NAMES OF THE WEEK from: 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2021 2022 2023 2024 2025

30 December

The meteorite, the museum, the fire, and the catfish

The Bendegó meteorite at Museu Nacional (before the fire).

The Bendegó meteorite is the second-largest meteorite found in Brazil. It was discovered in 1784 by a boy who was grazing cattle on a farm near the present town of Monte Santo in Bahia State. Based on the four-inch layer of oxidation upon which it rested, it had crashed to Earth thousands of years prior. Moving it was difficult due to its weight (5,360 kg). It fell off a cart, down a hill, and into a dry stream bed 180 meters away from where it was found. It remained there until 1888, when it was recovered and brought to the Museu Nacional — the National Museum of Brazil in Rio de Janeiro — in 1888.

The Museu Nacional, founded in1818) is Brazil’s oldest scientific institution. The main building — the “palace” — was originally the residence of the Portuguese royal family between 1808 and 1821. It was converted for museum use in 1892. Over the decades it amassed a vast collection with more than 20 million natural history and anthropological objects, and a scientific library of over 470,000 volumes and rare works. The collection was the principal research center for Brazilian paleontologists, botanists, anthropologists, archaeologists, ethnologists, and zoologists.

The “palace” was destroyed in a fire on the night of 2 September 2018. Faced with budget cuts — including 90% of its maintenance budget — the museum had fallen into disrepair. Peeling paint, termites and exposed wiring were among its many problems. Critics called it a “firetrap.” And it was. The fire began in the air-conditioning system of the auditorium on the ground floor when an exposed wire came in contact with metal. The museum lacked a sprinkler system and firefighters were hindered by poor water pressure in nearby fire hydrants. To fight the blaze they had to pump water from a nearby lake.

Approximately 92.5% of the museum’s collection was destroyed. (The fish and reptile collections and the herbarium, housed off-site, were not affected.) The building was uninsured. The Bendegó meteorite survived the fire due to its inherent fire resistance.

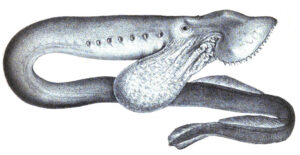

Microcambeva bendego. From: Medieros et al. 2020. A new catfish species of Microcambeva Costa & Bockmann 1994 (Siluriformes: Trichomycteridae) from a coastal basin in Rio de Janeiro State, southeastern Brazil. Zootaxa 4895 (1): 111–123.

Two years before the fire, in August 2016, ichthyologists collected a new species of psammophilous (sand loving), translucent catfish from the rio Guapi-Macacu basin at Guanabara Bay in Rio de Janeiro State, Brazil. Guanabara Bay occurs in the Atlantic Forest, a biodiversity hotspot that extends along the Atlantic Coast of Brazil. Over 85% has been destroyed, threatening many plant and animal species with extinction, including this catfish.

Two weeks ago, on 14 December, the scientific description of this catfish was published in the journal Zootaxa. The authors — Lucas Silva de Medeiros, Cristiano Rangel Moreira, Mário de Pinna and Maia Quiroz Lima — named it Microcambeva bendego, after the meteorite that survived the fire. The authors explained:

Even though part of the building collapsed, the Bendegó remained intact at the main entrance of the museum, where it was seen by the crowd that gathered the day after the fire, becoming a symbol of the resistance of the institution. This is not only an homage to the MNRJ [Museu Nacional, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro], its employees and students, but also an allusion to the resilience of the species herein described in Atlantic Forest basin severely impacted by anthropic actions.

The museum, funded in part by donations from all over the world, is being rebuilt. But nothing can replace the 200 years of work, research, knowledge, and priceless artifacts that were lost.

Enigmapercis reducta, at night near the Port Victoria jetty, South Australia, depth 1 m, January 2013. Source: David Muirhead. Courtesy: https://fishesofaustralia.net.au

23 December

Enigmapercis reducta Whitley 1936

Australian ichthyologist Gilbert Percy Whitley (1903-1975) has been a constant source of material for the “Name of the Week.” He was a master of the enigmatic fish name. Here’s one that is literally enigmatic.

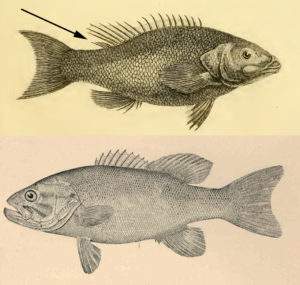

Enigmapercis reducta, the Broad Duckbill, inhabits sandy areas near reefs on the southern half of Australia. It usually lies buried in the sand with only its eyes exposed. Whitley proposed both the genus and the species in 1936, in a very brief account. He followed up with a more detailed description a year later. As per his custom, he did not provide an etymology, but we can reasonably assume that the specific epithet reducta refers to the first anatomical feature he mentioned in his 1937 paper: “A genus of small fishes … in which the spinous dorsal fin is reduced to a couple of small spines connected to the back by membrane and well separated from the soft dorsal fin.” “Reducta” could also mean remote, referring to how the spinous and soft dorsal fins are separated.

The generic name Enigmapercis is just that — enigmatic. The percis, or perch, half of the name may refer to Whitley’s placement of the species in the family Parapercidae (now a synonym of Pinguipedidae in the stargazer order Uranoscopiformes). Today the genus is placed in the signalfish family Hemerocoetidae in the order Pempheriformes. But what does the enigma part mean? What did Whitley find enigmatic about this fish?

In his 1937 paper, Whitley recorded his observations of the holotype, which was still alive when he received it:

“This specimen was brought to the [Australian] Museum alive in a small bottle, together with dredged gravel and shells, which it imitated in coloration to a surprising degree. It lay on the bottom and, to increase the disguise, placed some of the shells on its head and shoulders by flicking with its pectoral fins. It was very hardy, living for a surprising time even in formalin.”

Considering that “enigmatic” can also mean puzzling, perplexing and inexplicable, did Whitley name the species for the inexplicability of a fish disguising itself in a bottle … and then living for a short while in formalin?

Even if Whitley were alive today, he may not divulge the secrets of his names. According to goby taxonomist Helen Larson, Whitley hardly ever gave derivations for his names, “even when asked.”

Cantherhines verecundus, photographed by the great Jack Randall himself. Courtesy: FishBase.

16 December

Cantherhines verecundus Jordan 1925

Far be it from us to challenge the authority of the late John “Jack” Randall (1924-2020), fin for fin, scale for scale, one of the greatest ichthyologists ever. But when it came to explaining the etymology of the specific epithet of Cantherhines verecundus, he was off the mark.

Cantherhines verecundus is a filefish (Tetraodontiformes: Monocanthidae) from the Hawaiian Islands. In his 2011 review of the genus, Randall wrote that “verecundus” means “modest or shy, which is appropriate because this fish is difficult to approach underwater.” No human being has spent more time diving in these waters observing and photographing its fishes. So if Randall says the fish is shy, then it is unquestionably shy. In fact, the fish’s common name is Shy Filefish.

Apparently, however, Randall did not carefully consider Jordan’s original description from 1925. Jordan said the name means “modest,” which, of course, can mean shy or bashful, but other things as well, such as moderate or unassuming. Jordan did not explain why he selected the name. Nor did he mention the fish’s shy or bashful behavior, presumably because he never saw the fish in life. Jordan described the species from seven specimens obtained at a fish market in Honolulu. What’s more, knowing that the fish was shy or bashful when approached by divers would require diving. In 1925, scuba diving had not yet been invented.

What Jordan did describe was the fish’s colors as compared to the closely related and more common C. sandwichiensis, also from Hawaii. Jordan said C. verecundus has a “dull olive” body, “mottled and clouded,” and “paler olive” fins. C. sandwichiensis, however, has a darker body, “usually with small round black spots more or less numerous on head and anterior parts,” with higher dorsal and anal fins that are a “bright orange red in life.”

Based on this comparison, and the fact that Jordan could not have observed this filefish in situ, it seems a pretty good bet that Jordan’s selection of the adjective “verecundus” refers to its modest, less showy coloration compared to C. sandwichiensis.

Sad footnote: Jordan is not the famous American ichthyologist David Starr Jordan (1851-1931), but his son Eric Knight. Six months after Jordan’s description of C. verecundus was published — and just one month after his wedding — he was killed when his car overturned on route to a geological survey in California. Eric Knight Jordan was 22 years old.

References:

Jordan, E. K. 1925. Notes on the fishes of Hawaii, with descriptions of six new species. Proceedings of the United States National Museum v. 66 (no. 2570): 1-43, Pls. 1-2.

Randall, J. E. 2011. Review of the circumtropical monacanthid fish genus Cantherhines, with descriptions of two new species. Indo-Pacific Fishes No. 40: 1-30, Pls. 1-7.

Kyphosus cornelii, at the Abrolhos Islands, Western Australia. Source: Graham Edgar / Reef Life Survey.

9 December

The fish named after a psychopath

I’ve always wondered who is the worst person ever honored in the name of a fish. Our candidates so far have been people honored for their scientific work yet who harbored beliefs considered offensive by today’s standards. Kyphosus cornelii, the Western Buffalo Bream of Western Australia, is an exception. It was named after a very bad person — indeed, an evil person — whose claim to fame are the atrocities he committed.

Jeronimus Cornelisz (also spelled Cornelius, born ca. 1598) was a Dutch apothecary. In 1627, his son died of syphilis, then considered a great scandal, especially for an apothecary. With his reputation damaged and his future business prospects bleak, Cornelisz joined the crew of the Dutch East India Company merchant ship Batavia, which set sail for Java in 1628.

For reasons unclear, Cornelisz and the ship’s skipper, Ariaen Jacobsz, began planning a mutiny. Jacobsz apparently sailed the ship off course, eventually running aground in 1629 on a coral reef at Houtman Abrolhos, a chain of 122 islands in the Indian Ocean off Western Australia. The survivors, some 200 of them, including many women and children, made their way ashore. There was no food, no shelter, and no drinking water. Many survivors did not survive for long. Already desperately sick from scurvy, dehydration quickly took its toll. Jacobsz and the ship’s officers left in the only boat, saying they were in search of water when they were actually fleeing the island on a month-long voyage to Java.

Left on the island, Cornelisz established himself as the leader. They caught fish and collected rain water, but there wasn’t enough to go around. In order to stretch their rations, Cornelisz and his henchmen began murdering the weakest and most vulnerable survivors. Anyone who refused or resisted Cornelisz’ orders was murdered as well. All told, Cornelisz and his henchmen killed between 110 and 124 men, women and children over a two-month period. Their victims were drowned, strangled, hacked to pieces, bludgeoned to death, or had their throats slit. Seven surviving women were forced into sexual slavery.

When a rescue ship arrived, Cornelisz and his men demonstrated that they did not want to be rescued. Instead, they tried to seize the ship, presumably to become pirates and expand their reign of terror throughout the Dutch East Indies. Outmanned and outgunned, they were taken into custody and tortured into confession. Cornelisz was tried on the island, found guilty of mutiny, and hanged along with six of his men. Both of his hands were amputated (per Dutch law at the time) prior to the hanging. Jacobsz reportedly died in a dungeon in Jakarta.

In the 2003 book Batavia’s Graveyard, author Mike Dash makes the case that Cornelisz was almost certainly a psychopath. The ruthless killings were less about survival, Dash argues, and more about Cornelisz’ desire to create his own personal kingdom. Like other psychopaths, Cornelisz believed he could do no wrong, and that God himself inspired his evil deeds.

In 1944, Australian ichthyologist Gilbert Percy Whitley described a new species of sea chub (Kyphosidae) from Houtman Abrolhos, the same chain of islands where the Batavia was lost, and so many people murdered, in 1629. Whitley named the fish Segutilum (now Kyphosus) cornelii, after the “villain” (his word, which he placed in quotes) of the Batavia mutiny.

Personally, I find Whitley’s selection tone-deaf and distasteful. It’s appropriate to link the fish’s type locality with the islands’ infamous place in history. But why honor the man who committed these atrocities? Why not honor the ship, or the men, women and children who suffered and died on that island? Jeronimus Cornelisz represents the worst of humanity. I don’t like it that he’s commemorated in the name of a lovely fish.

2 December

2 December

Astatotilapia flaviijosephi (Lortet 1883)

In the September 2020 issue of Buntbarsche Bulletin, the journal of the American Cichlid Association, Paul Loiselle summarizes the aquarium husbandry of Astatotilapia flaviijosephi, the Jordan Mouthbrooder. As its common name suggests, it’s endemic to the central Jordan River system, including Lake Tiberias (also known as Kinneret), of Israel, Jordan and Syria. In fact, A. flaviijosephi is the only haplochromine cichlid that naturally occurs outside of Africa.

Loiselle includes in his article a brief side essay, “Who Was Flavius Josephus and Why Is a Cichlid Named After Him?” He answered the first of the two questions. Titus Flavius Josephus (37-c. 100), born Yosef ben Matityahu, was a prominent Romano-Jewish scholar, historian and hagiographer, most famous for his book The Wars of the Jews, or History of the Destruction of Jerusalem (also known as The Jewish War).

But Loiselle did not really answer the second question — why Louis Charles Émile Lortet (1836-1909), a physician, botanist, zoologist, paleontologist, Egyptologist and anthropologist, named Chromis (now Astatotilapia) flaviijosephi after a scholar from the first century A.D.

Loiselle wrote: “Educated persons living in the 19th Century were quite familiar with classical literature. Lortet appears to have shared the generally high regard in which the Jewish historian’s writings were held. In his monograph on the fishes of the Levant, he saw fit to express his admiration by naming a distinctive representative of that ichthyofauna in his honor. Lorter’s [sic] use of a patronymic as the species name for this cichlid is echoed in the contemporary Israeli vernacular amnunit yosef (Joseph’s tilapia).”

What Loiselle did not explain is that Lortet was more than just at admirer of Josephus’ historical writings. Lortet actually cited Josephus in his 1883 zoological survey of Lake Tiberias. Josephus had reported a thriving fishing industry on the lake, and mentioned a fish the Romans called “Coracinus.” Lortet identified this fish as Clarias macracanthus, now known as C. gariepinus, one of the air-breathing or “walking” catfishes of the family Clariidae. C. gariepinus widely occurs throughout Africa and the Middle East in just about everywhere there’s fresh water — lakes, rivers, swamps, man-made ponds, even urban sewage systems. “This remarkable catfish,” Lortet wrote, “often grows over 1 meter in length, and when caught and thrown on the sand, it will utter hoarse cries that resemble the meows of an angry cat” (translation). Lortet also saw fit to mention (twice, in fact) that Josephus believed the presence of “Coracinus” in Lake Tiberias was due to an underground connection with the Nile!

Lortet, however, may have been mistaken. Smithsonian ichthyologist Theodore Gill believes that Lortet misidentified Josephus’ “Coracin fish.” The name “Coracinus” dates to Aristotle and has historically been applied to a number of perch-like fishes over the centuries, including drums, damselfishes and, yes, cichlids. Gill believes the fish mentioned in Josephus’ War of the Jews was actually a cichlid — perhaps the very same cichlid that Lortet named A. flaviijosephi 17 centuries later. If so, this means that Lortet honored the Jewish historian not because he had written about a catfish, but the actual fish that now bears his name.

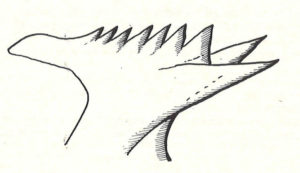

Geotria australis. From: Gray, J. E. 1851. List of the specimens of fish in the collection of the British Museum. Part I. Chondropterygii. London. i-x + 1-160, Pls. 1-2.

25 November

Geotria australis Gray 1851

In 1851, British zoologist John Edward Gray (1800-1875) described and named a peculiar-looking lamprey from Adelaide, South Australia. He called it the Pouched Lamprey because of the “extraordinary development” of a “very large dilatable pouch” hanging from its throat. He called the genus Geotria but did not explain the meaning behind this name, leaving it to us to make an “educated guess” as to his intent. Recently, we came across an explanation of the name that is substantially different from our own. So we took another, closer look. Our conclusion? That we know less about the name than we did before.

Our “educated guess” process usually entails two steps: (1) correctly translating the meaning of the word by tracing its Latin or Greek etymological origin, and (2) applying this meaning to a character or attribute that was mentioned in the original description or, failing that, at least a character or attribute generally known about the taxon at the time. And so, following that process, we drafted and posted the following explanation:

Geotria Gray 1851 — etymology not explained, perhaps from the Greek geotragia, “eating of earth-like substances,” referring to how this lamprey, like other lampreys, uses its suctorial mouth to attach itself to submerged rocks and stones, thus creating the impression that it is feeding on the earth

Our source for the translation of Geotria was the Wiktionary entry for that word, which said it was from the Greek γεωτραγία, or geōtragía, “eating of earth-like substances.” The entry also said, “Like other lampreys pouched lampreys carry stones to a nesting site.” Since Gray did not mention nest-building behavior in his description, we emended the Wiktionary explanation to reflect a lamprey behavior that surely was known to Gray: the use of their suctorial mouths to cling to rocks and even climb small waterfalls and other barriers in freshwater streams. This interpretation fits nicely with the very meaning of the word “lamprey,” derived from lampetra (“rock licker”), and the type genus of the family, Petromyzon, which means “stone sucker.”

A few months ago, while researching the name of an unrelated Australian fish, we came across a paper by bryologist and science writer David Meagher entitled “An etymology of the names of Victorian native freshwater fish,” in the June 2010 issue of Victorian Naturalist. Meagher’s explanation of Geotria surprised us: “presumably from geo– (earth) + Latin atrium (room), alluding to the discovery of the type species G. australis in underground chambers, in which it survives dry periods.”

What? The Pouched Lamprey lives underground? It aestivates like African lungfishes? How did we miss this in Gray’s description?

We quickly returned to Gray’s 1851 text. Gray said nothing about underground chambers (nor did he in a more detailed description of the lamprey in 1853). But we did see a sentence that we had initially overlooked or dismissed as irrelevant: “This development of the pouch, is perhaps to adapt the animal to the long drought of the Australian rivers.”

Meagher apparently connected Gray’s speculation about the pouch to his translation of Geotria: geo– (earth) + Latin atrium (room), thus creating, in our assessment, an erroneous explanation for the name. And, it should be noted, we have found nothing in the literature to substantiate Gray’s suggestion that the lamprey’s pouch helps it survive droughts nor Meagher’s claim that it sequesters in underground chambers (although lamprey ammocoetes live in mud burrows). In fact, G. australis, like other river lampreys, is anadromous. Born in freshwater, it migrates to the ocean where it feeds and matures, and then returns to fresh water to spawn and eventually die.

Although we easily dismissed Meagher’s explanation of the name, we could not dismiss his etymological breakdown of geo + atrium. And so we asked our friend Holger Funk to weigh in on the matter. Dr. Funk is a scholar of Greek and Latin who is researching the emergence of modern ichthyology in the 16th century and currently translating Hippolito Salviani’s Aquatilium Animalium Historiae (1558) into German. He said the Wiktionary translation of geōtragía, “eating of earth-like substances,” was inaccurate. The problem is the phrase “earth-like.” This adjective does not mean “earthy,” as in rocks and minerals, but instead means “products of the earth,” such as grains and vegetables. (Geotria australis, like other parasitic lampreys, is definitely not a vegan!) And even if Gray had based the Pouched Lamprey’s name on geōtragía, Funk asked, why shorten it to the etymogically vague Geotria?

Dr. Funk did find value in Meagher’s geo + atrium etymology, but he suggested that “atrium,” instead of “room,” might mean “house” and by extension “nest,” thus supporting the Wiktionary claim that Geotria refers to the lamprey carrying stones to a nesting site.

All this is well and good except for the fact that nest-building among G. australis has never observed, or at least recorded in the scientific literature. In fact, the first and only in situ observations of the lamprey’s spawning behavior did not occur until 2014-2015, reported by Baker et al. in 2017. According to this paper, G. australis spawns under submerged boulders, with the eggs forming a coagulated cluster adhered to the underside of the boulder. Their observations strongly suggest that while G. australis does indeed use a nest, it does not build a nest from stones and pebbles like their lamprey counterparts in the North Hemisphere.

Baker et al. also provide the first viable explanation for the lamprey’s pouch, termed a gular pouch, which only adult males possess. According to their observations, the male uses his pouch to “groom” the eggs and “vigorously” rub against them while they are hatching, perhaps to ventilate them, increase oxygenation, and remove metabolic wastes.

So what does Geotria mean? We don’t know. The best we can do is summarize the possibilities and address their flaws.

A final question: There are plenty of Greek and Latin words that mean pouch and bag. Why didn’t Gray select one and name the lamprey after its most conspicuous and “extraordinary” (his word) feature? If he had, that would have saved us a lot of etymological trouble.

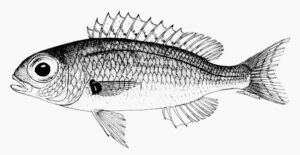

Parascolopsis qantasi. From: Russell, B.C., 1990. FAO Species Catalogue. Vol. 12. Nemipterid fishes of the world. (Threadfin breams, whiptail breams, monocle breams, dwarf monocle breams, and coral breams). Family Nemipteridae. An annotated and illustrated catalogue of nemipterid species known to date. FAO Fish. Synop. 125(12):149p. Rome: FAO.

18 November

Parascolopsis qantasi Russell & Gloerfelt-Tarp 1984

This past Monday, 16 November, was the 100th anniversary of Qantas Airways Limited. And, we’re pretty darned sure, it’s the only airline with a fish named after it.

Qantas was founded in Winton, Queensland, Australia, as Queensland and Northern Territory Aerial Services (hence the acronym Qantas). Its founders believed that the then-fledgling business of air travel might be the way to connect various far-flung outposts in the rural regions of Australia. Its first aircraft was a pre-World War I biplane that could seat a pilot and one passenger. Since then, Qantas has grown to become the largest airline in Australia and, with its kangaroo livery, one of the most recognizable brands in the world.

The fish named after Qantas is Parascolopsis qantasi, a threadfin bream — the Slender Dwarf Monocle Bream (family Nemipteridae) — from the eastern Indian Ocean of Indonesia. According to the etymology section of their description, the authors honored the airline for “invaluable assistance over three years given to the junior author by staff of the Denpasar (Bali) office of the Australian airline Qantas.”

Here’s how the name came about, as told by the junior author, Thomas Gloerfelt-Tarp, to the authors of the upcoming Eponym Dictionary of Fishes:

We were working (1979-1984) on a fisheries bottom trawl survey stretching across Southern Indonesia. This was conducted by the Food & Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations and the German Technical Assistance, plus CSIRO and covered the North West Shelf of Australia. Every day we discovered many undescribed fish. With limited interest from the Indonesian museums, Australia put their hands up to take these fish to complement their own museum collections. We got these fish to Australia by preserving them in formaldehyde, then wrapping them up and putting them in drums and asking Qantas — flying from Bali to various destinations in Australia — if they would freight them on board. Qantas gladly assisted and they did this for free. They would pick them up and fly them to all the museums around the country whose staff gratefully accepted them. 84 new species were found and we thought why not say thank you to Qantas and name a fish after them. It was named with little fanfare. There were some grumblings in the scientific fraternity — “you can’t name a fish after Qantas” — but I said, ‘Well, give it back then!’ But they did not want to relinquish a new species.

While big plans for the airline’s centennial were scaled back due to the pandemic, Qantas did operate a scenic flight over Sydney Harbor to celebrate the big day.

(Our thanks to Bo Boelens and the late Mike Watkins for sharing their Eponym Dictionary of Fishes manuscript.)

11 November

Feroxodon Su, Hardy & Tyler 1986

Learning about this fish’s name made us say “OUCH!”

Feroxodon is a monotypic genus of pufferfishes known from shallow inshore waters along the northern half of Australia. Its name is a combination of ferox, ferocious and odon, tooth, referring to its “fierce” biting habits. As if being too poisonous to eat isn’t enough, this puffer has also been implicated in several unprovoked attacks on human toes.

Two such attacks occurred in 1979 near Proserpine, Queensland, Australia. In one of them, a girl lost three of her toes. In 2012, a five-year-old boy from Queensland required two operations, three stitches, and two weeks in the hospital after a F. multistriatus mauled his feet. The ball of his left big toe was missing and a chunk of flesh was missing from his right heel.

A newspaper account of the incident described the puffer as a “cross between a tadpole and a Great White Shark.”

According to the authors of the name, “Such opportunistic ‘feeding’ behaviour in tetraodontids is indicative of a sometimes highly aggressive predatory nature, which can be likened to a feeding frenzy.”

Like most puffers, F. multistriatus has incredibly strong jaws, which it uses for crushing clams and crustaceans. And the occasional human toe.

4 November

4 November

Lagocephalus sceleratus (Gmelin [ex Forster] 1798)

Pufferfishes are infamous for the toxicity of many species. Their skin and internal organs contain a neurotoxin produced by symbiotic bacteria. When ingested, this neurotoxin can cause a variety of unpleasant and often fatal symptoms. Perhaps the most frightening of these symptom is paralysis, in which victims may be fully lucid in the 4-6 hours before their death. Japanese scientists tested puffer toxins on humans during the notorious Unit 731 program of World War II.

Only one pufferfish (at least among currently valid taxa) has been named for its toxicity. That’s the Silvercheeked Toadfish Lagocephalus sceleratus of the Red Sea, Indo-West Pacific, and a recent invader of the Mediterranean via the Suez Canal (see the warning poster, shown here). The species was formally named by Johann Friedrich Gmelin (1748-1804), who based his brief description on two accounts — a 1777 memoir written by Johann Georg Forster (1754-1794), and an unpublished scientific manuscript written by Georg’s father, Johann Reinhold Forster (1729-1798). Both were naturalists aboard the HMS Resolution (1772-1775) during Captain Cook’s second voyage around the world.

According to the younger Forster, the captain’s clerk purchased a pufferfish from a native at New Caledonia, in the South Pacific, on 4 September 1774. Forster warned Cook that puffers can be poisonous, but Cook said he had eaten puffers before and experienced no ill effects. There wasn’t time to prepare the entire fish, so Cook, and both Forsters nibbled at the liver. By three o’clock in the morning, all three men complained of numbness and shortness of breath. Forster recorded in his notebook that he could not distinguish between the weights of a feather and a quart pot. He felt better in the morning, but by noon was “suddenly seized with sickness” once again. Unable to stand or walk longer than five minutes, he returned to bed and was sick for another two days. All three men survived their ordeal, probably because they ate so little of the fish.

Captain Cook recalled, “When the natives came on board and saw the fish hanging up, they immediately gave us to understand it was not wholesome food, and expressed the utmost abhorrence of it; though no one was observed to do this when the fish was to be sold, or even after it was purchased.”

Someone fed the remains of the puffer to several dogs and a small pig, which all became sick. The dogs survived. The pig died soon afterwards, “being swelled to an unusual size.”

Gmelin named the fish “sceleratus,” noting that it was extremely poisonous when eaten (“comestus veneni vires edens”). Gmelin apparently borrowed the name from the elder Forster’s unpublished manuscript name “sceleratum.” (The manuscript was eventually published, posthumously, in 1844.)

Dictionaries provide multiple translations for “sceleratus.” Accursed. Criminal. Wicked. Villainous. Infamous. Polluted. Heinous. Harmful. Noxious.

All seem to apply.

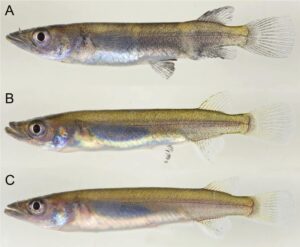

Nomorhamphus aenigma immediately after fixation. (A) holotype, male; (B and C), paratypes, female. From: Kobayashi, H., K. W. A. Masengi and K. Yamahira. 2020. A new “beakless” halfbeak of the genus Nomorhamphus from Sulawesi (Teleostei: Zenarchopteridae). Copeia v. 108 (no. 3): 522-531.

28 October

Nomorhamphus aenigma Kobayashi, Masengi & Yamahira 2020

The specific name of this viviparous halfbeak is a riddle. Literally.

Recently described is the latest issue of Copeia (108, no. 3), N. aenigma occurs in the Cerekang River of Sulawesi Selatan, Indonesia. Unlike other halfbeaks — so named because of the prolonged lower jaw, creating the appearance that the fish has only “half a beak” — N. aenigma is conspicuously “beakless” throughout its entire life. (Some halfbeaks possess the “beak” as juveniles and lose it as they mature.) The name “aenigma,” from the ancient Greek noun for ‘‘riddle,” refers to the riddle raised by this species:

‘‘Why are the mandibles of most halfbeaks long?’’

The authors present an interesting hypothesis. Most halfbeaks swim at water’s surface, where neuromasts on their extended lower jaws may help them locate prey, particularly terrestrial insects that fall into the water. N. aenigma occurs with one such species, N. rex. But unlike N. rex, which swims at the surface, N. aenigma prefers the middle and lower reaches of the stream. The authors posit that N. rex may have evolved short jaws as “ecological character displacement,” the phenomenon wherein two similar or closely-related species that live in the same environment have evolved different traits in order not to compete with each other.

The authors conclude their paper: “To test this hypothesis, detailed comparisons of feeding habits between these two sympatric species [aenigma and rex] are necessary in the future.”

A few words on the meaning of the generic name Nomorhamphus: Proposed by Weber & de Beaufort in 1922, “rhamphus” clearly means beak. The meaning of “nomos” is not so obvious. We suspect it’s from the Greek word for law, custom or tradition. If so, the name may refer to how the lower jaws of this genus do not extend as far as those of other halfbeaks (e.g., Dermogenys) and therefore represent a more “traditional” kind of jaw.

21 October

Fishes from Middle Earth

J. R. R. Tolkien’s Middle Earth legendarium has been a source of fish names since at least 1973. That’s when shark taxonomist Leonard Compagno named the pseudotriakid genus Gollum, remarking how G. attenuatus resembles the “Lord of the Rings” antihero in form and habit.

Other Middle Earth-inspired fish names include:

- The Gollum Galaxias of New Zealand, Galaxias gollumoides McDowall & Chadderton 1999, which, like Gollum, is a “dark little fellow with big round eyes who sometimes frequents a swamp”

- Two driftwood catfish (Auchenipteridae) genera proposed by Steven Grant in 2015: Duringlanis, named after Durin the Deathless, eldest of the Seven Fathers of the Dwarves, referring to the small size of its included species, and Balroglanis, named after the Balrogs, referring to their larger size compared to Duringlanis and the “horns” of their nuchal shield (glanis = general term for catfish)

- A horseface loach, Acantopsis bruinen Boyd, Nam, Phanara & Page 2018, from Cambodia, Thailand and Laos, named for the River Bruinen, or Loudwater, of Rivendell and the flood that took the form of great horses in “The Fellowship of the Ring,” alluding to the common name “horseface loach” for the genus

- A tetra, Astyanax lorien Zanata, Burger & Camelier 2018, whose name is from the Quenya language meaning “Dream Land,” referring to “beautiful” areas on the Chapada Diamantina (Bahia, Brazil) inhabited by this species (Quenya is a fictional language devised by Tolkien, spoken by the Elves)

- The troglophilic Gollum Snakehead of India, Aenigmachanna gollum Britz, Anoop, Dahanukar & Raghavan 2019, which, like Gollum, is a “creature that went underground and during its subterranean life changed its morphological features”

And now, in just the past few months, two more fishes from Middle Earth have been described:

Aspidoras azaghal Tencatt, Muriel-Cunha, Zuanon, Ferreira & Britto 2020 is a callichthyid catfish named for Azaghâl, king of the Broadbeam Dwarves, referring to Terra do Meio (Pará, Brazil, type locality), freely translated as “Middle Earth” in English, and to the fact that this catfish occurs in a mountainous region and reaches a relatively small size, both of which are typical features of Tolkien’s fictional dwarves.*

Pseudophallus galadrielae Dallevo-Gomes, Mattox & Toledo-Piza 2020, a freshwater pipefish from Guatemala, is named for Galadriel (shown here in her cinematic incarnation), the elf ruler of Lothlórien and bearer of the ring Nenya (also known as the ring of water), referring to its additional bony rings (41-55) compared to P. brasiliensis (40-50) and, like all other species of the genus, its occurrence in fresh water.

For an interesting look at the presumed actual fishes of Middle Earth, ichthyologist Philip W. Willink of the Field Museum in Chicago has prepared a handy field guide.

* Although not from Middle Earth, the name of the related Brazilian catfish Aspidoras psammatides Britto, Lima & Santos 2005 derives from Tolkien: it was named after Psamathos Psamathides, the sand sorcerer, from Tolkien’s Roverandom (written in 1925, published in 1998), from psammos, sand, and ides, son of, referring to its sand-dwelling behavior.

The deepwater boxfish now known as Aracana aurita as it appeared in Gray, J. E. 1833 .Illustrations of Indian zoology; chiefly selected from the collection of Major-General Hardwicke, F.R.S. 20 parts [1830-1835] in 2 vols. Pls. 1-202.

Aracana Gray 1833

Aracana is a peculiar name. Peculiar in that Gray spelled it three different ways. Peculiar in that while the name dates to 1833, its spelling dates to 1838. And peculiar in that no one knows what the name means. We present our best guess below.

Aracana is the type genus of Aracanidae, the deepwater boxfishes, comprising six genera with 13 species occurring in the Indo-West Pacific from Hawaii to South Africa, with peak abundance around Australia. They’re related to the boxfishes (Ostraciidae), famous for the square or box-like body shape of many species. But aracanids are considered to be a more primitive form, less boxy in shape, and occurring in deeper waters, usually over 200 m.

British zoologist John Edward Gray (1800-1875) proposed the genus in 1833. “Proposed” may be too generous a word. “Captioned” is more accurate. The name of the genus first appeared as a subgenus of Ostracion (the original boxfish genus) in a series of color plates issued in folio installments from 1830 to 1835 under the collective title “Illustrations of Indian zoology; chiefly selected from the collection of Major-General Hardwicke, F.R.S.” Maj.-Gen. Hardwicke was Thomas Hardwicke (1755-1835), an English soldier and naturalist who collected animals in India under the auspices of East India Company and had them painted in watercolor by Indian artists (all anonymous except for one). He also acquired specimens from other parts of the world and had his Indian artists paint them as well. Gray arranged the paintings for publication and provided names for the species that appeared to be new. There was no descriptive text. Just name and painting.

Here’s where things begin to get peculiar. For the painting of the Australian boxfish Ostracion auritus Shaw 1798, for which Gray proposed a new subgenus, two spellings appear: “Acarana” on the plate itself (shown here), issued in 1833, and “Acerana” on the legend (table of contents) page in the subsequent 1835 folio edition. Note that both spellings differ from “Aracana,” the spelling currently in use. That spelling dates to Gray’s 1838 account of four species he assigned to the subgenus Aracana. Gray did not explain the meaning of the name, nor did he mention the earlier two spellings.

Today, Gray’s 1838 spelling is in use, yet it’s dated to the original 1833 publication of the painting. Or, to put it another way, the name “Aracana” dates to 1833 even though it did not appear in print until 1838!

Today, there are rules in place to prevent such nomenclatural anomalies from occurring. Back then, however, things were more flexible and forgiving. For example, it was okay to propose a name without a written description, and to retain the original authorship of that name when a description was added later. In fact, many zoological nomina, including those of several fishes, date to the names Gray assigned to Hardwicke’s commissions. Whoever first proposed the “Aracana Gray 1833” combination was clearly acknowledging the primacy of Gray’s publication.

But this very same taxonomist — the “first reviser” — also had a choice to make: Which of Gray’s three spellings — Acerana, Acarana or Aracana — should be retained? Two of them are probably misspellings or typos. But which two? By today’s rules, one of the original two spellings would be preferred, ideally “Acarana” because it appeared three years before the “Acerana” spelling in the legend. Ultimately, “Aracana” was selected, probably because it was the spelling Gray used when he formally proposed the subgenus in a descriptive account, and because he mentioned it five times, evidence that it is not a one-time misspelling or typo.

So, what does “Aracana” mean? As far as we know, only one reference has attempted an explanation, the online Monaco Nature Encyclopedia. The author considered Aracana, a city in the landlocked country of Bolivia, and Akarana, the Maori name for Auckland, New Zealand, but wisely dismissed them both.

Although Gray did not explain the etymology of the subgenus (now full genus) Aracana, he provided a clue in his 1838 account. He called these boxfishes “parrot fishes,” perhaps because of their “beautiful” colors and/or their fused teeth, which form beak-like plates, giving them a parrot-like facial appearance. Based on the “parrot fish” name, we suggest that Aracana relates to the Scarlet Macaw, Ara macao, which in Gray’s day also went by the name Aracanga, Macrocercus aracanga.

The similarity between “Aracana” and “Aracanga” is too close to dismiss.

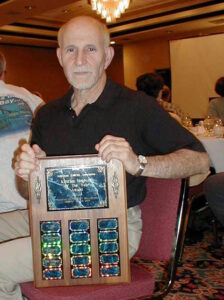

Ken Lazara with this 2002 Killifish Hobbyist of the Year award from the American Killifsh Association.

7 October

In memoriam: Kenneth J. Lazara

Yesterday I learned that Ken Lazara passed away on 27 August at the age of 81. Ken was the “junior” author of The ETYFish Project.

I began work on The ETYFish Project in 2009. For the first five years I collaborated with Ken, who provided much of the mundane but necessary library work during his tenure as a Research Associate at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Every week or so I sent Ken a list of original descriptions I did not own or could not find online. He would then visit the Museum’s library, scan the papers, and email them to me. He also helped translate some of the non-English texts, or found colleagues at the Museum to translate them for me. He served in this capacity for five years. I added his name as co-author when The ETYFish Project went online in 2013.

Ken and I first met each other online when I was researching and writing the five-part “Annotated Checklist of North American Freshwater Fishes” for the North American Native Fishes Association (2005-2009). He particularly enjoyed the etymology sections I included, and helped me track down the meanings of some of the more enigmatic names. When I told him about my idea of researching the etymologies of all fish species, he immediately volunteered his library and research services.

I met Ken in person only once. It was during the early years of the Project, and even then I could see that he was frail. Amazingly, despite his declining health, he somehow managed to visit the Museum in Manhattan from his Brooklyn home and continue to scan papers for me. Eventually his visits became less frequent until they ceased altogether. He never told me why but I knew.

Ken remained a steady correspondent over email. I sought his counsel on difficult names and some of the more speculative explanations I was proposing. But then he stopped replying. I called him and left messages. He never returned the calls. I suspected his health had taken a serious turn for the worse. Through a contact at the American Killifish Association I learned that it had.

Before he retired, Ken was a physics professor at the United States Merchant Marine Academy in Kings Point, New York. During his spare time, and during the early years of his retirement, he was a celebrated and influential killifish hobbyist with a keen interest in taxonomic minutiae. He contributed several important articles on killifish taxonomy to the journal Copeia and described three new killifish species — Maratecoara lacortei, Spectrolebias costai and Plesiolebias aruana — in 1991. He collaborated on the description of Aphaniops stiassnyae in 2001, the same year he released his magnum opus, The Killifishes: An Annotated Checklist, Synonymy, and Bibliography of Recent Oviparous Cyprinodontiform Fishes, also known as The Killifish Master Index (4th edition).

I miss Ken’s superb bibliographical detective work, his sharp editorial eye, and his passion for nomenclatural arcana.

I wish we had begun our collaboration 10 years earlier.

Short-nosed form of the Shortnose Batfish, Ogcocephalus nasutus. Photo by Gilles San Martin. Courtesy: Wikipedia.

30 September

Ogcocephalus nasutus (Cuvier 1829)

Here’s an amusing case of a fish’s common name meaning the exact opposite of its scientific name.

Ogcocephalus nasutus is a batfish that occurs in the Western Atlantic from southern Florida to eastern Venezuela. It’s named nasutus, meaning long-nosed, large-nosed or big-nosed, referring to the well-developed horn protruding from its rostrum.

Yet the English common name for this fish is Shortnose Batfish!

Here’s our explanation for the discrepancy.

All Ogcocephalus have long rostra. Ogcocephalus nasutus was the second named species in the genus (there are now 12 validly recognized species). So its large rostral process was indeed a clearly visible physical attribute worthy to be referenced in its name. But as more species began to be described in the genus, its big nose simply wasn’t as big as some of its congeners. And as more specimens of O. nasutus were collected, cataloged and measured, taxonomists discovered that its rostral length is quite variable. Sometimes it’s long, looking almost finger-like, and sometimes it’s short, ranging from a knob to a thick cone in appearance.

We’re not sure when “Shortnose Batfish” first appeared in the literature, but whoever coined it was probably comparing the length of this batfish’s rostral process to that of its congeners, particularly the Longnose Batfish, Ogcocephalus corniger. This species, described by batfish expert Margaret Bradbury in 1980, also occurs in the Western Atlantic but north and west of O. nasutus, from North Carolina to Florida, and along the northeastern Gulf of Mexico to Louisiana. Bradbury named it “corniger,” meaning horn-bearer, for its long, upturned rostrum. In fact, Bradbury noted that its long rostrum separates it from all other species of Ogcocephalus except O. vespertilio, O. pumilus, and “long-nosed morphs” of O. nasutus.

In other words, the “long-nosed” Ogcocephalus is called the Shortnose Batfish because its nose, although long, is usually not as long as others in its genus.

Like other members of the anglerfish order Lophiiformes, batfishes possess an angling apparatus — the illicium (rod) and esca (bait) — by which they attract prey. On Ogcocephalus species, this apparatus is attached to a cavity just beneath the rostrum. We’re sure Ogcocephalus nasutus would agree it’s not the rostrum’s size, but rather its performance, that matters.

(A) Membras pygmaea, (B) Membras procera. From: Chernoff et al. 2020. Two new miniature silverside fishes of the genus Membras Bonaparte (Atheriniformes, Atherinopsidae) from the Tropical North Atlantic Ocean. Zootaxa 4852 (2): 191–202.

23 September

Two silversides, 12 authors

How many people does it take to describe a new species of fish?

12, apparently:

Membras procera Chernoff, Machado-Allison, Escobedo, Freiburger, Henderson, Hennessy, Kohn, Neri, Parikh, Scobell, Silverstone & Young 2020

Membras pygmaea Chernoff, Machado-Allison, Escobedo, Freiburger, Henderson, Hennessy, Kohn, Neri, Parikh, Scobell, Silverstone & Young 2020

These two species of miniature silversides (Atherinopsidae) were recently described from coastal habitats in the tropical North Atlantic. Membras procera, from the Gulf of Urabá, Colombia, is named for its overall shape (procera = long or slender), reaching just 36.3 mm SL. Membras pygmaea, from Brus Lagoon, Honduras, is named for its diminutive size, <41 mm SL.

We believe 12 is the record for the highest number of authors of a fish name, breaking the record previously set by the neotropical cichlid Apistogramma allpahuayo, proposed by 11 authors — Römer, Beninde, Duponchelle, Díaz, Ortega, Hahn, Soares, Díaz Cachay, García Dávila, Cornejo & Renno — in 2012.

Pseudaphritis urvillii. Photo by Peter J. Unmack.

16 September

Pseudaphritis urvillii (Valenciennes 1832)

The Congolli, Pseudaphritis urvillii (Valenciennes 1832), is the sole member of the family Pseudaphritidae. It’s a catadromous fish from coastal rivers of southern Australia and Tasmania, living in fresh water as adults and moving downstream to estuaries to spawn. There’s a lot packed into its generic and specific names.

The genus Pseudaphritis was proposed by François Louis Nompar de Caumont La Force, comte de (count of) Castelnau (1810-1880), a French naturalist who published several papers on Australian fishes in the 1870s, including this one in 1872. The first part of the name is formed with the prefix pseudo-, meaning “false,” often used by taxonomists to connote how one taxon may resemble another and may falsely be mistaken for it. In this case, Pseudaphritis is named for its resemblance to Aphritis, “but the scales are rather large, the first dorsal has seven rays, and just in front of the anal there is a short fin composed of two spines.”

The name Aphritis, at least in fishes, is no longer in use. The great French naturalist Achilles Valenciennes proposed it for what is now Pseudaphritis urvillii in 1832, but did not realize that it had already been in use for a genus of flies, Aphritis, proposed by French zoologist Pierre André Latreille in 1805. (Latreille was equally silent on why he selected that name.) The name was replaced by the Baltic zoologist Friedrich Wilhelm Karl (“Carlos”) Berg (1843-1902), who renamed it Phricus in 1895. Eventually, ichthyologists determined that Phricus and Pseudaphritis were the same genus, in which case the name would default to the earliest available name. Since Aphritis was unavailable, that honor fell to Pseudaphritis. And so, opposite of what the name means, the “false Aphritis” is actually an Aphritis!

Valenciennes did not explain why he selected the name Aphritis nor what the word means. The name dates to Aristotle, who described it as a kind of anchovy or whitebait. The Greco-Egyptian author Athenaeus (late 2nd to early 3rd centuries AD) said it was not produced from roe, as Aristotle had written, but from a foam that floats upon the surface of the water and collects in quantities after heavy rains. Indeed, aphritis is derived from aphros, meaning “foam.” There is, of course, nothing anchovy-like about P. urvillii, but Aristotle used the term as a catch-all for any small fish that’s edible when boiled. It’s possible that Valenciennes, as did his predecessor and mentor Georges Cuvier, simply repurposed a fish name used by the ancients with no apparent taxonomic relevance.

Fortunately, the specific name is not a mystery. Valenciennes named it in honor of Jules Sébastien César Dumont d’Urville (1790-1842), who led the expedition during which the type was collected. Dumont d’Urville was a French naval officer who spoke Latin, Greek, English, German, Italian, Russian, Chinese, and Hebrew in addition to his native French. Apparently his knack for languages helped him pick up some of the lesser-known and more exotics languages of the South Pacific. In addition to picking up languages, Dumont d’Urville also acquired a large collection of plant and animal specimens that kept Cuvier, Valenciennes and others quite busy. A number of plants are named after him, as is the Australian longtom or needlefish Strongylura urvillii. The Adélie Penguin Pygoscelis adeliae was named after his wife Adélie.

1842 illustration of the Versailles train derailment and fire that killed Jules Sébastien César Dumont d’Urville, his wife and son, and over 50 others.

For all his years at sea, it was travel on land that claimed Dumont d’Urville’s life. On 8 May 1842, he and his wife and only son boarded a train from Versailles to Paris. Moving at a high rate of speed, the first of its two locomotives snapped an axle and came to a dead stop. The second locomotive was then driven by its momentum on top of the first, scattering the contents of both fire boxes among the debris. Three carriages crowded with passengers were then piled on top of this burning mass and crushed into each other. The carriages were newly painted and blazed up like kindling. Dumont and his family — along with 50 or so other people — perished in the flames.

9 September

9 September

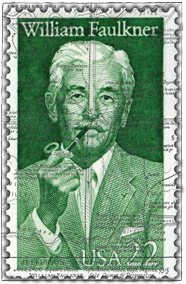

Etheostoma faulkneri, the Yoknapatawpha Darter

Here’s a rare case of a fish’s common name being longer and harder to pronounce than its specific epithet.

Etheostoma faulkneri was recently described (31 August) as a new species of darter (Percidae) from the Little Tallahatchie and Yocona river watersheds of north-central Mississippi (USA). The authors — Ken A. Sterling and Melvin L. Warren, Jr. — named it for the Nobel Prize-winning American writer William Faulkner (1897-1962). Faulkner’s 1929 novel The Sound and the Fury ranks #6 on the Modern Library’s list of the 100 best English-language novels.

Etheostoma faulkneri, male holotype. From: Sterling KA, Warren, Jr. ML. 2020. Description of a new species of cryptic snubnose darter (Percidae: Etheostomatinae) endemic to north-central Mississippi. PeerJ 8:e9807

Faulkner was a native of the Oxford, Mississippi, the area where the darter occurs. “The landscape was an important theme in many of his works,” Sterling and Warren wrote, “and the actions of his characters were often influenced by the lands and streams surrounding his fictional Jefferson, Mississippi, including the Yocona River, which he renamed the Yoknapatawpha.”

“Yoknapatawpha” is the original name of the Yocona River. It is derived from two words from the language of the area’s indigenous Chickasaw people: Yocona and petopha, meaning “split land.” Faulkner himself said the name means “water flows slow through flat land.” Many of his novels took place in this imaginary county, as did his 1930 short story “A Rose for Emily,” a staple of many American high-school literature classes.

While we’re all for fishes being named after famous writers and incorporating local or indigenous names, we can’t imagine too many people outside Yocona County, Mississippi, commonly calling this fish the “Yoknapatawpha Darter.”

Speaking of darters named after famous Americans, here’s a pun that at least country-music fans should get right away. What if a darter species was named after singer-songwriter Loretta Lynn? Its common name would be “Coal Miner’s Darter.”

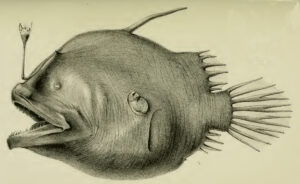

Oneirodes eschrichtii. From: Lütken, D. F. 1871. Oneirodes eschrichtii Ltk. en ny gronlandsk Tudsefisk. Oversigt over det Kongl. Danske Vidensk. Selsk. Forhandl Kjobenhavn 1871 (2): 56-74+ 9-17, Pl. 2.

2 September

Oneirodes Lütken 1871

Deep-sea anglerfishes (ceratioids) are arguably the most bizarre and malevolent-looking fishes in the world. That’s why many have the demonic common name “seadevil.” But one family of deep-sea anglers has a peaceful, illusory, even ethereal-sounding name. Dreamers. And like most things in a dream, the name makes sense — and doesn’t make sense —at the same time.

In 1845, Carl Peter Holbøll (1795-1856), an officer in the Danish Royal Navy and amateur naturalist, obtained a fish from the deep waters off Greenland. He sent it to physiology and anatomy professor Daniel Frederick Eschricht (1798-1863) at the University of Copenhagen, where it sat on a shelf, unnoticed, for 25 years. Danish professor Christian Frederick Lütken (1827-1901) found the specimen and realized it was different from the three other genera of deep-sea anglers known at the time. Lütken wrote a lengthy and detailed description of the specimen, which appeared in three languages, Danish, French and English. He named the fish Oneirodes eschrichtii, after the man who shelved it and forgot about it. In a footnote Lütken said the generic name means “dream-like” (óneiros, dream, and eîdos, form or likeness). He did not explain why he selected that name. We combed through all three versions of the description looking for clues, finding none.

Over the decades, ichthyologists have attempted to interpret the name, confidently, not letting on that they’re just guessing. In 1898, Jordan & Evermann, in Fishes of North and Middle America (volume 3), say the name refers to its small eyes almost covered by skin, presumably alluding to how the fish swims with its eyes closed, as if asleep, perhaps dreaming of its next meal what with food being scarce in the vast and desolate abyss.

In 1968, in their fine little book Deep-water Fishes of California, Fitch & Lavenberg say the name means “something out of a dream, in reference to its almost unbelievable shape.”

A third explanation comes from Theodore W. Pietsch, the world authority on deep-sea anglers. In his 2009 magnum opus Oceanic Anglerfishes: Extraordinary Diversity in the Deep Sea, Dr. Pietsch said Oneirodes is “perhaps the most appropriate of the many early names assigned to deep-sea anglerfishes,” implying that O. eschrichtii is “so strange and marvelous that it could only be imagined in the dark of the night during a state of unconsciousness.”

At some point, Oneirodes was given the common name “dreamer,” evoking “dream-like” and “out of a dream” (as humans perceive the fish), but oddly turning the adjective into a noun, i.e., one who dreams. We’re not sure when this happened. The earliest mention we’ve found is the Fitch & Lavenberg book from 1968.

Maybe we’re interpreting Lütken’s “dream-like” the wrong way. Take a look at the illustration that accompanied his description (shown here). That’s one bizarre and scary looking fish! By calling it “dream-like,” was Lütken actually saying it was “nightmarish”? In other words, the fish is not so much fantastical, surreal or weird the way dreams are weird. It’s creepy and monstrous and indeed a devil from the deep.

Theodore Pietsch’s student James Wilder Orr raised this possibility when he named a related species, Oneirodes epithales, in 1991. “Epithales” is Greek for nightmare. Like Christian Frederick Lütken, Dr. Orr did not explain why he selected this name. So we asked him via email. “I always thought it was funny that species of Oneirodes, all of which are black blobs, would be called Dreamers,” he replied. “The picture of a fish drifting along dreamily, lighting the deep-sea world with a little light [bioluminescent esca, the anglerfish’s “bait”] was a nice fancy. But the fact that the little light was attracting innocent prey that were to be engulfed by a massive mouth full of sharp teeth seemed nightmarish. Hence, the name.”

Perhaps Lütken felt the same way about O. eschrichtii in 1871. It’s the stuff of dreams all right. Bad dreams.

Dreams with sharp teeth.

Devario memorialis. From: Sudasinghe, H., R. Pethiyagoda and M. Meegaskumbura. 2020. Evolution of Sri Lanka’s giant danios (Teleostei: Cyprinidae: Devario): teasing apart species in a recent diversification. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution v. 149. Article 106853.

26 August

Devario memorialis Sudasinghea, Pethiyagoda & Meegaskumbura 2020

On 14 May 2016, a massive low-pressure system formed over the Bay of Bengal, causing torrential rainfall across Sri Lanka. It strengthened to form Cyclone Roanu. Over the next four days, the rain caused devastating floods and landslides across the eastern and southern parts of the country. According to Wikipedia, 101 people died and 100 are still missing.

On 17 May, a landslide occurred in Samsarakanda near Aranayaka in Kegalle District. It buried several homes, killing 21 people and leaving 123 missing. On this day, a team of biologists were conducting fieldwork near Aranayaka. They collected several fish species in a 3-km stretch of a headwater stream of the Ma Oya (river), at an elevation range of 238–266 m above sea level. The most abundant fish in the area, usually observed in shoals, was a small, colorful cyprinoid related to the popular danios of aquarium fame. It turned out to be a new species, now given the name Devario memorialis. The authors wrote:

“The species is named in memory of those who perished in the disastrous landslide at Aranayake, the type locality, in May 2016, while our fieldwork was in progress.”

The generic name Devario dates to German zoologist Jacob Heckel (1790-1857). He proposed the genus in 1843, establishing (and naming) it for Cyprinus devario Hamilton 1822 of India, Bangladesh, Myanmar and Nepal. “Devario” is a latinization of “Debari,” the local Bengali name for this species.

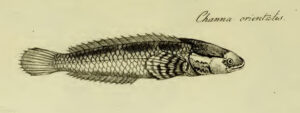

Channa orientalis. From: Bloch, M. E. and J. G. Schneider. 1801. M. E. Blochii, Systema Ichthyologiae Iconibus cx Ilustratum. Post obitum auctoris opus inchoatum absolvit, correxit, interpolavit Jo. Gottlob Schneider, Saxo. Berolini. Sumtibus Auctoris Impressum et Bibliopolio Sanderiano Commissum. i-lx + 1-584, Pls. 1-110.

19 August

Channa Scopoli (ex Gronow) 1777

The snakehead genus Channa represents a group of air-breathing, predatory Asian fishes well-known in aquaria, fish culture, angling, and native medicines, and for the invasive tendencies of some species stocked outside of their native ranges. The meaning of their generic name is not so well-known. In fact, we’re not sure what it means.

The name entered the literature in 1763, in Zoophylacii Gronoviani by Dutch naturalist Laurens Theodorus Gronovius (also known as Gronow, 1730-1777). Gronovius had amassed a large private collection of plant and animals specimens, including a snakehead he had acquired from somewhere in “India Orientali,” i.e., Asia. He called the genus Channa but did not explain why. Since Gronovius did not adopt Linnaeus’ still-young system of binomial nomenclature, his introduction of the name Channa is not considered available for nomenclatural purposes. Italian-Austrian physician-naturalist Giovanni Antonio Scopoli (1723-1788) made the name available in 1777 when he published Gronow’s name in proper Linnaean form. Again, no explanation of what the name means.

Over the decades, scholars have guessed that Channa is derived from either channe or channos, a Greek name for a wide-mouthed fish of the sea. As predators, Channa have large mouths, so the name seems to fit. In addition, Greeks and Romans had called some Mediterranean wrasses Channa, Channus and Canna. So maybe Gronovius borrowed the name, or thought there was something wrasse-like about the snakehead. We’ll likely never know.

A week or so ago, Richard van der Laan, one of the editors of Eschmeyer’s Catalog of Fishes, alerted us to a new paper on the genetic diversity of the Ceylon Snakehead Channa orientalis, now considered the species Gronovius had in his collection. The authors proposed an interesting new explanation for the name.

First, the authors were able to narrow Gronovius’ “India Orientali” down to a more specific type locality — southwestern Sri Lanka. There, they say, the local (Sinhala) name for small snakeheads is kanaya. Since that area was under Dutch rule at the time (which may explain how Gronovius acquired his specimen), the authors posit that Channa — pronounced “kanna” — is a Dutch transliteration of kanaya.

Very interesting indeed. But there are two problems with this explanation. First, the authors do not even consider the possibility that Channa could be derived from the Greek channe or channos. “Unlike most of Gronovius’s generic names,” they wrote, “Channa does not appear to be rooted in Greek or Latin.” Except it does appear to be rooted in Greek!

Problem #2 is more vexing. According to Richard van der Laan, a Dutchman himself, the Dutch pronunciation of Channa is not “kanna.” It’s actually “ganna.”

We’re not saying there is no etymological connection between Channa and kanaya. But we are saying the evidence is weak.

A 1900s greeting card reading “Greetings from Krampus!”

12 August

Protomelas krampus Dierickx & Snoeks 2020

Paedophagia among cichlid fishes of Lake Victoria and Lake Malawi has inspired some interesting names.

The genus Caprichromis Eccles & Trewavas 1989 is based on capra, Latin for goat, for the butting or ramming behavior these fishes use to force mouthbrooding females of other cichlid species to relinquish their broods.

The trivial name of Haplochromis gracilifur Vranken, van Steenberge & Snoeks 2019 means “slender thief,” referring to its slender body and how it steals fry from the mouths of mouthbrooding cichlids.

And Haplochromis cronus Greenwood 1959 is possibly named for Cronus, from Greek mythology, who devoured his sons as soon as they were born. (See the 20 June 2018 “Name of the Week” for the complete story.)

Now there’s Protomelas krampus, a recently described paedophagous cichlid from Lake Malawi. It’s named for Krampus, a demon character in European folklore who puts naughty children in a bag and takes them away, reminiscent of this cichlid’s paedophagous behavior.

The name also connects the goat-like appearance of Krampus with the cichlid’s goat-like butting behavior (similar to that of the genus Caprichromis, mentioned above).

Unlike other paedophages whose behavior has been recorded, P. krampus attacks mouthbrooding females from above. According to Ad Konings, in the second edition of his Malaŵi Cichlids in their Natural Habitat (2016), “Such attacks are sometimes initiated several meters above the victim. … In most observed instances the females were aware of the approaching thief and chased it away. The diagonal position of the mouth may be an adaptation to this hunting technique since, coming from above, it will be in a straight line with the fry when these are expelled.”

A juvenile Plectorinchus pica, showing its magpie-like coloration. Source: Andrew J. Green / Reef Life Survey.

5 August

Plectorhinchus pica (Cuvier 1828)

It’s a grammatical rule that some taxonomists overlook or apply incorrectly. If a species-group name is an adjective, then it must agree in gender (masculine, feminine, neuter) with the generic name with which it is combined. If a species-group name is a noun, then it does not need to agree in gender with the generic name. This rule (Article 31.2 of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature) accounts for many minor changes in the spelling of names when a species is reclassified from one genus to a different genus with a different gender. Hypothetically, a fish named for its silvery coloration could be known under three different spellings if it has been placed in different genera over the years, e.g., argenteus (masculine), argentea (feminine) or argenteum (neuter).

As stated above, some taxonomists, perhaps not properly schooled in Latin grammar, overlook this rule. But at other times, taxonomists enforce the rule but do so incorrectly when they confuse an adjective for a noun or vice-versa. (This can be tricky: Does “spilurus” mean spot tail or spot-tailed? The rule of thumb is that the name is always a noun unless the author has indicated otherwise.)

While working on the grunt family Haemulidae, we discovered that a species-level name, long treated as an adjective, is actually a noun. Plectorhinchus pica, the Painted Sweetlips, occurs in coral reefs of the Indian and western Pacific oceans at depths of 3 to 50 m. It occasionally shows up in the aquarium trade. Georges Cuvier named it Diagramma pica, first in a plate (published in 1828), then in a written description two years later. Cuvier did not explain the meaning of the name, but he gave it a French vernacular: “Le Diagramme Pie.”

“Pie” is French for magpie. “Pica” is the Latin equivalent of the word. Indeed, the scientific name of the European Magpie is Pica pica. So “pica” is clearly a noun. Our guess is that the name refers to the black-and-white (i.e., magpie-like) color of juveniles. The rare book in which the plate was published has not been digitized (nor do we own it) so we cannot reproduce it here.

At some point (we don’t know when), Diagramma pica was moved to its current genus, Plectorhinchus. Whoever made the move (we don’t know who), or a subsequent taxonomist, apparently treated “pica” as an adjective and emended the spelling to “picus.” And there the spelling remained for many years until we had a look.

Eschmeyer’s Catalog of Fishes has added a note that the name is a noun and, per our recommendation, has emended the spelling back to Cuvier’s original “pica.” Whether future taxonomists take note and “picus” falls out of use remains to be seen.

Seminemacheilus dursunavsari, holotype, NUIC-1811, male. From: Çiçek, E. 2020. Seminemacheilus dursunavsari, a new nemacheilid species (Teleostei: Nemacheilidae) from Turkey. Iranian Journal of Ichthyology v. 7 (no. 1): 68-77.

29 July

Seminemacheilus dursunavsari vs. Seminemacheilus tubae

It’s rare for one taxonomist to accuse others of “unethical” behavior in the pages of a scientific journal. But that’s what happened here.

In March 2020, Turkish ichthyologist Erdoğan Çiçek described Seminemacheilus dursunavsari, a new species of nemacheilid loach from Konya province, Turkey, in the Iranian Journal of Ichthyology. He named it in honor of marine biologist Dursun Avşar (Cukurova University, Adana, Turkey), for his support as Çiçek’s supervisor.

Three months later, a team of four taxonomists — Baran Yoğurtçuoğlu, Cüneyt Kaya, Matthias F. Geiger and Jörg Freyhof — declared that S. dursunavsari was improperly described and gave it a new name. Publishing in the journal Zootaxa, Yoğurtçuoğlu et al. said that Çiçek neglected to mention the name of the museum where the name-bearing types of the new species are deposited, as required by Article 16.4.2 of the International Code for Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN).

Let’s repeat the important phrase here, in caps for emphasis: NEGLECTED TO MENTION THE NAME OF THE MUSEUM WHERE THE NAME-BEARING TYPES OF THE NEW SPECIES ARE DEPOSITED.

Although Çiçek designated “NUIC-1811” as the holotype, he did not name the “NUIC” collection beyond its acronym nor describe where the collection is located. For this reason, Yoğurtçuoğlu et al. claim that Seminemacheilus dursunavsari Çiçek 2020 is an invalid name that fails to meet the requirements of the ICZN. So they renamed it Seminemacheilus tubae, in honor of the second author’s’ wife, Tuğba (Tuba) Kaya, for her “endless patience and support with him and his work.”

Çiçek was unhappy about this. He quickly submitted and published a short response and erratum, also published in the Iranian Journal of Ichthyology. He said that none of the authors of the second paper notified him of the error. Instead, they “followed an unethical approach” by renaming the fish without giving Çiçek the opportunity to correct the editorial error.

Çiçek also pointed out that “NUIC” is a known international museum code for the Ichthyology Collections of Nevsehir Haci Bektas Veli University in Nevşehir, Turkey — a fact clearly evident in the author’s mailing address on the title page, and a fact that must be known by the two senior authors of the replacement name, who are also Turkish.

For now, we’re following Eschmeyer’s Catalog of Fishes in recognizing S. dursunavsari over S. tubae. According to ECoF (6 July 2020 edition): “Original description failed to mention explicitly the location where the types are deposited [ICZN Art. 16.4.2], but it was recognizable by indication, and address provided on title page. … We temporarily treat this taxon as valid, but a decision by ICZN may be required.”

Without knowing anything beyond the above-stated facts, we offer the following observations and questions:

1) We’re sticklers for nomenclatural accuracy and proper procedure, but throwing out a name because the author forgot to properly credit a museum seems unnecessarily strict and petty.

2) Contacting Çiçek about the error and giving him the chance to fix it would have been the courteous, professional thing to do — and it would have prevented adding another name to the literature for future taxonomists to deal with.

3) Renaming the fish in honor of a different person seems cold-hearted to us. They easily could have added the museum abbreviation and retained the dursunavsari name even while claiming authorship for themselves.

4) We’re surprised that Rohan Pethiyagoda, who accepted the Yoğurtçuoğlu et al. manuscript for Zootaxa, and other editors and reviewers for that journal, allowed the description of S. tubae to get published. Would other journals have accepted the name?

5) Was there any previous animosity between Çiçek and Yoğurtçuoğlu et al.? We can’t help wonder.

6) We feel sorry for the two individuals for whom the competing nomens honor, Dursun Avşar and Tuğba (Tuba) Kaya. They’re innocent bystanders in this contest for nomenclatural priority, yet it is their names and identities which are at stake. Having a fish named after you must be nice. Having that honor taken away by a technicality will no doubt sting. Knowing that you were given the honor because of said technicality probably doesn’t feel good either.

Naso tergus, (a) adult male holotype, (b) adult female paratype. From: Ho, H.-C., K.-N. Shen and C.-W. Chang. 2011. A new species of the unicornfish genus Naso (Teleostei: Acanthuridae) from Taiwan, with comments on its phylogenetic relationship. Raffles Bulletin of Zoology v. 59 (no. 2): 205-211.

22 July

Naso tergus Ho, Shen & Chang 2011

It must be a challenge for some Chinese ichthyologists to coin and correctly form biological nomens when the Latin alphabet is so different from their form of writing. Without at least a working knowledge of Latin and its Romance-language descendants, words derived from Latin and Greek and the syntactical complexities of Latin grammar must seem confoundingly strange. Maybe that’s why so many Chinese fish taxonomists keep it simple and coin locative names with the suffix –ensis: guangxiensis, lancangjiangensis, qiongzhongensis, szechuanensis, and around 380 others.

Here’s a name in which the authors, possibly with an English-Latin dictionary in hand, tried to come up with a descriptive non-locative name. Unfortunately, they picked the wrong Latin word.

Naso tergus is a unicornfish (Acanthuridae) discovered off the coast of Taiwan in 2010. According to the etymology section, “The species name, tergus, meaning ‘to hide’, refers to the typical appearance of this species that makes it resemble subadults of many other Naso species.” In other words, N. tergus so closely resembles some of its congeners that it “hid in plain sight” — at least until some molecularists took a closer look at its ETS2, 16S and Cyt b genetic markers.

It seems the authors did not realize that the Anglo-Saxon “hide” is a homograph — a word that shares the same spelling as another word, and often the same pronunciation, but can have two different meanings. In this case, “hide” can be a verb (to conceal) and a noun (back, skin, leather). However, the Latin equivalents of these meanings of “hide” are different words. The authors selected, “tergus,” which refers specifically to the noun. A better name would have been “tectus,” which means concealed, secret or disguised.

For what it’s worth, both definitions of the Anglo-Saxon “hide” appear to have a common ancestor. Hide, the verb, is from the Old English hydan. The noun (large animal skin) is from another Old English word, hyd. The words are related in that they both connote a “covering.”

Fundulus nottii © Uland Thomas. Courtesy: North American Native Fishes Association.

15 July

Fundulus nottii (Agassiz 1854)

Two weeks ago, the American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists announced that it was changing the name of its prestigious journal, Copeia, because the scientist for whom it was named, ichthyologist-herpetologist Edward Drinker Cope (1840-1897), held and promoted repugnant racist views.

It was not uncommon for American biologists of the 19th and early 20th centuries to promote white superiority and eugenics under the banner of science. We’ve touched upon the subject in two previous “Name of the Weeks” (26 July 2017, Ctenogobius shufeldti and 3 June 2020, Agonomalus jordani). Here’s another example:

The Bayou Topminnow Fundulus nottii (Agassiz 1854) is a fundulid killifish that occurs in lakes, ponds and slow-moving backwater and overflow pools of rivers in the southeastern United States (Mississippi, Louisiana and Alabama). It was named in honor of Josiah Clark Nott (1804-1873), a medical doctor from Mobile, Alabama, who sent the holotype to Harvard biologist-geologist Louis Agassiz (1807-1873). But fishes were not the only interest Agassiz and Nott had in common. They also shared the belief that African blacks were biologically inferior to European whites.

Agassiz was a proponent of “polygenesis,” a theory of human origins that posits the view that the human races are of different origins. Agassiz gave it a Creationist spin: He believed only white people descended from Adam and Eve and that blacks and whites could be regarded as different species. What’s more, Agassiz admits being repulsed by black people. “In seeing their black faces with their thick lips and grimacing teeth,” he wrote, “their large curved nails, and especially the livid color of their palms, I could not take my eyes off their face in order to tell them to stay far away.”

While Agassiz never supported slavery, Josiah Clark Nott certainly did. Like many white people of the antebellum American south, he owned slaves. Nott once claimed, “the negro achieves his greatest perfection, physical and moral, and also greatest longevity, in a state of slavery.”

While we can remove statues, take down Confederate flags, and change the names of journals, Fundulus nottii will forever honor Josiah Clark Nott. Naming a plant or animal after someone who harbors racist or other offensive views is deemed acceptable as long as the description does not explicitly honor the person for such views.

If we changed F. nottii, then we would need to do the same for the dozens, if not hundreds, of fish names that honor Jordan, Cope, and others with repugnant beliefs by today’s standards. Doing so would create nomenclatural havoc.

8 July

8 July

Siganus doliatus Guérin-Méneville 1829-34

This rabbitfish from the Indo-West Pacific represents an oddity in ichthyological nomenclature. As far as we know, it’s the only fish taxon whose publication date is unknown.

The name dates to a plate (shown here), back in the pre-ICZN days when an illustration of a plant or animal, as long as it was captioned with a proper binomial, was sufficient to establish a name in the literature. Trouble is, no one knows precisely when this plate was published.