NAMES OF THE WEEK from: 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2023 2024 2025

28 December

Obscenity in disguise: the Uranoscopus or Stargazer

Ed. note: While re-researching the generic name Callionymus Linnaeus 1758, I found a reference that said the name “refers euphemistically to a sex-related name of the same organism” without any additional explanation. Intrigued, and suspecting that the etymology of Callionymus traces back to the ancients, I contacted our resident expert on ancient names, Dr. Holger Funk, who filed the following report. Warning: his findings are for mature audiences only!

Ancient writers were not particularly prudish. Poets filled their comedies and satires with ribald scenes and expletives. Ancient scholars, however — philosophers, historians, lexicographers and naturalists — writing for a more educated audience, shied away from calling things by their everyday names, preferring to paraphrase them, often using rhetorical devices such as euphemisms (mild or indirect substitutions for unpleasant or embarrassing words) or antiphrasis (the use of words in senses opposite to their generally accepted meanings). An example in this respect is the fish the ancient Greeks called Uranoscopus.

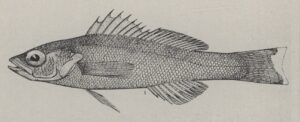

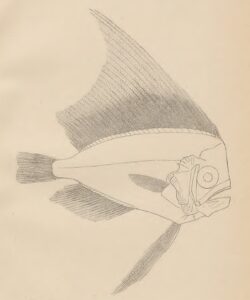

“Uranoscopus” is a Latinization of οὐρανός (ouranós), heaven or sky, and σκοπός (skopós), looker, contemplator or viewer. Taxonomists have called this fish Uranoscopus scaber since Linnaeus. Its common name in English is Stargazer.

Head of a Stargazer buried in sand or gravel with reddish “fishing line” (center) to attract prey. © Giuseppe Piccioli.

Uranoscopus scaber is widespread in the eastern Atlantic, from the British Isles across North Africa to Mauritania, and in the Mediterranean and Black Seas. The average length is 22 cm, the maximum length is 40 cm. It is a bottom fish, active only at night, at depths of 15 to 400 m, where it spends most of its time buried in sand or gravel, out of sight of predators and prey. Buried in, only the eyes look out upwards, hence the name Stargazer. It has a mobile, membranous appendage on its mouth that is used to attract prey (pretending to be a kind of tubeworm ). In the Byzantine encyclopedia Suidas the Uranoscopus was also called κλέπτης (kléptēs), nocturnal trickster, because of its sneaky trapping technique. Apart from that, it was considered a common food fish in ancient times, even if its culinary quality was disputed.

The Uranoscopus had a second popular name, and here is where things get risqué. This name was “Callionymous,” a Latinization of Καλλιώνυμος (kalliṓnymos), which in turn is composed of two terms: κάλλεος (kálleos), genitive of κάλλος (kállos), beauty, and -ώνυμος (-ṓnymos), named, derived from ὄνομα (ónoma), name. Together: “having a name of beauty” or simply “having a beautiful name.”

“Callionymous” alluded to Uranoscopus (“stargazer”), a pretty name for a fish that itself isn’t particularly pretty. (It is no coincidence that Linnaeus gave it the epithet scaber, rough or scurfy.) Christians in the Middle Ages viewed the fish favorably, since anyone who gazes upward, towards Christ or God, is therefore safe from temptation. Appropriately, one of its various Greek names was also ἁγνός (agnós), the chaste one.

Neither Uranoscopus nor Callionymous suggests anything ugly, ambiguous or reprehensible. But the supposedly chaste fish led a double life, so to speak. The Greek grammarian and lexicographer Hesychius of Alexandria (5th or 6th century AD) was the first to bashfully point out this in his dictionary of unusual and obscure ancient Greek words:

“Kallionymos – a kind of fish. In a figurative sense, some have also used the expression for male and female pudenda.”

Salviani’s copper engraving of the Stargazer (1558: 196v).

Male and female pudenda? Hesychius suggests something lewd or bawdy but exercises polite restraint. Fortunately, for us, the first Renaissance ichthyologists — namely Belon (1553: 217), Rondelet (1554: 306) and Salviani (1558: 197v) — did not hold back. They listened to the colloquial language of their humble, illiterate countrymen, who talked unaffectedly. To quote Rondelet, who provided the most concise (i.e., explicit) account:

“But just as the Uranoscopus had been given a beautiful and honorable name by the ancients, so it was given an ugly and indecent name by the people of Marseilles, which an honorable woman, out of shame, scarcely dared to utter. The fish was called tapecon by these people because it seemed to resemble a pessary in shape, and raspecon because the rough head could be used to incite the female pudendum.”

In order to fully appreciate Rondelet’s explanation, one needs to know that pessaries were used as a gynecological aid in ancient times, just as they are used nowadays. The term pessary comes from the Greek πεσσός (pessós) and Latin pessum or pessus, a plug of wool or lint. Apparently, such pessaries could also be used as sex toys. And if common means of joy were not at hand, they would be replaced with substitutes, even, we are told, with a rough-headed fish like the Uranoscopus. In view of the testimonies of different provenance, it would be too easy to dismiss this as just male fantasy.

The colloquial terms Tapecon and Raspecon likewise need explanation. According to linguists Behrens & Haust (Wortgeschichtliches, 1909: 151–152), the two terms originated through a a transformation and interchange of letters and syllables, a so-called “reciprocal metathesis,” typical for Romance languages. In the present case it took place in two steps: the Latin name uranoscopus first became the Frenchized uranoscopon, then later was mangled once more to raspecon, tapecon and other similar expressions, with the ichthyological origin of the words now lost and unrecognizable.

Callionymous, by virtue of its being a synonym for Uranoscopus, also became a term with a sexual connotation. Indeed, “having a beautiful name” is a lovely euphemism for body parts that should not, in polite company, be named.

Ed. note: Today, Uranoscopus Linnaeus 1758 refers to stargazers (Uranoscopidae) and Callionymus Linnaeus 1758 refers to an unrelated genus, dragonets (Callionymidae). Linnaeus, believing that stargazers and dragonets were closely related, followed his colleague Peter Artedi in adopting both ancient names, selecting Uranoscopus for the fishes with the upturned eyes and Callionymus for the dragonets. Whether Linnaeus was aware of the hidden meanings behind the names is unknown.

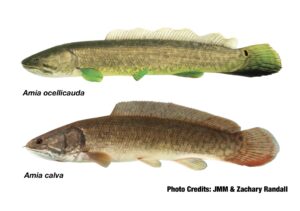

Richardson’s selection of the name Amia ocellicauda was percipient since this bowfin’s caudal ocellus (eyespot) is more pronounced in males than that of the nominate species, Amia calva.

21 December

Amia ocellicauda Richardson (not Todd) 1836

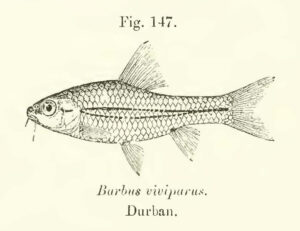

Ichthyologists have long suspected that the Bowfin Amia calva — the sole surviving member of a family of fishes (Amiidae) that populated fresh and marine waters 135-195 million years ago — represents two or more extant species. Now researchers have confirmed this suspicion. Using genomic data in conjunction with several different phylogenetic and population genetic analyses, they demonstrated that individuals from the Great Lakes to the Mississippi River basin, west of the Appalachian Mountains, represent Amia ocellicauda (first described in 1836) rather than the widely recognized A. calva, now restricted to the Pearl River in Louisiana and Mississippi to the Florida Peninsula, and rivers draining to the Atlantic Ocean in Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina and Virginia.

You can read their paper here.

Unfortunately, the authors perpetuated a mistake in the authorship of the name. They date Amia ocellicauda to “Todd in Richardson 1836,” meaning that Todd named the bowfin within a publication written or edited by Richardson published in 1836. Actually, while Todd provided a descriptive account, the name was proposed and made available by Richardson. Hence, authorship of Amia ocellicauda should be “Richardson 1836” or “Richardson (ex Todd) 1836.”

The authors of the paper did not originate this mistake. It had become entrenched in the literature and was given incorrectly in Eschmeyer’s Catalog of Fishes. As I was adding Amia ocellicauda to ETYFish I noticed the error and contacted Ron Fricke, one of ECoF’s editors. The authorship of the name has been corrected in their database.

Richardson was Scottish surgeon-naturalist John Richardson (1787‒1865), the author of the fish section of “Fauna Boreali-Americana,” an important early work on the fishes of Canada, western North America and the Arctic circle. He collected many of the fishes he described himself. But he also relied on the “exertions of others” (to use his words). The “Todd” in the case of A. ocellicauda was “Mr. Todd, surgeon of the Naval depôt,” a Royal Navy depot at Lake Huron, the type locality. Richardson did not supply Todd’s first name but I have found several records indicating that a “C. C. Todd,” a medical officer with an interest in natural history, lived or was stationed at Penetanguishene, Ontario, on the shores of Lake Huron.

Richardson wrote: “Mr. Todd sent me a notice of a Lake Huron fish, named locally Poisson de Marais [Marsh-fish]. It is speared by the Indians in the rushy shallows which it frequents, but is seldom eaten by the settlers. A specimen which Mr. Todd prepared, being unfortunately destroyed by vermin, never reached me, but his short description corresponds with the characters of the genus Amia, though the gill-rays are fewer than in the Carolina species.”

Richardson quoted Mr. Todd’s “in lit.” description of the bowfin and gave him credit for it. But Mr. Todd did not supply a Latin or scientific name. Since it was Richardson who coined “ocellicauda” — referring to the bowfin’s prominent ocellus or eyespot on the upper caudal-fin base of males — and affixed it to Mr. Todd’s description, that makes him, not Todd, the author of the name.

Richardson followed this format several times in the same publication in which Amia ocellicauda was proposed. For example, the following fishes were all named by Richardson but based, in part, on unpublished descriptions written by surgeon-naturalist Meredith Gairdner (1809-1837) of the Hudson’s Bay Company (a fur trading company):

White Sturgeon, Acipenser transmontanus

Northern Pikeminnow, Ptychocheilus oregonensis

Redside Shiner, Richardsonius balteatus

Eulachon, Thaleichthys pacificus

Cutthroat Trout, Oncorhynchus clarkii

Prickly Sculpin, Cottus asper

Richardson returned the favor by naming the Columbia River Redband Trout (now Oncorhynchus mykiss gairdneri) after Gairdner. Too bad he didn’t do the same for Mr. Todd.

14 December

Unavailable names (at least for now)

In order for a zoological name to be considered “available” — that is, permanently affixed to a taxon and available for use by other zoologists — it must be proposed in certain ways as required by the International Commission of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN). These rules are explained in my essay, “Fish-centric Guide to Zoological Nomenclature.”

One of the more recent rules was established to deal with the rapid proliferation of electronic publications. Such publications are now regulated by amendments of ICZN Articles 8, 9, 10, 21 and 78. If published electronically (after 2011 only), either for free or behind a paywall, a new-taxon description must be presented in a fixed graphical format (i.e., non-HTML, usually a PDF), with the date of publication stated in the work and the work itself registered in the Official Register of Zoological Nomenclature (ZooBank) with evidence of such registration (a Life Science Identifier, or LSID number) appearing in the text. Descriptions that are printed on paper and distributed or made available for purchase do not require ZooBank registration (but is strongly encouraged nevertheless).

With printing and mailing costs on the rise, concerns over deforestation and the unnecessary use of paper, and the near universal acceptance of PDFs as a convenient scholarly format, many printed journals are suspending hard-copy publication and going all-digital. One such publication is aqua, International Journal of Ichthyology, published by explorer and ornamental-fish wholesaler and supplier Heiko Bleher. In 2021, aqua (not a typo, the journal’s name is all lower-case) quietly announced it was suspending the printed version:

“New Subscription Notice starting with volume 28: Do [sic] to pandemic times we had severe problems worldwide and printing cost went up sky-high, therefore we were forst [sic] to publish only on-line since 2021 but everything else remains same …”

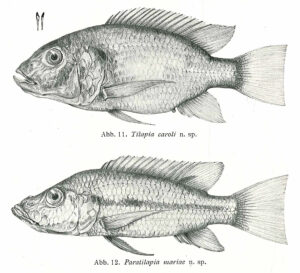

Unfortunately, none of the new-taxon descriptions in all aqua issues after v. 27 (no. 1) (April 2021) have ZooBank registrations. Without ZooBank registration, new taxa published in electronic-only papers are considered “non-existent.” This rule affects 15 new species and one new subgenus recently proposed in aqua. Most of these I’ve already entered into the ETYFish Project not realizing that the journal had ceased hard-copy publication. They are:

A flying barb (Danionidae) from India: Esomus nimasowi Abujam, Gogoi, Das, Das & Biswas 2021, in honor of Gibji Nimasow, Rajiv Gandhi University (Arunachal Pradesh, India), for his “constant encouragement and interest in fishery related works”

A headstander (Anostomidae) from Bolivia: Megaleporinus prochiloides Roberts 2021, –oides, having the form of: referring to its greatly enlarged mouth and lips, strongly resembling those of Prochilodus (Prochilodontidae)

A torrent catfish (Amblycipitidae): Amblyceps motumensis Abujam, Tamang, Nimasow & Das 2022, –ensis, Latin suffix denoting place: Motum River, Siang River drainage, Arunachal Pradesh, India, type locality

Two sand-dwelling gobies (Gobiidae) from the tropical western Pacific: Hazeus ammophilus Allen & Erdmann 2021, ammos, sand; philo, to love, referring to its predilection for sand-bottom habitats; and Hazeus profusus Allen & Erdmann 2021, abundant or profuse, referring to its abundance on sand-bottom habitats [these names made available in November 2023]

Three damselfishes (Pomacentridae): Pomacentrus novaeguineae Allen, Erdmann & Pertiwi 2022, of New Guinea, its main area of occurrence, especially from its northern side and western extremity, where coral reefs are well developed; Pomacentrus umbratilus Allen, Erdmann & Pertiwi 2022, Latin for “of the shade,” referring to its habit of sheltering in the shady recesses of the reef, especially under ledges; and Pomacentrus xanthocercus Allen, Erdmann & Pertiwi 2022, xanthus, yellow; cercus, tail, referring to bright-yellow caudal fin with yellow hue extending forward onto caudal peduncle [these names made available in October 2023]

Three rivuline killifishes (Rivulidae) from Brazil: Anablepsoides falconi Nielsen, Hoetmer & Vandenkerkhove 2022, in honor of Francisco Falcon, musician, photographer and environmentalist; he is also a “great friend” and “excellent” killifish breeder who has developed new breeding techniques and has helped many Brazilians enter the killifish hobby (D. Nielsen, pers. comm.); Anablepsoides katukina Nielsen, Hoetmer & Vandenkerkhove 2022, named for the Katukina, an indigenous group inhabiting the Rio Juruá drainage, Amazon basin, Acre State, Brazil, where this killifish occurs; and Laimosemion anitae Nielsen, Hoetmer & Vandenkerkhove 2022, in honor of Anita Hoetmer, wife of the second author (who is also its discoverer) [these names made available in August 2023]

Four new fish taxa are described in this recent issue of aqua, but the names are not yet available.

The latest issue of aqua (cover shown here) includes the descriptions of four additional new taxa (three species, one subgenus), all missing ZooBank registration. All of these descriptions are important contributions to the scientific record, written by serious, competent ichthyologists. So it’s unfair that their efforts now languish in the nomenclatural limbo of “unavailable” names.

In addition to these aqua papers, I have three more from three other online-only journals in my “No ZooBank/Unavailable” folder, with the descriptions of six putative new species.

Missing ZooBank registration numbers is not unique to fishes. It’s a problem affecting the descriptions of other taxonomic groups as well, involving both well-established journals, serious “open access” journals, self-published journals, and a growing number of predatory journals in which the authors pay to have their papers published with little or no peer review. It seems that many editors and publishers of electronic-only publications are not aware of — or simply do not care about — the ZooBank requirement.

The editors of Eschmeyer’s Catalog of Fishes have alerted the editor of aqua, Paolo Parenti, about the problem. They recommended that the journal publish a follow-up paper that includes ZooBank registrations (which would change the availability dates for the above-mentioned taxa from 2021 and 2022 to at least 2023). Until such time, these names remain “non-existent” for nomenclatural purposes.

Technically, I should delete these taxa from ETYFish. But that’s extra work, not to mention the extra work of reinstating them if and when the ZooBank requirement is fulfilled. Chances are the names of these taxa will, despite their unavailability, make their way into the ichthyological literature, bibliographic indices and various websites anyway. I will add asterisks to their ETYFish entries, but it is not a priority. There are plenty of validly published new fish taxa that deserve my attention first.

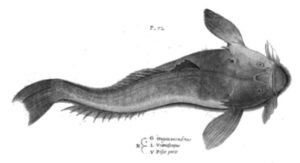

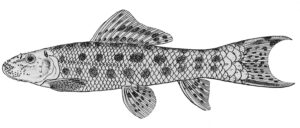

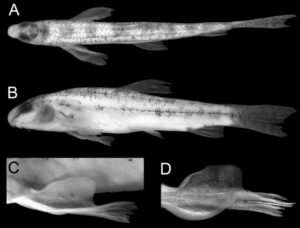

Barbucca diabolica, holotype, gravid female, 23.2 mm SL. Photo by Tyson R. Roberts. From: Roberts, T. R. 1989. The freshwater fishes of western Borneo (Kalimantan Barat, Indonesia). Memoirs of the California Academy of Sciences No. 14: i–xii + 1–210.

7 December

Barbucca diabolica Roberts 1989

It’s always nice to tie up a loose end in the explanation of a name.

With just two species, the family Barbuccidae is the smallest loach family (actually, tied with Ellopostomatidae, also with two species). The type species, Barbucca diabolica, representing both a new genus and species, was described by Tyson R. Roberts in 1989. (In 2012, Maurice Kottelat determined that, due to its distinctive morphology and position outside any other loach sublineage, Barbucca warranted its own family.)

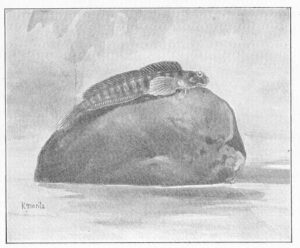

Barbucca diabolica is a small loach, reaching just 2.3 cm. It’s found in small forest streams and backwaters of indonesia. Some references call it a “Scooter Loach” for how its “scoots” instead of swims, with its belly almost always in contact with an object (e.g., rock, tree branch) or substrate as it wriggles and climbs (sometimes upside down). Other references call it the “Fire-eyed Loach” because of its blood-red eyes.

Roberts named the genus Barbucca — barba, Latin for beard or barbel, and bucca, Latin for cheek — referring to a patch of tubercles found on the cheeks of males. The specific epithet is Latin for devilish, from the Greek diabolikós (διαβολικός), referring, per Roberts, to the “glowing red eyes and spiked tail characteristic of the species.”

The “glowing red eyes” reference is obvious. The “spiked tail” reference is not. As you can see from the photo that accompanied the original description (shown here), there is nothing “spiked” about the tail. Nor is the tail mentioned in Roberts’ description. One aquarium website says the name is inspired in part by the loach’s “forked tail,” but the tail is not noticeably forked. It appears truncated or emarginate to me.

I asked Tyson Roberts via email what he deemed “spiked” about the tail. He is retired now, living in Bangkok, and said he didn’t have access to the description. “But supposedly you have access to it,” he wrote, “and the answer to your question should be obvious from reading it.”

I sent Dr. Roberts a PDF of his description and kindly pointed out that the answer to my question was not at all obvious. Receiving the PDF apparently jogged his memory because he quickly replied:

“Yes, the name diabolica refers to the red eyes and the tubercles on the caudal peduncle, present in males and females, that are large are sharp-pointed (although sharp pointed or spike-like is not mentioned in the text).”

Knowing precisely what the fish’s name means is not all that important in the scheme of things. But I enjoy chasing down such arcana. In this case, my curiosity about the fish’s name brought to light a heretofore unnoticed detail about its distinctive morphology.

30 November

Why are some sharks named after dogs and others after cats?

EDITOR’S NOTE: This week’s entry is written by Holger Funk, a Greek and Latin scholar interested in ichthyological writings dating from ancient times to the Renaissance. He has been helping The ETYFish Project improve its coverage of Latin and Greek (especially Greek!) names and etymologies. Along the way, he has made some fascinating and useful discoveries. This “Name of the Week” is one of them. Dr. Funk has declined any formal credit, so let me take this opportunity to acknowledge and thank him for his valuable “behind-the-scenes” contributions to The ETYFish Project.

Some sharks are called “dogfishes.” Others are called “catsharks.” Allusions to both cats and dogs appear in a handful of scientific names. The deepwater catshark (Pentanchidae) genera Bythaelurus, Cephalurus and Halaelurus are based on the Greek noun aílouros (αἴλουρος), meaning cat. Despite its common name, the specific epithet of the Small-spotted Catshark Scyliorhinus canicula is derived from the Latin word for dog (canis). How is it that sharks have been named for both cats and dogs? The “dog” designation dates to the ancient Greeks. The “cat” designation began in the Renaissance. And despite what the venerable Oxford English Dictionary and otherwise dependable ichthyological references (e.g., earlier versions of The ETYFish Project) tell you, catsharks are not named for their cat-like eyes.

The ancient Greeks subsumed sharks under the collective term “dog” (κύων, kýōn) or “sea-dog” (κύων ἡ θαλαττία, kýōn hē thalattía). Like the Greeks, the Romans used the term canis marinus, “sea-dog.” Unlike the comparable English vernacular “dogfish,” which usually applies to smaller sharks, the Greek and Latin terms encompassed larger sharks as well. What’s important to note here is that from ancient times (Homer) to the late Byzantine (ca. 1400), sharks were only associated with dogs, never with cats.

Ancient sea-dogs did not comprise a clearly defined group, yet we know from the works of two Greeks —Aristotle and Oppian (Halieutica, “On Fishing”) — the names of nine species that we can identify more or less well with today’s genera and species. Of particular interest is a species Aristotle calls σκύλιον (skýlion) and Oppian synonymously calls σκύμνος (skýmnos). Both names denote a young animal of different quadrupeds, especially a young dog or whelp. By assigning this name to small sharks, the ancients were saying that small sharks were, in a metaphorical sense, small dogs or whelps compared with larger sharks. Interestingly, both skýlion and skýmnos applied to a young cat or kitten as well, providing an etymological foundation for the curious fact that sharks have been, and still are, referred to as both dogs and cats.

The Romans (mainly Pliny and Ovid), unlike the Greeks, were not very creative when it came to naming fishes. Mostly they adopted Greek names either by transliterating them letter by letter according to the Latin alphabet, but sometime they translated the Greek name into Latin. This happened with the Small-spotted Catshark. Here they translated the aforementioned Aristotelian name σκύλιον as canicula, young dog or puppy (diminutive of canis, dog). However, they were a little creative at least once, using the term catulus alongside canicula, which has nothing to do with cats despite how it sounds (Latin for cat is feles). In fact, catulus is another diminutive for a young animal, particularly a young dog (per Walde & Hofmann, Lateinisches etymologisches Wörterbuch, vol. I, 1938, p. 183).

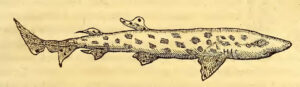

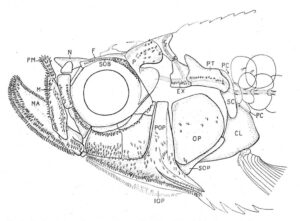

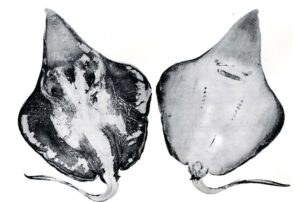

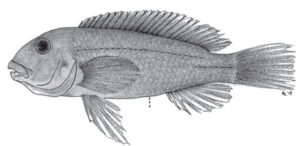

Fig. 1. Rondelet, Libri de piscibus marinis (1554: 383), French version L’histoire entiere des poissons (1558: 300): Latin Canicula saxatilis, called Chat rochier or Catto rochiero (‘Rock cat’) in southern France (= Scyliorhinus stellaris, Nursehound).

These two designations, canicula and catulus, entered scholarly discourse in the 16th century when two pioneers of the burgeoning discipline of ichthyology, the Frenchman Guillaume Rondelet and the Italian Hippolito Salviani, cited the classical Greek and Latin names in their accounts. They also cited the vernacular names of their respective home countries. This is when “cat” first enters the shark lexicon. In France, according to Rondelet (1554), the scyliorhinid “Canicula saxatilis” (=Scyliorhinus stellaris, Nursehound) is known by the local name Chat rochier (“Rock cat”) (Fig. 1). In Rome, according Salviani (1558), “Catulus” (=Scyliorhinus canicula, Small-spotted Catshark), goes by the popular name Pescie Gatto (“Cat fish”) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Salviani, Aquatilium animalium historiae (1558: 137v): Greek Σκύλιον. Latin Catulus, called Pescie Gatto (“Cat fish”) in Rome (= Scyliorhinus canicula, Small-spotted Catshark).

Based on the accounts of Rondelet and Salviani, both the Latin designations and the local vernaculars became firmly established in the ichthyological literature over time. The breakthrough came exactly 200 years later with the 10th edition of Linnaeus’ Systema naturae of 1758, the official starting point of modern zoological nomenclature. Linnaeus knew about Rondelet’s and Salviani’s accounts thanks to the large inventory of ancient fish names compiled by his Swedish compatriot and friend Peter Artedi. Consequently, Linnaeus formally proposed the names Squalus (now Scyliorhinus) canicula and Squalus catulus (the latter now a junior synonym of the former).

The French and Italian “cat” vernaculars eventually made their way into English. In 1812, Thomas Pennant was one of the first to render σκύλιον, canicula and catulus as “Cat fish” in his British Zoology: IV. Fishes (p. 148).

If one surveys the ancient Greek and Latin names, it becomes clear that canine semantics dominated at all times. But why dogs? Were the ancients comparing the light grayish coloring of some sharks to that of dogs? Or was “dog” a derogatory term since the ancients considered sharks inferior in every respect (harmful to humans and unpalatable except as food for the poor)? Could dog be a reference to the voracious, pack-like feeding behavior of sharks in a feeding frenzy? Whatever the explanation, an association with cats is not documented in neither Greek nor Latin. The alleged “cat-like” eyes of certain sharks that have been brought into play can also be ruled out. Palombi & Santarelli (Gli animali commestibili dei mari d’Italia, Milan 2001: 220–222), for example, have noted that in Italian both Scyliorhinus canicula with its relatively large eyes and Scyliorhinus stellaris with relatively small eyes equally are named gatto (kitten). It is more likely that in the national languages that developed from Latin, such as Italian and French, a vulgarization of catulus took place, with the original meaning of “dog” fading more and more until being replaced by the meaning “cat.” All this happened quite unconsciously and without any objective reasons.

The “cat” name for certain sharks is therefore to be regarded as a misunderstanding and misapplication. “Catulus” has nothing to do with cats, and likewise sharks have next to naught in common with cats.

Nannostomus marilynae. Photo by Clinton & Charles Roberston. Courtesy: Wikipedia.

23 November

Marilyn Weitzman (1926-2022)

Earlier this month I learned that Marilyn Weitzman passed away during the summer at the age of 96. News of her death has been hard to come by. No online obituary. Nothing on Facebook. No retrospectives or appreciations. At least none that I could find.

Marilyn Weitzman was the wife of legendary Smithsonian ichthyologist Stanley H. Weitzman (1927-2017; see NOTW, 22 Feb. 2017). Trained in landscape architecture, she became an accomplished ichthyologist herself, specializing in the pencilfishes of the characiform family Lebiasinidae. I once visited the Weitzman lab and it was filled with small aquaria where she bred and raised these small but elegant fishes. Both Weitzmans were equally at home hanging out with members of their local aquarium club (the Potomac Valley Aquarium Society) as they were with fellow ichthyologists. In 2002, I had the pleasure of co-judging the PVAS fish show with them. They were kind and gracious to a fault.

Marilyn learned ichthyology by typing her husband’s papers. While working on a revision of the pencilfishes, Stan asked Marilyn to help. He had done one genus, Nannostomus, but Marilyn could do the rest. It was a small group and would be fairly easy, Stan assured her. “Famous last words,” Marilyn laughed.

Despite her interest in pencilfishes, the two species that Marilyn described or co-described were from other characiform families. In 1985, she described the Veilfin Tetra Hyphessobrycon elachys from eastern Paraguay. Its name, Greek for small, refers to its small adult size, less than 16.6 mm SL, making it one of the smallest known tetras. A year later she collaborated with Smithsonian colleague Richard P. Vari to describe another characid, Astyanax (now Jupiaba) scologaster, from the Río Negro of Venezuela. The name is a combination of skolos, a thorn or pointed object, and gaster, belly, referring to the “exserted spinous pelvic bones” on its ventral surface.

Three of Marilyn’s beloved pencilfishes have been named in her honor:

Nannostomus marilynae Weitzman & Cobb 1975 – This pencilfish (shown here) from the Rio Negro of Brazil and Colombia was named by Stanley Weitzman and J. Stanley Cobb (later a renowned lobster biologist). Stanley honored his wife, stating how Marilyn “has long shared his appreciation for the delicate beauty of members of the genus Nannostomus.”

Lebiasina marilynae Netto-Ferreira 2012 – Brazilian ichthyologist André L. Netto-Ferreira named this pencilfish, described from the headwaters of the rio Curuá in Serra do Cachimbo, Pará, Brazil. Marilyn was honored for devoting her career to the study of fishes of the families Lebiasinidae and Characidae

Pyrrhulina marilynae Netto-Ferreira & Marinho 2013 – Marilyn was honored for her assistance to both authors in their studies of the family Lebiasinidae. This pencilfish occurs in the Rio Tapajós and Rio Xingu of Mato Grosso, Brazil.

Stanley and Marilyn Weitzman had known each other since third grade. They married in 1948 and remained partners in love, family and fishes until his passing in 2017.

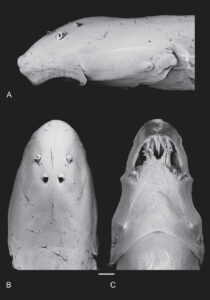

Paracanthopoma truculenta, paratype, SEM images of head. (A) Lateral; (B) Dorsal; (C) Ventral. Scale bar = 500 μm. From: de Pinna, M. C. C., & Dagosta, F. C. P. (2022). A taxonomic review of the vampire catfish genus Paracanthopoma Giltay, 1935 (Siluriformes, Trichomycteridae), with descriptions of nine new species and a revised diagnosis of the genus. Papéis Avulsos De Zoologia, 62, e202262072.

16 November

Bloodsucking demons: 9 new species of “candiru”

Along with vampire bats, hematophagous catfishes of the trichomycterid subfamily Vandelliinae are the only jawed vertebrates that feed exclusively on blood as adults. These South American fishes — popularly known as “candirus” — are infamous for their occasional penetration of human urethras, a fact that has generated a veritable cottage industry of books, articles and TV documentaries, some serious, many sensationalistic. Last week, Brazilian ichthyologists Mário de Pinna and Fernando Cesar Paiva Dagosta published a taxonomic revision of the vandelliine genus Paracanthopoma, in which they described nine new species. The names of all nine species evoke, in one way or another, the feelings of fear, dread and discomfort these “demonic” catfishes elicit in humans.

Paracanthopoma ahriman — named for Ahriman, Persian name of Angra Mainyu, the maker of snakes, demons and all things evil from a human standpoint (thus, presumably also candirus) in the Zoroastrian religion, approximately equivalent to, and probably historical ancestor of, the devil in Abrahamic mythology

Paracanthopoma capeta — Portuguese vernacular (probably a combination of capa, cape, and ‑eta, a diminutive suffix) meaning the devil (i.e., an evil fish from a human standpoint)

Paracanthopoma carrapata — feminine declension of carrapato, Portuguese name for bloodsucking ticks in general, alluding to this fish’s hematophagous habits

Paracanthopoma daemon — Latinized form of the Greek daimon, “supernatural entities hierarchically between gods and mortals, including inferior divinities and ghosts of some dead men,” i.e., a demonic fish from a human standpoint

Paracanthopoma irritans — Latin for irritating, taken from the name of the human flea, Pulex irritans, also a hematophagous species

Paracanthopoma malevola — Latin for ill-disposed or inimical, i.e., an unfriendly fish from a human standpoint

Paracanthopoma satanica — derived from the Hebrew verb satan, meaning literally “to oppose” but commonly used to refer to an enemy or the devil (i.e., an unfriendly or evil fish from a human standpoint)

Paracanthopoma truculenta — Latin for harsh, cruel or brutish, alluding to its size, the largest species of this hematophagous genus

Paracanthopoma vampyra — Latinization of the Slavic wampir, a blood-sucking ghost or demon, referring to its hematophagous habits

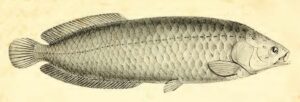

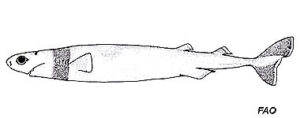

Gyrinocheilus pennocki. From: Fowler, H. W. 1937. Zoological results of the third De Schauensee Siamese Expedition. Part VIII. Fishes obtained in 1936. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia v. 89: 125-264.

9 November

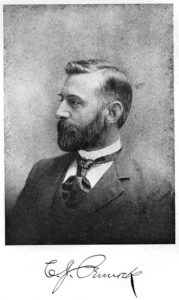

Gyrinocheilus pennocki (Fowler 1937)

American ichthyologist Henry Weed Fowler (1878-1965) had the curious habit of naming fishes from foreign countries after Americans who helped him acquire fishes from the United States. Gyrinocheilus pennocki is one example. Fowler named this algae eater (Gyrinocheilidae) from Thailand in honor of the late Charles J. Pennock (1857-1935) of Kennett Square, Pennsylvania, USA. Pennock, to whom Fowler was indebted for specimens of various North American fishes, was a businessman (insurance, real estate), local politician and Justice of the Peace. He was also a serious bird enthusiast, serving as President of the Delaware Valley Ornithological Club (DVOC), one of the oldest ornithology organizations in the United States.

In May 1913, Pennock’s life took a bizarre, delusional turn. After a DVOC meeting, instead of taking the train home to his wife and family, he disappeared. His family was baffled. He had wandered off once before, explained at the time as memory loss due to “inflammatory rheumatism,” but this time was different. He remained missing for over six years.

Pennock made his way to St. Marks, Florida, shaved his beard, and began a new life under the name of John Williams. He worked as a bookkeeper for a local fishing company and even became a prominent citizen, serving as County Commissioner and a notary public. He also continued to collect birds and bird eggs, and to publish articles on his ornithological studies, all under his new name. His ornithological work led to his discovery. In September 1919, “Williams” submitted an article to “The Auk” (now called “Ornithology”), the official publication of the American Ornithological Association. The editor, Witmer Stone, had known Pennock and edited his earlier articles. Based on handwriting and writing style, Stone thought that John Williams and Charles Pennock could be the same person but dismissed the idea as ridiculous. Two months later, Stone mentioned the possibility to Richard J. Phillips, Pennock’s brother-in-law. In December, Phillips traveled to St. Marks, Florida, found Pennock, and persuaded him to return home, which he did, wearing the same suit he had worn the day he disappeared. Pennock reunited with this wife, resumed activities with the Delaware Valley Ornithological Club and some of his business interests.

Pennock made his way to St. Marks, Florida, shaved his beard, and began a new life under the name of John Williams. He worked as a bookkeeper for a local fishing company and even became a prominent citizen, serving as County Commissioner and a notary public. He also continued to collect birds and bird eggs, and to publish articles on his ornithological studies, all under his new name. His ornithological work led to his discovery. In September 1919, “Williams” submitted an article to “The Auk” (now called “Ornithology”), the official publication of the American Ornithological Association. The editor, Witmer Stone, had known Pennock and edited his earlier articles. Based on handwriting and writing style, Stone thought that John Williams and Charles Pennock could be the same person but dismissed the idea as ridiculous. Two months later, Stone mentioned the possibility to Richard J. Phillips, Pennock’s brother-in-law. In December, Phillips traveled to St. Marks, Florida, found Pennock, and persuaded him to return home, which he did, wearing the same suit he had worn the day he disappeared. Pennock reunited with this wife, resumed activities with the Delaware Valley Ornithological Club and some of his business interests.

The New York Times (1 Jan. 1920) reported on Pennock’s return: “Suffering from a nervous disease, he had become victim of a delusion that he had to leave every one and bury himself. He was discovered … buried in the forests of Florida where his only solace in his self-enforced exile was the companionship of the birds.”

Pennock died from a heart attack at his home in Kennett Square, Pennsylvania, on 20 August 1935.

When Pennock disappeared, The New York Times (20 May 1913) published a brief “missing persons” notice that contained a rather stunning statement. According to the Times, “Twenty-five men, several of them leaders in business circles in Philadelphia and its vicinity, have disappeared within the past few months, and in only a few cases have they been found.”

Was there a sinister or conspiratorial reason for Pennock’s disappearance?

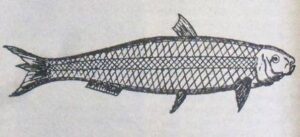

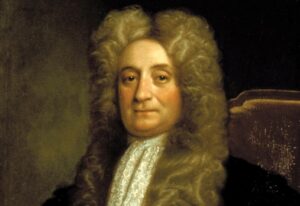

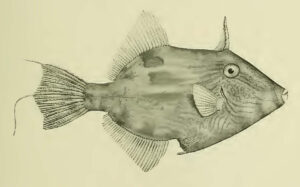

Salviani’s illustration of Phycis phycis, which he called Callarias. From: Salviani, H. 1558. Aquatilium animalium historiae liber primus, cum eorumdem formis, aere excusis. Rome. viii + 256 pp.

2 November

Phycis phycis – a double misnomer

Written with Holger Funk, in memory of Hippolito Salviani, a pioneering ichthyologist who died 450 years ago

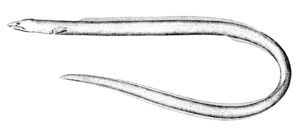

The Forkbeard Phycis phycis (Linnaeus 1766) is a nocturnal, deeper-water cod-like fish (family Phycidae, order Gadiformes) from the Mediterranean, the Azores, and the Northeast Atlantic from Morocco to Cape Verde. Its scientific name is a Latinization of the Greek φῦκος (phū́kos), meaning seaweed. The ancient Greeks associated the phycis with wrasses (Labridae), which live amidst seaweed and build their nests from it. Wrasses were therefore rightly called seaweed fishes. Phycis phycis, on the other hand, have nothing to do with seaweed, and so its name is biologically incorrect.

How did this double misnomer come about?

The first naturalist to accurately describe and illustrate the Forkbeard (long before Linnaeus gave it its official name) was the Italian Hippolito Salviani (1514–1572) in his work Aquatilium animalium historiae of 1558. Salviani not only introduced the species to science, he also recognized two essential points: 1) that in Rome, where he lived, a kind of cod was popularly called Fico, a name linguistically and etymologically unrelated to the Phycis of antiquity (Fico is a transfer from the fruit fig, Italian fico, Latin ficus, since the flesh of both is said to be similarly soft); and 2) Salviani recognized that the fish was not a wrasse but a cod. He therefore named the fish Callarias, a term applied to cods since ancient times. The name Phycis, by contrast, Salviani reserved for Serranus cabrilla or Comber, which in fact also lives in seaweed, specifically in Neptune grass or Mediterranean tapeweed (Posidonia oceanica).

In the 1720s, Peter Artedi trawled through ancient and Renaissance texts for his systematic worldwide revision of fishes. He briefly reported (Ichthyologia, 1738, pars IV: Synonymia, p. 111) on Salviani’s important findings about Callarias, but he seems to have misread Salviani’s rather opaque, hyperscholarly Latin-Greek prose. In so doing, he erroneously believed that three fishes mentioned in Salviani’s account — the Phycis of antiquity (a wrasse), “Tenca marina” (the Roman equivalent of Phycis), and Callarias — were all the same species. Although Artedi agreed with Salviani that the fish was a cod, he selected the seaweed/wrasse name Phycis to represent it.

The name has stuck.

After Artedi’s accidental death in 1735, his friend and literary executor Carl Linnaeus edited and published Artedi’s unpublished manuscripts in 1738. When Linnaeus later dealt with the Forkbeard Phycis himself (Systema naturae, 12th edition, vol. 1, Stockholm 1766, p. 442), using his binominal (genus-species) naming system, he called it Blennius phycis, borrowing Artedi’s name for the genus as the name for the species. Since Linnaeus believed the Forkbeard is a blenny, he placed it in the genus Blennius.

When Johann Julius Walbaum (1724–1799) updated and republished Artedi’s Ichthyologia in 1792, he made Artedi’s pre-Linnaean names (including Phycis) nomenclaturally available for future taxonomists. In 1933, Italian ichthyologist Umberto D’Ancona realized that Blennius phycis — not a blenny — needed a new generic name. Since Walbaum’s account of Artedi’s Phycis was the oldest available name, he unavoidably created the double misnomer Phycis phycis.

According to the ICZN rules, misleading or false names do not need to be revised or changed as long as they were formed correctly. Such names have been covered in previous NOTWs (e.g., Xyrauchen texanus, wrong locality, 1 August 2018, or Micropterus nigricans, wrong coloration, 26 October 2022). Tautonyms are an escalation of such factually incorrect names but are just as unchallengeable by decree (ICZN Art. 23.3.7): “The availability of a name is not affected by inappropriateness or tautonymy.”

The Forkbeard does not live among seaweed. Instead, it prefers hard sand-and-mud substrates near rocks. But because of its misleading name, misinformation about its habitat persists to this day. According to FishBase, the name is “Taken from Greek, phykon = seaweed; because of the habits of this fish that lives hidden among them …”.

Color plate accompanying Cuvier’s description of Huro (now Micropterus) nigricans. Unfortunately, it’s a poor rendering that scarcely resembles a Largemouth Bass.

26 October

Micropterus nigricans (Cuvier 1828)

Black basses (genus Micropterus, family Centrarchidae) are the most popular recreational gamefishes in North America (and introduced for this purpose around the world). But I’ve always wondered about the common name “black bass.” Why are they called “black” when their predominant color is dark olive or bronze? Yes, they may have dark or black markings on their bodies, but they do not seem black enough to justify the adjective.

Thanks to a recent revision of Micropterus (more on that below), I believe I found the answer in the original description of a newly reinstated species: Micropterus nigricans, proposed (as Huro nigricans) by the famous French anatomist Georges Cuvier in 1828.

The Latin adjective “nigricans” means swarthy or blackish. But Cuvier did not describe a swarthy or blackish fish. He wrote (translated from the French):

The color of this fish, which we have only seen dried, seems to approach that of the carp. Its back is a greenish-brown, fading at the sides, and passing under the belly to a silvery-yellowish-white. A grayish line follows the middle of each longitudinal row of scales.

So why the “blackish” name?

Cuvier described the fish from a specimen from Lake Huron, one of the five Great Lakes of North America, shared on the north and east by the Canadian province of Ontario and on the south and west by the U.S. state of Michigan. According to Cuvier (again translated from the French):

The English [speakers] of the vicinity of this lake call it black-bass or black perch, because it indeed resembles rather in habit [i.e., shape] and tints another fish that bears the same name in the United States, and which we will describe further in our centroprist genus to which it belongs.

The “centroprist” species is the Black Sea Bass, Centropristis striata (Serranidae), which is indeed black.

Cuvier ended his description with an etymological sign-off: “We will give this species the epithet it bears in its native country, Huro nigricans” (Huro referring to Lake Huron).

I now have the answer I sought: Black basses are called black basses because people in early 19th-century America thought Micropterus nigricans looked like a sea bass that occurs in the western Atlantic Ocean over 1100 km away.

I should note for the sake of completeness that Dwight A. Webster, a fisheries professor at Cornell University, proposed a different explanation 42 years ago. Writing in the March-April 1980 issue of Fisheries magazine, Webster suggested that the name “black bass” refers to the resemblance of the Largemouth Bass to a different Atlantic species, the Tautog Tautoga onitis (Labridae), also known as “blackfish.” While the two fishes do share a superficial resemblance, and it’s feasible that early Americans conflated all three species (bass, sea bass, tautog) under one vernacular, Cuvier’s explanation, explicitly linking Micropterus nigricans to Centropristis striata, is impossible to dismiss.

As mentioned above, Micropterus nigricans is a newly reinstated species. According to a recent genomic analysis by Kim et al. (2022), the scientific names M. salmoides and M. floridanus have been incorrectly applied to Largemouth Bass and Florida Bass, respectively, over the past 75 years. Based on their analysis, Kim et al. reveal that M. salmoides is the accurate and valid scientific name for the Florida Bass, whereas M. floridanus, traditionally applied to that species, is a junior synonym of M. salmoides. The oldest available scientific name for the Largemouth Bass is therefore M. nigricans, hence the elevation of that long-forgotten name.

M. nigricans is not the first species of the genus whose scientific name reflects a local name that compares the fish to an unrelated species. In 1802, Lacepède named M. salmoides, meaning “salmon-like,” based on an illustration of a specimen collected near Charleston, South Carolina. Lacepède selected the epithet because the specimen was labeled “trout,” its local name in Charleston.

19 October

From α to ω in the names of fishes (part 3)

Concluding our “miniseries” on fish names inspired by letters of the Greek alphabet …

Betta pi (from seriouslyfish.com).

Pi Π π

Perhaps the most famous letter of the Greek alphabet is the 16th, pi. Most of us know it as the ratio of a circle’s circumference to its diameter, approximately equal to 3.14159. But the distinctive shape of the letter has inspired two fish names.

In 1978, Richard P. Vari of the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C., described Protocheirodon pi, a characid from the Amazon basin on Bolivia, Peru and Columbia. He named it for the π-like shape of its swim bladder.

Twenty years later, Heok Hui Tan (National University of Singapore) described the osphronemid Betta pi from the Narathiwat Province of Thailand. He named it for the π-like marking on its throat.

Rho Ρ ρ

I am bending the rules with this one. Chaenopsis resh Robins & Randall 1965, a pikeblenny (Chaenopsidae) from the southern Caribbean Sea, is not named for the Greek letter rho. It’s named for the Hebrew letter resh ( ר), the form of which characterizes this species’ diagnostic postocular mark. I include it because the Phoenician letter Rēsh gave rise to both the Greek and Hebrew forms of the letter.

Sigma Σ σ (or ς when used at the end of a letter-case word)

The Latin letter “S” is derived from the Greek letter Σ. That explains the S-shaped reference in these two names:

Sigmistes Rutter 1898 — This genus of Pacific Ocean sculpins (Psychrolutidae) is named for the strongly arched lateral line of S. caulias, creating an S-like shape. The second half of the name, –istes, is a Latin suffix that serves as a signifying agent, i.e., “one that is shaped like an S.”

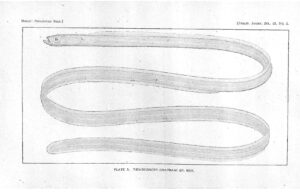

Lycodes sigmatoides Lindberg & Krasyukova 1975 — This eelpout (Zoarcidae) from the Sea of Japan and Sea of Okhotsk is named for the S-shaped spots on back. The second half of the name, –oides, is an adjectival suffix meaning “having the form of.” In other words, “S-shaped.”

Lycodes sigmatoides, incorrectly captioned as Lycodes sigmatus. From: Lindberg, G. U. and Z. V. Krasyukova. 1975. Fishes of the Sea of Japan and adjacent territories of the Okhotsk and Yellow Sea. Part 4. Teleostomi. XXIX. Perciformes. 2. Blennioidei – 13. Gobioidei. (CXLV. Fam. Anarhichadidae–CLXXV. Fam. Periophthalmidae). Izdateljestvo Nauka, Leningradskoie Otdeleie, Leningrad. 1-463.

Just as the letter π serves as a mathematical symbol, so does Σ. In modern mathematics Σ means “sum total.” Encrasicholina sigma Hata & Motomura 2020, an anchovy (Engraulidae) from Indonesia, is named for the symbol Σ in reference to the sum total of its gill raker numbers (upper and lower series, 37–42) on the first gill arch, the “major diagnostic feature” of this species.

Tau Τ τ

The Oyster Toadfish Opsanus tau (Linnaeus 1766), a common nearshore fish from Maine to Florida, is named for how the bones on its head, when dried, show a T-shaped figure.

Upsilon (or Ypsilon) ϒ υ

The 20th letter of the Greek alphabet is transliterated in the traditional Latin style as “y” or in the modern style as “u.” As such, the name of the letter is spelled two ways: upsilon and ypsilon. Fishes have been named both ways. For example:

Gymnothorax ypsilon Hatooka & Randall 1992, a moray eel (Muraenidae) from Japan, Hawaii and New Zealand, is named for how the bars on its body branch dorsally to form a Y-shape. Compare this with …

Oman ypsilon Springer 1985 — This blenny from the Persian Gulf is named for the dark U-shaped marking on the anterodorsal surface of its head.

Several other fish names (six by my count) are named for Y-shaped bars, lines, head ridges, photophores, and other externally visible features. This one is named for an internal feature that cannot be seen by the naked eye:

The last captive-bred male Megupsilon aporus photographed in the laboratory of Christopher Martin at UC Berkeley.

Megupsilon Miller & Walters 1972 is a monotypic genus of pupfshes (Cyprinodontidae) known only from a spring in Nuevo Léon, Mexico. Its name is a combination of mega, meaning large, and upsilon, referring to the exceptionally large Y chromosome in males. The sole species, Megupsilon aporus, went extinct in the wild in 1994. The last surviving specimen in captivity died in 2014.

Phi Φ φ

As far as I can tell, no fishes are named for the Greek letter phi (pronounced “p” as in “pot”).

Chi Χ χ

This, the 22nd Greek letter, is not to be confused with the 14th letter, Xi Ξ ξ. The confusion lies in the fact that Xi is pronounced “ks” as in “fox,” whereas Chi (pronounced “k” as in “cat”) looks like the letter “x.” (See previous post about Cynodonichthys xi.) Be that as it may, the authors of Xenisthmus chi Gill & Hoese 2004 got it right: This collared wiggler (Xenisthmidae) from the Timor Sea of Western Australia is named for the X-shaped markings on its body.

Psi Ψ ψ

As far as I can tell, no fishes are named for the Greek letter psi (pronounced “ps” as in “lapse”).

Omega Ω ω

The distinctive Ω shape of omega is likely conveyed in the name of the puffer genus Omegophora (“omega bearer”), coined by Gilbert Percy Whitley in 1934. Whitley didn’t explain the name but it almost certainly refers to the narrow, black, Ω-shaped ring around the pectoral-fin base of its type species, O. armilla.

The fact that omega is the last letter of the Greek alphabet is reflected in these two names:

Aphyosemion omega (Sonnenberg 2007) — This non-annual killifish from Cameroon is in the same subgenus (Chromaphyosemion) as A. alpha (mentioned in part one of this series). Sonnenberg chose the name with regard to A. alpha in the sense of alpha (the beginning) and omega (the end), referring to the relative (phylogenetic) position of both species, with C. alpha as the basal species and C. omega as a more derived species, the result of a recent radiation.

Just as in Betta pi (mentioned above), Betta omega Tan & Ahmad 2018, from peninsular Malaysia, is named for the letter-like marking on its throat, in this case resembling Ω instead of π. The name has a sadder meaning as well. The “last members” of this species, the authors wrote, are quickly disappearing in the wild.

12 October

From α to ω in the names of fishes (part 2)

Continuing our survey of fish names inspired by letters of the Greek alphabet …

Zeta Ζ ζ

Although zeta is the sixth letter of the Greek alphabet, it is the 26th and final letter of the modern English alphabet. For this reason the letter Z is often associated with things that are last or final. As in this fish’s name:

Oxyurichthys zeta, live specimen at Lovina Beach, Bali, Indonesia. Photograph by Ole Brett. From: Pezold, F. L. and H. K. Larson. 2015. A revision of the fish genus Oxyurichthys (Gobioidei: Gobiidae) with descriptions of four new species. Zootaxa 3988 (no. 1): 1-95.

Oxyurichthys zeta Pezold & Larson 2015 is a goby that hovers over the substrate in marine waters (12-38 m deep) off Japan, Palau, Bali, Flores, Papua New Guinea and Solomon Islands. The authors named it zeta because it’s the last of 20 species included in their revision of Oxyurichthys — although, they write, “it is unlikely to be the last species described for this genus.” (Indeed, one additional species has been described so far.)

Astronesthes zetgibbsi Parin & Borodulina 1997 is a snaggletooth (Stomiidae) known from 80 meters deep in the southeastern Pacific. The “zet” part of the name refers to the letter Z. The second part of the name honors Robert H. Gibbs, Jr. (1929-1988), “one of the most authoritative researchers” (translation) of the family and other stomiiform fishes. Gibbs called this taxon “species Z” in his unpublished materials.

Eta Η η

As far as I can tell, no currently valid fish taxa are named for Greek letter #7, eta.

Diaphus zeta with photophores. Photo courtesy of Jeff Drazen. From: Exploring Our Fluid Earth

Theta Θ θ

Diaphus theta Eigenmann & Eigenmann 1890 is the type species of the speciose (81 species) lanternfish genus Diaphus. Lanternfishes, as the common name suggests, are bioluminescent. Both generic and trivial names of D. theta refer to how most or all of its photophores are divided by a horizontal cross septum of black pigment: dia– means divided and phos means light, resembling the divided “0” shape of the Greek letter θ, theta.

Iota Ι ι

Iota is the smallest letter of the Greek alphabet. Because of this, iota is also a noun that means “an extremely small amount.” Ichthyologists have used “iota” several times for fishes that are small. Here are two examples:

Iotichthys Jordan & Evermann 1896 — a monotypic minnow genus endemic to Utah (USA). Iotichthys phlegethontis, the Least Chub, reaches a maximum size of less than 6.4 cm. (I assume you know what ichthys means.)

Eviota Jenkins 1903 — a diverse (128 species and counting) genus of gobies. The Greek prefix eu– (Latinized to ev– for euphony) means good, well or very, i.e., very small. Jenkins coined the name for E. epiphanes, which, at 1.0-1.9 cm in length, he believed was the “smallest vertebrate that has up to this time been described.”

The Guyanese tetra Hemigrammus iota Durbin 1909 may be small but that’s not why it was given its name. Iota is the precursor to both “I” and “J” in the Latin alphabet. Marion Durbin (1887-1972, also known by her married name, Marion Ellis) named it for the black I-shaped bar on its caudal peduncle.

Priolepis kappa, live specimen at Bali, Indonesia. Photo by John E. Randall. Courtesy: FishBase.

Kappa Κ κ

Priolepis kappa Winterbottom & Burridge 1993 is a goby found in the Indo-West Pacific from the Comoro Islands to Indonesia, Philippines and to Queensland, Australia. It’s named for the Greek letter kappa, referring to the stylized “k” formed by its postocular and ocular bars.

Lambda Λ λ

Leptojulis lambdastigma Randall & Ferraris 1981 is a wrasse (Labridae) from the eastern Indian and western Pacific oceans from the Andaman Islands, east to Philippines and north to Taiwan. It’s named for the conspicuous Λ-shaped mark (stigma) on its nape.

Leptojulis lambdastigma, holotype, male. Photo by Carl Ferraris. From: Randall, J. E. and C. J. Ferraris, Jr. 1981. A revision of the Indo-Pacific labrid fish genus Leptojulis with descriptions of two new species. Revue française d’Aquariologie Herpétologie v. 8 (no. 3): 89-96.

I do not see any fishes named for the next two letters of the Greek alphabet … Mu Μ μ

Nu Ν ν.

Xi Ξ ξ

Cynodonichthys xi (Vermeulen 2013) — This rivulid killifish from Colombia is named for the 14th letter of the Greek alphabet, referring to the unique x-markings on the sides of males. “Xi” is easily confused with the 22nd letter of the Greek alphabet, “chi” (pronounced “k” as in cat), because “chi” is written as “x” in Latin. So maybe Cynodonichthys xi should have been named Cynodonichthys chi?

Omicron Ο ο

I do not see any fishes named for omicron, but I’m sure you recognize the letter as the name of a highly contagious and now predominant variant of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. The World Health Organization assigns a Greek letter to each variant in the order in which they appear. Omicron was the 13th variant but WHO skipped over the 13th (Nu) and 14th (Xi) letters to avoid confusion with the English word “new” and the common Chinese last name “Xi.”

Next week we’ll conclude this series beginning with the ever-popular π.

5 October

From α to ω in the names of fishes (part 1)

Taxonomists draw inspiration from many sources in the zoological names they coin. Here are some of the fish names inspired by letters of the Greek alphabet.

Alpha Α α

Aphyosemion alpha Huber 1998 is a non-annual killifish from Gabon. It’s named for the red α-shaped dots on the sides of males.

Otopharynx alpha, photograph by George Turner, courtesy Michael Oliver.

Otopharynx alpha Oliver 2018 is a cichlid from Lake Malaŵi, Africa. Its name refers to its suprapectoral spot and posterior stripe, which suggest a dot and dash (*-), an “A” in International Morse Code.

Chromis alpha Randall 1988 is an Indo-Pacific damselfish that occurs from Christmas Island to the Society Islands, north to the Mariana Islands, and south to New Caledonia through Micronesia. Its name has a double meaning. It alludes to the Greek alphós (ἀλφός), meaning white-spotted (as from leprosy), referring to the pale spots on its head and body. The name also refers to the first letter of alphabet, referring to its designation as Chromis sp. “A” by Gerald R. Allen, who first diagnosed and illustrated this species in 1975

Beta Β β

Schultzea beta. From: Longley, W. H. and S. F. Hildebrand. 1940. New genera and species of fishes from Tortugas, Florida. Papers Tortugas Laboratory, Carnegie Institution of Washington v. 32: 223-285, Pl. 1.

Schultzea beta (Hildebrand 1940) is a small, schooling sea bass (Serranidae) from deeper waters around coral reefs in the Caribbean Sea and off the Florida Keys. It’s named for the second letter of the alphabet because it’s the second species from Tortugas (Florida, USA) of “uncertain generic affinities” included in Hildebrand’s paper (co-authored with William H. Longley).

Opsanus beta (Goode & Bean 1880) is an oyster toadfish that occurs in the Gulf of Mexico and western Atlantic off Florida and the Bahamas. Albert Günther described it as a southern form of Opsanus tau (itself named after a Greek letter; more in a future installment) in 1861, using the Greek “α” for the northern form and the Greek “β” for this one. When Goode & Bean decided that the form warranted its own name, they spelled out Günther’s “β.”

Gamma Γ γ

Knodus gamma Géry 1972 — French ichthyologist Jacques Géry did not explain why he selected this name for a characin from the western Amazon basin of Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and Bolivia. But the context is clear. Géry was continuing Carl Eigenmann’s tradition of naming closely related and similar taxa after Greek letters (e.g., Bryconamericus alpha and B. beta). So Géry named the third such species after the third letter of the Greek alphabet, and the fourth species, K. delta, after the fourth. Speaking of delta …

Delta Δ δ

The triangular shape of the upper-case delta (Δ) has inspired several names.

Deltistes luxatus, courtesy The Oregon Conservation Strategy.

Gill (1863) named the goby genus Deltentosteus (osteus = bone) for the Δ-like shape of the lower pharyngeal bones of D. quadrimaculatus.

Alvin Seale proposed Deltistes as a monotypic genus for the federally endangered Lost River Sucker D. luxatus of northern California and Orgeon (USA). He named it for its Δ-shaped gill rakers.

The husband-and-wife team of Eigenmann & Eigenmann (1889) named the catfish (Loricariidae) genus Delturus for the tail (urus) of Delturus parahybae, described as flat above, trenchant below, and Δ-shaped in cross section.

Chaenopsis deltarrhis Böhlke 1957, a pikeblenny (Chaenopsidae) from the eastern Pacific of Costa Rica south to Colombia, is named for the triangular shape of its snout (rhis) when viewed from above

The near-triangular shape of its vomerine tooth patch inspired the name of Ostichthys delta Randall, Shimizu & Yamakawa 1982, a squirrelfish from the Indo-West Pacific of Réunion (western Mascarenes), Comoros and Samoa.

The name of Pycnochromis delta (Randall 1988), a wide-ranging damselfish from the eastern Indian Ocean and western Pacific, harkens back to Chromis sp. “A” mentioned above. Gerald R. Allen called this one Chromis sp. “D.”

Epsilon Ε ε

As far as I can tell, no currently valid fish taxa are named for Greek letter #5, epsilon. Bummer.

Next week we’ll explore zeta, theta, iota in part 2 of our piscine alphabetarium.

28 September

Gerald R. Smith (1935-2022)

Soon after I posted last week’s tribute to the late Victor G. Springer, I learned that another ichthyological luminary had passed. Gerald R. Smith, Emeritus Curator of Fishes for the Museum of Zoology and Emeritus Curator of Lower Vertebrates for the Museum of Paleontology at the University of Michigan, died peacefully at home, surrounded by family, at the age of 87.

Dr. Smith — Jerry to family, friends and colleagues — was born March 20, 1935 in Los Angeles, California, and was raised in Salt Lake City, Utah, where he earned a B.S. (1957) and M.S. (1959) at the University of Utah. In 1965, he completed his Ph.D. in Zoology at the University of Michigan, studying under the legendary Robert Rush Miller (see 22 April 2015 NOTW).

Dr. Smith’s primary field of study was the evolution of North American freshwater fishes, with particular interests in Cenozoic fossils, the calibration of rates of evolution, speciation, biogeography, and conservation. His primary field work was in the Great Basin and on the Snake River Plain. In western Idaho and eastern Oregon, living fishes in the Snake River are surrounded by sediments bearing the fossils of their ancestors’ sedimentary sequences from 2-10 million years old, providing a rich laboratory for the study of evolution. Dr. Smith was also an authority in the identification and ecology of fishes of the Laurentian Great Lakes. He published a revised edition of Hubbs & Lagler’s classic Fishes of the Great Lakes Region in 2004.

While not primarily a taxonomist, Dr. Smith did describe or co-describe four fish taxa, all suckers (Catostomidae) of the American West:

Catostomus columbianus hubbsi Smith 1966, a subspecies of Bridgelip Sucker from the Wood River drainage of Blaine County, Idaho — in honor of Carl L. Hubbs (1894-1979), for his work on western American fishes, his leadership in ichthyology, and for collecting the holotype.

Chasmistes liorus mictus Miller & Smith 1981, the June Sucker, endemic to Utah Lake, Wasatch County, Utah — name derived from the Greek miktos, mixed or blended, believed to be a hybrid between C. liorus and Catostomus ardens (a hypothesis since challenged by another researcher).

Chasmistes muriei Miller & Smith 1981, the extinct Snake River Sucker of Wyoming — in honor of wildlife biologist Olaus J. Murie (1889-1963), who collected the only known specimen in 1927.

Paratype of Pantosteus bondi, 118 SL, from the South Santiam River at Lebanon, Willamette drainage, Linn Co., Oregon. Illustrated by John Megahan. From: Smith, G. R., J. D. Stewart and N. E. Carpenter. 2013. Fossil and recent mountain suckers, Pantosteus, and significance of introgression in catostomin fishes of the western United States. Occasional Papers of the Museum of Zoology University of Michigan No. 743: 1-59.

Pantosteus bondi (Smith, Stewart & Carpenter 2013), the Cordilleran Sucker of the Columbia and Lower Snake River drainages of Oregon — in honor of the late Carl E. Bond (1920-2007), Oregon State University, for his many contributions to the science, conservation, and management of northwestern North American fishes.

Dr. Smith described or co-described several fossil suckers as well.

On a personal note, news of Dr. Smith’s death was especially sad for me since my wife and I had spent a weekend with him during the annual convention of the North American Native Fishes Association (NANFA) in Ann Arbor, Michigan, in 2002. Dr. Smith was complimentary of my work as editor of American Currents, NANFA’s quarterly publication. In fact, he had a copy on display in the rotunda of the University of Michigan Museum of Zoology (UMMZ).

Dr. Smith invited us to poke around the UMMZ fish collection, the fourth largest (among eight) International Ichthyological Resource Center in North America. It was a treat for me to see the very same specimens that Carl Hubbs and Robert Rush Miller collected during their famous expeditions to the American West (see 22 April 2015 NOTW). I got to hold in my hands the all-but-forgotten Las Vegas dace (Rhinichthys deaconi, see 4 March 2015 NOTW), knowing that this fish went extinct for the benefit of Las Vegas fountains and golf courses. Many specimen jars were adorned with the red “extinct” label and I examined them all, wondering how many others would soon be joining their ranks.

After touring the stacks, Dr. Smith put us to work. The University had developed a beta version of an on-line database of Great Lakes flora and fauna and wanted us to test the fish portion of it while the site’s designers looked on. We were more than happy to comply, especially since Dr. Smith treated us to beer, pop and assorted snack goodies.

Later that same weekend, while snorkeling and collecting fishes in a Michigan stream, my wife and I got separated from our party. Dr. Smith graciously drove us back to our hotel in his pick-up truck, going miles out of his way. He talked with obvious joy about his farm and his passion for sustainable agriculture. Earlier in the day I snapped the photo shown here: Dr. Smith explaining the subtle differences between Blacknose (Notropis heterolepis) and Blackchin Shiner (N. heterodon) to a seemingly astonished Nick Zarlinga of the Cleveland Metroparks Zoo.

Later that same weekend, while snorkeling and collecting fishes in a Michigan stream, my wife and I got separated from our party. Dr. Smith graciously drove us back to our hotel in his pick-up truck, going miles out of his way. He talked with obvious joy about his farm and his passion for sustainable agriculture. Earlier in the day I snapped the photo shown here: Dr. Smith explaining the subtle differences between Blacknose (Notropis heterolepis) and Blackchin Shiner (N. heterodon) to a seemingly astonished Nick Zarlinga of the Cleveland Metroparks Zoo.

Tributes from others say much the same thing. Gerald R. Smith was a superb scientist, an excellent teacher always willing to share his knowledge, a steward of the Earth, and a soft-spoken, kind and generous human being.

21 September

21 September

Victor G. Springer (1928-2022)

Victor G. Springer, Curator Emeritus of Fishes at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History, passed away peacefully on Sunday, September 18, at the age of 94. When I heard this news, I dropped the NOTW I had been writing and prepared this one instead. It took me close to an hour to comb through ETYFish looking for all the fishes that Springer named and for all the fishes named after him. By my unofficial count:

Springer described or co-described 20 new fish genera considered valid today.

Springer described or co-described 113 new species of fishes considered valid today.

Many of these new taxa are blennies (especially those of the genus Ecsenius) and other blenniiform fishes. But Springer also made valuable contributions to the taxonomy of sharks, gobies, clingfishes (Gobiesocidae), and dottybacks (Pseudochromidae), to name just a few. A long and impressive career.

Even more impressive is the number of taxa named after him. I count 20 currently valid fishes named “springeri” and one named “gruschkai” (after his middle name), ranging from gudgeons (Gobionidae) to flathead (Platycephalidae), with lots of blennies in between. Here is one example:

Pteropsaron springeri, photographed at Dauin, Philippines. Photo by Andrey Ryanskly. Courtesy: FishBase.

Pteropsaron springeri Smith & Johnson 2007, an Indo-Pacific duckbill (Hemerocoetidae) from Negros Island of the Philippines (shown here) — in honor of colleague Victor G. Springer, who first collected this species and recognized it as undescribed, for his “many contributions to our knowledge of Indo-Pacific reef fishes, and his unselfish and steadfast dedication to the growth and well being of the collections and the advancement of ichthyology at the National Museum of Natural History”

Having a species named after you is, of course, a wonderful honor. Having an entire genus named after you is a supreme honor indeed. Springer has two, from the same ichthyologist: Springeratus Shen 1971 (kelp blennies, Clinidae) and Springerichthys Shen 1994 (threefin blennies, Tripterygiidae). Shen clearly admired his colleague.

There’s nothing I can say about Dr. Springer’s storied career that wasn’t already said in this superb retrospective:

Smith, David G. 2005. “Historical Perspectives – Victor Gruschka Springer.” Copeia 2005 (3): 431–439.

It’s behind a paywall but you can read a summary here.

As mentioned in the Copeia article, Dr. Springer not only collected fishes. He collected postage stamps too, specifically those with images of fish or fishing. In 1985, he co-authored a booklet that contained an annotated list of all such stamps that were issued from 1865 through 1992, with all of the species correctly identified. He and his philatelic colleague, the late Maynard S. Raasch (author of a delightful little book on the fishes of Delaware, USA), continued adding to the list through 1998. By the time they finished, the list contained about 10,000 entries.

Collecting, cataloguing, classifying, organizing — these are the joys of a taxonomist’s life. For Victor G. Springer, it must have been a joyful life indeed.

14 September

Bach, Beethoven, Mozart, and the piquitinga herring of Brazil

The name piquitinga — as in Lile piquitinga (Schreiner & Miranda Ribeiro 1903), a gizzard shad from the Atlantic drainages of Costa Rica, Venezuela and Brazil — is not crucial to this story. But it’s too good a story not to tell. Whether it’s searching for the meaning of a name, or in this case a 17th-century painting of a fish, we can relate to the dogged pursuit of historical minutiae this story exemplifies, and the larger discoveries that can happen as a result.

Historia Naturalis Brasiliae, published in 1648, is the first scientific work on the natural history of Brazil. Among the fishes discussed and illustrated is one that author Georg Marcgrave (to use one of the most common spellings of his last name) called “Piquitinga,” presumably its indigenous name. Early taxonomists such as Linnaeus and Cuvier determined that Marcgrave’s description and accompanying woodcut illustration represent a species of anchovy. Over 250 years later, Schreiner & Miranda Ribeiro incorporated Marcgrave’s account into their description of Sardinella piquitinga (now known as Lile piquitinga), a species of herring now in the gizzard shad family (Dorosomatidae).

The woodcut illustration of piquitinga from Historia Naturalis Brasiliae (1648), lacking diagnostic detail.

Peter J. P. Whitehead (1930–1993) of the British Museum (Natural History), an expert in clupeoid fishes (herrings, anchovies and the like), was not convinced that Marcgrave’s piquitinga had been accurately identified. Marcgrave’s written description was general and vague, and the woodcut illustration (shown here) omitted or distorted important diagnostic features. Whitehead simply wanted to know: Was piquitinga a herring or an anchovy?

Whitehead knew that the woodcuts in Historia Naturalis Brasiliae were based on paintings and, as such, likely contained more accurate and realistic details that might make a positive ID possible. Macrgrave’s original paintings had been deposited at Preussische Staatsbibliothek, the Prussian State Library in Berlin. Librarians told Whitehead that the paintings had been lost during World War II.

It was 1973. The Soviet Union controlled eastern Europe. The libraries and archives Whitehead wanted to visit were on the eastern side of the Berlin wall. Access was difficult if not impossible. Undaunted, Whitehead pushed on. The search, as he described it, “took on something of an obsession.”

Whitehead soon learned that Marcgrave’s paintings had been evacuated to Silesia (a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland) to protect them from Allied bombs. Rumors swirled that the paintings had been destroyed in a fire. A year later Whitehead received word from a Benedictine monk at a small monastery in Grüssau (now Krzeszów), Poland, where the paintings had been hidden. They had not been burned in a fire, the monk said, but that they had been removed by Army trucks in 1946, their whereabouts unknown.

“I was now more determined than ever to track them down,” Whitehead later wrote.

At this point, Whitehead discovered that the collection at Grüssau also contained some of the Berlin library’s musical treasures — the original manuscript scores to Mozart’s “Magic Flute” opera and “Jupiter” symphony, Beethoven’s 7th, 8th and 9th symphonies, Mendelssohn’s violin concerto and “Midsummer Night’s Dream” overture, numerous Bach cantatas, and hundreds of other scores. Like Marcgrave’s paintings, they were taken to Grüssau in 1941, presumably in the same wooden crate, to escape the ravages of the war and had not been seen since.

Whitehead called this development a “considerable stroke of luck” because, he said, it was easier to interest people in looking for lost musical treasures than for an obscure painting of an obscure Brazilian fish.

Whitehead enlisted the help of UNESCO and the British Embassy in Warsaw. He asked the Polish Ministry of Culture to investigate and they did, claiming to have searched every Polish library but finding nothing. And, whenever he could, Whitehead called on musicologists and classical music fans to send him leads, news of rumors, clues, any scrap of information that might prove useful. Someone suggested that he contact Prof. Jan Bialostowki, “Poland’s premier art historian.” Whitehead sent him a form letter asking for his help. Some months later, in March 1977, he received a reply.

The “problem of the lost manuscripts has been cleared up,” Bialostowki calmly announced. They were found at the Jagiellonian Library in Krakow.

The long-lost oil painting upon which the woodcut was based.

Over two years later, in September 1979, Whitehead visited the Jagiellonian Library. A librarian wheeled in a trolley bearing seven large volumes. Lifting one of the volumes, the librarian opened it at a marked page: “There!” he said. “There is your piquitinga!”

The painting (shown here) erased all doubts. It was indeed the small herring Lile piquitinga.

Etymological footnote: The genus name Lile is a bit odd in that it’s an Indian (India) name for fishes from North and South America. The name was proposed by Jordan & Evermann in 1896 as a subgenus of Sardinella. Jordan & Evermann said the name derived from matt-lile, a local Tamil language name for Clupea lile (originally Meletta lile Valenciennes 1847) from Pondicherry (now Puducherry), India. Even though two oceans and continents separated the two fishes, Jordan & Evermann believed that Clupea lile (now a junior synonym of Escualosa thoracata Valenciennes 1847) and Sardinella stolifera, the Striped Herring from Mazatlan, Mexico, were closely related and belonged in the same subgenus. They selected the older name Lile to convey this relationship, but they designated the newer species, S. stolifera, as the representative type of the new subgenus (now a full genus). When future taxonomists realized Clupea lile and Escualosa thoracata were the same species, they removed the Indian species that inspired the Lile name, leaving four species that occur nowhere near India — the eastern Pacific Lile stolifera, L. gracilis and L. nigrofasciata, and the southwestern Atlantic L. piquitinga — with an Indian name.

7 September

Dirty, filthy names

You may want to wash your hands after perusing these names.

Callogobius illotus (Herre 1927) — The specific epithet of this marine goby (Gobiidae) from the Philippines is Latin for “unwashed” or “dirty.” It refers to the dark or blackish papillae on the goby’s head, which Herre described as “giving the appearance of adhering dirt or trash.”