NAMES OF THE WEEK from: 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 2024 2025

27 December

Gender “uncorrections”

I admit I was wrong about this one. Many of us were. But our intentions were correct. Grammatically correct.

According to Article 31.1.2 of the ICZN Code: “A species-group name, if a noun in the genitive case formed directly from a modern personal name, is to be formed by adding to the stem of that name –i if the personal name is that of a man, –orum if of men or of man (men) and woman (women) together, –ae if of a woman, and –arum if of women; the stem of such a name is determined by the action of the original author when forming the genitive.”

An example of each:

Scorpaenodes smithi Eschmeyer & Rama-Rao 1972 – named after South African ichthyologist J. L. B. Smith (1897–1968)

Canthigaster smithae Allen & Randall 1977 – named after Smith’s wife, Margaret Mary Smith (1916–1987), a fish illustrator and first director of the J. L. B. Smith Institute of Ichthyology (now the South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity)

Pempheris smithorum Randall & Victor 2015 – named after both J. L. B. and Margaret Smith

Didogobius janetarum Schliewen, Wirtz & Kovačić 2018 – named after Janet Van Sickle Eyre (b. 1955), Reef Environmental Education Foundation, and philanthropist Janet Van Sickle Eyre, who supported the authors’ goby research

Unfortunately, some taxonomists do not follow Article 31.1.2, either through ignorance, carelessness or choice.

Myself, the editors of Eschmeyer’s Catalog of Fishes (ECoF), and some taxonomists working with bird and herp names, strictly interpreted four words in Article 31.1.2 — “is to be formed” — to mean “must be formed.” So, we began “correcting” the spellings of species-group names that did not agree with the gender of the people being honored.

In addition to believing such cases were mandated by the Code, we thought it was just good grammar. Affixing a masculine suffix to a woman’s name is like addressing her as “Mister.” It just sounds stupid! Also, when I see an eponym with the “-i” case ending and do not know the identity of the dedicatee, I automatically suspect that it’s named after a man. This may reflect my own male bias, but it also reflects the fact that men have dominated science and taxonomy until more recent times. If Allen & Randall had named the Bicolored Toby, a pufferfish from South Africa, “Canthigaster smithi,” I would have suspected they had honored the famous South African ichthyologist J. L. B. Smith. But since they named it C. smithae, I have reason to believe they honored Smith’s wife and scientific partner Margaret Mary Smith, an ichthyologist herself. A correctly used genitive ending helps to convey accurate information about the name.

As ECoF “corrected” spellings in their database and I in mine, we occasionally received notes from ichthyologists saying that our “corrected” spellings were wrong, that ICZN Code did not mandate nor even allow the changes we were making. They also pointed out that our new spellings threatened nomenclatural stability. We countered by quoting the “is to be formed” wording of Article 31.1.2, and that the spellings of adjectival specific-group names are emended all the time when the species is moved from, say, a masculine genus to a feminine genus. If changing “maculatus” to “maculata” does not upset nomenclatural stability, then what’s the problem with changing “larsoni” to “larsonae” (named for goby expert Helen Larson)?

We stubbornly pushed on, but the issue was like a stone in my shoe. Then one day, while reading the ICZN Code on line, I saw that the ICZN had posted a FAQ page, which features the question: “If I find a name is incorrectly spelled, what do I do?” The answer:

“If the ending of a species name which is an adjective does not agree with the gender of the genus then it has to be corrected. However names based on personal names with incorrectly Latinized endings are not corrected as this would cause instability (Article 32.5.1, glossary definition of Latinization). I.e. a species which was named smithi after a woman with the surname smith is not incorrectly spelled even though the normal feminine Latinization is smithae.”

According to Article 32.5.1: “If there is in the original publication itself, without recourse to any external source of information, clear evidence of an inadvertent error, such as a lapsus calami or a copyist’s or printer’s error, it must be corrected. Incorrect transliteration or latinization, or use of an inappropriate connecting vowel, are not to be considered inadvertent errors.”

In short, honoring a woman named Smith with the eponym “smithi” is not an incorrect spelling. It’s simply an incorrect latinization. So, while Article 31.1.2 says the “smithae” spelling “is to be,” Article 32.5.1 acknowledges the error but gives it a pass. Sticklers for Latin grammar may wince at the name, but they cannot correct it. Our attempts to correct it are termed “unjustified emendations.”

I alerted the ECoF editors of the ICZN rule and they “uncorrected” all the names they (with my help) had unjustifiably emended over the past few years. I “uncorrected” them at ETYFish as well. With the grammatically correct but incorrectly emended spelling listed first, and the grammatically incorrect but correct original spelling listed first, these names are:

Dipturus grahamorum > grahami Last 2008 – named for two ichthyologists named Graham

Scolecenchelys nicholsarum > nicholsae (Waite 1904) — named for a woman and her daughters

Ilisha sirishae > sirishai Seshagiri Rao 1975 — named for the daughter of the author’s cousin

Mesonoemacheilus remadeviae > remadevii Shaji 2002 — in honor of Karunakaran Rema Devi, Zoological Survey of India, a woman

Paracobitis abrishamchianum > abrishamchiani Mousavi-Sabet, Vatandoust, Geiger & Freyhof – named for a father and son

Paraschistura susianorum > susiani Freyhof, Sayyadzadeh, Esmaeili & Geiger 2015 – in honor of the Susian people of 4200 BC

Schistura rosammae > rosammai (Sen 2009) – in honor of Rosamma Mathew, Zoological Survey of India, a woman

Labeobarbus bynni waldronae > waldroni (Norman 1935) – in honor of Fanny Waldron, a collector for the British Museum, a woman

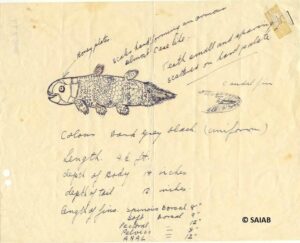

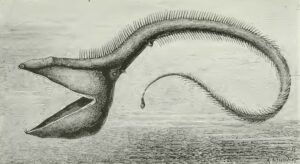

Tor remadeviii. From: Kurup, B. M. and K. V. Radhakrishnan. 2011. Tor remadevii, a new species of Tor (Gray) from Chinnar Wildlife Sanctuary, Pambar River, Kerala, southern India. Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society 107 (3): 227‒230. [Publication dated Sept.-Dec. 2010 but published Oct. 2011.]

Tor remadeviae > remadevii Madhusoodana Kurup & Radhakrishnan 2011 – in honor of Karunakaran Rema Devi, Zoological Survey of India, a woman

Sinibrama melroseae > melrosei (Nichols & Pope 1927) – in honor of Mrs. J. C. Melrose, a missionary in China

Poecilocharax bovaliorum > bovalii Eigenmann 1909 – named for two men named Bovalius, presumably relatives

Hyphessobrycon peugeotorum > peugeoti Ingenito, Lima & Buckup 2013 – named for the Peugeot family (best known for their cars)

Bryconacidnuse ellisae > ellisi (Pearson 1924) — named for Marion Durbin Ellis, a woman

Hemibrycon gutierrezorum > gutierrezi Ardila Rodríguez 2020 – named for the philanthropic Gútierrez Gómez family

Pseudohemiodon almendarizae > almendarizi Provenzano-Rizzi, Argüello & Barriga-Salazar 2022 – in honor of Ana de Lourdes Almendáriz, a female herpetologist

Galeichthys troworum > trowi Kulongowski 2010 – named for a father and son

Neoarius midgleyorum > midgleyi (Kailola & Pierce 1988) – named for a husband and wife

Chasmocranus lopezae > lopezi Miranda Ribeiro 1968 – named for the woman who collected holotype

Gymnorhamphichthys bogardusae > bogardusi Lundberg 2005 – in honor of Joan Bogardus Spears (1939–2002), whose daughter supported Lundberg’s work

Notolepis coatsorum > coatsi Dollo 1908 – named for brothers who helped finance the Scottish National Antarctic Expedition

Sciadonus robinsorum > robinsi Nielsen 2018 – named for father-and-son ichthyologists

Callogobius clarkae > clarki (Goren 1978) – named for ichthyologist Eugenie Clark (1922–2015), a woman

Pictichromis paccagnellorum > paccagnellae (Axelrod 1973) – named for the Paccagnella family, Bologna, Italy, aquarium fish wholesalers who provided holotype

Lissonanchus lusherae > lusheri Smith 1966 – named for Mrs. D. N. Lusher, who collected holotype

Aphyosemion lambertorum > lambertori Radda & Huber 1977 – named for two killifish experts both named Lambert

Austrolebias vandenbergorum > vandenbergi (Huber 1995) – named for father-and-son aquarists

Fundulus herminiamatildarum > herminiamatildae García-Ramírez, Lozano-Vilano & De la Maza Benignos 2022 – named for two the first authors’ parents, Herminia Ramírez and Matilde García

Monolene mertensae > mertensi (Poll 1959) – in honor of Mrs. P. Mertens, who illustrated many of Poll’s publications

Acanthopagrus morrisonae > morrisoni Iwatsuki 2013 – in honor of Sue M. Morrison, who collected type specimens and tissue samples

Pseudanthias engelhardi. Photo by Roger C. Steene. From: Allen, G. R. and W. A. Starck II. 1982. The anthiid fishes of the Great Barrier Reef, Australia, with the description of a new species. Revue française d’Aquariologie Herpétologie 9 (2): 47–56.

Bembrops greyae > greyi Poll 1959 – named for Marion Grey (1911–1964), Chicago Natural History Museum, a woman

Pseudanthias engelhardorum > engelhardi (Allen & Starck 1982) – named for philanthropist Charles W. Englehard, Jr. (1917–1971) and his family

Lepidotrigla larsonae > larsoni del Cerro & Lloris 1997 – in honor of goby expert Helen Larson

Paraliparis freebornae > freeborni Stein 2012 – in honor of scientific illustrator Michelle Freeborn

For several eponyms, the ECoF editors opted to retain the emended spellings because they, in their assessment, are in “prevailing usage.” According to Article 33.2.3.1, “when an unjustified emendation is in prevailing usage and is attributed to the original author and date it is deemed to be a justified emendation.” In other words, if I change the grammatical spelling of an eponym, which Article 32.5.1 says I cannot do, but other taxonomists start using my spelling, then, per Article 33.2.3.1, my emended spelling is okay.

According to ECoF, these species-group names meet the “prevailing usage” criteria:

Myxine robinsorum Wisner & McMillan 1995 – originally spelled robinsi, named for both C. Richard Robins and his wife Catherine

Squaliolus aliae Teng 1959 – originally spelled alii, in honor of the author’s wife

Cobitis battalgilae Bacescu 1962 – originally spelled battalgili, in honor of Turkish ichthyologist Fahire Battalgil (later Battalgazi) (1905–1948), a woman

Pangio mariarum (Inger & Chin 1962) – originally spelled mariae, in honor of the authors’ wives, both named Maria

Oxynoemacheilus veyselorum Çiçek, Eagderi & Sungur 2018 – originally spelled veyseli, named for father and son of first author, both named Veysel

Physoschistura raoi (Hora 1929) – originally spelled raoe, named for H. Srinivasa Rao (1894–1971), Zoological Survey of India, a man

Notropis cummingsae Myers 1925 – originally spelled cummingsi, in honor of Mrs. J. H. Cummings (1885–?), an amateur naturalist

Tewara cranwellae. From: Griffin, L. T. 1933. Descriptions of New Zealand fishes. Transactions of the New Zealand Institute 63: 171–177, Pls. 24–25. Illustration by the author.

Panaque suttonorum Schultz 1944 – originally spelled suttoni, named for Dr. and Mrs. Fredrick A. Sutton, who helped Schultz in Venezuela

Callopanchax sidibeorum Sonnenberg & Busch 2010 – originally spelled sidibei, named for Samba Sidibe and his family, who first collected this species

Tewara cranwellae Griffin 1933 – originally spelled cranwelli, named for botanist Lucy Cranwell (1907-2000), a woman

If anything, this exercise demonstrates the seemingly contradictory objectives of ICZN Articles 31.1.2, 32.5.1 and 33.2.3.1.

20 December

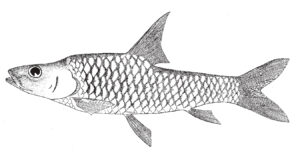

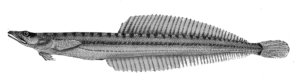

Semotilus atromaculatus (Mitchill 1818)

I have an unbreakable rule when it comes to researching the etymologies of fish names: Do not rely on secondary sources, such as regional “Fishes of …” books, no matter how good they are. Instead, always begin with the original publication in which the name was proposed. I apparently broke this rule with the specific epithet of the Creek Chub Semotilus atromaculatus, a common minnow of the eastern United States and Canada.

Physician-politician-naturalist Samuel L. Mitchill (1764–1831) described the species as Cyprinus atromaculatus in 1818. The specific name means “black spotted.” Some references, including ETYFish, tell you that the black spot in question is the black spot at the anterior edge of the dorsal-fin base. This explanation is given in two major books: Freshwater Fishes of Virginia (Jenkins & Burkhead, 1994) and Fishes of Alabama (Boschung & Mayden, 2004). Indeed, the dorsal-fin spot is a major diagnostic character of the species.

The trouble is, Mitchill never mentioned this dorsal spot in his brief description. Instead, he mentioned that the fish’s back, sides, belly and fins are “marked by black dots, consisting of a soft or viscous matter, capable of being detached by the point of a knife without lacerating the skin …”.

I learned of this discrepancy while reading Hornyheads, Madtoms, and Darters: Narratives on Central Appalachian Fishes, a new (October 2023) book by Stuart A. Welsh, Adjunct Professor of Ichthyology in the Wildlife and Fisheries Resources program at West Virginia University. This excellent and highly readable book is a collection of 23 essays on the fishes of central Appalachia, with an emphasis on ecology and the contributions of “old school” naturalists such as Mitchill. In the chapter titled “Spots and Dots,” Welsh posits that the “black dots” of Mitchill’s specimen are external black cysts that contain a parasitic flatworm called a trematode. This condition is often called Black Spot Disease. I have collected many Creek Chub (a common fish where I live) and several other species covered with these unsightly black spots.

I learned of this discrepancy while reading Hornyheads, Madtoms, and Darters: Narratives on Central Appalachian Fishes, a new (October 2023) book by Stuart A. Welsh, Adjunct Professor of Ichthyology in the Wildlife and Fisheries Resources program at West Virginia University. This excellent and highly readable book is a collection of 23 essays on the fishes of central Appalachia, with an emphasis on ecology and the contributions of “old school” naturalists such as Mitchill. In the chapter titled “Spots and Dots,” Welsh posits that the “black dots” of Mitchill’s specimen are external black cysts that contain a parasitic flatworm called a trematode. This condition is often called Black Spot Disease. I have collected many Creek Chub (a common fish where I live) and several other species covered with these unsightly black spots.

Black Spot Disease is caused by digenean trematodes (flukes) of the families Diplostomatidae and Heterophyidae. The raised black “spots” (actually nodules) are where the parasite has encysted itself in the skin of the fish. The fish serves as a second intermediate host for the trematode. They acquire the parasite from infected snails, the first intermediate host. When fish-eating birds and mammals eat the infected fish, trematode eggs within the feces are released into the water. When the eggs hatch, they parasitize the snails. Then the larvae transform into a free-swimming form, whereupon they infect fish. The cycle then continues.

Semotilus atromaculatus with Black Spot Disease (genus Neascus), Fletcher’s Creek, Ontario, Canada. Photo by Noah Poropat. Source: Wikipedia.

I have not conducted an exhaustive literature search, but I believe Dr. Welsh is the first person to offer the trematode explanation for “atromaculatus.” It clearly makes sense, especially since Mitchill described the black dots as “soft or viscous matter, capable of being detached by the point of a knife without lacerating the skin …”. The ETYFish entry has been revised.

Dr. Welsh mentions the etymology of the generic name Semotilus: sema means banner (i.e., dorsal fin), and telia means spotted, referring to the black dorsal-fin spot that myself and others believed was referenced in the specific name atromaculatus. Most other “Fishes of …” books present a similar explanation. It’s probably correct, but etymologically it doesn’t make sense. The name was proposed by the eccentric naturalist Constantine Samuel Rafinesque in 1820. One of his eccentricities was a rather creative (some would say careless) command of Latin and Greek. At times he seems to have possessed a Latin or Greek dictionary consisting of words of his own spelling or invention. Semo– is probably derived from sēmeī́on (Gr. σημεῖον), meaning banner or dorsal fin. But the second half of the name, does not track with any known Greek word. In 1878, David Starr Jordan, who often criticized Rafinesque’s nomenclatural “monstrosities,” simply presumed that Rafinesque believed it to mean “spotted.” This explanation has survived to the present.

According to Holger Funk, our resident Greek and Latin scholar, tilus sounds like a Latinization of τίλος (tílos), plucked, which obviously doesn’t make any sense here. Another Greek word vaguely reminiscent of “tilus” is téleios (τέλειος) which, however, does not mean “spotted.” In fact, it means the opposite — “perfect” or “without spot or blemish.” Another possibility is that –tilus is nothing more than a suffix with no specific meaning on its own, only used in combination with a preceding word component.

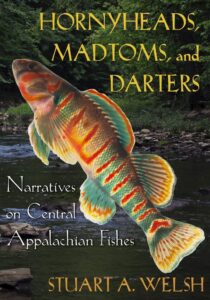

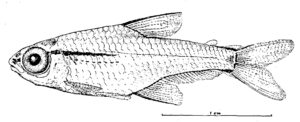

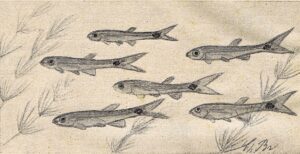

Cyanogaster noctivaga, paratype, photographed right after capture at night. From: Mattox, G. M. T., R. Britz, M. Toledo-Piza and M. M. F. Marinho. 2013. Cyanogaster noctivaga, a remarkable new genus and species of miniature fish from the Rio Negro, Amazon basin (Ostariophysi: Characidae). Ichthyological Exploration of Freshwaters 23 (4) (for 2012): 297–318.

13 December

Cyanogaster noctivaga Mattox, Britz, Toledo-Piza & Marinho 2013

Some biological nomina are just perfect. They accurately describe the distinguishing features of the species in question. But then they do a little extra. They also describe some aspect of the species’ behavior or biology. And they do so with an interesting combination of Latin or Greek words. Cyanogaster noctivaga is one such name.

During an October 2011 expedition to Santa Isabel do Rio Negro (Amazonas State), a small village on the left bank of the upper Rio Negro in the Amazon basin, the authors collected several specimens of what they described as a “remarkable miniature fish,” not more than 17.4 mm long, and not assignable to any of the characid genera known at the time. The authors were struck by its large eyes, its odd-looking snout, mouth and teeth, its completely transparent body, and the iridescent blue color of its abdominal region.

“The fish appeared as a fast-swimming blue streak in the net,” Ralf Britz said.

One other odd or remarkable thing about the fish: They could only catch it at night.

Based on the shape and number of its teeth, Mattox et al. knew they had a new genus, to which they gave the name Cyanogaster: cyano, from kýanos, Greek for blue, and gastḗr, Greek for belly or stomach, referring to its conspicuous blue belly.

The specific epithet noctivaga is quite evocative. It’s a combination of nox, Latin for night, and vaga, from vagare, Latin for to wander, roam or walk about, referring to its presumed nocturnal habits.

In other words, the Blue-bellied Night Wanderer.

Biological nomina don’t get much better than that.

6 December

The gruesome legacy of Morton Allport

The Wikipedia entry (as of today) for Morton Allport (1830–1878) describes an “ardent and accomplished naturalist” who, “by his original work added largely to the knowledge of the zoology and botany of Tasmania.” The entry singles out his work with fishes and how he “made it his concern to send specimens of every new fish he could procure to the best authorities of England and elsewhere.” Indeed, six species have been named in honor of Allport, two of which remain valid today:

Splendid Sea Perch Callanthias allporti Günther 1876, found off southern Australia and New Zealand

Barred Grubfish Parapercis allporti (Günther 1876), found in the Eastern Indian Ocean, in southern Australia, from South Australia to New South Wales and Tasmania

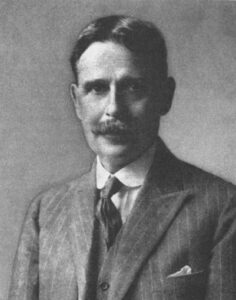

Morton Allport in 1854. © Allport Library and Museum of Fine Arts, State Library of Tasmania. The library/museum was founded by Morton’s grandson Henry Allport (1890-1965). The institution “respectfully acknowledges the lasting trauma experienced by Palawa/Tasmanian Aboriginal people that has resulted from the actions of Morton Allport and other individuals in the name of scientific research.”

Wikipedia does not mention that Allport was also a collector of human remains, specifically those of Aboriginal Tasmanian people, which he sent to European museums. According to new research published in the peer-reviewed journal Archives of Natural History, Allport resorted to graverobbing and corpse mutilation to collect these remains.

The paper, written by Jack Ashby, assistant director of the University of Cambridge Museum of Zoology, details a gruesome story involving the remains of William Lanne, who was thought to be the last Tasmanian Aboriginal man alive before his death in 1869. Lanne’s body was taken to a local hospital with plans for burial. But a man under Allport’s direction broke into the hospital and stole various parts of Lanne’s corpse. Later, Allport ordered the exhumation of Lanne’s grave to retrieve what was left of his skeleton.

Allport also served as vice president of the Royal Society of Tasmania. In 1878, the Society exhumed the hidden remains of Truganini, said to be the last-known surviving Tasmanian Aboriginal woman. Truganini had requested to be cremated to avoid having her remains become a museum exhibit but was buried anyway. The Royal Society displayed her skeleton until 1947.

These events occurred against a backdrop during which many Aboriginal women were being kidnapped by whalers, sealers and other settlers, and taken to islands where they were often tortured, enslaved and raped. There is no evidence that Allport participated in any of these crimes, but he certainly supported and benefited from a colonial government that allowed settlers to murder Tasmanian Aboriginal people without punishment. In fact, the number of Aboriginal people declined from around 6,000 in 1804 to fewer than 300 by the time Allport arrived in Tasmania. Their scarcity and near extinction increased the value of their remains and incentivized Allport to collect them even more.

Ashby’s study also recounts how Allport sought out the carcasses of thylacines — also known as Tasmanian tigers — which were being hunted into extinction because they were perceived to be a threat to livestock. (According to Ashby, the more likely culprit were dogs trained by colonists to hunt kangaroos.) When Allport sent these carcasses to European museums, he did not request money. Instead, he explicitly requested “quid pro quo” commendations for his efforts in the form of “accolades from elite international scientific institutions.” (The last surviving thylacine died in 1936.)

Allport’s story is another example of how 19th-century natural history collections are often linked with colonial genocide and brutality, and how natural history museums are grappling with the tainted legacies of their collections.

Details are not available of how Allport acquired the fishes for which he is named. Wikipedia – drawing on the Dictionary of Australasian Biography – described him as an “authority” on Tasmanian fishes who “catalogued, described and drew pictures of his specimens.” In addition, Allport is described as a “leader in the introduction of salmon and trout to Tasmanian waters and also introduced the white water-lily and the perch.” Today, exotic trout and salmon pose a major threat to the island’s endemic population of galaxiid fishes.

In addition to Ashby’s paper (link above), the University of Cambridge has posted a well-illustrated summary.

29 November

Amazonichthys Esguícero & Mendonça 2023

Women rule in the newly proposed tetra genus Amazonichthys.

First, there’s the generic name. Amazon refers not to the Amazon River basin of Brazil, where all three included species occur, but to the fabled Amazons of Greek mythology, a race of warrior women from which the Amazon gets its name. (Ichthys, of course, means fish.)

The name “Rio Amazonas” was reportedly first used when a native tribe, the Icamiabas, battled against Spanish troops led by Francisco de Orellana, a Spanish explorer and conquistador, in 1542. Orellana described the river as “the river of the Amazons,” referring to the mythical Amazons of Asia described in Greek legends, because the Icamiabas warriors were led by women. “Icamiabas” roughly translates as “broken breasts,” suggesting that the warriors’ right breasts were either flattened or mutilated for better use of a bow and arrow, just like the Amazons of Greek mythology.

The word “Amazon” itself may be derived from the Iranian compound ha-maz-an- “(one) fighting together” or ha-mazan “warriors.” Some scholars claim that the name is derived from the Tupi word amassona, meaning “boat destroyer.” Other derivations have also been proposed.

Just as the Amazons were an all-female tribe, Amazonichthys is an all-female genus: All three included species are named in honor of women.

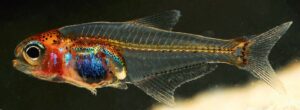

Amazonichthys lindae, holotype, 20.6 mm SL. From: Géry, J. 1973. New and little-known Aphyoditeina (Pisces, Characoidei) from the Amazon Basin. Studies on the Neotropical Fauna v. 8: 81–137.

The type species Amazonichthys lindeae was proposed as Axelrodia lindeae, by Jacques Géry in 1973. Géry named it in honor of Linde Geisler, who collected the holotype with German aquarist Rolf Geisler (1925–2012), presumably her husband. Ichthyologists have long known that this species is morphologically distinct from the other species of Axelrodia, with some authors questioning the monophyletic status of the genus. After a detailed study of the species, the authors of Amazonichthys erected a new genus for Axelrodia lindeae and described two new species, both named after modern-day “warriors” for conservation, education and women’s rights:

Amazonichthys camelierae is named in honor of Priscila Camelier, Universidade Federal da Bahia (Brazil), an “outstanding ichthyologist, passionate teacher, and strong women’s rights activist.”

Amazonichthys lu is named in honor of biologist Luciana Leite, known by her friends as “Lu,” for her “incredible enthusiasm and work towards the conservation of South American flora and fauna and for her endless fight in favor of women’s rights.”

Despite being an “all-female” genus, Amazonichthys is a grammatically masculine name. Why? Because in Latin, “ichthys” is a masculine noun.

For more information about Amazonichthys, see: Esguícero, A. L. H. and M. B. Mendonça. 2023. A new genus and two new species of tetras (Characiformes: Characidae), with a redescription and generic reassignment of Axelrodia lindeae Géry. Ichthyology & Herpetology 111, No. 3, 2023, 426–447.

22 November

An ETY-torial

Biological nomina are not monuments; they’re tools

Recent proposals to rename biological nomina on ethical and ideological grounds (see 24 March 2021 NOTW and 3 May 2023, below) reflect efforts among society at large to remove monuments that commemorate people associated with racism and imperialism, and to rename buildings, schools, streets and other locations named in their honor (e.g., Confederate statues in the U.S. and the “Rhodes Must Fall” movement in South Africa). But biological nomina are different from public-facing entities. They are not named by local government officials and community leaders. They are not named as an expression of a community’s shared values, and cannot be removed or changed when those values change. Biological nomina are created by biologists — often just one, sometimes a few, but never by consensus or committee — for use by other biologists. With the exception of serious amateur naturalists (aquarists, herpers, birders, butterfly collectors, etc.), the general public has little exposure to and awareness of the scientific names biologists use in their professional communications and publications.

Eleotris soaresi. Illustration by George Henry Ford. From: Playfair, R. L. and A. Günther. 1867. The fishes of Zanzibar, with a list of the fishes of the whole east coast of Africa. London. [Reprinted in 1971, with a new introduction by G. S. Myers and a new foreword by A. E. Gunther; Newton K. Gregg, publisher, Kentfield, California.]. i-xiv + 1-153, Pls. 1-21.

One thing I’ve learned since I began studying fish-name etymologies in 2009 is that most ichthyologists are not curious about the names of the fishes they’re studying. (If they were, The ETYFish Project would probably not exist.) Except for the names of taxa they describe themselves, most systematic studies of fishes do not include etymologies. In a recent redescription of Eleotris soaresi, the authors provide detailed morphometric data that confirm it as a valid species but do not explain the meaning of its name (Mennesson and Keith, 2020). I suspect that for them, “Eleotris soaresi” is not a monument to someone named Soares the same way a statue or the name of a building might be. It’s simply a name, a label on a museum jar, an entry in a checklist, a clade on a cladogram, a unique arrangement of letters that facilitates communications about this particular species and separates it from the other two million-plus named species of the world. Changing “soaresi” to something else would sever the link to Playfair’s original description and specimen. For biologists, the legacy of Playfair’s original description and specimen is more important than the legacy of the person for which it was named.

The sins of the past — slavery, genocide, racism, sexism, imperialism, colonialism — should not be ignored. But the wounds of these sins cannot be healed by changing the scientific names of plants and animals. They can only be healed by studying the past and making sure we don’t repeat it. The ETYFish Project has detailed the uncomfortable truths and regrettable histories behind many fish epithets. The path ahead is paved by knowing what came before.

15 November

Schindleria squirei Robitzch, Landaeta & Ahnelt 2023

In 1971, the progressive rock band Yes included a song called “The Fish (Schindleria praematurus)” on their album Fragile. Fifty-two years later, a new species of Schindleria has been named for the composer and featured soloist of that song, the band’s bassist and backing vocalist Chris Squire (1948-2015). Unfamiliar with the song, I had to check it out. And then I had to answer this burning question:

Why is there a song named for one of the most enigmatic little fishes in the world?

But first, some background regarding Schindleria.

Schindleria are pelagic reef fishes from the southern Pacific Ocean usually no more than 2 cm long. They’re called “infantfishes” because they retain larval features even as adults (a condition known as paedomorphosis). Their bodies are transparent and some of their bones do not develop. Yet despite their larval appearance they reproduce quickly and often, up to 7-9 generations per year. And despite their abundance — one study suggests they’re the most numerous coral-reef fishes in the world — infantfishes are seldom noticed because of their small size and transparency.

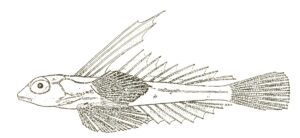

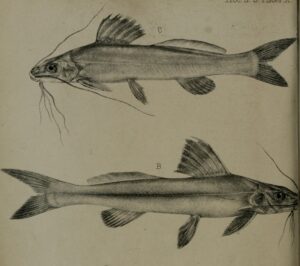

First-published images of Schindleria praematura, male above, female below. From: Schindler, O. 1932. Sexually mature larval Hemirhamphidae from the Hawaiian Islands. Bulletin of the Bernice P. Bishop Museum No. 97: 1-28, Pls. 1-10.

The first infantfish was described as Hemiramphus praematurus by German zoologist Otto Schindler (1906-1959) in 1930. Schindler was clearly puzzled by the fish, believing it to be a sexually mature larval halfbeak (hence its initial placement in Hemiramphus). The specific epithet, an adjective, connotes its premature (larval) appearance. Schindler described a second species the next year, Hemiramphus pietschmanni, naming it for ichthyologist Viktor Pietschmann (1881-1956), who collected the holotype. In 1934, Belgian ichthyologist Louis Giltay (1903-1937) questioned Schindler’s placement of the species in the family Hemiramphidae. Giltay created a new genus, Schindleria, and a new family, Schindleriidae, honoring Otto Schindler, but still wasn’t sure where to place them. He leaned towards Blenniiformes but wanted to devote time to study the issue. (He died three years later.) Subsequent researchers have since placed Schindleriidae within the goby order Gobiiformes. A 2009 phylogenetic analysis placed the genus within the goby family Gobiidae, thereby making Schindleriidae a junior synonym of Gobiidae. In other words, they’re paedomorphic gobies. The ETYFish Project follows this classification but Eschmeyer’s Catalog of Fishes does not.

According to one molecular analysis, there may be more than 30 cryptic species of Schindleria in the western Pacific. Since Schindler’s description of the second species in 1931, nine more species have been described — all since 2004 — including the most recent, Schindleria squirei, from Rapa Nui (Easter Island, Chile).

Unless you were an ichthyologist, Schindleria praematura (note the correct spelling of the adjectival specific epithet when placed in a feminine genus) was hardly a well-known fish in the early 1970s. So how did this larvae-like curiosity end up on the radar of a rock musician? And why did he name a song — actually an instrumental track with some singing of the fish’s name near the end — after it? Per Wikipedia and a few others sources, the story goes like this:

Chris Squire’s nickname was “The Fish.” He earned it because he took very long baths (a problem when the band shared a house in the early days of their career), and because his astrological sign was Pisces. Another reason is that Squire’s instrument and the low-frequency sound it generates — bass — is also the name of a fish. Squire apparently did not mind the nickname. His 1975 solo album is titled Fish Out of Water.

According to band lore, Squire had composed a melody and wanted to sing the name of a fish that was eight syllables long. Michael Tait, the band’s roadie, was dispatched to find one. Tait found the name Schindleria praematurus (still using the grammatically incorrect –us spelling) in a copy of the Guinness Book of World Records. (I believe S. prematura was considered the smallest known vertebrate at the time.) The rest, as they say, is musical history.

And now ichthyological history as well.

Footnote: In 2011, a species of fossil fish was named Tarkus squirei in Squire’s honor, referencing his nickname.

8 November

Gods and goddesses

Many fishes are named for Greek gods and goddesses. Eos (dawn). Pluto (underworld). Zephyrus (westerly wind). Hephaestus (fire). Hypnos (sleep). Thanatos (death). Selene (moon). Iris (rainbow). Nyx (night and darkness). Aphrodite (love and beauty). Hera (marriage, women and family). Apollo (music, poetry, medicine and archery). Poseidon (the sea).

These five are particularly interesting:

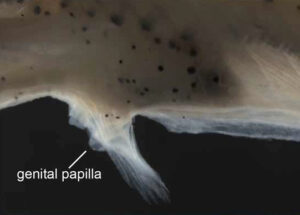

Danionella priapus, male holotype, 14.4 mm SL, close-up of modified pelvic fins and conically projecting genital papilla. From: Britz, R. 2009. Danionella priapus, a new species of miniature cyprinid fish from West Bengal, India (Teleostei: Cypriniformes: Cyprinidae). Zootaxa 2227: 53-60.

Danionella priapus Britz 2009 The five species of Danionella, found in freshwater habitats in Myanmar and India, are among the smallest vertebrates in the world, reaching just 10-15 mm. One species, known only from Jorai River, upper Brahmaputra River basin, East Bengal, India, is named for Priapus, the Greek god of fertility. The name refers to the conical projection of genital papilla in males, which superficially resembles the penis of mammals.

Danio aesculapii Kullander & Fang 2009 A close relative of Danionella priapus is Danio aesculapii, found in small freshwater streams on the western slope of Rakhine Yoma, Myanmar. It’s named for Aesculapius, the Greek god of medicine, who was equipped with a staff with one or two snakes wrapped around it. The allusion refers to the fish’s snakeskin pattern and the “snakeskin” epithet used in the European aquarium trade.

Trimma maiandros Hoese, Winterbottom & Reader 2011 This widespread pygmy goby from the Indo-Pacific is named for the Greek god of the winding Meander River in Phrygia (now the Büyük Menderes River in Turkey), and the origin of the Anglo-Saxon word meander (a winding or crooked course). It refers to the zigzag pattern of gray-to-blue lines on the goby’s body.

Pseudojuloides zeus, male holotype, 60 mm SL. Photo by Benjamin C. Victor. From: Victor, B. C. and J. M. B. Edward. 2015. Pseudojuloides zeus, a new deep-reef wrasse (Perciformes: Labridae) from Micronesia in the western Pacific Ocean. Journal of the Ocean Science Foundation 15: 41-54.

Pseudojuloides zeus Victor & Edward 2015 This deep-reef pencil wrasse from Palau and Majuro, Micronesia, is named for the Greek god Zeus, who cast bolts of lightning at unsuspecting mortals. The name refers to the wrasse’s jagged blue stripes on its sides, which resemble lightning bolts.

Varicus prometheus Fuentes, Baldwin, Robertson, Lardizábal & Tornabene 2023 This recently described goby from a deep reef off Roatan, Honduras, is named for the Greek god Prometheus, who, as punishment from the god Zeus, had his liver eaten out by an eagle, only to have the liver grow back overnight so it might be eaten again the next day. The name refers to the fact that the abdomen of the holotype was partially eaten by a hermit crab.

1 November

1 November

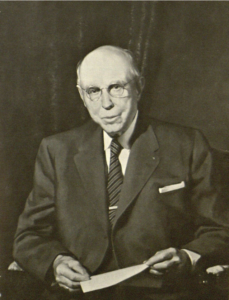

John R. Paxton (1938-2023)

John R. Paxton of the Sydney Museum (Australia) passed away early Sunday morning. He had been unwell for some months and passed in his sleep.

John was born in the USA in 1938. He completed his Ph.D. at the University of Southern California in 1968. Shortly thereafter, he succeeded Gilbert P. Whitley as Curator of Fishes at the Sydney Museum. John “retired” in 1998 but continued his research on deep-sea fishes as a Senior Fellow.

In an email informing colleagues of John’s passing, Amanda Hay, Collection Manager, Ichthyology, Australian Museum Research Institute, wrote:

“His legacy for the AMS Ichthyology collection is profound. Reorganizing the collection and bringing it into the modern era, he also set about a vigorous collecting program, not only of deep-sea fishes, but also coastal, estuarine and freshwater species and always encouraged the use of the collection. John mentored many students, teaching a popular ichthyology course at Macquarie University in the 1970s and supervising PhD, masters, and honours students.

“Building community nationally and internationally was key to John’s working life, bringing ichthyologists together to share knowledge. Alongside Doug [Hoese] they founded the Australian Society for Fish Biology in 1971 and the Indo-Pacific Fish Conference in 1981. John was a part of several iconic expeditions including Lord Howe Island in 1973, which contributed to Lord Howe Is being given a World Heritage listing and the first AM trip to Lizard Island.”

John had published over 100 scientific papers, including descriptions of 16 new species and nine new genera, and two major books: Encyclopaedia of Fishes (1994, with William Eschmeyer) and Fishes, Zoological Catalogue of Australia (2006).

Twenty fish species have been named in John’s honor:

NETTASTOMATIDAE

Nettenchelys paxtoni Karmovskaya 1999

ENGRAULIDAE

Setipinna paxtoni Wongratana 1987

ALEPOCEPHALIDAE

Conocara paxtoni Sazonov, Williams & Kobyliansky 2009

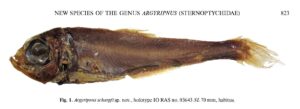

STERNOPTYCHIDAE

Polyipnus paxtoni Harold 1989

STOMIIDAE

Eustomias paxtoni Clarke 2001

Photonectes paxtoni Flynn & Klepadlo 2012

MACROURIDAE

Ventrifossa paxtoni Iwamoto & Williams 1999

Ventrifossa johnboborum Iwamoto 1982

CETOMIMIDAE

Cetomimus paxtoni Kobyliansky, Gordeeva & Mishin 2023

BYTHITIDAE

Bidenichthys paxtoni (Nielsen & Cohen 1986)

SYNGNATHIDAE

Corythoichthys paxtoni Dawson 1977

CALLIONYMIDAE

Synchiropus paxtoni Fricke 2000

GEMPYLIDAE

Rexichthys johnpaxtoni Parin & Astakhov 1987

CHIASMODONTIDAE

Pseudoscopelus paxtoni Melo 2010

MALACANTHIDAE

Branchiostegus paxtoni Dooley & Kailola 1988

GIGANTACTINIDAE

Gigantactis paxtoni Bertelsen, Pietsch & Lavenberg 1981

TETRAODONTIDAE

Torquigener paxtoni Hardy 1983

OSTRACOBERYCIDAE

Ostracoberyx paxtoni Quéro & Ozouf-Costaz 1991

ANTHIADIDAE

Acanthistius paxtoni Hutchins & Kuiter 1982

LIPARIDAE

Careproctus paxtoni Stein, Chernova & Andriashev 2001

In addition, a subfamily and genus have been named for Paxton as well:

APOGONIDAE Subfamily Paxtoninae

Paxton Baldwin & Johnson 1999

named for friend and colleague John R. Paxton, Australian Museum (Sydney), who provided type specimens, as a “good-natured reminder that ‘you can’t judge a fish by its cover’” (Paxton initially believed that the specimens represented an undescribed genus of grammastin serranid]

Hoplocharax goethei. From: Géry, J. 1966. Hoplocharax goethei, a new genus and species of South American characoid fishes, with a review of the sub-tribe Heterocharacini. Ichthyologica, the Aquarium Journal 38 (3): 281–296.

25 October

Hoplocharax goethei Géry 1966

French plastic surgeon-turned-ichthyologist Jacques Géry (1917–2007) described Hoplocharax goethei, a biting tetra (Acestrorhynchidae) from the Amazon and Orinoco basins of Brazil and Colombia in 1966. He named it after the recently deceased Charles M. Goethe (1875–1966) of Sacramento, California, USA, “for his support of scientists and students in the fields of biology, conservation, and education.” Géry did not explain the support Goethe had provided, nor whether he himself had any association with him. It’s interesting to note, however, that Géry’s ichthyological colleague Martin R. Brittan (1922–2008) — whom Géry thanked in the description — taught at Sacramento State College. Brittan certainly was familiar with Goethe, and perhaps even knew him, since Goethe founded Sacramento State College (now California State University, Sacramento, or CSUS) in 1947, and regularly gave the college money for research projects and library acquisitions, including a large endowment after his death.

Portrait of Charles M. Goethe from a booklet produced for “C.M. Goethe National Recognition Day,” March 28, 1965.

In return for his money, the college turned a blind eye to Goethe’s widely known support of eugenics, and his admiration for Nazi Germany. He was fascinated by the “science” of “racial hygiene.” He dismissed early reports on Hitler’s racial policies as liberal and Jewish propaganda. In fact, he said the Nazi sterilization program was “administered wisely, and without racial cruelty.” And one of his last financial donations, made three months before his death, was to a white supremacist organization in the Netherlands working to build “cooperation between all the Nordic Peoples” — “the best, most intelligent and highest cultured Peoples of the world” — against the “worthless peoples of Africa and Asia.”

In 1965, CSUS announced with great fanfare that it was naming its new science building after Goethe. Students and faculty protested, comparing Goethe to Dr. Strangelove, the eponymous ex-Nazi in Stanley Kubrick’s 1964 black comedy film. CSUS officials accused the protesters of libel but later quietly dropped Goethe’s name from the building.

It’s not known whether Géry knew any of this when he described the species, but Brittan almost certainly did. Goethe was very public about his beliefs. They were an open secret on campus. As long as he kept writing checks, CSUS was more than happy to cash them.

In 2005, CSUS changed the name of its Charles M. Goethe Arboretum to University Arboretum. No official reason was given, but everybody knew why.

A note on Hoplocharax: Géry proposed Hoplocharax as a new monotypic genus for H. goethei. The second half of the name is from Charax, typical genus of the Characiformes, from chárax (Gr. χάραξ), a pointed stake of a palisade, referring to densely packed sharp teeth, a common root-name formation in the order. The first half is from hóplon (Gr. ὅπλον), shield or armor (but here meaning armed), which Géry said referred to the fish’s strong and pointed pectoral fin spine and its three opercular spines. Curiously, Géry did not mention the dorsal and ventral spines on the caudal peduncle, clearly evident in his illustration (shown above).

Akysis bilustris, holotype, 25.3 mm SL. From: Ng, H. H. 2011. Akysis bilustris, a new species of catfish from southern Laos (Siluriformes: Akysidae). Zootaxa 3066: 61-68.

18 October

10th anniversary NAME OF THE WEEK

Akysis bilustris Ng 2011

Two days ago, 16 October, marked the 10-year anniversary of The ETYFish Project going online and the first weekly “Name of the Week” posting (about the Umpqua Chub Oregonichthys kalawatseti). I wanted to commemorate the milestone by featuring a fish name that had something to do with 10 years. For example, a 10th wedding anniversary gift is traditionally tin or aluminum, symbolizing the strength and resilience of marriage. So, I scoured ETYFish entries to see if a fish has been named for having a tin- or aluminum-like color or appearance. I couldn’t recall any offhand but, with 42,806 entries to date, I sometimes forget about names I researched, you know, a decade ago. I found no references to tin and only one for aluminum: a fish whose description was financed by an aluminum production company!

I then turned to names based on the Greek word dekas, meaning 10. There are many such names for fishes with 10 spines, 10 fin rays, 10 lateral-line canals, that sort of thing. They’re all perfectly fine names but perhaps a bit too utilitarian to list and discuss here.

And then I recalled a fish that’s actually named for a decade. And so, I feature it this week:

Akysis bilustris is a catfish (Akysidae) from the Mekong River drainage in southern Laos. It was described by Heok Hee Ng, an expert in Asian catfishes at the Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum of the National University of Singapore. The specific epithet is a Latin adjective that means “that lasts 10 years,” from bi-, meaning two, and lustrum, a period of five years. In other words, a decade.

Why a decade?

Because the specimens that Ng used to describe the new species were collected in two expeditions exactly 10 years apart: 22 May 1999 and 22 May 2009.

Here’s to another 10 years of ETYFish!

11 October

11 October

Heteronarce bentuviai (Baranes & Randall 1989) in honor of Polish-born Israeli ichthyologist Adam Ben-Tuvia (1919–1999), Hebrew University of Jerusalem, for his valuable contributions to the knowledge of Israeli fishes

Etrumeus golanii DiBattista, Randall & Bowen 2012 in honor of Israeli ichthyologist Daniel Golani, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, who provided type specimens, genetic material and a photograph of the holotype

Nun Bănărescu & Nalbant 1982 Aramaic (the language of the Talmud) word for fish (in this case, Nun galilaeus, described from Israel)

Acanthobrama lissneri Tortonese 1952 in honor of the late Helmut Lissner (1895–1951), Polish-born Israeli ichthyologist, a “keen ichthyologist who greatly furthered the investigations on the fishes of Lake Tiberias” (or Sea of Galilee), Israel, type locality

Acanthobrama telavivensis Goren, Fishelson & Trewavas 1973 –ensis, Latin suffix denoting place: Tel Aviv, Israel, near type locality at Yarkon Springs

Mirogrex hulensis Goren, Fishelson & Trewavas 1973 –ensis, Latin suffix denoting place: Lake Huleh, Israel, type locality (now extinct due to deliberate draining of lake in the 1950s)

Mirogrex terraesanctae (Steinitz 1952) of terra (L.), land, and sanctus (L.) holy, i.e., the Holy Land, referring to Lake Tiberias (or Sea of Galilee), Israel, where it is endemic

Siphamia goreni Gon & Allen 2012 in honor of Menachem Goren, Tel-Aviv University (Israel), who collected type, for his contribution to our knowledge of Red Sea fishes

Amblyeleotris steinitzi (Klausewitz 1974) in honor of the late Heinz Steinitz (1909–1971), marine biologist, herpetologist, and founder of the marine laboratory that bears his name, in Eilat, Israel, on the Gulf of Aqaba, where this goby occurs

Callogobius amikami Goren, Miroz & Baranes 1991 in honor of Amikam Gorovitch (no other information available), who was killed in a diving accident in Eilat, Israel, type locality

Hazeus elati (Goren 1984) of Elat (also spelled Eilat), Gulf of Aqaba, Red Sea, northern Red Sea, Israel, type locality

Priolepis goldshmidtae Goren & Baranes 1995 in honor of Ms. Orit Goldshmidt, Interuniversity Institute of Marine Sciences (Eilat, Israel), who collected holotype

Trimma mendelssohni (Goren 1978) in honor of Heinrich Mendelssohn (1910–2002), Tel Aviv University, for his “invaluable” contributions to zoological research and nature conservation in Israel

Astatotilapia flaviijosephi (Lortet 1883) in honor of Titus Flavius Josephus (37–c. 100), Romano-Jewish scholar, historian and hagiographer, who is mentioned several times in Lortet’s study of Lake Tiberias (Sea of Galilee in Israel); Flavius reported a thriving fishing industry on the lake and believed the occurrence of a catfish (Clarias gariepinus) in the lake was due to underground connections to the Nile

Sarotherodon galilaeus (Linnaeus 1758) –eus, Latin adjectival suffix: referring to Sea of Galilee (Lake Tiberias), Israel, type (now lost) locality

Tristramella sacra (Günther 1865) sacred, referring to Lake Tiberias (Sea of Galilee), Israel, type locality, in an area generally known as the “Holy Land”

Pseudochromis fridmani Klausewitz 1968 in honor of reef biologist David Fridman, Maritime Museum (Eilat, Israel), who collected holotype

Aseraggodes steinitzi Joglekar 1971 in honor of Heinz Steinitz (1909–1971), marine biologist, herpetologist, and founder of the marine laboratory that bears his name, in Eilat, Israel, on the Gulf of Aqaba, who sent specimens from the Red Sea and information about type locality

Dunckerocampus multiannulatus bentuviae Fowler & Steinitz 1956 in honor of ichthyologist Adam Ben-Tuvia (1919–1999), Hebrew University of Jerusalem, who collected type and contributed “interesting and valuable field notes” for many of the fishes Hebrew University and the Israel Sea Fisheries Research Station donated to the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia

Evoxymetopon moricheni Fricke, Golani & Appelbaum-Golani 2014 in honor of Mordechai (“Mori”) Chen, who found holotype drifting dead while snorkeling in the northern Gulf of Aqaba, Red Sea, in Israel; at first, he imagined the long, shiny object to be a strip of metal

Hoplolatilus oreni (Clark & Ben-Tuvia 1973) in honor of Oton H. Oren (1921–1983), chemist and oceanographer, Haifa Sea Fishery Research Station (Israel), who “helped in the collection of many Red Sea fishes”

Parascolopsis baranesi Russell & Golani 1993 in honor of Albert (Avi) Baranes (b. 1949), Director of the Interuniversity Institute for Marine Sciences (Eilat, Israel), through whose efforts this species was collected in the Gulf of Aqaba

Hyporthodus haifensis (Ben-Tuvia 1953) –ensis, Latin suffix denoting place: Sea Fisheries Research Station at Haifa, Israel, near Caesarea, Mediterranean Sea, type locality

Pterygotrigla spirai Golani & Baranes 1997 in honor of neurobiologist Micha E. Spira, founding Scientific Director of Interuniversity Institute for Marine Sciences (now Alexander Silberman Institute of Life Sciences, Elat [also spelled Eilat], Israel), for his contribution to marine science research in the Red Sea

4 October

Rineloricaria cachivera Urbano-Bonilla, Londoño-Burbano & Carvalho 2023

Paratypes of Rineloricaria cachivera. (a) Unpreserved specimen, río Vaupés at Resguardo Trub on. (b-c) MPUJ 14481, 114.4 mm standard length (LS), río Vaupés at Laguna Arcoiris small rocky bottom isolated lagoon from the river, Comunidad de Matapí, Mitú, Vaupés, Colombia. From: Urbano-Bonilla, A., Londoño-Burbano, A., & Carvalho, T. P. (2023). A new species of rheophilic armored catfish of Rineloricaria (Siluriformes: Loricariidae) from the Vaupés River, Amazonas basin, Colombia. Journal of Fish Biology, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfb.15500

On 2 March 2019, Colombian ichthyologist Javier Alejandro Maldonado-Ocampo and two other researchers were crossing the swift, rocky waters of the Río Vaupés of Colombia when their small boat overturned. The two researchers made it to safety, but Maldonado-Ocampo was swept downstream. On Sunday, March 5, 73 kilometers from the accident site, his body was recovered by Brazilian soldiers who had joined the search party. Dr. Maldonado-Ocampo was 42 years old. (See NOTW, 13 March 2019.)

Two days before his tragic death, Maldonado-Ocampo — nicknamed “Nano” — collected a rheophilic (preferring or living in flowing water) armored catfish from the rapids of the río Vaupés. He collected it by hand, underwater in the rapids, wearing a diving mask. Over three years later, on 2 Aug. 2023, this catfish was formally described as a new species, Rineloricaria cachivera.

“Cachivera” is Spanish for a “flow of water that runs violently between the rocks” (i.e., rapids). “In the cosmology of the indigenous peoples of the Vaupés,” the authors write, “the waters of its rivers are inhabited by various supernatural creatures that must be venerated, consulted, and appeased in the rituals of the shamans; these creatures live and guard mainly the cachiveras of the rivers where humans are more fragile and face the greatest danger …”.

The catfish was named in memory of Maldonado-Ocampo, who, on 2 March 2019, the authors say, “stayed forever swimming in peace and happy with the rheophilic fish of the cachiveras of the Vaupés River.”

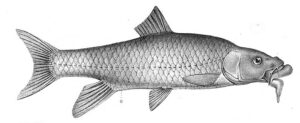

Cherry Barb, Rohanella titteya. From Innes’ Exotic Aquarium Fishes.

27 September

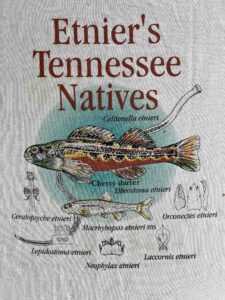

Rohanella Sudasinghe, Rüber & Meegaskumbura 2023

Rohanella is a monotypic genus recently proposed to accommodate the Cherry Barb, formerly known as Puntius titteya. The name is a Latin diminutive (-ella, which usually connotes endearment), in honor of Sri Lankan biologist Rohan Pethiyagoda (b. 1955).

Pethiyagoda was honored for two reasons: for recognizing (in 2012) that two species of Puntius, a catch-all genus for small barbs from Asia — P. titteya and P. bimaculata — warranted separate genera, and for his contributions to biodiversity research and guidance of young biodiversity researchers in Sri Lanka. (P. bimaculata is now in its own genus, Plesiopuntius, proposed by the same authors. In addition, they proposed the new genus Bhava for Puntius vittatus.)

It’s been an eventful year for Pethiyagoda. In June, he published a stinging rebuke of the efforts to exorcise biological nomenclature by changing scientific names, particularly eponyms, deemed offensive because they honor people historically connected to eras of imperialism and colonialism and/or who advocated sexist, racist, white supremacist, or pro-slavery views. (See the 24 March 2021 and 3 May 2023 [below] NOTWs for my views on revisionist nomenclature.)

In 2022, Rohan Pethiyagoda won the prestigious Linnean Medal of the Linnean Society of London, becoming the first Sri Lankan and only the second Asian to receive this award since its inception in 1888.

Pethiyagoda’s take is notable because he is writing from the perspective of a scientist who has spent most of his career in Sri Lanka, a developing country. He contends that “undoing the perceived harm that inappropriate names and terms can cause people who belong to oppressed communities in the developed world (the West) may harm the greater part of the global scientific community whose native language is not English.” In other words, biologists are seeking to “redress social problems in the English-speaking world … by imposing terminological and nomenclatural reforms also on the rest of the world.”

A few highlights from Pethiyagoda’s editorial:

On efforts to replace “colonial” names with indigenous names:

The 26-letter Latin alphabet is simply too restricted phonetically, as is clear from myriad potentially offensive historical transliterations such as ceylonensis [from Saheelan, a Persian name for the island: Imam, 1990], maderaspatensis [from Madrasan], and bombayensis [from Mumbai]. People in these countries know that these epithets are semantically flawed, but I have encountered no one who says their feelings are hurt by these historical errors.

On efforts to rename taxa named by authors suspected of unethical behavior:

Pethiyagoda (2021) highlighted 15 taxonomic papers published since 2018, involving a total of more than 3500 specimens belonging to some 80 species, all illegally collected and smuggled out of Sri Lanka. Should these publications be retracted? Should the new taxa described be invalidated? Perhaps they should, but the principal consequence of such actions would be the destabilization of biological nomenclature.

On efforts to rename eponyms:

In the absurd logic of Guedes et al. (2023), we must now rename physical units such as the Ampere, Celsius, Fahrenheit, Hertz, Joule, Kelvin, Newton, Volt and Watt; well-known minerals such as Alexandrite and Dolomite; popular garden plants such as Albizia, Banksia, Begonia, Bougainvillea, Camellia, Dahlia, Gardenia, Magnolia, Poinsettia and Wisteria; medically important organisms such as Escherichia, Klebsiella, Rickettsia and Salmonella; medical eponyms such as Alzheimer’s, Asperger’s, Hodgkin’s, Parkinson’s, Rorschach and Heimlich; geographic features such as Mount Everest and the Mariana Trench; and words in common use such as sandwich, diesel and pasteurize.

I could go on, but Pethiyagoda’s editorial is a free download. I highly recommend it.

Adult holotype of Monomitopus ainonaka and a larval Monomitopus spp. (captured and photographed by A. Deloach, N. Deloach, and S. Kovacs) in Ianniello’s coil. From: Girard, M. G., H. J. Carter and G. D. Johnson. 2023. New species of Monomitopus (Ophidiidae) from Hawaiʻi, with the description of a larval coiling behavior. Zootaxa 5330 (no. 2): 265-279.

20 September

Monomitopus ainonaka Girard, Carter & Johnson 2023

The recent description of Monomitopus ainonaka, a new species of cusk eel (Ophidiidae), highlights, say its describers, the “importance of blackwater photography in advancing our understanding of marine larval fish biology.”

Blackwater diving is nightime SCUBA diving in water at least 180 m deep. The ocean is pitch black. At around 20 m, you drift with the current, as countless numbers of ocean creatures — primarily plankton and larval fishes that look nothing like their adult forms — ascend from the depths towards the surface (termed Diel Vertical Migration) to eat (or be eaten). At dawn they retreat to the depths. Blackwater photography is the art of capturing these creatures on film. These images allow biologists to see their intricate and delicate structures in situ and intact, prior to being damaged by nets and fixation in ethanol.

In 2021, blackwater divers photographed and collected a 14.4 mm SL larval fish with a large head and tapering body off the coast of Kona, Hawaiʻi. The authors identified it as a species of the genus Monomitopus but its DNA barcode did not match any of the six previously sequenced species within the genus. The authors then found a single unidentified specimen of Monomitopus collected North of Maui, Hawaiʻi, in 1972, within the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History Vertebrate Zoology Fishes Collection. Its fin-ray and vertebral/myomere counts overlapped those of the larval Hawaiian specimen. Based on these two specimens, the species was described as new. The authors named it Monomitopus ainonaka, in honor of Ai Nonaka, United States National Museum (and the third author’s wife), for her interest in ophidiid larvae and dedication to the discovery, identification and curation of larval fishes.

The name of the genus Monomitopus — proposed by British physician-naturalist Alfred William Alcock (1859-1933) in 1890 — translates as mono– (one), mitos (thread) and pus (from pous, foot), referring to how the ventral fin-rays of M. nigripinnis are fused to form a single filament.

In addition, blackwater photographs of the Hawaiian larva, two newly identified larvae of M. agassizii, and several uncollected larval Monomitopus, show the larvae contorting their bodies into a tight coil. The authors call this “Ianniello’s coil,” named after blackwater photographer Linda Ianniello for documenting a long behavioral sequence of M. agassizii and for her willingness to share her knowledge and images of larval fishes.

Ianniello explains her technique and her working relationship with scientists in this 6-minute video.

Other larval marine fishes coil their bodies, usually in response to a perceived threat (e.g., camera lights). Researchers have proposed that coiling is a form of Batesian Mimicry, whereby larvae are mimicking nutritionally poor gelatinous zooplankton (e.g., cnidarians, ctenophores, salps) to avoid predation. Larval Monomitopus, however, are found coiled most of the time. More research is needed to confirm the mimicry hypothesis.

13 September

Parabotia: Masculine or feminine?

The name of the loach genus Botia Gray 1831 is considered to be feminine in gender. This means that any specific epithets that are adjectives must be spelled to agree with the feminine gender. For example, the species Botia rostrata Günther 1868 — Latin for beaked — is spelled rostrata (feminine) instead of rostratus (masculine) or rostratum (neuter).

Since Botia is feminine, it stands to reason that subsequently described genus-level names ending in “-botia” should be feminine as well. And they are:

Leptobotia Bleeker 1870

Gobiobotia Kreyenberg 1911

Sinibotia Fang 1936

Chromobotia Kottelat 2004

Yet the loach genus Parabotia Guichenot 1872 is considered masculine. Why?

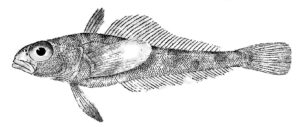

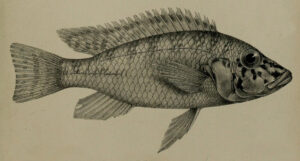

Botia almorhae. From: Day, F. 1878. The fishes of India; being a natural history of the fishes known to inhabit the seas and fresh waters of India, Burma, and Ceylon. Part 4: i-xx + 553-778, Pls. 139-195.

British naturalist John Edward Gray (1800-1875) did not indicate the gender of Botia when he proposed the genus for Botia almorhae, a loach from Almorha (now spelled Amora), Uttar Pradesh, India, in 1831. Nor did he explain what “Botia” means. However, Scottish physician-naturalist Francis Hamilton (1762–1829) used the same term for another Indian loach, Cobitis (now Paracanthocobitis) botia, described in 1822. Hamilton indicated that the local Assamese name for this species was “balli-potia,” which he apparently shortened to “botia.” (Note: several aquarium websites state that Botia is an “Asian” word for warrior or soldier but do not provide a source.)

The Code of the International Commission of Zoological Nomenclature provides a four-step process for determining the gender of genus-level names not formed from Latin or Greek.

ICZN 30.2.1. If a name reproduces exactly a noun having a gender in a modern European language (without having to be transliterated from a non-Latin alphabet into the Latin alphabet) it takes the gender of that noun.

Botia does not. So we go to step two:

ICZN 30.2.2. A name that is not formed from a Latin or Greek word takes the gender expressly specified by its author.

Gray did not specify a gender. So we go to step three:

ICZN 30.2.3. The name takes the gender indicated by its combination with one or more adjectival species-group names of the originally included nominal species

The species name Gray proposed, Botia almorhae, is a noun in the genitive (Almora’s Botia), not an adjective. So we go to the fourth and final step:

ICZN 30.2.4. If no gender was specified or indicated, the name is to be treated as masculine, except that, if the name ends in –a the gender is feminine, and if it ends in –um, –on, or –u the gender is neuter.

Botia ends in the letter “a”. So it’s feminine.

When Dutch ichthyologist Pieter Bleeker (1819–1878) proposed the genus Leptobotia (slender Botia) in 1870, he indicated that he regarded the genus as feminine by naming the type species Leptobotia elongata (instead of elongatus or elongatum).

German physician-naturalist Martin Kreyenberg (1872–1914) proposed the gudgeon genus Gobiobotia — i.e., a Botia-like Gobio — in 1911. In this case, step four — ending in “a” — indicates the genus as feminine.

Chinese ichthyologist Fang Ping-Wen (1903–1944) proposed Sinibotia (Sino- or Chinese Botia) in 1936. The name of the type species S. superciliaris is an adjective, but both the masculine and feminine spellings are the same (-is) and therefore not instructive for determining gender. Since Fang proposed Sinibotia as a subgenus of Botia, it’s safe to assume that the gender of the former informs the gender of the latter. If not, then step four — ending in “a” — confirms the genus as feminine.

Swiss ichthyologist Maurice Kottelat — an expert in zoological nomenclature and the grammar of zoological Latin — left nothing to chance. When he proposed Chromobotia (colorful Botia) for the popular Clown Loach C. macracantha of aquaria in 2004, he unambiguously indicated the genus as feminine.

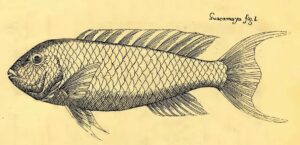

Parabotia fasciatus. From: Dabry de Thiersant, P. 1872. Nouvelles espèces de poissons de Chine. In: Dabry de Thiersant, P. La pisciculture et la pêche en Chine. G. Masson. Paris. 195 pp. 178-192, Pls. 36-50.

Which brings us to Parabotia (near or close to Botia), proposed by French zoologist Antoine Alphone Guichenot (1809-1876) in 1872. (Note: the name is often attributed to Claude-Philibert Dabry de Thiersant, who published Guichenot’s description.) Following the four steps described above, we come to ICZN step three. Guichenot included two nominal species in the genus: P. fasciatus and P. rubrilabris. “Rubrilabris” (red lip) is a noun in apposition, which doesn’t help us. But Guichenot proposed “fasciatus” (banded), an adjective, with a masculine declension. Therefore, the gender of Parabotia is masculine per ICZN 30.2.3.

Recently, a team of ichthyologists, in an annotated checklist of Russian fresh- and brackish-water fishes, argued that Parabotia should be treated as feminine because the name ends with the letter “a,” citing ICZN 30.2.4. Unfortunately, it appears they were not aware that ICZN 30.2.4 can only be evoked if ICZN 30.2.3 does not apply.

As Maurice Kottelat said in 2013, “This is unfortunate, since all other genus names ending in –botia are feminine, but it cannot be changed.”

6 September

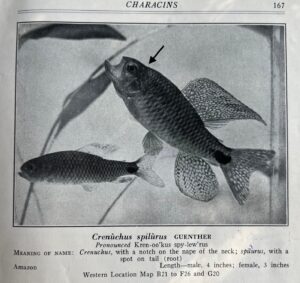

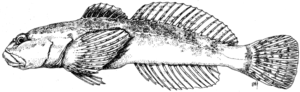

Crenuchus spilurus Günther 1863

Crenuchus spilurus, the Sailfin Tetra, occurs in acidic backwaters of the Amazon and Orinoco basins of South America. It is the only member of its genus. Both the genus and the species were proposed by ichthyologist-herpetologist Albert Günther (1830-1914) of the British Museum (Natural History). As per his custom, Günther did not explain the meanings of the names.

The specific epithet spilurus is easy to figure out. It’s a common name in ichthyology, a combination of the Greek words spílos, mark or spot, and urus, a Latinization of the Greek ourá, tail. It means “spot-tailed,” referring to the round black spot at the caudal peduncle.

The specific epithet spilurus is easy to figure out. It’s a common name in ichthyology, a combination of the Greek words spílos, mark or spot, and urus, a Latinization of the Greek ourá, tail. It means “spot-tailed,” referring to the round black spot at the caudal peduncle.

The generic name Crenuchus, however, has proven difficult. According to FishBase, the name is derived from the Greek krenoychos, the “God of running waters.” Several aquarium websites say it means “guardian of the spring.” Both of these explanations have been copy-pasted and re-posted multiple times. How the name applies to the fish is not explained.

“Krenoychos” appears to be an alternate spelling of the Greek krēnoū́chos (κρηνούχος), which means “ruling over springs.” The word is associated with Poseidon, the Olympian god of the sea. In some ancient cults, Poseidon was worshipped as Krenouchos, who, with the strike of his trident, created springs and thus was the source of fresh (i.e., running) water.

Is “Krenoychos” an allusion to the fish’s habitat? Maybe. But Günther likely described it from a specimen in a jar and probably knew little or nothing from where it was collected other than the Essequibo River of Guyana.

I propose a far less fanciful explanation for Crenuchus: a combination of the Latin crena, meaning notch, and the Medieval Latin nuchus, from nucha, the nape of the neck (from whence the English adjective nuchal derives). William T. Innes reached the same conclusion in his classic Exotic Aquarium Fishes (the book that got me interested in ichthyo-etymology): “with a notch at the nape of neck.”

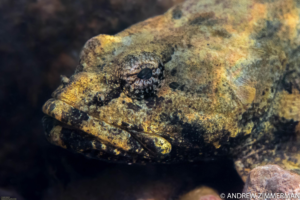

It would be helpful if Günther had mentioned this character in his very brief description, or in a more-detailed description that followed in 1864. He did not. But a museum photograph of the holotype (BMNH 1864.1.21.92) that Günther examined (shown here) does show a separation between the nape and back that may be a damaged remnant of a nuchal notch or indentation.

It would be helpful if Günther had mentioned this character in his very brief description, or in a more-detailed description that followed in 1864. He did not. But a museum photograph of the holotype (BMNH 1864.1.21.92) that Günther examined (shown here) does show a separation between the nape and back that may be a damaged remnant of a nuchal notch or indentation.

What’s more, Innes’ photograph of Crenuchus spilurus (shown above, with an added arrow) clearly shows a small notch in the nape or neck of a nuptial male.

My explanation is still speculation, of course, but at least it’s informed speculation. Nothing about “Krenoychos” seems to fit. And it may be worth noting that Günther was not given to classical allusions and metaphors in the epithets he coined.

There is a loose end I should mention in the interests of full disclosure. In Brown’s Composition of Scientific Words, the –uchus half of Crenuchus is said to be from the Greek echo, meaning “hold, carry.” The “cren-” half of the name is not explained, but krene is Greek for spring (the water body, not the device or season). I translate the name as “spring-bearing,” but that doesn’t make sense. If we translated “cren-” as the Latin crena (“notch”), then “notch-bearing” makes more sense based on what we know about the fish.

30 August

Chiloglanis frodobagginsi Schmidt, Friel, Bart & Pezold 2023

Chiloglanis frodobagginsi. From: Schmidt, R. C., P. H. N. Bragança, J. P. Friel, F. Pezold, D. Tweddle and H. L. Bart Jr. 2023. Two new species of suckermouth catfishes (Mochokidae: Chiloglanis) from Upper Guinean forest streams in West Africa. Ichthyology & Herpetology 111 (3): 376-389.

For the 21 October 2020 “Name of the Week,” we provided a list of fish taxa inspired by characters and places in J. R. R. Tolkien’s Middle Earth legendarium:

Gollum

Durin the Deathless

The Balrogs

Azaghâl, king of the Broadbeam Dwarves

The River Bruinen

Lórien, the realm of the Elves

Galadriel, the elf ruler of Lothlórien (or Lórien)

This week we add another.

Chiloglanis frodobagginsi is a new species catfish from the upper Niger River of Guinea. It is named for Frodo Baggins, a Hobbit of the Shire, who inherits the One Ring from his cousin Bilbo. Aware of the Ring’s malevolent power, Frodo embarks on a long journey to destroy it in the fires of Mount Doom in Mordor. His journey took 185 days, covering a distance of approximately 1800 miles (2897 km).

Chiloglanis frodobagginsi is, per its describers, another “incredible traveler.” Like Frodo, it is small (reaching 38.1 mm SL). And like Frodo, it too embarked on a long journey — or at least its progenitors did. C. frodobagginsi occurs in the Niger River basin, Guinea. It was previously considered to be a disjunct population of C. micropogon, found in the Congo River basin of Angola and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, roughly 4800 km away. Another seemingly closely related (and undescribed) species similar to C. micropogon is found in the southern Benue drainage and in several small coastal rivers about 3,000 km from the upper Niger River drainage. It is unclear whether these species are descended from a more widespread species, or are the result of dispersal from the Congo River basin into the Niger River drainage, via the Benue River, and then up to the headwaters of the Niger River. If they dispersed, the authors say …

Chiloglanis frodobagginsi is, per its describers, another “incredible traveler.” Like Frodo, it is small (reaching 38.1 mm SL). And like Frodo, it too embarked on a long journey — or at least its progenitors did. C. frodobagginsi occurs in the Niger River basin, Guinea. It was previously considered to be a disjunct population of C. micropogon, found in the Congo River basin of Angola and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, roughly 4800 km away. Another seemingly closely related (and undescribed) species similar to C. micropogon is found in the southern Benue drainage and in several small coastal rivers about 3,000 km from the upper Niger River drainage. It is unclear whether these species are descended from a more widespread species, or are the result of dispersal from the Congo River basin into the Niger River drainage, via the Benue River, and then up to the headwaters of the Niger River. If they dispersed, the authors say …

“This was an incredible journey for such a small and seemingly non-vagile fish.”

A second species of Chiloglanis is described in the same paper. It also has an interesting name. Chiloglanis fortuitus is named for the “fortuitous aspect” of collecting the only known specimen, and its “discovery” in a lot of specimens borrowed by the lead author as he was describing C. tweddlei in 2017.

For an interesting look at the presumed actual fishes of Middle Earth, ichthyologist Philip W. Willink of the Field Museum in Chicago has prepared a handy field guide.

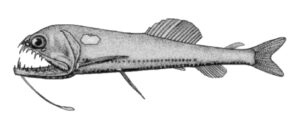

Rhynchobatus luebberti. From: Ehrenbaum, E. 1915. Über Küstenfische von Westafrika, besonders von Kamerun. L. Friederichsen & Co., Hamburg. 1-85 pp. Bottom image shows tip of the head from below (p. 70).

23 August

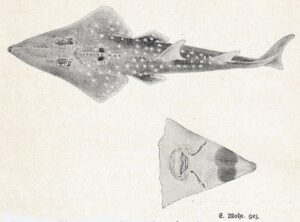

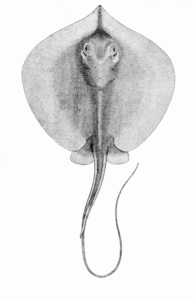

Rhynchobatus luebberti Ehrenbaum 1914*

(written with Holger Funk)

In recent years, biologists have been reassessing and debating the ethical appropriateness of biological nomina named after people associated with racism, colonialism, imperialism, slavery and other social ills. Some of these biologists have even called for the elimination and replacement of eponyms altogether, a notion rejected in the 3 May 2023 Name of the Week. Yes, eliminating eponyms would effectively “cancel” the names of plants and animals named after proponents of racism. But it would also “cancel” the names of organisms named after people whose careers and reputations were destroyed by institutionalized racism as well. The name of the African Wedgefish Rhynchobatus luebberti (also known as Lubbert’s Wedgefish) is a case in point.

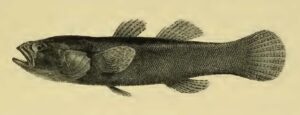

Ernst Ehrenbaum (1861–1942)

Rhynchobatus luebberti is a critically endangered species that occurs in shallow coastal waters in the Eastern Atlantic from Congo to Mauritania. It was described by Ernst Ehrenbaum (1861-1942), a German ichthyologist and oceanographer, in his well-illustrated 1915 book Über Küstenfische von Westafrika, besonders von Kamerun (On coastal fishes from West Africa, especially from Cameroon). With the epithet luebberti, the author honored his friend and colleague Hans Julius Lübbert (1870–1951), a German fisheries inspector and director with whom he had been publishing the periodical Der Fischerbote (The Fishers’ Messenger) in Hamburg since 1910 and the collective volumes Handbuch der Seefischerei Nordeuropas (Manual of Sea Fishing in Northern Europe) since 1926. Ehrenbaum and Lübbert had jointly initiated research into this species of wedgefish by commissioning J.H.C. von Eitzen, captain of a German merchant ship and a drag net expert, to fish the estuary of the Cameroon River for months and to preserve the fishes caught according to precise instructions and to transfer them to Hamburg.

Hans Lübbert (1870–1951)

Lübbert and Ehrenbaum were well-regarded, both nationally and internationally, in various areas of fisheries and oceanography. But their reputations came to an end with the seizure of power by National Socialists (Nazis) beginning in 1933. Since Lübbert and Ehrenbaum came from Jewish families, they were targeted by Nazi officials. It did not matter that their parents had converted to Christianity. In fact, Ehrenbaum (nee Oppenheim) took the name of his stepfather, Major General Eduard Lübbert, a Prussian professional officer, after the death of his biological father and the remarriage of his mother. Because of their Jewish heritage they lost their jobs and their reputations were erased, at first slowly and embellished later with open hostility. For example, at first it was officially said that Ehrenbaum and Lübbert had simply retired when in fact they were forced to resign from their offices. The “official” Nazi explanation for their “retirements” can still be found in German biographical reviews today.