyodon was an inappropriate name since the adults do not have teeth. (In fact, adult paddlefish were once described as a different, toothless species, Polyodon edentula.) But as Jordan concluded:

“There is, however, no good ground for setting aside Polyodon, even if Spatularia seems a more pleasing name. The fish does have many teeth, even if they ultimately fall out, and Polyodon it must remain.”

19 November 2014

Platygillellus bussingi Dawson 1974

Yesterday, we learned the very sad news that William (Bill) A. Bussing died Monday afternoon in a car accident in Costa Rica. Bussing was a passenger in the car, which apparently skidded off the road, struck a utility pole, and then collided with a metal traffic barrier. Part of the metal structure struck the passenger’s side door where Bussing was riding. The driver survived but we do not know the extent of his injuries nor why the accident occurred. Bill Bussing was the preeminent authority on the fishes of Costa Rica.

Born in 1933, Bussing was raised in Los Angeles. He was an avid aquarist from early on, an interest that led him to the University of Miami and Universidad de Guadalajara (Mexico), where he helped research fish grazing at Eniwetok Atoll and received an Inter-American Cultural Convention Scholarship (1962-63) to study the ecology of the fishes of Rio Puerto Viejo, Costa Rica. He obtained his Master’s degree from the University of Southern California in 1965, with a thesis on the bathypelagic fishes in the eastern Pacific.

In 1966, Bussing returned to Costa Rica, where he taught ichthyology and marine biology at the Universidad de Costa Rica (UCR). His research at first centered on freshwater fishes in Costa Rica and other Central American countries, but then expanded to include marine fishes from both coasts of Costa Rica and Isla del Coco. He retired from UCR in 1991 but continued as Curator of Fishes. He described over 50 species of fishes from Costa Rica and has had six species named in his honor. The first of these was a sand stargazer (Dactyloscopidae), Platygillellus bussingi, from the Pacific coast of Costa Rica and Panama. The author honored Bussing for “his many courtesies” and for making specimens available for study.

Bill Bussing was 81.

12 November 2014

Parachiloglanis bhutanensis Thoni & Gurung 2014

Yesterday, 11 November, marked the 59th birthday of Jigme Singye Wangchuck, king of Bhutan from 1972 to 2006. Bhutan is a landlocked country bordered by China, India and Nepal at the eastern end of the Himalayas. The king’s birthday is a national holiday in Bhutan, called Constitution Day; under this king and at his bequest, the Bhutan’s constitution was enacted, transitioning from an absolute monarchy to a constitutional monarchy in 2008.

We commemorate this holiday with news of the first species scientifically described from within Bhutan, the Khaling Torrent Catfish, Parachiloglanis bhutanensis. The new species, a member of the Hillstream Catfish family Sisoridae, was recently described in the journal Zootaxa, 3869 (3): 306–312.

The meaning of the generic name Parachiloglanis, proposed by Wu, He & Chu in 1981, is unclear; we believe it means para-, near and chiloglanis, perhaps an abridgement of Euchiloglanis (now Chimarrichthys), in which the type species (P. hodgarti) had been placed. However, the name could also refer to similar mouth/lip structure with the African mochokid catfish genus Chiloglanis. The meaning of the specific name, however, is unambiguous: – ensis is a suffix that denotes place, in this case, Bhutan, the only country where the species occurs.

The common name, Khaling Torrent Catfish, refers to the village of Khaling, about 1 km east of where the catfish was discovered, in a high-velocity, small-order stream at 2211 m above sea level. The catfish adheres to the bottom side of boulders, favoring areas of cascades and white water rather than pools.

5 November 2014

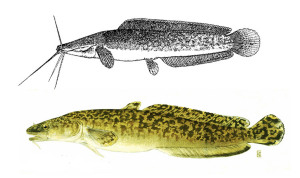

Clarias

Here’s an interesting case of one etymologically mysterious name — Clarias — applying to two markedly different catfishes: Clarias, a genus of air-breathing (or walking) catfishes from Africa and Asia, and Synodontis clarias, the Upside-Down, or Squeaker Catfish, of Africa. We believe we understand how the genus (Clarias) came by its name. What we don’t understand is why the same epithet was given to Silurus (now Synodontis) clarias as well.

Initially, we reported that the meaning of the clariid genus name Clarias is unknown but could be derived from the Greek chlaros, meaning lively, referring to the extreme hardiness of clariid catfishes and/or their ability to live for a long time out of water (and, in some cases, actually move across land). Most contemporary sources give this explanation, although catfish experts Isbrücker & Nijssen (1984) suggested, without explanation, that the name might be derived from callarias, the Latin word for cod (derived from the Greek kallarias).

A few weeks ago, our good friend Erwin Schraml alerted us to the fact that Bloch & Schneider changed the name of Silurus clarias to Silurus callarias in 1801. They believed that the former name was a misspelling of the latter and sought to issue a correction. Today, S. callarias is considered to be an unneeded replacement name for S. clarias. But now we had some evidence that clarias might mean something other than “lively.” It might mean “cod.” But why?

We kept looking and eventually came across what we believe is the earliest account of a clariid catfish in scientific literature: De aquatilibus libri duo (1553) by the Renaissance scholar and traveler Pierre Belon (1517-1564).

De aquatilibus was based largely on Belon’s own observations of fishes and other animals in France, the Mediterranean, and the Levant, a region that historically included Syria, Cyprus, Greece, Turkey, and Egypt. Among the fishes described in his book were three given the same forename: “Claria marina” (“cod of the sea,” probably the Common Ling, Molva molva); “Claria fluviatilis” (“cod of the river,” probably the Burbot, Lota lota); and “Claria nilotica” (“cod of the Nile”). This Nile species is now known as Clarias anguillaris, the type species of the genus.

Somewhere along the way, “Claria” became “Clarias.” Gronow introduced this spelling in 1763 as the generic name for air-breathing (or walking) catfishes. But since Gronow did not follow the principles of binominal nomenclature, he is not considered the author of the name. Instead, Clarias dates to Scopoli (1777), who republished many of Gronow’s names but in a binominally valid way. To confuse matters even more, Scopoli spelled Clarias with an “h” — Chlarias. Some regard this spelling as a typo. Others regard it as proof that the name derives from chlaros, meaning lively. Unfortunately, neither author did us the favor of indicating what they believed Clarias (or Chlarias) to mean.

It’s easy to see how a 16th-century naturalist might believe these two fishes are related. Top: Clarias anguillaris (courtesy: FishBase). Bottom: Lota lota (courtesy: New York State Department of Environmental Conservation).

Valenciennes introduced the callarias/cod explanation in volume 15 of Histoire Naturelle des Poissons in 1840. He, like us, was confused by how two different catfishes were known by the same name and attempted to sort things out. On page 170, he mentions that “clarias” is a corruption of “callarias.” Later, on page 360, he mentions that Belon compared his “Claria nilotica” with “la lote de France” (lote, of course, referring to Lota lota, the codlike Burbot). Look at a photo of Lota lota; it does indeed resemble Clarias anguillaris. Based on this evidence, we can confidently say that the name Clarias as applied to catfishes of the family Clariidae does not mean “lively.” It means cod or codlike.

Unfortunately, we cannot confidently say how the same name applies to the conspicuously un-codlike Synodontis clarias. The name was coined by Linnaeus’ student Fredrik Hasselquist (1722-1752) in a posthumous 1757 publication that Linnaeus edited. The name became officially available for nomenclatural purposes when Linnaeus listed it in the 10th edition of his Systema Naturae of 1758. Again, neither author did us the favor of indicating what they believed clarias to mean.

Valenciennes suggested an explanation, albeit one that’s somewhat convoluted. Since both “Claria nilotica” (Clarias anguillaris) and Synodontis clarias were described from specimens that originated from the Nile, he guessed that Hasselquist selected clarias for his Nile catfish simply because Belon used the similar “claria” name for his. (And, yes, Hasselquist was aware that Belon’s “cod” from the Nile was actually a catfish; it’s the very next species mentioned in his book.)

Erwin Schraml suggested another possible explanation for the Synodontis clarias name: that clarias is derived from clarus, which usually means bright or clear (e.g., clarity) but can also mean loud or clangorous (e.g., clarion), in which case the name could refer to this catfish’s ability to make stridulatory sounds through its pectoral fins when handled or disturbed (hence the vernacular name Squeaker). This explanation would have more credence if Hasselquist had mentioned the Squeaker’s seemingly noteworthy squeaker skills in his description. Alas, he did not.

29 October 2014

Percina crypta Freeman, Freeman & Burkhead 2008

This week we commemorate the Western holiday of Halloween (31 October), by featuring the Halloween Darter, Percina crypta. This darter (Percidae) is endemic to the Chattahoochee and Flint River systems in Georgia and Alabama, USA. Its specific name, crypta, meaning hidden or concealed, refers to its close similarity in appearance to its sympatric congener, P. nigrofasicata. The common name refers to the striking black and orange coloration of nuptial individuals, colors associated with Halloween, a Celtic festival adopted by the Roman Catholic Church as the eve of All Saints Day.

This week we commemorate the Western holiday of Halloween (31 October), by featuring the Halloween Darter, Percina crypta. This darter (Percidae) is endemic to the Chattahoochee and Flint River systems in Georgia and Alabama, USA. Its specific name, crypta, meaning hidden or concealed, refers to its close similarity in appearance to its sympatric congener, P. nigrofasicata. The common name refers to the striking black and orange coloration of nuptial individuals, colors associated with Halloween, a Celtic festival adopted by the Roman Catholic Church as the eve of All Saints Day.

Learn more about the fish, and see a photo of it, here.

22 October 2014

Fiordichthys slartibartfasti Paulin 1995

Fans of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy will quickly recognize this name. Marine biologist Chris Paulin named this viviparous brotula (Bythitidae) from the Fiordland region of New Zealand after Slartibartfast, a designer of fjords who appeared in the first and third books of Douglas Adams’ series.

Paulin also mined Hitchhiker’s for the name of a second New Zealand bythitid. Bidenichthys beeblebroxi, which has a color pattern resembling that of a second head, presumably to confuse would-be predators, is named for the bicephalic Zaphod Beeblebrox. [Update 19 Sept. 2018: B. beeblebroxi is now considered a junior synonym of B. consobrinus.]

Don’t forget to bring a towel!

15 October 2014

15 October 2014

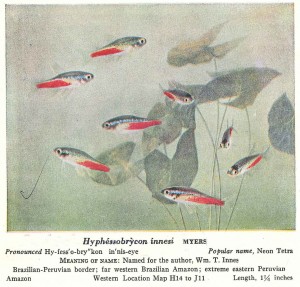

Paracheirodon innesi (Myers 1936)

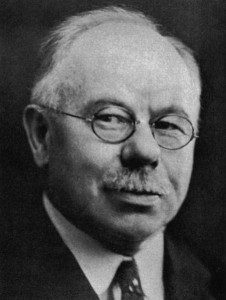

This week we’re celebrating the one-year anniversary of The ETYFish Project by honoring the man who sparked my (CS) interest in fish name derivations: American aquarist, author, photographer and publisher, William T. Innes (1874-1969).

Growing up in the late 1960s and early 1970s, our basement was home to several community tank aquariums. My father dabbled in keeping tropical fishes, as did my oldest brother, who eventually tried his hand at saltwater aquaria when that hobby was still in its early days. As a young boy I enjoyed watching the fishes. But I also enjoyed thumbing through the pages of our one and only aquarium-hobby reference — a 1950s edition of Innes’ classic book Exotic Aquarium Fishes. (I can’t tell you the exact date or edition; the copyright pages fell out a long time ago.)

The clarity of Innes’ prose and the quality of the printing amaze me to this day. I love the book’s dark green leatherette cover featuring an image of three Rasbora (now Trigonostigma) heteromorpha stamped in gold. I love the glossy pages and delicate typography. And I love Innes’ photography, austere black-and-white plates for most species, and hand-painted photos for many of the more colorful ones, including the Neon Tetra, shown here.

I also loved the fact that Innes provided name etymologies for the species he included. Not only did I learn (at a very early age) that each and every fish had a unique Latin name, but I also learned that these names had specific meanings. Innes also provided a pronunciation guide. I enjoyed, as a precocious young kid, going to the aquarium store and asking the clerk for Lebistes reticulatus (now Poecilia reticulata) instead of just saying Guppy.

Three fishes have been named after Innes, none more famous than the aquarium staple, the Neon Tetra. Innes sent specimens of the (then) rare species to ichthyologist George S. Myers of the Smithsonian Institution for identification. Myers named “this gorgeous little fish” Hyphessobrycon (now Paracheirodon) innesi in honor of his good friend.

I still have my father’s copy of Innes’ book. The binding is shot. Several pages are missing. At some point I had apparently inked a check mark on the photo of those species that were in my aquaria at the time.

Save for a few Matchbox cars, it’s my last surviving relic of a childhood that ended over 40 years ago. And the inspiration for a major part of my life today.

8 October 2014

Scriptaphyosemion roloffi (Roloff 1936)

Naming a species after oneself — while not explicitly prohibited under the rules of zoological nomenclature — is exceedingly frowned upon. However, there are several instances in ichthyological nomenclature in which it appears that a scientist has done just that, but upon a closer examination it is revealed that a different scientist coined the name (either on a museum label or in a manuscript), which the honoree unintentionally made available in one of his own publications. Here is one example:

In 1936, German ichthyologist-herpetologist Ernst Ahl prepared a description of the African killifish Aphyosemion roloffi, which he named after his good friend, German aquarist Erhard Roloff, who collected the type in Sierra Leone. Ahl apparently shared his manuscript with Roloff, who copied some of Ahl’s data and published it in a German aquarium magazine Wochenschrift für Aquarien- und Terrarienkunde a few months before Ahl’s description appeared in the scientific journal Mitteilungen aus dem Zoologischen Museum. Roloff was not stealing credit for Ahl’s description. He simply “jumped the gun.” Unfortunately, Roloff’s article has priority over Ahl’s paper and therefore the name dates to Roloff as the author. (The rules have since been changed to prevent this from happening.)

Normally, our story would end there. But the name Aphyosemion roloffi has taken on a rather bizarre life of its own. Over the years it has been subject to a number of generic reassignments and permutations, creating (at least temporarily) one of the most striking name/author combinations in zoological nomenclature.

In 1966, Roloff was honored again, this time by H. S. Clausen, who proposed the genus Roloffia for most species of Aphyosemion that occur west of the Dahomey Gap in Southwest Africa. In 1967, Clausen moved A. roloffi to Roloffia, thus creating the unintentionally humorous name …

Roloffia roloffi (Roloff 1936)

… although it should be noted that Clausen believed Ahl was the author, not Roloff.

In 1971, Roloff himself decided that R. roloffi might represent two subspecies. He floated the name Roloffia roloffi hastingsi in an aquarium publication but did not provide a description (a nomen nudum). Had “hastingsi” been a valid name, then the nominate form would have been called …

Roloffia roloffi roloffi (Roloff 1936) (!)

Roloffia is now considered a junior objective synonym of Callopanchax Myers 1933. And Aphyosemion roloffi was assigned to the subgenus Scriptaphyosemion in 1987, which was elevated to full genus in 1999.

Scriptaphyosemion roloffi is a fine name. But we can’t help but liking how Roloffia roloffi (Roloff) rolls off the tongue.

1 October 2014

Cope headscratcher #7: Platygobio gracilis gulonellus

Every time we work on one of these Cope headscratchers, we feel like a homicide detective returning to a cold case. Maybe we’ll find a clue or follow a lead we didn’t notice the previous times we had looked. This time we did. Unfortunately, the meaning of the name, like so many others that Cope introduced to science, remains as elusive as ever.

Platygobio gracilis gulonellus is a subspecies of Flathead Chub, P. g. gracilis, of central North America. The nominate subspecies, with a more pointed head, occurs in the northern and eastern parts of its range, usually in large rivers. The second subspecies, with a more rounded snout, occurs to the south and west, usually in smaller streams. Cope described this form as Pogonichthys (subgenus Platygobio) gulonellus in 1865. The brief description (shown here in its entirety) appeared in a footnote. Cope compared the new species with P. communis, now a junior synonym of P. gracilis gracilis.

–ellus, we know, is a diminutive suffix, usually applied to an adjective to connote that something is smaller or the smallest of its kind. Gulon– we’re not so sure about. At first we thought it was from the Latin gula, meaning throat, i.e., small throat. Cope mentioned the breadth between the eye is shorter in gulonellus than in communis. Is this what we meant by “small throat”? With no other evidence before us, that was our best (though very weak) guess.

When we reopened the “case” we noticed an overlooked clue: Cope had named a characin Cynopotamus (now Galeocharax) gulo in 1870. Again, as was his custom, Cope did not explain what the name meant. But gulo is a different word than gula. It is Latin for epicure or glutton. In this case, we surmise it refers to the characin’s large mouth filled with needle-sharp teeth used to hold prey.

So, with this new translation of the name, could gulonellus mean “small glutton”? And what might it mean?

Only Cope knows for sure. And he’s not talking.

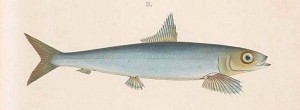

Etrumeus micropus. From: Temminck, C. J. and H. Schlegel. 1846. Pisces. In: Fauna Japonica, sive descriptio animalium quae in itinere per Japoniam suscepto annis 1823-30 collegit, notis observationibus et adumbrationibus illustravit P. F. de Siebold. Parts 10-14: 173-269.

24 September 2014

Etrumeus micropus (Temminck & Schlegel 1846)

Many times we’ve revealed how ichthyologists have mistranslated the Latin names of fishes, leading to incorrect or misleading etymological explanations. While we’d like to think that our explanations are 100% correct, we’re not immune to slipping up ourselves.

This is how we initially reported the etymology of the specifc name of Etrumeus micropus, a Round Herring from Japan:

micro-, small; ops, eye, a misnomer since eye is large, a fact that mentioned in description (perhaps a misprint of macropus?)

In retrospect, the fact that our translation of the name was not corroborated by the written description should have tipped us off that something was amiss. What’s more, we should have realized that “small eye” is microps, not micropus. Instead, we overlooked the fact that in some scientific names for fishes, –opus is derived from pous, which means “foot” and applies to fins, usually the ventral (or pelvic) fins, as in these two examples:

Nannocharax procatopus Boulenger 1920 pro-, forward; cato-, low; pous, foot, referring to origin of ventral fins (“low feet”) well in front of origin of dorsal fin

Xenurobrycon macropus Myers & Miranda Ribeiro 1945 macro-, long; pous, foot, referring to elongate pelvic fins of males

We discovered the error while researching the specific-name etymology of the ariid catfish Cathorops melanopus, which we initially translated as “black eye.” When consulting Günther’s original description, we saw that the name instead referred to the fish’s black-edged ventral fins. Had we confused “opus” and “ops” in previous entries? Yes, we had.

Upon realizing the error, we returned to Temminck & Schlegel’s Fauna Japonica for confirmation: Sure enough, we found it: “Les ventrales sont petites; elles commencent à peu de distance derrière l’aplomb de la fin de la dorsale.” Translation: The ventrals are small; they begin a short distance behind the vertical-ness of the end of the dorsal.

We regret the error. We celebrate the correction!

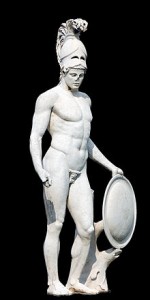

Ares is the Greek god of war. His name has nothing to do with ariid catfishes. (Courtesy: Wikipedia)

17 September 2014

Arius Valenciennes 1840

Arius is the type genus of the Sea Catfish family Ariidae. Google “Arius etymology” and you will be directed to several pages that provide the same derivation of the name. Trouble is, they’re wrong.

According to FishBase, Arius is derived from the Greek arios or areios, meaning warlike or bellicose. The source for this information is an unpublished 2002 document from one P. Romero called “An etymological dictionary of taxonomy.” According to FishBase, “This dictonary [sic] resides in a database and will eventually be published. Etymology of names was made available to FishBase in spreadsheets.”

We’ve found that many name etymologies credited to this document are incorrect, serving as a major source of misinformation picked up by other websites. For example, the excellent aquarium website Planet Catfish repeats FishBase’s erroneous Arius etymology, adding that the name refers to the genus’ well-developed fin spines. One could also apply this warlike allusion to the catfish’s prominent occipital process, referred to by many 19th-century ichthyologists as a “helmet.” Donning a helmet and armed with dangerous fin spines, ariid catfishes can indeed be called warlike or bellicose. But that is not what the name means.

As we’ve stated numerous times before, one must always consult the original description to determine the meaning of a name. (Apparently, Romero did not.) In this case, we need to consult two original descriptions, since the genus name Arius is tautonymous with Pimelodus arius (now Arius arius) described by Hamilton-Buchanan (or simply Hamilton) in his 1822 book An Account of the Fishes Found in the River Ganges and its Branches. Valenciennes was quite clear on this point when he proposed the genus in 1840. Writing in the 15th volume of Histoire Naturelle des Poissons (page 53), he admitted that “Le nom que je leur donne est emprunté à l’un des silures de M. Hamilton Buchanan …” (“The name I give them is borrowed from the catfish of Mr. Hamilton Buchanan …”).

While Hamilton did not explicitly state what Arius means, he often latinized local Bengali names for many of the fishes he introduced to science. On page 170 of his Gangetic tome, he mentions that the local name of Pimelodus arius is “Ari gagora.” Arius is clearly a latinization of Ari.

What did “Ari” mean originally? We do not know. But we do know that Arius is not derived from the Greek words for warlike or bellicose, as fitting as that explanation might be.

10 September 2014

Latimeria menadoensis Pouyaud, Wirjoatmodjo, Rachmatika, Tjakrawidjaja, Hadiaty & Hadie 1999

This name is a case of scientific piracy.

In September 1987, zoologist Mark Erdmann and his fiancée Arnaz Mehta were touring a Sulawesi fish market when Arnaz spotted an unusual fish draped over a cart. Mark immediately recognized it as a coelacanth, although it was far out of range (~1000 miles) from the famous coelacanth, Latimeria chalumnae, discovered off the east coast of South Africa in 1938. Mark took photographs but, lacking a freezer, did not procure the specimen.

Suspecting that there was an Indonesian population of coelacanths, Mark secured funding from the National Geographic Society to search for another specimen. He found one a year later, barely alive after being caught in a gill net. Mark and Arnaz photographed the fish, took tissue samples and stored them in liquid nitrogen, then, after it died, took it to the Zoological Museum in Bogor, just south of Jakarta, where it could be properly examined and preserved. Mark announced his discovery in the 24 September 1998 issue of Nature, but was not yet sure on whether the Indonesian specimen represented a new species. More study was needed.

Meanwhile, Laurent Pouyard, a French scientist specializing in catfishes in Jakarta, teamed up with five local Indonesian scientists, and announced that Erdmann’s specimen was indeed a different species and went ahead and named it L. menadoensis, referring to Manado Tua Island, the type locality. Erdmann was barely mentioned in the description — a citation to his Nature article, buried in the references.

“We can only imagine Mark Erdmann’s anger,” wrote Peter Forey in his 2009 book Coelacanth: Portrait of a Living Fossil. “For well over a year he had been scouring northern Sulawesi for a coelacanth; he had found one; he had carefully preserved it for future study, only to find that others had coolly walked in and helped themselves to name his treasure. This is scientific piracy writ large. In scientific circles this is definitely bad behavior. Those who make discoveries have, at least, the initial rights to study and to have their name attached.”

But that’s only part of the story.

Shortly after Erdmann announced his discovery, a cryptozoology website announced that a French scientist had discovered the Indonesian coelacanth three years earlier, in 1995. A lobster fisheries consultant named George Serre allegedly discovered the fish trapped in a lobster pot. According to Serre, he photographed the specimen and sent it to the Indonesian Fishery Institution in Jakarta. But the specimen never got there and somehow Serre’s photographs were lost. But when Erdmann’s article appeared, Serre suddenly relocated his photographs and the lost specimen was allegedly “rediscovered” as well — by none other than Laurent Pouyard, the same scientist who denied Erdmann the chance to name the fish he and his fiancée had discovered.

In 2000, Pouyard, Serre and French shark taxonomist Bernard Séret wrote a letter to Nature claiming to be the first to have discovered the Indonesian coelacanth, and submitted one of Serre’s photographs as proof. But a sharp-eyed editor at Nature noticed that the specimen in Serre’s photo (allegedly from 1995) was identical in color pattern and angle to the photo submitted by Erdmann in 1998. Sure enough, Serre’s photo was a fake. Someone had manipulated Erdmann’s photo, removing the image of the fish and inserting it into a photo of a grouper and a snapper on a fishmonger’s slab.

The editors of Nature then did something totally cool — they published their own article exposing the fraud!

Lots of finger-pointing ensued after that. Pouyard and Séret claimed innocence, saying that Serre had tried to fool them. Serre claimed that someone else took the photo (someone who had since died). Pouyard’s employer launched an investigation and, according to Peter Forey, offered “severe reprimands” for his behavior.

Even the American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists got into the act, issuing a stinging (and tongue-in-cheek) resolution:

WHEREAS through a dubious demonstration of ethics by scientists from the land of Jean LaFitte and editors of otherwise respected journals, this piscine treasure was described by someone other than Erdmann and his colleagues, and

WHEREAS, there is a long history of the recognition of the original discoverer of living coelacanths in the scientific nomenclature for the new organism,

[THEREFORE] BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED THAT the assembled societies suggest an immediate redescription of the new coelacanth to redress the evil done to nomenclatural standards, and

BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED that to maintain the historical precedent established for Latimeria chalumnae, the name be changed to Latimeria arnazerdmanni.”

Of course, the name cannot be changed. But it would be nice to honor Erdmann’s fiancée (now wife) for bringing the fish to his attention, and to commemorate the fact that the discoveries of both populations of living coelacanths were made by women.

![Thaumatichthys pagidostomus. From: H. M. and L. Radcliffe. 1912. Description of a new family of pediculate fishes from Celebes. [Scientific results of the Philippine cruise of the Fisheries steamer "Albatross," 1907-1910. No. 20.]. Proceedings of the United States National Museum v. 42 (no. 1917): 579-581, Pl. 72.](https://etyfish.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Thaumatichthys-300x88.jpg)

Thaumatichthys pagidostomus. From: Smith, H. M. and L. Radcliffe. 1912. Description of a new family of pediculate fishes from Celebes. [Scientific results of the Philippine cruise of the Fisheries steamer “Albatross,” 1907-1910. No. 20.]. Proceedings of the United States National Museum v. 42 (no. 1917): 579-581, Pl. 72.

Ladies and gentlemen, the Wonderfish!

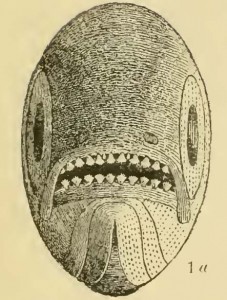

In the early part of the 20th-century, biologists began to seriously explore the mysteries of the deep sea. It seems that with every haul of their deepwater trawls, they discovered never-before-seen and bizarre creatures that evoked quite a sense of wonder about the diversity of life in the ocean. In fact, two scientists from the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries, Hugh M. Smith and Lewis Radcliffe, were so amazed about one new species of deep-sea fishes they discovered that they called it the Wonderfish: Thaumatichthys pagidostomus.

“Thauma” is Greek for a “wonder” or “marvel.” Ichthys, of course, means fish. The specific epithet is derived from pagido, meaning trap, and stomus, meaning mouth.

“In this extraordinary fish,” the authors wrote, “the head is nearly as long as the remainder of the body, and the length of the mouth is more than half that of the head. It would appear that the cavernous, elastic mouth is a trap into which the food is lured and dispatched. The light from the bulb in the roof of the mouth shines through the toothless space in the front of the upper jaw and attracts the prey which, having entered the mouth, is prevented from escaping and brought within reach of the lateral teeth by the two pair of large hinged, hooked teeth.”

While members of the family Thaumatichthyidae (two genera with seven species) are officially known as Wolftrap Anglers, we can’t help but prefer the original appellation, Wonderfishes, instead. Any fishes that live ~1400m below the surface of the ocean with a “fishing lure” inside their mouths and a Venus-flytrap-like feeding strategy is a wonderful creature indeed.

27 August 2014

Cope headscratcher #6: Labidesthes sicculus

The Brook Silverside, Labidesthes sicculus, is a common inhabitant of slow-moving rivers and lakes in North America, from the St. Lawrence and southern Great Lakes drainages to the Mississippi River basin and Gulf Coastal plains. (Despite the common name, it is not specifically found in brooks.)

Cope coined the generic name in 1870 and its meaning is clear: labidos, forceps and esthio, eat, referring to its prolonged jaws, which form a short, depressed beak. The meaning of the specific name, however, is not.

Cope proposed the name Chirostoma sicculum in 1865. He provided no explanation of its etymology. Five years later, when he reassigned the species to the new genus Labidesthes, Cope mentioned that he captured specimens of L. sicculus in pools “liable to partial desiccation in the Autumn.” This statement presumably led Jordan & Evermann in their magnum opus The Fishes of North and Middle America (1896-1900) to surmise that the name sicculus was derived from siccus, meaning dry or desiccated, and refers to Cope having found his specimens in dried ponds. This claim has been picked up by many “Fishes of …” books and many online references (including FishBase).

We find this claim doubtful since the original type was collected in Michigan and the specimens mentioned in Cope’s 1870 follow-up — presumably the ones “liable to partial desiccation” — were collected in Tennessee. Instead, we believe the name is more likely an adjectival form of sicula, dagger, referring to the fish’s sharp snout and dagger-like shape.

Check out the photo. Does the Brook Silverside look dagger-like to you?

Neochanna apoda, Brown Mudfish, 1874 illustration by Frank Clarke. Courtesy: Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Wellington, New Zealand.

20 August 2014

Neochanna Günther 1867

Neochanna is a genus of galaxiids, scaleless freshwater fishes from temperate zones of the southern hemisphere. Günther wrote that galaxiids “with regard to the development and position of their fins, remind us of the Pikes of the northern hemisphere, but in other respects (as, for instance, in their dentition and open ovaria) resemble the Salmonoids …”. Günther also noted that New Zealanders often called larger galaxiids “trout” and “rock-trout.” Yet the name Günther has coined for the genus — Neochanna — refers to neither pikes nor salmonids. While Günther never explained the etymology of the name, it clearly means new (neo-) Channa, referring to Channa, the famous (or infamous) genus of snakehead fishes from Asia.

What did Günther find Channa-like about Neochanna? He didn’t say and we didn’t have a clue … until we remembered that Günther bestowed a similar name to a genus of African clariid (air-breathing) catfishes in 1873: Channallabes. Again, Günther did not explain the name. The second part, we’re certain, is derived from allabes, the ancient Greek name for Clarias anguillaris, which is often used as a suffix for eel-shaped clariid catfishes. But what explains Günther’s choice of the prefix Channa? How do Asian snakeheads remind him of both pike- and salmonlike galaxiids of New Zealand and eellike catfishes of Africa?

When we compared the two descriptions we found the answer: Neochanna and Channallabes share a common feature, the absence of ventral (or pelvic) fins. (The specific name of the type species, N. apoda, means “without feet.”) We checked our references on snakeheads and, sure enough, many species of Channa, at least those known to Günther at the time, also lack ventral fins.

Why Günther did not explain this important similarity we cannot say. But we can say we’re now 99.99% certain he named Neochanna and Channallabes for their Channa-like absence of ventral fins.

The type locality of Xiurenbagrus dorsalis; black arrow indicates where underground water flows out, white arrow indicates location of cover of well; picture in lower left corner is the well when open. Courtesy: Jian Yang.

13 August 2014

Xiurenbagrus dorsalis Xiu, Yang & Zheng 2014

Imagine going to the basement to pump water from your well and discovering a new species swimming out of the tap! That’s pretty much what happened in Guihong, a village in Gucheng Town in Fuchuan County, in the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region of China, where, in May 2011, Jian Yang of Guangxi University’s College of Animal Science and Technology collected one specimen of a new species of blind catfish living in an underground stream with a substrate of small rocks. The stream flows across the bottom of a well. A pump is connected to the well with four feet of plastic tubing. The specimen of the new catfish, the only known specimen so far, literally came out of the tap!

The new species was recently described in Zootaxa 3835 (3): 376–380. It is a member of the Torrent Catfish family Amblycipitidae and represents the third-known species of its genus. The specific epithet dorsalis refers to the unique position of its dorsal-fin origin (posterior to vertical line at tip of pectoral fins) when compared with its congeners. The generic epithet, coined by Chen & Lundberg in 1995, is a combination of Xiuren (referring to Xiuren River, Pearl River drainage, Guangxi Province, China, type locality of X. xiuriensis, the type species), and bagrus (latinization of bagre, which, according to Marcgrave [1648], is a Portuguese word for catfish used in Brazil [possibly first applied to the marine ariid Bagre bagre], now often used as a suffix for catfish names).

6 August 2014

6 August 2014

Narcine bancroftii (Griffith & Smith 1834)

Last week we mentioned that the name of the Devil Ray genus Manta dates to British physician (and yellow fever expert) Edward Nathaniel Bancroft (1772–1842). Coincidentally, a different Edward Bancroft is associated with another ray species.

In 1834, Griffith & Smith named the Lesser Electric Ray of the Western Atlantic Torpedo bancroftii. Their description was based on a painting by Edward Bancroft (1744-1821), an American physician-naturalist and pioneer in the study of electric fishes.

Bancroft is better remembered today not for his work as a naturalist, but for serving as a double-agent spy during the American Revolution. He spied for America in England and France before the Revolution, and also for England, reporting on dealings between France and America.

His identity as a British double agent was not revealed until 1891.

30 July 2014

30 July 2014

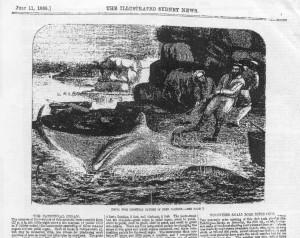

Manta alfredi (Krefft 1868)

The Reef Manta Ray (Manta alfredi) was confirmed as a valid species distinct from the Giant Oceanic Manta Ray (M. birostris) in 2009. It occurs in the tropical and subtropical Indo-Pacific, with a few records from the tropical East Atlantic. Unlike M. birostris, it tends to favor shallower coastal habitats.

The original description of M. alfredi is obscure and little-seen by modern ichthyologists and ray enthusiasts. It appeared not in a scientific journal, but in an Australian newspaper, The Illustrated Sydney News, of 11 July 1868. The author was anonymous, but Australian ichthyologist Gilbert Whitley attributed authorship to Johann Ludwig Gerard Krefft (1830-1881), who was curator of the Australian Museum at the time.*

The specific epithet honors Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh (1844-1900), who was visiting Sydney at the time this “royal fish” was caught and posed for photographs with it.

According to the Wikipedia entry on Krefft, he was fired from the Museum in 1874 and literally thrown into the street. He had accused one of the Museum’s trustees of using Museum resources to augment a private collection. The trustee in turn accused Krefft of drunkenness, falsifying attendance records, and allowing the sale of dirty postcards. Krefft filed suit and won.

The generic name Manta has an interesting story behind it as well — interesting in that nobody is 100% certain what it means. The name was first used in a nomenclaturally valid way by the British physician (and yellow fever expert) Edward Nathaniel Bancroft (1772–1842) in 1829. “Manta” is Spanish for “blanket,” reportedly a name used by pearl divers between Panama and Guayaquil to designate an enormous fish they feared could devour them after enveloping them in its vast “wings.” However, some early accounts give the name as manatia, which may be an indigenous name later abridged to manta.

* Some might say authorship should be given as “(Anonymous [Krefft] 1868)” but no one is following that convention in the current literature.

23 July 2014

23 July 2014

Crenicichla edithae Ploeg 1991

Dr. Alex Ploeg — secretary-general of both the European Pet Organisation and Ornamental Fish International, and deputy secretary of Dutch trade association Dibevo — was killed on 17 July 2014 when Malaysian Airlines flight MH17 was hit by a missile over the Ukraine while en-route from Amsterdam to Kuala Lumpur.

For his Ph.D., Dr. Ploeg studied the taxonomy of the South American pike cichlid genus Crenicichla and published the descriptions of many new species, 18 of which are considered valid today. One of the new species he described was Crenicichla edithae (now treated as a junior synonym of C. lepidota Heckel 1840) of the Río Paraguai system of Paraguay. He named it after his wife, Edith, for her support during his “scientific development.” She died, along with their son Robert and their son’s friend Robin, on the flight as well. They were on their way to a much-anticipated vacation in Asia.

We express our deepest condolences to the Ploeg’s surviving daughters, Mirjam and Sandra, and to the victims, family and friends of all 298 lives lost in this senseless tragedy.

UPDATE: 6 February 2018 A new Crenicichla species, C. ploegi Varella, Loeb, Lima & Kullander 2018, has been named in Dr. Ploeg’s honor.

16 July 2014

16 July 2014

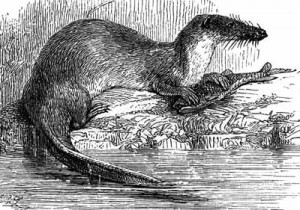

Cope headscratcher #5: Enteromius potamogalis

Edward Drinker Cope apparently took a perverse delight in coining names with elusive or enigmatic meanings known only to him. With a little help from the Internet, we were able to figure this one out in a couple of minutes.

Cope described this cyprinid from Equatorial Guinea in 1867. The specific name means “river weasel” (potamos, river; galeus, weasel). As was his custom, Cope did not explain the name, nor are there any attributes in his description that might apply to this curious epithet.

Cope did provide one clue. “This species was procured,” he wrote, “by the African traveller, P. B. Duchaillu, in streams and rivulets fifty to sixty miles north of the equator, and the same distance from the ocean.”

We recognized the name. Paul Belloni Du Chaillu (1831-1903) was one of the most- famous explorer-zoologist-anthropologists of his time. He was the first European to confirm the existence of gorillas and the pygmy people of central Africa. His books were bestsellers. So we wondered if Du Chaillu might have mentioned this fish in one of his African travel memoirs.

A few clicks later and we were able to download a copy of Du Chaillu’s A Journey to Ashango-land: and Further Penetration into Equatorial Africa, published in 1867, the same year as Cope’s description of Enteromius potamogalis. We didn’t need to read the book for the answer, for on the front cover is an illustration of the piscivorous Giant Otter Shrew (Potamogale velox) of central Africa, on the bank of a river with a large barb-like fish in its forepaws. Du Chaillu had scientifically described Potamogale velox (note the generic name) in 1860.

So it appears that Cope named E. potamogalis in honor of the person who first collected the species. But for reasons known only to Cope, he concealed Du Chaillu’s identity by naming it after one of Du Chaillu’s other discoveries, the Giant Otter Shrew, whose generic name translates as “river weasel.”

From: Sparks, J. S. and P. Chakrabarty. 2012. Revision of the endemic Malagasy cavefish genus Typhleotris (Teleostei: Gobiiformes: Milyeringidae), with discussion of its phylogenetic placement and description of a new species. American Museum Novitates No. 3764: 1-28.

9 July 2014

Typhleotris mararybe Sparks & Chakrabarty 2012

This name is sick.

In 2012, a new species of the eleotrid cavefish genus Typhleotris was described from an isolated karst sinkhole called Grotte de Vitane in coastal southwestern Madagascar. Its specific name is derived from the Malagasy words marary (“ill or sick”) and be (“big”), meaning “very sick” or “big sickness.” The name commemorates the strange and debilitating viral fever that members of the field team suffered after diving in the sinkhole.

As far as we know, the etiology of the “sinkhole fever” has not been explained.

2 July 2014

Austroglanis Skelton, Risch & de Vos 1984

Austroglanis, known as Rock Catfishes, belongs to a small family, Austroglanididae, of just

three (exceedingly rare) species from South Africa and Namibia. The generic name is derived from auster (south wind) and glanis (an ancient word for catfish), and refers to its being the most southernly distributed catfishes in Africa. The generic name is not what intrigues us, though. Instead, we’d like to call your attention to a charming tradition that’s being followed in the specific names of all three species.

Boulenger described the first known species, Gephyroglanis (now Austroglanis) sclateri, in 1901. He named it in honor of William Lutley Sclater (1863-1944), the Director of the South African Museum, who supplied the type.

Barnard described a second species, Gephyroglanis (now Austroglanis) gilli, in 1943. He named it in honor of Edwin Leonard Gill (1877-1956), who succeeded Sclater as Director of South African Museum. Barnard noted that it was “appropriate” to name this species, as Boulenger had 42 years earlier, after the current Director of the South African Museum.

In 1981, Skelton continued the tradition, naming a third species, Gephyroglanis (now Austroglanis) barnardi, in honor of Keppel Harcourt Barnard (1887-1964), who described A. gilli in 1943. Barnard succeeded Gill as Director of the South African Museum in 1946.

We don’t know who succeeded Barnard. If a new species of Austroglanis is discovered, will its author(s) continue the tradition?

25 June 2014

25 June 2014

Ameiurus natalis (Lesueur 1819)

UPDATE: See “Name of the Week” for 7 August 2019 for a new explanation regarding this name. Like many of his contemporaries, David Starr Jordan (1851-1931) was schooled in classical Latin. But when it came to explaining the specific epithet of the Yellow Bullhead Catfish, Ameiurus natalis (Lesueur 1819), the dean of American ichthyology got it wrong. He not only mistranslated the Latin word natalis, he also overlooked an easy-to-see two-word phrase in the original description that clearly indicated Lesueur’s intention with the name. As a result, every “Fishes of …” book and online reference that includes a section on the etymology of Ameiurus natalis has repeated Jordan’s mistake.

The word natalis does not mean “having large nates, or buttocks,” per Jordan (that would be the Latin word natis). Nor does the name allude to any characters mentioned in Lesueur’s description, nor to a host of other characters — an enlarged adipose fin, a swollen and elevated caudal peduncle, the anal fin, the swollen nape of breeding males, the catfish’s overall chubby appearance — proffered by ichthyologists over the years in their attempts to explain the “buttocks” allusion.

The true meaning of natalis is far, far different from buttocks. It means “day of birth” in classical Latin and refers to the birth of Christ, or Christmas, in Church Latin. (Several animals endemic to Christmas Island, including two fishes and the famous crab, are named natalis.) The reason why Lesueur selected this name is unclear, but his intentions are not: Immediately preceding the introduction of the Latin binomial Pimelodus natalis, Lesueur provided a French vernacular version of the name, typeset in a conspicuous small-cap font: PIMELODE NOËL.

Since Lesueur named other fishes in the same publication based on their color, we can hazard to guess that his selection of natalis (and Noël) refers to the red and greenish (olive) tint on the fins of the catfish he examined (no types survive, by the way). Were red and green associated with Christmas in 1819? According to our research, the answer is yes. In fact, those colors, evoking the color of berries on holy sprigs, dates to at least the Middle Ages.

We’ll likely never know why Lesueur named a plump North American bottom-dweller after Christmas. (Did he catch his on December 25?) But we do know that the name has nothing to do with the rear pelvic area of the human body.

18 June 2014

Homalopteroides avii Randall & Page 2014

The original description of this new species of hillstream loach (Balitoridae) from the Rajang River basin, Sarawak, has one of the most beautiful and heartfelt name etymologies we’ve ever read:

“Named avii, in memory of Lawrence ‘Avi’ Greenberg (21 July 1982–26 November 2011). The diagnostic lateral cephalic stripe of this species, reminiscent of a smile, is a symbol of Avi’s gentle disposition and goodhearted nature. He is an inspiration to and missed friend of the first author and many others.”

Iguanodectes dentition. From: Cope, E. D. 1872. On the fishes of the Ambyiacu River. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia v. 23: 250-294, Pls. 3-16.

11 June 2014

Cope headscratcher #4: Iguanodectes

Any herpetologists who can help with this one?

In 1872, Edward Drinker Cope proposed another of his etymologically enigmatic names: Iguanodectes, a genus of South American tetras (Iguanodectidae) with currently eight valid species. Iguana, we’re pretty sure, means lizard; dectes means teeth. Does this mean that these tetras — or at least the type species, I. tenuis (actually a junior synonym of I. spilurus [Günther 1864]) — have lizard-like teeth? Cope’s brief description offers no clue as far as we can tell:

Teeth of the outer row very few, minute. …

This genus is allied to Tetragonopterus, but the dentition is much weaker, approaching that of the Schizodon … In the only species there are but two minute teeth of the outer premaxillary row. The other teeth are fan-shaped and smooth, and in contact, so as to form an uninterrupted series. In Tetragonopterus the fangs are strong, not contracted, and the crowns are ridged.

Does this in any way describe a lizard’s teeth? Or an iguana’s teeth? (The accompanying illustration is from Cope’s original description.) In addition to being an ichthyologist, Cope was also a herpetologist. So he probably chose the iguana epithet for good reason.

If you know, or have an educated guess, please let us know. Thanks.

4 June 2014

Puntigrus Kottelat 2013

Puntigrus is the new genus name for five distinctively colored cyprinids of Southeast Asia, including the aquarium favorite, the Tiger Barb (P. tetrazona). The name is a combination of Puntius (former genus in which all species had been assigned) and tigrus, Latin for tiger, referring to the blackish bands that encircle the bodies of all included species.

This new genus was described by Swiss ichthyologist Maurice Kottelat in a sweeping taxonomic overhaul of Southeast Asian inland fishes that appeared in late 2013. How sweeping? Consider this: Within the family Cyprinidae alone, Kottelat has proposed ~270 taxonomic and nomenclatural changes. These include (by our count):

- 113 generic reassignments

- 49 taxa resurrected from synonymy

- 37 taxa subsumed into synonymy

- 31 date-of-publication corrections

- 13 gender-agreement corrections

- 9 spelling corrections (name or author)

- 4 new genera

And more.

We are highlighting the name Puntigrus this week to bring attention to the fact that we have just completed a major overhaul of our Cyprinidae pages based on most (but not all) of Kottelat’s proposed changes. (We retained a handful of taxa that Kottelat tentatively placed in synonymy, and we disagreed with a few gender-agreement corrections based on our interpretation whether a name was an adjective or a noun.)

We’ve also amended pages for other fish groups based on Kottelat’s recommendations, but Cyprinidae — with 832 species in Southeast Asia — was the big revision that took us months to complete.

Of course, Kottelat’s study is not the last word in Southeast Asian fish taxonomy. According to the author, ~300 new species are sitting on museum shelves awaiting description and that a “fair number” of synonyms await re-validation. In addition, Kottelat predicts that an additional 500 species still await discovery in the wild.

Looks like updating The ETYFish Project will keep us plenty busy for a long, long time!

Illustration by Charles Lesueur. From: Gilliams, J. 1824. Description of a new species of fish of the Linnean genus Perca. Journal of the Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia v. 4 (pt 1): 80-82, Pl. 3.

28 May 2014

Aphredoderus sayanus (Gilliams 1824)

The species that got one of us (CS) interested in fish-name etymology is the peculiar North American endemic Aphredoderus sayanus, commonly known as the Pirate Perch.

What’s peculiar about this fish is the anterior placement of its anus, just under the head, in front of the pelvic fins. This led Lesueur (1833) to coin the name Aphredoderus for its genus, a combination of aphodos (Greek for excrement) and dere (Greek for neck or throat).

The species itself was described by Philadelphia dentist-naturalist Jacob Gilliams a few years earlier in 1824. He named it Scolopsis sayanus, believing it was related to Scolopsis Cuvier 1814 (now confined to threadfin breams of the Indian Ocean and western Pacific) due to its “spinous suborbital.” [Note: Curiously, the title of Gilliam’s paper places the species in the genus Perca.]

It’s the specific epithet sayanus that we found so intriguing. While Gilliams did not specifiy such in his brief description, he named the fish after his good friend and colleague, naturalist Thomas Say (1787-1834). We wondered if the “-anus” part of the name referred to the fish’s anatomical curiosity. We also wondered if, by combining “say” with “anus,” Gilliams was having some fun at his friend’s expense. Or maybe they weren’t friends at all, but rivals or enemies, and Gilliams was exacting some comeuppance or revenge by immortalizing Say in a epithet that basically called him an ass. (There is some precedent for this; Linnaeus famously named some noxious weeds after people he disliked.)

Alas, none of our speculation panned out. “-anus” is a suffix that means “belonging to” and is commonly used in tributes and honoraria. (Had the genus been feminine, the species name would have been sayana). Beyond that, the fish’s peculiar anus was unknown to Gilliams; it was first reported by Lesueur when he proposed the genus in 1833.

Nevertheless, we enjoyed researching the name. We then became curious about other fish names. Twenty-three years later, The ETYFish Project was born!

21 May 2014

Tahuantinsuyoa macantzatza Kullander 1986

Many scientific names are hard to pronounce, but in the world of fishes, no name twists our tongue harder than this one. Swedish ichthyologist Sven O. Kullander coined both the generic and specific names in his 1986 monograph, Cichlid fishes of the Amazon River drainage of Peru, and he must have smiled knowing how hard it would be for cichlid enthusiasts to pronounce this fish’s name let alone spell it!

The generic name is from the Quecha name for the Inca Empire, Tahuantinsuyo. (Quecha is the name of a people of the central Andes of South America and their languages.) The specific name is a combination of the Shipibo words for stone (macan) and fish (tzatza), referring to the predominantly stony bed of the Río Huacamayo, this cichlid’s type locality in Peru. (Shipibo is a language spoken by indigenous people along the Ucayali River in the Amazon rainforest in Peru.)

For the record, according to Dr. Kullander’s web site, an acceptable pronunciation of the generic name (in English) is:

Tah-wanteen-soo-you-ah

What fish name do you find particularly hard to pronounce?

![couch-1867-antique-fish-print.-remora-25003-p[ekm]416x312[ekm]](https://etyfish.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/couch-1867-antique-fish-print.-remora-25003-pekm416x312ekm-300x225.jpg)

Antique woodblock from A History of the fishes of the British Islands, 1st edition, by Jonathan Couch (1862-1867), Groombridge & Sons, London. Printed in color and finished by hand.

14 May 2014

Remora remora (Linnaeus 1758)

Some names go way back. Remora, for example, the familiar genus of “sharksuckers” that hitch rides on the bodies of sharks and whales and the hulls of boats, dates from classical antiquity. “Remora” is Latin for “delay” or “hindrance.” The name was applied to these fishes because ancient mariners believed the fish could actually slow or stop a ship from sailing.

Echeneis, another genus of remoras, is also named for its mythical boat-stopping properties. The name comes from Greek echein (“to hold”) and naus (“a ship”).

Pliny the Elder (ca. AD 24 to AD 79), in Book 32, Vol. 6 of his “Natural History” (ca. AD 77-79), blames the defeat of Mark Antony at the Battle of Actium (a naval engagement fought between the forces of Octavian and the combined forces of Mark Antony and Cleopatra VII) on the remoras (or echeneis) that had attached themselves to Mark Antony’s ships:

At the battle of Actium, it is said, a fish of this kind stopped the praetorian ship of Antonius in its course, at the moment that he was hastening from ship to ship to encourage and exhort his men, and so compelled him to leave it and go on board another. Hence it was, that the fleet of Caesar gained the advantage in the onset, and charged with a redoubled impetuosity.

This defeat, according to historians, indirectly led to the death of Caligula.

Pliny gave a second example of the remora’s alleged impact on history:

In our own time, too, one of these fish arrested the ship of the Emperor Caius in its course, when he was returning from Astura to Antium: and thus, as the result proved, did an insignificant fish give presage of great events; for no sooner had the emperor returned to Rome than he was pierced by the weapons of his own soldiers. Nor did this sudden stoppage of the ship long remain a mystery, the cause being perceived upon finding that, out of the whole fleet, the emperor’s five-banked galley was the only one that was making no way. The moment this was discovered, some of the sailors plunged into the sea, and, on making search about the ship’s sides, they found an echeneis adhering to the rudder. Upon its being shown to the emperor, he strongly expressed his indignation that such an obstacle as this should have impeded his progress, and have rendered powerless the hearty endeavours of some four hundred men. One thing, too, it is well known, more particularly surprised him, how it was possible that the fish, while adhering to the ship, should arrest its progress, and yet should have no such power when brought on board.

Clearly, a foot-long fish cannot stop or hinder a 120-foot-long ship. So what might explain this curious bit of unnatural natural history? The Greek historian Plutarch (ca. AD 46 to AD 120), in a collection of essays called Moralia, observed that ships with clean hulls “cut the waves” faster than ships whose hulls and keels are overgrown with “mosse” and “kilpe” (i.e., kelp, or seaweed). Plutarch also observed that remoras “willingly cleaveth” to “matter soft and tender.” Not recognizing the relationship between the remoras and seaweed, the ancients blamed the former.

The fact that remoras form a vacuum seal and are difficult to manually remove probably added to their mythical status as well.

Photograph of live paratype from Hubbs, C. L. and W. T. Innes. 1936. The first known blind fish of the family Characidae: a new genus from Mexico. Occasional Papers of the Museum of Zoology University of Michigan No. 342: 1-7, Pl. 1.

7 May 2014

Astyanax jordani (Hubbs & Innes 1936)

No one has been honored in more fish names than the dean of American ichthyology of David Starr Jordan. We count at least 65 times — Davidijordania jordaniana, anyone? — including names now in synonymy.

This name, however, isn’t one of them.

The famous Blind Cave Tetra of México — originally Anoptichthys jordani — is actually named after C. Basil Jordan, Texas Aquaria Fish Company (Dallas, Texas, USA), for the “gift” of the type specimens and for the “privilege of making his interesting discovery [the first-recorded blind characin] known to the scientific and aquarium world.”

(Some backstory: Jordan, an aquarium-fish dealer, heard rumors of blind fish in Mexico and commissioned local Indians to collect any fish from caves at San Luis Potosí. After wading in one cave for a kilometer or so, the men discovered a huge cave filled with stalagmites, stalactites, and deep water containing the Blind Cave Tetra. Jordan received 75 specimens, which he successfully bred in his aquaria.)

We’re okay with naming this species after the person who brought it to the attention of science. But considering how many fishes have been named jordani already — and perhaps knowing that people would normally associate this name with the other, more-famous Jordan (who Hubbs studied under, by the way) — wouldn’t Hubbs and Innes have done a better job honoring the less-famous Jordan if they had named this species “basiljordani” instead? Just sayin’.

30 April 2014

Cope headscratcher #3: Triportheus

Triportheus trifurcatus. From: Castelnau, F. L. 1855. Poissons. In: Animaux nouveaux or rares recueillis pendant l’expédition dans les parties centrales de l’Amérique du Sud, de Rio de Janeiro a Lima, et de Lima au Para; exécutée par ordre du gouvernement Français pendant les années 1843 a 1847. Part 7, Zoologie. Paris (P. Bertrand). v. 2: i-xii + 1-112, Pls. 1-50.

Here is the third in a series of enigmatic names coined by American ichthyologist-herpetologist-paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope, the one taxonomist who confounds us more than any other. But unlike previous entries in the series, we believe we have the meaning of this name figured out.

In 1872, Cope created the characiform genus Triportheus, now comprising 16 species throughout most of the major river drainages of South America. Species in the genus easily recognized by their expanded, keeled coracoids and large pectoral fins. But it seems Cope had their dentition in mind when he coined the name.

Tri-, of course, means three. No mystery there. Portheus is more enigmatic. It translates as “ravager or destroyer.” Our guess is that Cope is following the tradition of coining colorful, evocative names for characiform genera that somehow describe the sharpness and/or trophic function of their teeth. For example:

Charax Scopoli 1777 — from Greek word meaning “palisade of pointed sticks,” referring to densely packed sharp teeth

Alestes Müller & Troschel 1844 Greek for miller or grinder, presumably referring to inner row of premaxillary molariform teeth

Brycon Müller & Troschel 1844 — from bryco, to bite, gnash teeth or eat greedily, presumably referring to their fully toothed maxillae

Phago Günther 1865 — eating or devouring, presumably referring to mouth “armed with a series of strongish, compressed, tricuspid teeth round its entire margin”

One way we determine or confirm the meaning of a name when it’s not clear from the original description is to see if the same author used it for a different taxon in another description. Sure enough, Cope had. The year before, Cope described Portheus, a fossil fish genus from Kansas, USA. In his description he noted its “uncommonly powerful offensive dentition.”

So, feeling confident that Cope was referring to teeth with the “portheus” half of the name, we then had to find an attribute in his text that could pay off his selection of tri-, or three. Cope mentioned that the genus has three series of teeth on the premaxillary, in contrast to the morphologically similar Chalcinus (now = Triportheus), which has two series of teeth on the premaxillary teeth, and Chalcinopsis (now = Brycon), which has four.

And there you have it: Triportheus Cope 1871 is named for its three series of premaxillary teeth. Whether the teeth of these surface-feeding insectivorous fishes warrant “ravager” or “destroyer” status is entirely up to you.

23 April 2014

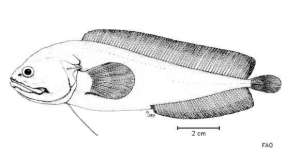

Neoharriotta quraishii Ali-Khan & Hussain 1999

What if you published a new species description in 1999 and no one knew about it? It didn’t show up in any zoological abstracts or indices. You googled the name and nothing came up. You checked Eschmeyer’s comprehensive Catalog of Fishes — not there, either. Well, that’s kind of what happened with this description:

Ali-Khan, J., and S. M. Hussain. 1999. Neoharriotta quraishii — a new species of Rhinochimaeridae from the Western Arabian Sea. Pakistan Journal of Marine Biology 5 (1): 93-97.

We didn’t know about this paper – no one knew about it, it seems – until one of the authors forwarded a copy to Bill Eschmeyer this past weekend. We suspect that the new species, based on one specimen, may be a junior synonym of Neoharriotta pumila, described by Didier & Stehmann in 1996. [Update 8 Jan. 2017: It is.] Both species come from the same area and the authors of the latter were unaware of the former.

But if and when the species is formally synonymized, we’re happy to rescue the name from the obscurity it has languished in for nearly 15 years.

The specific epithet, quraishii, is in honor of the late M. R. Quraishi, founder and first Director of the Central Marine Fisheries Department, Government of Pakistan, for his “life long interest, efforts, devotions and contributions in the fields of ichthyology, fisheries and taxonomy of fish.”

The generic name, Neoharriotta, was coined by Bigelow & Schroeder in 1950 when they established a new genus for the species Harriotta pinnata. It means just that: a new genus of Harriotta.

Harriotta, by the way, proposed by Goode & Bean in 1895, honors Thomas Harriott (ca. 1560-1621), an English astronomer, mathematician, ethnographer and translator who published the first English work on American natural history in 1588.

It’s interesting to see the names of a 16th-century English polymath and a late-20th-century Pakistani fisheries scientist honored in the same binomen.

16 April 2014

Petrocephalus boboto Lavoué & Sullivan 2014

War in the Democratic Republic of the Congo has killed more than 5.4 million people since 1998. Rapes and sexual violence in the country represent a growing epidemic. Despite the formation of a transitional government in 2003, people in the east of the country remain in terror of marauding militias and the army.

Against this violent backdrop, the name of a new species of mormyrid, or elephantfish, offers a message of hope: Petrocepehalus boboto.

“Boboto” is a word in Lingala, the language spoken at the type locality of the new species (Congo River at Yangambi, Orientale Province, D.R. Congo). It means “peace.”

“We named this hard-to-find Petrocephalus species ‘boboto’ in the hopes that solutions for peace — though elusive like this fish — can be found in eastern D.R. Congo and the other troubled areas of Central Africa,” said John P. Sullivan, who, along with Sébastien Lavoué, described the new species.

Lavoué and Sullivan described another new species in the same publication. Petrocephalus arnegardi is named for colleague and friend Matthew E. Arnegard, for contributions to the study of mormyrid evolution and diversification; in addition, Arnegard is a member of the “Mintotom Team” of researchers associated with the Carl D. Hopkins Laboratory (Cornell University), who have conducted field studies on African weakly electric fishes for more than 15 years. (Mintotom is the plural form of the word for mormyrid fish in the Fang language of West Central Africa.)

You can read or download Lavoué and Sullivan’s paper here:

By the way, Petrocephalus, coined by Marcusen in 1854, is formed by the Latin petro (stone) and cephalus (head). It is a Latin translation of the Arabic vernacular ras el hagar (“stonehead”), which may refer to the species’ short, well-rounded (i.e., stone-like) snout.

9 April 2014

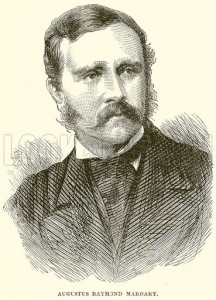

Poropuntius margarianus (Anderson 1879)

Last week’s selection of Rita sacerdotum, named by Scottish zoologist John Anderson in 1879, reminded us of another interesting name from the same publication.

Barbus (now placed in Poropuntius) margarianus is a small minnow found in Yunnan, China, and Myanmar. It was named after, to use Anderson’s word, the “lamented” British diplomat and explorer, Augustus Raymond Margary (1846-1875). Why lamented? Because Margary — as well as his entire staff — were murdered on 21 February 1875 while surveying overland trade routes between Burma and Yunnan, China. His murder and the diplomatic crisis it caused between England and China, was called “The Margary Affair.”

British authorities used Margary’s murder to pressure the Qing government on a number of unrelated issues. The crisis was resolved in 1876 when both countries signed the Chefoo Convention, which covered a number of diplomatic/political items. The British demanded, and got, an indemnity of 700,000 taels of silver, an apology to Queen Victoria, and access to four more ports for trade.

Margary, write Anderson, was “thoroughly versed in the Chinese language and etiquette.” He “took a lively interest in the scientific objects of the [Yunnan] Expedition of 1875, but was ruthlessly murdered by the Chinese at Manwyne.”

2 April 2014

2 April 2014

Rita sacerdotum Anderson 1879

This catfish from the Irrawaddy basin of Myanmar was described by Scottish zoologist John Anderson (1833-1900) in a two-volume work called “Anatomical and zoological researches: comprising an account of the zoological results of the two expeditions to western Yunnan in 1868 and 1875.”

The generic name Rita is a local Bengalese name for related catfish species in India. The specific name sacerdotum means “priests.” Anderson explains why: