NAMES OF THE WEEK from: 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2022 2023 2024 2025

29 December

29 December

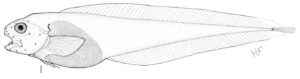

Lagodon rhomboides (Linnaeus 1766)

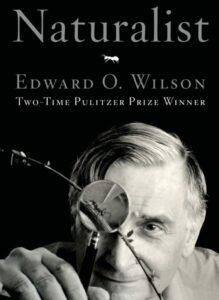

Edward O. Wilson, the Harvard biologist and two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning author who conducted pioneering work on biodiversity, insects and human nature, died on Sunday, Dec. 26, at the age of 92. While his specialty was myrmecology, the study of ants, it was a fish that, in his words, “determined what kind of naturalist I would eventually become.”

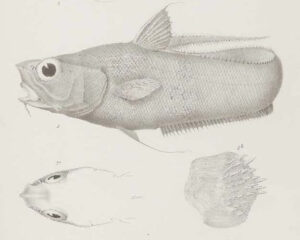

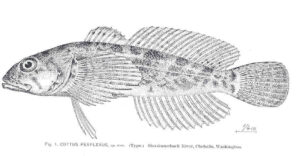

At the age of seven, Wilson spent the summer on the coast of the Florida panhandle. “I was fishing on the dock with minnow hooks and rod,” he wrote in his 1994 autobiography Naturalist, “jerking pinfish out of the water as soon as they struck the bait. The species, Lagodon rhomboides, is small, perchlike, and voracious. It carries ten needlelike spines that stick straight up in the membrane of the dorsal fin when it is threatened. I carelessly yanked too hard when one of the fish pulled on my line. It flew out of the water and into my face. One of its spines pierced the pupil of my right eye.”

The eye never healed and clouded over with a cataract. The young Wilson endured a painful surgery — a “terrifying nineteenth century ordeal,” as he described it — to remove the lens, leaving him blind in that eye. Later, during his adolescence, he lost most of his hearing in the upper registers (due apparently to a hereditary defect, not an accident). Unable to hear birds and frogs, but with exceptional short-range acuity in his surviving eye, Wilson turned his fascination toward insects, the “little things in the worlds,” he wrote, “the animals that can be picked up between thumb and forefinger and brought closer to inspection.”

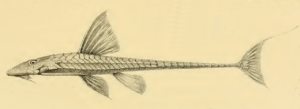

Lagodon rhomboides. Courtesy: ncfishes.com

The Pinfish Lagodon rhomboides, is a common member of the porgie or sea bream family Sparidae. It occurs in marine waters along the U.S. coast from Massachusetts to Texas, down along the Gulf Coast of Mexico, as well as Bermuda and some northern Caribbean islands. Linnaeus, the father of taxonomy, named it Sparus rhomboides in 1766, based on an illustration provided by Mark Catesby (1683-1749), one of the first naturalists to explore the New World. We believe the specific epithet rhomboides refers to the rhomboidal shape of the fish’s scales as illustrated by Catesby.

In 1855, American physician-naturalist John E. Holbrook (1796-1871) proposed Lagodon, a new genus for Sparus rhomboides. The name translates as lagos, Greek for hare or rabbit, and odon, Greek for tooth. We surmise that it refers to the eight broad, deeply notched incisor-like anterior teeth on both jaws.

If you’ve never read any of Wilson’s books, we highly recommend the following:

The Diversity of Life (1992)

Naturalist (1994)

Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge (1998)

The Future of Life (2001)

We regret not having read his Pulitzer Prize-winning magnum opus (written with Bert Hölldobler) The Ants. Unfortunately, the book has not been reprinted and used copies start at $141.37 on Amazon.

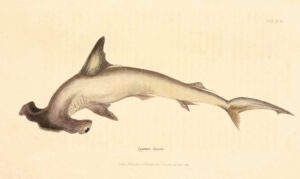

Zygaena (now Sphyrna) lewini. Illustrated by John William Lewin. From: Griffith, E. and C. H. Smith. 1834. The class Pisces, arranged by the Baron Cuvier, with supplementary additions. In: Cuvier, G: The animal kingdom, arranged in conformity with its organization. Vol. 10. Pisces. Whittaker & Co., London. 1-680, Pls. 1-62 + 3. [English treatment of Cuvier’s “Régne Animal”; supplements by Griffith and Smith.]

Sphyrna lewini (Griffith & Smith 1834)

In 2012, shark taxonomist David A. Ebert published a review of Jose I. Castro’s 2011 book The Sharks of North America in the journal Copeia (2012, No. 4, 765–778). It’s one of the most scathing reviews we’ve seen of a major ichthyological tome from a well-regarded specialist published by a major university press (Oxford). Ebert wrote:

“A major problem with the book is that the author frequently inserts his own opinion as fact and these opinions are often at odds with the published literature. He provides no supporting evidence while dismissing, or not even citing, the research of many contemporary researchers.”

The same can be said of Castro’s explanation of the etymology of the trivial name of the Scalloped Hammerhead Shark Sphyrna lewini, described by Griffith & Smith as Zygaena lewini

in 1834. Castro says the shark was “presumably” named in honor of Ludwig Lewin Jacobson (1783–1843), a “brilliant Danish military surgeon and one of the foremost anatomists of his age, a time when the nascent comparative anatomy under Georges Cuvier was the main basis for the study of biology.” Castro mentions that Jacobson discovered “what is now known as the vomeronasal organ of Jacobson, an accessory organ of many tetrapods. Cuvier published a description of this organ in 1811.” (Note: the organ does not occur in sharks.)

Castro did not explain how Jacobson was associated with Griffith & Smith nor why he was honored. (Or why Griffith & Smith chose his middle name over his surname.) In fact, when you read the Wikipedia entry for Jacobson, it seems he has no connection with sharks or sea-life whatsoever. Demonstrating Ebert’s major complaint about the book, Castro did not present any supporting evidence for his claim. Probably because there is no supporting evidence for his claim. There is, however, substantial evidence pointing to someone else.

Griffith & Smith did not identify the Lewin of lewini. They provide only a brief one-sentence description in the main text of the work. The name itself, Zygaena lewini, appears only on the accompanying plate (shown here). But Griffith & Smith did provide a tantalizing clue. They named another species after Lewin, Esox lewini, now known as Dinolestes lewini, the Long-finned Pike, a barracuda-like schooling fish from the coastal waters of Australia. Griffith & Smith described the fish “from a drawing by Mr. Lewin, made in New Holland [Australia], of a species not hitherto noticed.”

We believe “Mr. Lewin” is John William Lewin (1770–1819), an English-born artist who moved to Australia and illustrated early volumes of Australian natural history. (Sphyrna lewini was described from Australia.) This is almost certainly the same artist who illustrated the plates in Griffith and Smith’s book. Two birds are named after Lewin, Lewin’s Rail Lewinia pectoralis and Lewin’s Honeyeater Meliphaga lewinii. And, we are confident, two fishes as well.

The generic name Sphyrna, by the way, coined by Rafinesque in 1810, is probably a misspelling of sphyra, Greek for hammer, referring to their hammer-shaped heads.

15 December

Wool cards and fishes

This week’s entry continues the theme of last week’s — how tools and technology common to the 18th and 19th centuries are evoked in the names of several fishes described in those times. This week we look another tool. Wool cards.

I confess to never having heard of a wool card until I encountered one in the name of a fish. I blame the fact that I grew up in a major American city in the latter half of the 20th century and not on a farm during what we called the “olden days.” For those of you like me, a wool card is any kind of device with bristles used for separating and straightening sheep’s wool so that it can be used to make yarn for knitting. The process is now largely mechanical, but in the “olden days” people would card wool using a hand comb, similar to the kind of comb pet owners now used to groom their pets. The word “card” is derived from the Latin carduus, meaning thistle or teasel, as dried vegetable teasels were first used to comb the wool. Bristles made of wire now do the job.

Based on how wool cards have been evoked several in the names of fishes, I surmise that they were a common, everyday device in earlier times — common enough for four ichthyologists to examine a fish and exclaim, “Dang, that fish reminds me of a wool card!” In fact, our friend Holger Funk tells us that the fish-card connection dates to at least the Renaissance. In his Aquatilium animalium historiae liber primus of 1558, Hippolito Salviani (1514-1572) compared the dainty teeth of the European Bass Dicentrarchus labrax to wool cards. (The technical term for this arrangement is now known as “cardiform.”)

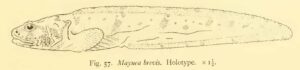

In 1858, French-American ichthyologist Charles Girard (1822-1895) described a new genus of fishes from the Pacific Ocean of North America. He named it Zaniolepis, from xanion, wool card, and lepis, Greek for scale, referring to the imbricated, extremely roughly ctenoid scales of Z. latipinnis, or, to use Girard’s words, “Dermic productions comb-like.” In a follow-up paper published later in 1858, Girard described “prickles of the skin … in the shape of comb-like scales.” The family Zaniolepididae, with just two species, is colloquially called Combfishes.

Thirty years later, zoologist Léon Vaillant (1834-1914) of the Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle in Paris, described a new species of grenadier from the coast of Western Sahara. He named it Macrurus (now Coryphaenoides) zaniophorus, i.e., comb-bearer, using the same Greek noun that Girard chose for Zaniolepis. Larger specimens have short, stout spinules on their scales arranged in V-shaped rows, resembling the wire bristles of wool cards.

Coryphaenoides carminifer. ote the wool card-like spines on the scale. From: Garman, S. 1899. The Fishes. In: Reports on an exploration off the west coasts of Mexico, Central and South America, and off the Galapagos Islands … by the U. S. Fish Commission steamer “Albatross,” during 1891. No. XXVI. Memoirs of the Museum of Comparative Zoology v. 24: Text: 1-431, Atlas: Pls. 1-85 + A-N.

The noun xanion was used again by American ichthyologist Charles Henry Gilbert (1859-1928) when he described Catulus (now Parmaturus) xaniurus, a deepwater catshark from the eastern Pacific, in 1892. Oura is Greek for tail. The name refers to the crest-like row of tooth-like projections along the upper edge of its caudal fin.

For a southeastern Pacific congener of Coryphaenoides zaniophorus, Harvard ichthyologist-herpetologist Samuel Garman (1843-1927) chose the same name, except in Latin instead of Greek — carminifer (carmen, wool card + fero, to bear) — described in 1899. The name refers to the longitudinal series of spines on each scale, which give the fish a “pilose grayish brown appearance.”

Do you think any contemporary ichthyologists will name a fish after a tool that’s common today? A smartphone, perhaps? A drone? Photovoltaic cells?

8 December

Saddles, bridles and whips

Some fish names reflect the times in which they were described. In the 18th and 19th centuries, horses were the primary mode of transportation. Which may explain why horses are evoked so many times in the names of fishes described before the advent of “horseless carriages.”

Riding horses need saddles, of course. Ephippion is Greek for saddle. It Latin it’s sella. We count eight currently valid fish species from the 1700s and 1800s named for their saddle-like markings:

- Amphiprion ephippium (Bloch 1790), an anemonefish

- Chaetodon ephippium Cuvier 1831, a butterflyfish

- Thorogobius ephippiatus (Lowe 1839), a goby

- Stigmatogobius sella (Steindachner 1881), a mudskipper goby

- Apogon retrosella (Gill 1862), a cardinalfish (retro = back)

- Dascyllus albisella Gill 1862, a damselfish (albus = white)

- Microcottus sellaris (Gilbert 1896), a sculpin

- Argyripnus ephippiatus Gilbert & Cramer 1897, a bristlemouth

Riding horses also need bridles (frenum, Latin noun; frenatus, Latin adjective, i.e., bridled). These 18 fishes were all named for the bridle-like markings on the sides of their heads.

- Scarus frenatus Lacepède 1802, a parrotfish

- Sufflamen fraenatum (Latreille 1804), a triggerfish

- Scolopsis frenata (Cuvier 1830), a threadfin bream

- Pristiapogon fraenatus (Valenciennes 1832), a cardinalfish

- Sparisoma aurofrenatum (Valenciennes 1840), a parrotfish (auro = gold)

- Oxynoemacheilus frenatus (Heckel 1843), a stone loach

- Paramonacanthus frenatus (Peters 1855), a filefish

- Amphiprion frenatus Brevoort 1856, an anemonefish

- Crenicichla frenata Gill 1858, a pike cichlid

- Rypticus subbifrenatus Gill 1861, a soapfish (sub = somewhat; bi = two)

- Brachyistius frenatus Gill 1862, a surfperch

- Stegastes rectifraenum (Gill 1862), a damselfish (rectis = straight)

- Coryphopterus glaucofraenum Gill 1863, a goby (glaucus = hoary blue)

- Arenigobius bifrenatus (Kner 1865), a goby (bi = two)

- Notropis bifrenatus (Cope 1867), a shiner or minnow (bi = two)

- Gymnocranius frenatus Bleeker 1873, a large-eye seabream

- Zaniolepis frenata Eigenmann & Eigenmann 1889, a combfish

- Sarritor frenatus (Gilbert 1896), a cardinalfish

Dules auriga, named for the long, whip-like third spine of its dorsal fin. From: Cuvier, G. and A. Valenciennes. 1829. Histoire naturelle des poissons. Tome troisième. Suite du Livre troisième. Des percoïdes à dorsale unique à sept rayons branchiaux et à dents en velours ou en cardes. F. G. Levrault, Paris. v. 3: i-xxviii + 2 pp. + 1-500, Pls. 41-71.

We can imagine that some 18th- and 19th-century zoologists, at least those who could afford it, commuted between museum and home via a horse-drawn carriage. That may explain these five fishes, all of which have filamentous or whip-like fins, were named auriga, the Latin word for driver or charioteer, i.e., a coachman or carriage driver, who drives and “encourages” his horse with the help of a whip.

- Chaetodon auriga Forsskål 1775, a butterflyfish

- Dules auriga Cuvier 1829, a sea bass or grouper

- Pagrus auriga Valenciennes 1843, a porgie or seabream

- Pteragogus aurigarius (Richardson 1845), a wrasse

- Trichiurus auriga Klunzinger 1884, a cutlassfish

Interestingly, we haven’t found any modern-day fish names that evoke fenders, grills and steering wheels. What do you make of that?

1 December

Universal Human Rights Month

Today, December 1, is the beginning of Universal Human Rights Month, a time for people around the world to join together and stand up for the rights and dignity of all individuals.

Human rights are evoked in the names of three fishes:

Dicrossus foirni Römer, Hahn & Vergara 2010 — This cichlid occurs in the Rio Negro drainage of Brazil. It is named in honor of FOIRN, Federação das Organizações Indígenas do Rio Negro, a non-governmental organization that has repeatedly given scientists permission to travel on the tribal land of the village communities of different indigenous groups in the middle and upper Rio Negro and its affluent rivers, permitting the observation and collection of this species and D. warzeli (described at the same time). According to the authors, the “name is also intended to highlight the fact that the basic human rights of indigenous peoples, who depend on large functional ecosystems for all necessary resources, are still in question in most parts of Amazonia when business projects (such as logging, mining, or the building of hydroelectric dams) are planned in the wilderness of the Neotropical rainforests.” FOIRN was founded to help indigenous peoples along the Rio Negro take over responsibilities and decision-making powers for their land and resources from local governmental organizations.

Lateral view of live Enteromius mandelai, showing live coloration of mature breeding (a) female, (b) male, and (c) female specimens. From: Kambikambi, M. J., W. T. Kadye and A. Chakona. 2021. Allopatric differentiation in the Enteromius anoplus complex in South Africa, with the revalidation of E. cernuus and E. oraniensis, and description of a new species, E. mandelai (Teleostei: Cyprinidae). Journal of Fish Biology v. 99 (no. 3): 931-954.

Etheostoma jimmycarter Layman & Mayden 2012 — This darter (Percidae), the Bluegrass Darter, is endemic to the Green River drainage of Kentucky and Tennessee. It is named in honor of Jimmy Carter (b. 1924), the 39th President of the United States of America, for his “environmental leadership and accomplishments in the areas of national energy policy and wilderness protection, and his life-long commitment to social justice and basic human rights.” (The name is a noun in apposition, without the patronymic “i.”)

Enteromius mandelai Kambikambi, Kadye & Chakona 2021 — The name of this recently described barb (Cyprinidae), the Eastern Cape Chubbyhead, honors Nelson Mandela (1918-2013), South Africa’s first democratically elected head of state, who was from the Eastern Cape Province where this species is endemic. The authors praise Mandela for his “legacy and selfless contribution towards promotion of peace, democracy, human rights, equality, social justice and sustainable development.”

Carcharhinus cautus. From: Whitley, G. P. 1945. New sharks and fishes from Western Australia. Part 2. Australian Zoologist v. 11 (pt 1): 1-42, Pl. 1.

24 November

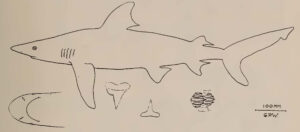

The Nervous Shark, Carcharhinus cautus

For most people, “nervous” is not an adjective they would normally associate with sharks. Aggressive, yes. Mean. Scary. Dangerous. Adjectives like that. But nervous? No, not really. Yet that’s the adjective ichthyologist Gilbert Whitley used when he described Carcharhinus cautus, an Indo-Pacific shark, in 1945.

Actually, Whitley did not explicitly explain the name in his 1945 description. But he mentioned that Carcharhinus cautus is the same shark he called the “Nervous Shark” in his 1940 book The fishes of Australia. Part I. The sharks, rays, devil-fish, and other primitive fishes of Australia and New Zealand. We googled the title and were able to secure a second-hand copy at a reasonable price. Whitley wrote:

When at Shark’s Bay, Western Australia, I sometimes saw small black Galeoid sharks in shallow water but never could approach them closely since the slightest splashing caused them to dash away at great speed into deep water. Some teeth, perhaps of this species, were given to me by Mr. C. Fletcher of Willamia, Unless Inlet, and agree with no other Australian species.

Whitley eventually captured one of these Nervous Sharks, from Herald Bight, Shark Bay, in Western Australia. “Many specimens were swimming about at the time,” he wrote, “but though my companions and I tried to wade near them, we were unable to get close and only managed to net one of the school.” It was an immature female, about a meter long and 5 kg in weight.

Whitley described the shark as a subspecies of Galeolamna greyi (now a junior synonym of the Dusky Shark Carcharhinus obscurus). The subspecies has since been recognized as a full species and moved to the genus Carcharhinus.

“Cautus” is Latin for nervous, cautious or wary.

Walleye (Sander vitreus) from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

17 November

Stizostedion vs. Sander

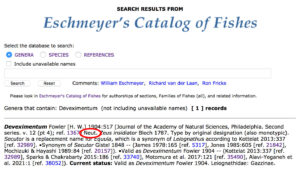

When I read John C. Bruner’s essay In the June 2021 issue of Fisheries magazine, I knew something was not quite right. Bruner argued that Stizostedion Rafinesque 1820 should replace Sander Oken 1817 as the proper generic name for Walleye, Sauger and European pikeperches. If Bruner was correct, then his argument would apply and perhaps necessitate the changing of 14 other currently valid generic names dating to Oken 1817. I sent Bruner’s essay to ichthyologist Ronald Fricke, one of the editors of Eschmeyer’s Catalog of Fishes, and he agreed something was amiss. As we reexamined Bruner’s evidence, Dr. Fricke and I concluded that Sander should be retained. We collaborated on a rebuttal essay, which Fisheries magazine recently published online (and will likely appear in print early next year).

The Stizostedion vs. Sander debate has been around since 1903. Rafinesque proposed Stizostedion (stizo, prick; stithios, a little breast, referring to “pungent throat” or spiny opercle at pectoral-fin base of S. vitreus) in 1820. In 1903, Theodore Gill revealed that Sander Oken 1817 (based on Cuvier’s “Les Sandres,” from zander, German name for S. lucioperca) predates Stizostedion and should replace it. Gill’s paper was largely ignored until European and Russian ichthyologists started using Sander in the 1990s. This prompted the Committee on Names of Fishes, a joint committee of the American Fisheries Society and American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists, to examine the issue. In 2003, they recommended that Sander replace Stizostedion. This change, a significant one considering the commercial importance of Walleye and Sauger, has been adopted by nearly every academic and popular publication ever since.

Bruner rejected Sander in favor of Stizostedion on the grounds that Gill incorrectly treated Oken’s Sander as a properly erected generic name. According to Bruner, Oken did not latinize “Sander” (e.g., Sandrus) nor differentiate the genus and designate a type species, all required actions, Bruner implied, for making a genus-level name available. We counter-argued that Sander is an acceptably formed and published scientific name consistent with standards predating the International Commission of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN). Indeed, our main concern with Bruner’s arguments is that they apply modern-day nomenclatural guidelines to a taxon proposed in the early days of binominal zoological nomenclature, decades before the publication of the first edition of the ICZN code in 1905. Simply put, Oken’s Sander, while it would not pass nomenclatural muster today, is “grandfathered” in. So too are 14 other currently valid names proposed by Oken: Atropus, Brosme, Cirrhinus, Diagramma, Lota, Piabucus, Plectropomus, Polyprion, Priacanthus, Pterois, Raniceps, Schilbe, Stellifer, and Triacanthus. Should we throw them out as well?

I could spell out our arguments in more detail, but then there would be no need to read the essay, which is available here. (If you can’t get past the paywall, click on my email and I’ll send you a copy.) Bruner’s essay is freely available here.

You be the judge!

An adult male Danionella cerebrum, ca. 10 mm SL. From: Britz, R., K. W. Conway and L. Rüber. 2021. The emerging vertebrate model species for neurophysiological studies is Danionella cerebrum, new species (Teleostei: Cyprinidae). Scientific Reports v. 11: 18942: 1-11.

10 November

Danionella cerebrum Britz, Conway & Rüber 2021

A handful of fishes are named for their importance to humans. Among them are the American Shad, Alosa sapidissima, whose name means “most delicious,” and the tilapiine cichlid Oreochromis esculentus, meaning edible, referring to its former importance for human sustenance along Africa’s Lake Victoria (the species is now critically endangered). To this rather small list of fish names we can add an extremely small new species, Danionella cerebrum, named for its value not on the dinner plate but in the lab.

Maturing at just 10–15 mm in length, the genus Danionella from Myanmar and northeastern India are among the smallest vertebrates in the world. The fifth and most recently described species has “brainy” name — cerebrum.

Danionella cerebrum is known from a number of streams on the southern and eastern slopes of the Bago Yoma mountain range of Myanmar. Its name, Latin for brain, refers to the fact that it has one of the smallest adult brains among vertebrates, thereby making it a promising new model species for neurophysiological studies. One of the striking morphological features of the larval-like Danionella is that the roof of their skull is missing. Instead, it’s covered by skin, which allows researchers to study neurophysiological questions by deep imaging the fish’s brain activity while the fish is still alive.

Having a tiny, larval-like brain, the authors write, makes Danionella cerebrum a “promising new model species” for neuroscientists interested in learning more about brain activity and function.

Zeus faber. Courtesy: Wikipedia.

3 November

Zeus faber Linnaeus 1758

Names that date to antiquity are often hard to figure out. These names appear in classical texts with little or no context, their original meanings vague or unknown. Over the centuries, an ancient name may be applied to several different species, further complicating its history. Its spelling may be changed as it’s translated between Latin and Greek and eventually into German, French or English. By the time the likes of Artedi and Linnaeus affix the name to the fish by which it is known today, its original meaning, spelling and application may be long gone. And when more contemporary scholars make unsubstantiated claims about its provenance, the etymological waters are muddied even more. Both parts of the name of the John Dory — the generic name Zeus and the specific name faber — have deep, tangled histories that we are just beginning to decipher.

Let’s start with the specific epithet faber, which is the easier of the two names to pin down. We know that “faber” is the Latin word for craftsman, carpenter or workman, but we had no idea how that word could apply to this fish. So, we published all that we knew: Faber is “ancient name for this species, dating to at least ‘Halieutica’ (‘On Fishing’), a fragmentary didactic poem spuriously attributed to Ovid, circa AD 17.”

Then we met Holger Funk, a scholar of Greek and Latin who is researching the emergence of modern ichthyology in the 16th century. He has traced “faber” to a 1533 work by French naturalist, topographer and translator Pierre Gilles (aka Petrus Gyllius), De gallicis et latinis nominibus piscium (The French and Latin names of fishes). Gilles said people from Dalmatia (a region on the eastern shore of the Adriatic Sea, now part of Croatia) called the fish “faber,” meaning craftsman, referring to how “all the tools can be found in it” (translation). Hippolito Salviani, in his Aquatilium Animalium Historiae (1558), repeated and embellished Gilles’ claim, adding that the fish’s dorsal-, ventral- and anal-fin spines, and its head bones, resemble the tools of a craftsman. Whether this name traces back to “Halieutica” is impossible to say. But at least we have a viable explanation as to why ancient scholars and writers applied the noun “faber” to this fish.

The meaning of Zeus is a tougher and perhaps impossible knot to untie. This is what we had posted: “the Greek god Zeus, equivalent to the Roman god Jove or Jupiter, referring to the ancient name of Z. faber, ‘Piscis Jovii.’”

The source of this explanation is a 1902 article by David Starr Jordan, the dean of American ichthyology (“The History of Ichthyology,” Science, v. 16 [no. 398]: 241-258). Jordan’s explanation has been repeated in many references, including ETYFish. According to Dr. Funk, it’s total rubbish. Jordan provided no evidence for claim, and Funk has never seen “Piscis Jovii” mentioned in any classical lexicon. A Google search supports this notion. The #2 hit is Jordan’s article.

So, if Jordan’s “Piscis Jovii” is rubbish, then where did the name “Zeus” come from? It’s true, zeus, like faber, was an ancient name for the John Dory. Pliny mentions this in his Natural History (Book IX, Chap. 32). But Pliny spelled the name as Zaeus (from the Greek Ζαιός),

According to Dr. Funk, zaeus and zeus are not necessarily the same word. Nowadays, “zaeus” is speculatively associated with ζαιός (stormy, windy), which doesn’t seem to apply to this fish. What’s more, there is no record that the Greeks and Romans used the “zeus” spelling. In fact, in classical Latin, Zeus, the god, is almost always referred to as Iupiter or Iuppiter. The “zeus” spelling for the fish was adopted by Renaissance naturalists and then codified by Artedi and Linnaeus, who, in Funk’s words, “made the nonsense official.” The “Zeus” of Zeus faber may have nothing to do with the chief Greek deity. It may simply have been a Greek word for the fish whose meaning, if any, has been lost to time.

Our thanks to Holger Funk for sharing his research and philological expertise.

Kajikia mitsukurii (=audax). From: Hirasaka, K. and H. Nakamura. 1947. On the Formosan spear-fishes. Bulletin of the Oceanographic Institute Taiwan No. 3: 9-24, Pls. 1-3.

27 October

Kajikia Hirasaka & Nakamura 1947 is now Kajikia Marshall & Palmer 1950

Article 13.3 of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature strikes again! This time the subject is not some obscure group of fishes known only to ichthyologists. It’s the genus Kajikia, which contains two of the most prized sportfishes in the world, the White Marlin K. albida, and the Striped Marlin, K. audax.

According to Article 13.3, every new genus-group name published after 1930 must be accompanied by the fixation of a type species in the original publication (or be expressly proposed as a new replacement name) in order to be available. If not, then the genus is not considered validly described until someone indicates a type – sometimes when the genus is mentioned in the Zoological Record (ZR), the unofficial registry of scientific names in zoology. In these cases, the author(s) of the ZR entry are not intending to designate the type. Usually, they’re just assuming the first-mentioned species is the type and record it as such. But in so doing, they inadvertently became the “author” of the name even though they had nothing to do with studying the genus, examining the specimens, and proposing the name in question.

This is precisely what happened with Kajikia, proposed by Japanese ichthyologists Kysoke Hirasaka and Hiroshi Nakamura in their 1947 paper “On the Formosan Spear-Fishes.” They included two species in the genus, K. formosana and K. mitsukurii, both now considered junior synonyms of K. audax (Philippi 1887). Unfortunately, they did not indicate which of the two species should be the representative “type” of the genus. Three years later, when the Zoological Record for 1947 was published, K. formosana was indicated as the type. The authors of the fish section, Marshall & Palmer, thus inadvertently became the authors of the genus.

Art. 13.3 is a quirky rule, but the fixation of types is an important concept in taxonomy. Every genus should have a single species that provides the objective standard of reference by which that genus is differentiated from closely related genera. Since Hirasaka & Nakamura did not mention which of their two species of Kajikia provided that objective standard, authorship of the genus is credited to those who did. Our guess is that Hirasaka & Nakamura simply did not know about Art. 13.3. It may have been added when the Code was amended in 1930, the news of which probably did not make its way to post-war Japan.

In the course of our etymological research, we’ve found two instances in which Art. 13.3 needed to be applied: the sculpin genera Artediellichthys (NOTW 23 June 2021) and Leocottus (NOTW 15 Sept. 2021). We also found one instance in which Art. 13.3 was erroneously applied: the barrucudina genus Macroparalepis (NOTW 18 May 2016).

What does kajikia mean? It’s derived from kajiki, the Japanese word for marlin or sailfish.

Percina nevisensis. Courtesy: ncfishes.com

20 October

Percina nevisensis (not nevisense)

The Chainback Darter (Percidae) occurs in gravel runs and riffles of small to medium-sized rivers from the Roanoke-Chowan River drainage of Virginia south to the Neuse River drainage of North Carolina in the eastern United States. Nearly every contemporary reference gives its scientific name as Percina nevisense. When we took a closer look at the etymology of “nevisense,” however, we discovered that it should be spelled “nevisensis.” Here’s why:

Edward Drinker Cope described this species as Etheostoma nevisense in 1870. As was his custom, he did not explain the meaning of its name. Near the beginning of the 20th century, American ichthyologists began treating the species as a junior synonym of the Shield Darter, Percina peltata. In the 1980s, “darterologists” considered it a subspecies of P. peltata. In 1998, the taxon returned to full species status. During all these taxonomic maneuverings, no one bothered to look at the spelling of its name, perhaps because a major reference explained what it meant. In the 1983 book American Darters, authors Kuehne and Barber stated that “nevisense” means “birthmark,” probably referring to its blotches, which Cope described as “dark chestnut quadrate spots” on sides.

According to our dictionaries, “naevus” is the Latin noun for birthmark. We’re not sure how Keuhne and Barber saw “naevus” in “nevisense.”

We’re also not sure how Kuehne and Barber missed a more obvious, and therefore more likely, explanation of the name.

Animals named after places often have the adjectival suffix “-ensis” in their specific names. For masculine and feminine genera, “-ensis” is the correct spelling. For neuter names, the correct spelling is “-ense.” Note that Cope originally described the darter in the genus Etheostoma. The gender of Etheostoma is neuter. So, if Cope named the darter after a place, “nevisense” — not “nevisensis” — would have been the proper spelling based on its placement in Etheostoma.

But what place was Cope referring to? We’re not 100% sure but we have a very good guess. Cope described the species from one specimen from the Neuse River in Wake County, North Carolina. Since Cope was classically trained (as were most scientists of the time), he probably latinized the “u” of Neuse to “v” (in Classical Latin the “v” shape was used for both the vowel “u” and the consonant “v”). The addition of the “i” is harder to explain. Cope may have added it for euphony (“nevisense” is slightly better-sounding than “nevsense”). Or perhaps it is a typographical error. In those pre-digital (and pre-typewriter) days, handwritten manuscripts were often rife with errors, and hand-set galleys were not usually sent to reviewers and proofreaders before publication as they are today.

Long story short: “From the Neuse River” is a more likely explanation than “birthmark.” Since Percina is a feminine genus — and if you accept the notion that the specific epithet is an adjective, not a noun — then the spelling of “nevisense” should be emended to “nevisensis.”

Cylix tupareomanaia at Waiatapaua Bay, Whangaruru, Northland, New Zealand, 12 m depth. © Irene Middleton, from an Auckland Museum press release. Also appeared in: Short, G. A. and T. Trnski. 2021. A new genus and species of Pygmy Pipehorse from Taitokerau Northland, Aotearoa New Zealand, with a redescription of Acentronura Kaup, 1853 and Idiotropiscis Whitley, 1947 (Teleostei, Syngnathidae). Ichthyology & Herpetology 109 (3): 806-835.

13 October

Cylix tupareomanaia Short, Trnski & Ngātiwai 2021

As far as we know, this is the first animal in the world to have its naming authority, or authorship, include not just the name of a person but that of an entire tribe.

Cylix tupareomanaia is both a new genus and species of pygmy pipehorse — 6 cm long — from rocky reefs off the northeast coast of New Zealand. It was discovered by divers in 2011, who initially identified it as a Collared Seahorse, Hippocampus jugumus. When photos circulated on the Internet in 2017, ichthyologist Graham A. Short (California Academy of Sciences) recognized it as a potentially new species. Thomas Trnski (Tāmaki Paenga Hira Auckland Museum) joined Short to hand-collect specimens and prepare a formal description.

Short and Trnski are credited as the authors of the generic name Cylix. It’s derived from the Greek kylix, meaning cup or chalice, referring to the cup-like pentamerous crest on top of the pipehorse’s head. For the specific epithet, Short and Trnski conferred with kaumātua (tribal elders) of Ngātiwai (a local Māori iwi, or tribe), to incorporate mātauranga (Māori knowledge) into the naming process. The kaumatua “gifted” (the verb used in the description’s etymology section) the name tupareomanaia, a neologism comprised of two indigenous names:

tupareo — from Tu Pare o Huia, “plume of the huia,” Ngātiwai name for Home Point, adjacent to the type locality, itself a combination of pare, plume or garland, and huia, an extinct bird, referring to the pipehorse’s head crest

Manaia — Māori name for a seahorse (also an ancestor that appears as a stylized figure used in Māori carvings representing a guardian)

The name of the Ngātiwai tribe — not a single person in the tribe but the entire tribe itself — is credited with co-authorship of the name: Short, Trnski & Ngātiwai 2021.

Ngātiwai kaumātua Hori Parata said, “The naming of this taonga [treasure] is significant to Ngātiwai as we know there are stories from our tupuna [ancestors] about this species, but the original name has been lost as a result of the negative impacts of colonisation.”

Ngātiwai are kaitiaki (guardians) of the biodiversity within their rohe (territory), and they regard the marine species as nationally significant taonga (treasures).

Type specimens of Polymixia hollisterae. From: Grande, T. C. and M. V. H. Wilson 2021. A new cryptic species of Polymixia (Teleostei, Acanthomorpha, Polymixiiformes, Polymixiidae) revealed by molecules and morphology. Ichthyology & Herpetology 109 (2): 567-586.

6 October

Polymixia hollisterae Grande & Wilson 2021

The person for whom this species is named was such a trailblazer, the authors appended their description with a short biographical essay, which we summarize below.

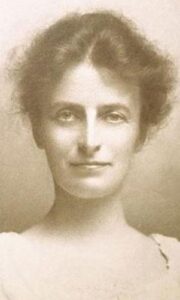

The Bermuda Beardfish Polymixia hollisterae is a new species known from only three specimens, two collected along the northwest edge of the Bermuda Platform in the western Atlantic, and one (a juvenile) collected in the Gulf of Mexico. Its specific name honor Gloria E. Hollister (married name Anable), B.S., M.S. (1900–1988). In the etymology section, the authors describe her as a “pioneering ichthyologist, key member of the William Beebe bathysphere expeditions in Bermuda, world record holder for deep-sea descent by a woman, leader of tropical zoological expedition, Red Cross Blood Bank pioneer, and ground breaking conservationist.” The authors then direct us to Appendix 1 for more about her accomplishments.

Gloria Hollister graduated with a degree in zoology from Connecticut College (B.S. 1924) and a master’s from Columbia University (M.S. 1925). During this time, she participated in an expedition to British Guiana, where, records suggest, she met William Beebe (1877–1962) for the first time. Beebe, a naturalist and explorer working for the New York Zoological Society (now the Wildlife Conservation Society), would soon be famous for his deep-sea dives aboard the Bathysphere, a spherical deep-sea submersible, and his best-selling account of these dives, Half-Mile Down. His dives marked the first time that a marine biologist observed deep-sea animals in their native environment.

Hollister was a key member of Beebe’s team during his deep-sea Bathysphere explorations in the waters off Bermuda from 1928 to 1940. Her main responsibilities were surface-to- Bathysphere communication and the recording of the conversations to and from the submersible, and identifying the fishes Beebe saw. She also descended in the Bathysphere herself, setting records for depth of descent by a woman — 410 feet (125 m) in 1930 and 1,208 feet (368 m) in 1934 — the latter a record that stood for decades.

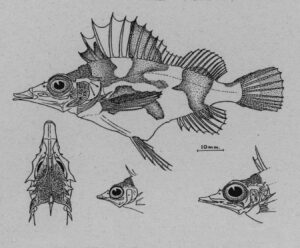

Gloria Hollister and her “Fish Magic.”

Working in the team’s laboratory on Nonsuch Island in Bermuda, Hollister perfected and published the first reliable method of clearing and staining fishes for study of their osteology. She called the results ‘‘Fish Magic.’’

In 1941, Hollister joined the American Red Cross to help organize its first blood donor project; the blood was badly needed because of World War II. She eventually became the public face of the Red Cross and blood donation. At around this time she married Anthony Anable, a chemical and metallurgical engineer.

After the end of the war, Hollister led a citizens’ effort to save from imminent destruction the Mianus River Gorge near the New York-Connecticut border. Working with The Nature Conservancy, Hollister and other like-minded conservationists, they purchased the Gorge, which became the first ever land purchase project of The Nature Conservancy, and later became the first National Natural Landmark to be officially registered in the U.S.

According to Wikipedia, Hollister spent the last three years of her life at a convalescent hospital in Fairfield, Connecticut. She died of cardiac arrest on February 19, 1988, at the age of 87.

The etymology of the generic name Polymixia is also worth noting. Proposed by British biologist-clergyman Richard Thomas Lowe (1802-1874) in 1836, the name is a combination of poly, many, and myxia, mixing, referring to how the type species, P. nobilis, appears to combine characters from multiple groups of fishes (e.g., the general aspect of Berycidae, the chin barbels of Mullidae). The name has proven to be prophetic. The genus, now with 11 species, has defied easy placement in fish classifications, jumping from one order to the next depending on the study. It currently sits in its own order, Polymixiiformes, phylogenetically positioned at or near the base of the Paracanthopterygii, a group that also includes the orders Percopsiformes, Zeiformes, Stylephoriformes, and Gadiformes.

According to one ichthyologist, “If there is an acanthomorph equivalent of the living monotremes [platypus and echidnas] amongst mammals, it is Polymixia …”

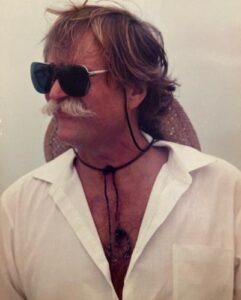

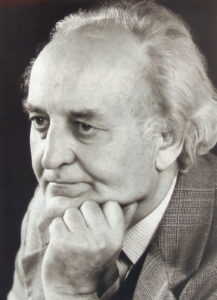

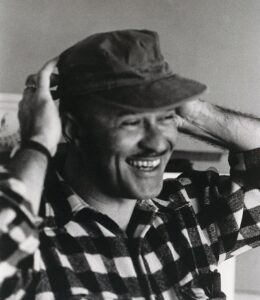

John “Jack” Musick, from his obituary at Legacy.com.

29 September

Stellifer musicki Chao, Carvalho-Filho & Andrade Santos 2021

John Andrew Musick, known to all as Jack, passed away at home in Gloucester, Virginia, on February 13, 2021, at the age of 80. He was the Marshall Acuff Professor of Marine Science Emeritus at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science, College of William and Mary, where he taught ichthyology, conservation biology, deep sea biology, biological oceanography, and marine fisheries science from 1968 until his retirement in 2009.

Jack was senior author or coauthor of 170 scientific papers, served as coauthor and editor of 14 scientific books and proceedings, and coauthored eight trade books, four of them with his wife Beverly, a science writer. Their book The Shark Chronicles detailed Jack’s life and times studying sharks with other prominent researchers. He also co-authored Fishes of the Chesapeake Bay (Smithsonian Institution Press, 1997).

Born in Trenton, New Jersey, Jack spent his boyhood collecting snakes and other critters both large and small. After his father’s death when Jack was only 12, his mother marshalled uncles and friends to help nurture Jack’s blossoming interest in fishes, particularly the marine species that he could catch along the Jersey shore. An undergraduate degree from Rutgers University and a masters and Ph.D. from Harvard University led to a life of bliss — studying the marine creatures he loved so much, and mentoring students. All told Jack served as a Major Advisor to 38 master’s and 50 Ph.D. students.

Jack’s fascination with sharks drove much of his research. He was a founding member and early president of the American Elasmobranch Society. An ardent advocate for shark conservation, Jack was instrumental in convincing Congress to pass legislation regulating commercial shark fisheries along the eastern seaboard while supporting recreational fisheries. In the early 1970s he established what became the world’s longest time series of annual shark surveys, a tool that to this day continues to help with global shark management. This and other research led to Jack serving many years as co-chair of the Shark Specialist Group of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

In addition to sharks, Jack was an expert on sea turtles. He cofounded and served as president of the International Sea Turtle Society (ISTS) and helped pioneer the use of satellite tracking to better understand the biology and life history of leatherback and loggerhead sea turtles. For more than 25 years he served as Regional Coordinator for Virginia for the National Marine Fisheries Service Sea Turtle Stranding Network.

Stellifer musicki. From: Chao, N. L., A. Carvalho-Filho and J. de Andrade Santos. 2021. Five new species of Western Atlantic stardrums, Stellifer (Perciformes: Sciaenidae) with a key to Atlantic Stellifer species. Zootaxa 4991 (no. 3): 434-466.

When Jack passed away in February, we did not honor him in a “Name of the Week” because we could not link him to the name of a fish. He never named a new species, and no currently valid fish species is named after him. (Urophycis musicki Cohen & Lavenberg 1984, a phycid hake, is now treated as a junior synonym of Phycis blennoides.) But a recent paper in the journal Zootaxa has remedied this situation. In a June 2021 review of Western Atlantic stardrums of the genus Stellifer (Sciaenidae), a fish now bears Jack’s name:

Stellifer musicki is endemic to Brazil, south of Amazon River delta from Bragança, Pará, to Bahia. It can be distinguished from all other Atlantic species of the genus with a horizontal or inferior mouth by its large, oblique mouth and large eye (3.8–4.5 in HL). The etymology section reads: “This species is named in honor of the late Dr. Jack A. Musick, formerly at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science, College of William and Mary. Jack was the major professor of N.L. Chao [senior author of description] and many students, including several Brazilian ichthyologists.”

22 September

Four autumnal fishes

Autumn Darter, Etheostoma autumnale. © Joseph R. Tomelleri.

Today is the first day of autumn in the temperate Northern Hemisphere. In Latin, autumnus means a “season of increase and abundance,” referring to the ripening and harvest of fruits, vegetables and grains that grew over the summer. Four fishes have been named for autumn, two for their seasonal behavior and two for their colors, reminiscent of the leaves of deciduous trees as they prepare to shed.

Alosa braschnikowi autumnalis (Berg 1915) This subspecies of the Caspian Marine Shad is named for the fact that it is the only clupeid (or herring) that occurs in the southern Caspian Sea during September and October.

Coregonus autumnalis (Pallas 1776) The Arctic Cisco of Siberia, Alaska and Canada is named for how it migrates from the sea to fresh water in “immense numbers” (translation) during the autumn months of the year.

Badis autumnum Valdesalici & van der Voort 2015 Members of the family Badidae are called chameleonfishes for their ability to change colors to match their surroundings and suit their moods. Badis autumnum from West Bengal, India, is named for the numerous colors of autumn (combinations of brown, black, yellow and orange) it can display at any given time. We find it interesting that most of India does not experience the colorful seasonal makeover for which the fish is named. We suspect the authors — from Italy and Switzerland, respectively — are reflecting their geographic bias.

Etheostoma autumnale Mayden 2010 The Autumn Darter (Percidae) is named for its reddish-orange, orange, brown, tan, and reddish-yellow colors, typical of the seasonal autumn colors found in the Ozarkian hardwood forests of Missouri and Arkansas (USA), where it is endemic. The name also honors Frank B. Cross (1925–2001), Curator of Fishes, University of Kansas, a “great ichthyologist, naturalist, mentor, and friend” who was “adamant” that this darter not be named after him. So Mayden named it for “one of [Cross’] favorite seasons of the year.”

Dmitrii Nikolaevich Taliev at work in October 1946. Photo by D. G. Debabov. From: Taliev, D. N. 1955. Sculpin fishes of Lake Baikal (Cottoidei). Izdatel’stvo Akademii Nauk S.S.S.R., Moscow and Leningrad. 1-603, 2 foldout tables.

15 September

Leocottus Taliev 1955 is now Leocottus Palmer 1961

According to ICZN Art. 13.3, every new genus-group name published after 1930 must be accompanied by the fixation of a type species in the original publication (or be expressly proposed as a new replacement name) in order for that name to be available.

Dmitrii Nikolaevich Taliev (1908-1952) was a Soviet ichthyologist-limnologist known for his work studying the sculpins of Russia’s Lake Baikal. Three years after his death, his magnum opus, the 600+ page Sculpin Fishes of Lake Baikal (Cottoidei), was published. In it he proposed Leocottus, a subgenus of Paracottus with two included species and one subspecies. Unfortunately, he did not designate which species represents the type — i.e., the standard bearer or prototypical representative — of the subgenus (which Russian ichthyologists began treating as a full genus in 2001). Based on contextual clues, it appears that Taliev intended Paracottus (Leocottus) pelagicus, now a junior synonym of L. kesslerii (Dybowski 1874), to be the type. But since he did not explicitly say so, the authorship of the name — i.e., who first made it available and when — has remained in limbo for decades. Until we took a closer look.

While researching the etymology of the name (more on that below), we also researched its publication history looking for its first available use. Not surprisingly, we found it in the Zoological Record for 1958 (published in 1961),* in which Paracottus (Leocottus) pelagicus is designated as the type. The author of Leocottus, unintentionally, is G. Palmer, British Museum (Natural History), a compiler for the Zoological Record.

As for the etymology of Leocottus, Taliev was equally non-committal. Cottus, of course, is the type genus of the sculpin family Cottidae. But what does “leo” mean? Lion, maybe? But there is nothing lion-like about L. pelagicus as far as we can tell (it doesn’t have mane). Perhaps “Leo” is short for “leios,” meaning smooth. But there is already a sculpin genus Leiocottus Girard 1856 from the Pacific coast of North America, named for its “perfectly smooth” skin. And there is nothing in Taliev’s description of the species and subgenus that stands out as being “smooth.”

Our best guess is that “Leo” refers to Russian ichthyologist Lev (or Leo) Semyonovich Berg (1876-1950). Berg wrote several papers on Lake Baikal sculpins that Taliev cited in his monograph, and described over a dozen sculpin taxa himself. If we are correct, then Leocottus means “Leo’s sculpin.”

* Our thanks to Johannes Müller, who skillfully navigated Covid-19 restrictions at the Naturalis Library (Leiden, Netherlands) to scan the 1958 Zoological Record for us.

8 September

Humble-bragging

Humble-bragging is defined as “the action of making an ostensibly modest or self-deprecating statement with the actual intention of drawing attention to something of which one is proud.”

Recently, we’ve been gratified to see our humble ETYFish Project cited in two peer-reviewed publications. It was especially gratifying to see our first-ever citation in Ichthyology & Herpetology (formerly Copeia), the quarterly publication of the American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists and one of the most respected ichthyological journals in the world.

Yellowtail Damselfish, Microspathodon chrysurus, adult. Courtesy: Wikipedia.

The citation appeared in a major new study, “Systematics of Damselfishes,” by Kevin L. Tang, Melanie L. J. Stiassny, Richard L. Mayden, and Robert DeSalle (Ichthyology & Herpetology 109, No. 1, 2021, 258-318). The authors proposed a number of generic reassignments and other taxonomic changes, all of which have been incorporated into our etymological coverage of the family. The ETYFish Project is cited in the section discussing the genus Microspathodon. The authors write:

This genus is composed of four species from the Atlantic and eastern Pacific, three of which are found in rocky habitats, with the fourth (Microspathodon chrysurus) inhabiting coral reefs. The name likely derives from their distinctive dentition (Jordan and Evermann, 1898: 1565; Scharpf and Lazara, 2020).

While we love being cited alongside David Starr Jordan, Barton Warton Evermann, and their legendary four-volume Fishes of North and Middle America (1896-1900), we wish the authors had included more of our etymological explanation, which involved an extra bit of research —the actual examination of a preserved Microspathodon specimen in Australia. You can read the full story at our 29 August 2018 “Name of the Week.”

The second recent citation calls us out for two oversights. The paper is “Historical review on the type locality of Knodus victoriae (Steindachner 1907) (Teleostei: Characidae) and Loricaria parnahybae Steindachner 1907 (Teleostei: Loricariidae),” by Rayane Gonçalves Aguiar, Erick Cristofore Guimarães, Luis Fernando Carvalho-Costa, and Felipe Polivanov Ottoni (Biota Neotropica 21, No. 4, art. 20211226: 1-4).

Knodus victoriae. From: Eigenmann, C. H. 1918. The American Characidae. Part 2. Memoirs of the Museum of Comparative Zoology v. 43 (pt 2): 103-208, Pls. 3, 8-11, 13, 16-29, 33, 78-80, 93, 101.

Our entries for Knodus victoriae and Loricaria parnahybae stated that the type localities for both species is Victoria, a town near the mouth of the Parnaíba River in Brazil, as reported in Steindachner’s original descriptions. But, as the authors point out, Victoria is actually located in the upper Parnaiba River basin, not in its lower portion (near the mouth). Also, the “Victoria” name is no longer used; it should be called “Alto Parnaíba municipality.” The authors suggest that our use of “Victoria” creates “doubts and confusion that hinder biogeographic and taxonomic studies.”

Even when we’re wrong, it’s nice to be cited. That means others are paying attention to and finding value in our work. The entries have been revised.

Note: Aguiar et al. cite “Scharpf & Kenneth 2021” in their text. The correct citation is “Scharpf & Lazara 2021.” Just sayin’.

1 September

Holotypes “collected” by other animals

Several new fish species have been described from the stomachs of other animals. We don’t have a precise number. Our quick survey revealed at least a dozen species whose names reflect the fact that they were eaten before they were discovered. Here’s a handful of these names. The final two made us laugh.

Haplochromis avium Regan 1929 The name of this cichlid from Africa’s Lake Albert means “of birds.” The specimens Regan examined were all collected from the stomachs of cormorants.

Prognathodes aya. Photo by James Garin. Courtesy: Shorefishes of the Eastern Pacific Online Information System. https://biogeodb.stri.si.edu/caribbean/en/thefishes/species/3847

Prognathodes aya (Jordan 1886) This butterflyfish (Chaetodontidae) occurs in the western Atlantic from North Carolina to the Gulf of Mexico. It was named for the Red Snapper, Lutjanus aya (now known as L. campechanus), from whose stomach the holotype was — and these are Jordan’s words, not ours — “spewed up.”

Leuroglossus callorhini (Lucas 1899) This deep-sea smelt (Bathylagidae) from the Bering Sea is named for the Northern Fur Seal, Callorhinus ursinus, which “extensively” feeds on this species and from whose stomach the type material was collected. “Owing to the tenderness and small size of this fish,” Lucas wrote, “it is so quickly acted on by the gastric juice that nothing but bones remained of the many hundred specimens that were seen and while evidently common, it can be described only from the skeleton.”

Neopagetopsis ionah Nybelin 1947 The biblically inspired name of this crocodile icefish, discovered from the stomach of a whale, is covered in the 29 January 2020 “Name of the Week.”

Hyporthodus exsul (Fowler 1944) The name of this rare grouper from the western coast of Mexico and Central America means “exile.” Why? Because the holotype was exiled to the stomach of a Black Skipjack Tuna, Euthynnus lineatus.

Our runner-up favorite:

Ethadophis merenda Rosenblatt & McCosker 1970 This snake eel (Ophichthidae) from Baja California, Mexico, was taken from the stomach of a White Sea Bass, Cynoscion nobilis. “Merenda” is Latin for “afternoon snack.” Its common name is Snack Eel.

Our favorite:

Paraliparis infeliciter Stein, Chernova & Andriashev 2001 This South Australian snailfish (Liparidae) is known from only one specimen eaten by an Orange Roughy, Hoplostethus atlanticus. Its Latin name means “bad luck.”

Live coloration of Paracanthopoma saci. From: Dagosta, F. C. P. and M. de Pinna. 2021. Two new catfish species of typically Amazonian lineages in the Upper Rio Paraguay (Aspredinidae: Hoplomyzontinae and Trichomycteridae: Vandelliinae), with a biogeographic discussion. Papéis Avulsos de Zoologia (São Paulo) v. 61: e20216147: 1-23.

25 August

Paracanthopoma saci Dagosta & de Pinna 2021

The name of this new species of vandelliine catfish has a clever double meaning.

Paracanthopoma saci is known only from the Rio Taquarizinho, a tributary of the Rio Taquari in Rio Paraguay drainage of Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil. It occurs over fine sand in clear, slightly milky water 30 to 150 cm deep. The elevation of the stream is 363 meters.

The specific epithet saci is an acronym, named for the SACI expedition — South American Characiform Inventory — which collected the first known specimen of this species. But that is only half the name’s meaning. “Saci” also refers to saci-pererê, the name of a supernatural entity in Brazilian folklore personified as a nocturnal, one-legged, hopping, red-capped, pipe-smoking boy who turns into dust devils and is fond of terrorizing or at least annoying people and other animals.

Paracanthopoma saci clearly annoys other animals. It’s a member of the trichomycterid subfamily Vandelliinae, which the authors of the description categorize as the “only exclusively hematophagous gnathostomes besides vampire bats.” In other words, they feed on blood. Vandelliines enter the gill cavity of larger fishes, lacerate a blood vessel, gorge on blood, and leave. Annoying, indeed.

Vandelline catfishes terrorize humans as well. They are reputed to enter the urethra and vaginal canal of human bathers. Most accounts have been discredited as myth or superstition. A modern account reported in a medical journal is disputed. But still, the thought of a vandelline catfish swimming up your privates is enough to make you cringe and think twice about what you do in the water.

Saci-pererê would no doubt approve.

Paraliparis freeborni. From: Stein, D. L. 2012. A review of the snailfishes (Liparidae, Scorpaeniformes) of New Zealand, including descriptions of a new genus and sixteen new species. Zootaxa No. 3588: 1-54.

18 August

Paraliparis freeborni Stein 2012

What do the film Saving Private Ryan and the four-volume book Fishes of New Zealand have in common? They both contain contributions from artist Michelle Freeborn.

Freeborn studied art and design in England. She then went on to work in the British Film Industry for 15 years in special make up, costume and model making. Her credits include “art finish and hair punching” for Steven Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan, and foam and latex fabrication for Lost in Space. (What is hair punching? It’s the application of individual hairs onto prosthetic makeup appliances.)

In 2001, Freeborn moved to New Zealand and learned about a job at Te Papa Tongawera, the Museum of New Zealand, illustrating fishes for an upcoming book. She knew nothing about fishes but that didn’t stop her from applying for the job. She bought a fish at a local market — the Red Gurnard Helicolenus percoides — drew it, and presented it during her interview. Andrew Stewart, the fish collection manager at Te Papa, said: “It was very obvious that she has identified and captured the essence of a difficult species very clearly.” She got the job.Freeborn perfected her technique over the next month. In many cases she was able to go from a blank sheet to a finished drawing in a single day. Stewart said: “With growing confidence Michelle has started to observe characters and morphologies which had escaped even the experts. In some cases we have had to revise our identifications.”

One of Freeborn’s biggest fans is snailfsh (Liparidae) taxonomist David L. Stein. In 2012, he named a snailfish — known only from the holotype, taken on the Chatham Rise off New Zealand at a depth of 1218 m — in her honor. She illustrated 34 species for Stein, for a total of 83 drawings. These included not only fully detailed lateral views, but also drawings of anatomical details and internal structures after dissection.

Stein later wrote: “She is efficient, patient (important when a drawing must be repeatedly revised to get it perfect), precise, and a pleasure to work with. Furthermore, she is a quick study — fish anatomy is an exacting discipline, and requires that the artist understand what is being drawn and its function, so that it can be properly rendered. Once the function of an anatomical feature has been explained to Michelle, she applies that knowledge to future drawings.”

You can sample some of Freeborn’s work, cinematic and ichthyological, at her website. You can watch Freeborn demonstrate her technique here:

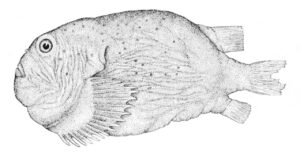

Aptocyclus ventricosus. From: Hart, J. L. 1973. Pacific fishes of Canada. Bulletin of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada Bull. 180: 740 pp.

11 August

The potbellied, urine-squirting lumpfish that’s also a pervert (allegedly)

Poor Aptocyclus ventricosus. First of all, it’s called a lumpfish. The Smooth Lumpfish. Or, even worse, Smooth Lumpsucker. Neither “lump” nor “sucker” conjures images of a sleek, fast-swimming predator that puts up a fight when hooked and tastes great when grilled with chili powder and a wedge of lime. Nor does it sound like a perky, bright-colored denizen of a coral reef. Instead, it’s a globular, scaleless, muddy-gray fish that inhabits the cold, deep waters (up to 1700 m) of the North Pacific.

The “sucker” part of its name refers to its ventral fins, which are joined to form a circular adhesive disc, a fact reflected in its generic epithet: [h]apto, to fasten or bind, and cyclos, circle or ring. The “lump” part alludes to its inclusion in the lumpfish family Cyclopteridae (also named for the adhesive disc-like ventral fins). Many lumpfishes have a first dorsal fin so enveloped by a thick and tubercular skin that it looks like a lump instead of a fin, hence the moniker. The Smooth Lumpsucker has no such lump. Its first dorsal fin is completely embedded in the skin. The second dorsal fin looks pretty much normal.

The specific name “ventricosus” dates to naturalist and explorer Peter Simon Pallas (1741-1811), who described the species in 1769. Pallas, as far as we can tell, had no first-hand knowledge of the fish. Instead, he based his description on an unpublished manuscript written by Georg Wilhelm Steller (1709-1746), a German physician-naturalist who explored the Kamchatka Peninsula and what is now Alaska in 1740 and 1741, during which he discovered lots of animals, including this fish. “Ventricosus” is Latin for potbellied or bulging. Steller described the fish as having two exceedingly large urinary bladders, which, per Pallas, can cause an “unsightly belly size” (translation). When Steller pressed the belly, he said the fish squirted urine.

While skimming through Pallas’ Latin text for the meaning of “ventricosus” we came across a passage that stopped us in our tracks. “What the [expletive]?” we muttered. Surely our poor attempt at translation was deceiving us. We consulted two scholars fluent in Latin, Holger Funk and Ron Fricke, who confirmed what our eyes could scarcely believe. According to Steller, via Pallas:

“There is an absurd accusation among the people of Kamchatka who consider this fish libidinous and lewd because it always has its eyes turned upwards in order to catch a glimpse of the sacellum [little sanctuary] under the skirts of ladies bathing at the beach.”

Lawyers for the Smooth Lumpsucker deny the allegation.

4 August

Hypostomus guajupia Penido, Pessali & Zawadzki 2021

It is one of the largest mining disasters ever. On 25 January 2019, Dam I, a tailings dam at the Córrego do Feijão iron ore mine, near Brumadinho, Minas Gerais, Brazil, collapsed. A tailings dam is an embankment used to store, presumably forever, the highly toxic metal wastes that are generated as iron-ore is extracted from the ground. But the Brumadinho dam’s lifespan fell tragically short of forever. Just after noon, at 12:28 PM, the dam collapsed. An estimated 12 million cubic meters of toxic waste and mud swept through the mine’s offices (including a cafeteria where employees were eating lunch), and through homes, farms, inns, and roads downstream. At 3:50 p.m., the mud reached the Paraopeba River, which supplies water to one third of the Greater Belo Horizonte region.

The collapse killed 270 people, of whom 259 were officially confirmed dead. The bodies of 11 others have not been found. In addition, the collapse caused fish death, habitat loss through siltation, increased turbidity, heavy metal contamination, and temporary oxygen depletion in the Rio Paraopeba.

Hypostomus guajupia is a new species of loricariid catfish that occurs in the Rio Paraopeba, directly within the dam’s path of destruction. The authors named it after Guajupiá, the Tupí-Guaraní name for a mythical place analogous to the Fields of Reeds for the ancient Egyptians, the Elysian Fields for the classical Greeks, and Heaven for Christians, a “place beyond the mountains, where the righteous souls would meet their ancestors and live eternally in health, justice, pleasure and joy,” in tribute to the 270 people who died when the Brumadinho dam collapsed.

The impact of the dam disaster on the population status of Hypostomus guajupia — and for the freshwater biota of the region as a whole — are not yet known.

In September 2019, Brazilian police indicted Vale, the mining company that owns the dam, the testing service TÜV SÜD, and 13 employees of the two companies for producing misleading documents about the safety of the dam. The precise cause of the collapse has not yet been determined, but experts agree that tailings dams are extremely vulnerable to liquefaction when the tailings behind the dam are saturated with water. The liquid mixture erodes the structure of the dam and increases the potential for a rupture.

Brumadinho was not the first tailings dam disaster in Brazil. On November 5 2015, a tailings dam at the Germano iron ore mine near Mariana, also in Minas Gerais, suffered a catastrophic failure. Although fewer people died (19), the environmental devastation from the collapse is the largest ever recorded, with pollutants spreading along 668 km (415 m) of watercourses.

There are over 1700 tailings dams worldwide. Of them, 687 of them are classified as “high risk” if their collapse would cause extreme or catastrophic danger to nearby communities, including mass fatalities.

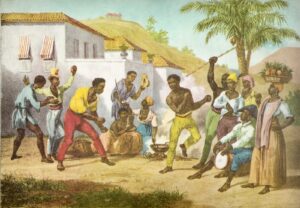

Capoeira or the Dance of War, painting by Johann Moritz Rugendas, ca. 1825.

28 July

The Capoeira Catfishes

The authors of two new species of loricariid catfishes from Brazil must be fans of the Brazilian martial art capoeira. Because they named them after master practitioners — capoeiristas — of the “Dance of War.”

Capoeira has a fascinating history. It was created by Africans and African descendants enslaved by Portuguese colonists in 16th– to 19th-century Brazil. The Portuguese forbade the slaves to practice any kind of fighting that could one day be used against them. They also forbade any displays of traditional African customs. So the slaves created something new, a form of combat disguised as dance. When the Portuguese were present, it seemed the slaves were dancing. When the slaves were alone, the original intentions of capoeira became clear: learn, practice and perfect combat skills that can one day be used against their captors. The word “capoeira” is said to derive from the Tupí words ka’a (forest) and paũ (round), referring to areas of low vegetation in the Brazilian interior where fugitive slaves would hide.

When slavery was declared illegal in Brazil in 1888, many free former slaves were abandoned. There was nowhere to live. Jobs were scarce. They were despised by Brazilian society. Desperate for food and money, many capoeiristas turned to crime, working for criminals and warlords as body guards and assassins. Capoeira was declared illegal. Anyone caught practicing capoeira, even for fun, would be arrested, tortured and often mutilated by the police. By the 1920s, strictures against capoeira began to ease. It was legalized in 1930.

The two new “Capoeira Catfishes” were described by Cláudio Henrique Zawadzki and Iago de Souza Penido in the journal Ichthyological Exploration of Freshwaters (24 June 2021). Both species are currently only known from the main channel of the Rio São Francisco downstream of Paulo Afonso IV dam, at the border of Bahia and Alagoas States, Brazil.

Hypostomus bimbai is named in honor of José Manoel dos Reis Machado (1899-1974), commonly called Mestre Bimba, i.e., a master capoeirista. He created the Regional style of capoeira characterized by more acrobatic moves and more aggressive punches, and was responsible for the legalization of capoeira in 1930.

Hypostomus pastinhai is named in honor of Vicente Joaquim Pereira (1889-1981), aka Mestre Pastinha. He was the “symbolic patron” of the Angola style of capoeirista, which is characterized by being more rhythmic, slow and malicious, with somewhat creeping movements low to the ground.

These are not the first fishes named for a capoeirista. In 2016, Peixoto & Wosiacki described Eigenmannia besouro, a knifefish (Gymnotiformes: Sternopygidae). “Besouro” is Portuguese for beetle, named in honor of Manoel Henrique Pereira (1895-1924), known as Besouro Mangangá (The Mangangá Beetle), a native of the Recôncavo region of Bahia, Brazil (where this knifefish occurs), and a legendary capoeirista.

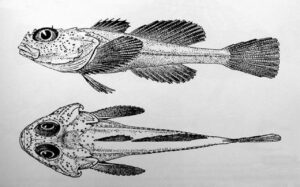

Cottus perplexus. From: Gilbert, C. H. and B. W. Evermann. 1894. A report upon investigations in the Columbia River basin, with descriptions of four new species of fishes. Bulletin of the U. S. Fish Commission v. 14 (art. 16) (for 1894): 169-207, Pls. 16-25.

21 July

Cottus perplexus: a perplexing name

The Reticulate Sculpin Cottus perplexus occurs in freshwater Pacific-slope streams in Washington, Oregon, and northern California, USA. Its name, perplexus, has two definitions: (1) perplexing, confusing, ambiguous, or puzzling, and (2) entangled, interwoven, involved or intricate. Which meaning did the authors, Gilbert & Evermann 1894, have in mind? They did not say.

When considering the meaning of an ambiguous name, we look to see if the same name has been used by other taxonomists, be it for fishes, plants, insects, and so forth. Among fishes, the adjective perplexus has been used three other times. In chronological order they are:

- Eustomias perplexus Gibbs, Clarke & Gomon 1983, a barbled dragonfish from the Western Pacific of China and Papua New Guinea — name means puzzling, referring to its “perplexing combination” of characters seen on two related species, E. longibarba and E. curtatus

- Hyporthodus perplexus (Randall, Hoese & Last 1991), a grouper from Cape Moreton, Queensland, Australia — name means puzzling, referring to its “many peculiarities” (per Randall et al. 1993): known from only a single specimen and “surprising” that more have not been found; lack of additional specimens; and “puzzling” absence of any highly diagnostic characters, apart from its unusually low (13) number of soft dorsal-fin rays

- Scopelogadus perplexus Kotlyar 2021, a bigscale (Melamphaidae) from equatorial and tropical waters of the Pacific — name means confusing or ambiguous, referring to how it had been misidentified as two other species of the genus, S. mizolepis and S. bispinosus

Note that in all three examples, the perplexus adjective refers to some sort of taxonomic confusion about the fish. But the authors of Cottus perplexus did not indicate any such uncertainty or ambiguity in their description. Their account clearly differentiates this sculpin from its closest congener, C. punctulatus. Gilbert & Evermann even say its “body is deeper and more compressed than in any other species known to us …”. From a taxonomic standpoint, there’s nothing perplexing about it.

Which brings us to the second meaning of perplexus — entangled, involved, intricate, etc. Might this adjective refer to the fish’s color pattern? Here’s how the authors described it:

Color in alcohol, back and sides with vermiculations of light and dark, the back with 5 or 6 ill-defined black crossbars, which usually reach the lateral line; the usual black bar at base of caudal, emarginate posteriorly; below the lateral line a number of small, quadrate, dark blotches, arranged in two irregular series; lower parts unmarked except with fine dark punctulations; dorsal, pectoral, and caudal fins crossbarred with dark; anal and ventrals with numerous small dark specks.

Whether this describes an “intricate” or “complex” color pattern — a highly subjective assessment — is impossible to say. The illustration the authors provided (shown here) does not show an intricately patterned fish in our opinion.

Ichthyologist Peter B. Moyle was perplexed by the name. In his excellent book Inland Fishes of California (2nd ed., 2002), his attempt to explain the name clumsily covers both explanations: “Perplexus translates as perplexing,” he wrote, “reflecting the difficulty in defining the species, although Gilbert and Evermann may have had the reticulated appearance in mind when assigning the name.”

Another perplexity: We don’t know who coined the common name Reticulated Sculpin for this species, but it does not seem reticulated (arranged or marked like a net or network) to us. The authors described vermiculations (marked with sinuous or wavy lines), not reticulations.

And yet another perplexity: The junior author of the name, Barton Warren Evermann, was also the junior author of the four-volume Fishes of North and Middle America. In volume two (1898), he and senior author David Starr Jordan explained that perplexus means “perplexed.” Not perplexing. Perplexed. Note the difference. “Perplexing” connotes that there is something about the sculpin that is confusing to those who study it. “Perplexed,” however, suggests that it is the sculpin itself that is confused or troubled by deep uncertainty. We pondered this for a bit but dismissed it as silly.

All we can say with any confidence is that the name perplexus describes itself. And those who attempt to explain it.

Pylodictis olivaris. Photo by Eric Engbretson, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

14 July

Pylodictis — real and imagined

Pylodictis — with one species, the very real Flathead Catfish of North America — may be the only valid genus named after an imaginary fish.

Constantine Rafinesque (1783-1840) described the Flathead Catfish as Silurus olivaris, from the Ohio River, in 1818. Silurus was a catch-all genus for freshwater catfishes, and olivaris means olive-colored, referring to its body color, which Rafinesque described as “olivaceous, shaded with brown.” The next year Rafinesque described another catfish from the Ohio River, which he named Pylodictis limosus.* The meaning of the generic name requires a little guesswork, especially since Rafinesque took a careless (or creative, depending on your point of view) approach to the spelling of Greek and Latin words. Pylodictis is probably a combination of pelos (Greek for mud) and ictis, a variant spelling of ichthys (Greek for fish), with the “d” likely inserted for euphony. The specific epithet, limosus, is Latin for muddy. Both parts of the name reflect two of the common names Rafinesque reported for the fish — Mudcat and Mudsucher (Mudsucker) — and the fact that it “lives in the mire” (“vit dans la fange”).

For reasons unexplained, Silurus olivaris does not appear in Rafinesque’s Ichthyologia Ohiensis (1820), whereas Pylodictis (now spelled Pilodictis) limosus — called the “Toad Mudcat” — gets a more detailed account, this time in English. “I have not seen this fish,” Rafinesque wrote, “but describe it from a drawing of Mr. Audubon. It is found in the lower parts of the Ohio and in the Mississippi, where it lives on muddy bottoms, and buries itself in the mud in the winter. It reaches sometimes the weight of 20 pounds. It bears the name of Mudcat, Mudfish, Mudsucker, and Toadfish. It is good to eat and bites at the hook.”

Mr. Audubon is John James Audubon (1785-1851), the famous American ornithologist, painter, and namesake of the National Audubon Society. In 1818, Rafinesque was a guest at Audubon’s Kentucky home. In the middle of the night, Rafinesque noticed a bat in his room that he thought was a new species. He grabbed Audubon’s favorite violin in an effort to knock the bat down. We do not know the fate of the bat. The violin, however, was destroyed.

In 1877, David Starr Jordan reviewed Rafinesque’s contributions to American ichthyology. He determined that Silurus olivaris was the senior synonym of Pylodictis limosus. Since the catfish was distinct enough to warrant its own genus, Jordan settled on Rafinesque’s Pylodictis, the oldest available name. Silurus olivaris thus became Pylodictis olivaris (although Jordan attempted to correct Rafinesque’s spelling, unnecessarily changing “Pylodictis” to “Pelodichthys.”)

At around this time, American naturalists were beginning to realize that Audubon had pranked Rafinesque, presumably in retaliation for the broken violin. Audubon described and/or sketched a number of fictitious, even fantastical, fishes, which the gullible Rafinesque described as real. These included a sunfish with a dorsal fin resembling that of the dolphinfish or mahi-mahi (Coryphaena), with a single long, spiny ray beginning behind the head and ending near the tail, and a 10-foot long “devil jack diamond-fish,” an alligator gar with bullet-proof scales. Jordan knew of these fabrications, but apparently not all of them.

Jordan retained the name Pylodictis, presumably unaware that the type species, Pylodictis limosus, lived only “in the mire” of Audubon’s vengeful imagination.

* Perhaps as evidence of Rafinesque’s eccentricity — or sloppiness as a taxonomist — he proposed several other names for the Flathead Catfish: Ilictis limosus, Leptops viscosus and Opladelus nebulosus.

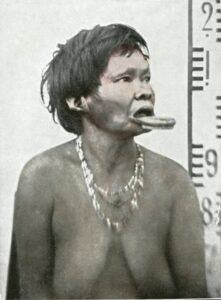

Botocudo woman (circa 1900) with the botoque in the lower lip (source: Wikipedia).

7 July

Austrolebias botocudo and Austrolebias nubium