NAMES OF THE WEEK from: 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2019 2020 2021 2022 2023 2024 2025

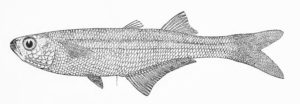

Atherinella nepenthe. From: Myers, G. S. and C. B. Wade. 1942. The Pacific American atherinid fishes of the genera Eurystole, Nectarges, Coleotropis and Melanorhinus. Allan Hancock Pacific Expedition 1932-40, Los Angeles v. 9 (no. 5): 113-149, Pls. 17-19.

26 December

Atherinella nepenthe (Myers & Wade 1942)

The name of this silverside (Atherinopsidae) from the Eastern Pacific of México and Central America is noteworthy for two reasons. The authors leave it up to the reader to decide what it means. And the name reflects the authors’ state of mind during a turbulent, uncertain time in world history.

Nepenthe is a fictional medicine for sorrow mentioned in Greek mythology. Figuratively, nepenthe is anything that makes sorrow go away. “To its users,” Myers and Wade wrote, “is left the interpretation of the name; let them consider the habits and bright appearance of the fish, the systematic tangle which its discovery cleared up, and the murky future of freedom and science in the world at large at the time the authors immersed themselves in its description.”

The “systematic tangle” refers to how the species was initially confused with the closely related Eurystole eriarcha. In fact, when David Starr Jordan proposed the genus Eurystole in 1895, he based his description on a specimen of A. nepenthe instead of A. eriarcha. This created a problem: Should the first species of a genus proposed in 1895 be a species that wasn’t described until 46 years later? “This appeals to us as preposterous,” Myers and Wade wrote. They found a loophole in the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature that allowed them to retain eriarcha in Eurystole while they created a new genus for nepenthe (Nectarges). Alas, both genera have not stood up to further scrutiny and are both considered junior synonyms of Atherinella today.

While fretting over this taxonomic minutiae, Myers and Wade were clearly mindful of greater, more troubling issues facing the world. The time was World War II, just three months after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, when the “future of freedom and science” indeed seemed “murky.” They found in describing this bright silvery fish — which they collected at night by fishing with dip-nets under lights rigged over the sides of ships at anchor — a nepenthe from the mounting worries of a world at war.

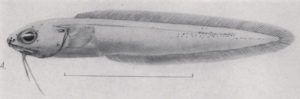

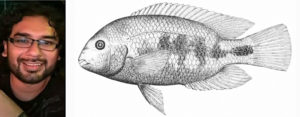

Apistogramma mendezi, from: Römer, U. 1994. Apistogramma mendezi nov. sp. (Teleostei: Perciformes; Cichlidae): description of a new dwarf cichlid from the Rio Negro system, Amazonas State, Brazil. aqua, Journal of Ichthyology and Aquatic Biology v. 1 (no. 1): 1-12.

19 December

Apistogramma mendezi and Astyanax chico

This Saturday, 22 December, marks the 30th anniversary of the assassination of Brazilian environmentalist, trade union leader, and human-rights advocate Francisco Alves Mendes, known the world over as Chico Mendes.

Born in 1944, Mendes began work as a rubber tapper at age 9. He developed a keen awareness of the injustice imposed by wealthy rubber barons who owned the rainforest lands. He organized plantation workers into labor unions, and persuaded tappers to form cooperative businesses in which they could sell the latex themselves, eliminating the bosses and other middlemen who kept most of the profit. The rubber barons, with deep ties to corrupt politicians and police departments, fought back, often with violence.

Mendes also realized that the rainforest itself was being destroyed, mainly through cattle ranching. When direct appeals to the Brazilian government failed, Mendes and his fellow tappers formed empates, or blockades, to prevent the destruction of trees. Ranchers retaliated. Even more violence ensued. Mendes feared for his life. In 1988, he said he would not live until Christmas. On 22 December, he was gunned down by a rancher whom Mendes had prevented from logging a protected area, while gaining a warrant for the rancher’s arrest for a murder committed elsewhere.

The assassination of Chico Mendes made international headlines, and led to an outpouring of support for the rubber tappers’ and environmental movements. Thanks in part to the media attention surrounding the murder, the Chico Mendes Extractive Reserve was created in the area where he lived.

Two fishes have been named in honor of Chico Mendes. Not surprisingly, both are from the South American rainforest. In 1994, Uwe Römer described Apistogramma mendezi (using Spanish instead of Portuguese spelling), a dwarf cichlid from the Rio Negro drainage of Brazil. Römer said Mendes “spoke vigorously for the preservation” of Brazilian rainforests and was murdered “just when his efforts were beginning to bear fruit.”

In 2004, Jorge Rafael Casciotta and Adriana Edith Almirón described Astyanax chico, a characin from the San Francisco River basin of Argentina and Bolivia. They described Mendes simply: “a defender of the Amazonian rainforest.”

UPDATE: A third species was named after Mendes in 2023: Tridens chicomendesi Henschel & Costa 2023, a trichomycterid catfish. The species occurs in Xapuri, Acre State, Brazil, where Mendes was born and lived.

Gobiomorus dormitor, from Bloch, M. E. and J. G. Schneider. 1801. M. E. Blochii, Systema Ichthyologiae Iconibus cx Ilustratum. Post obitum auctoris opus inchoatum absolvit, correxit, interpolavit Jo. Gottlob Schneider, Saxo. Berolini. Sumtibus Auctoris Impressum et Bibliopolio Sanderiano Commissum. i-lx + 1-584, Pls. 1-110.

12 December

Gobiomorus Lacepède 1800: A correction

This week, we’re righting a wrong.

Last week, while writing about the clingfish genus Gobiesox Lacepède 1800, we took another look at the sleeper goby genus Gobiomorus, described by Lacepède in the same publication (just two pages away). We took another look because Lacepède’s explanation of the name did not fit with our translation of the name. That’s when we realized we had confused the Greek adjectives moros and homoros. Failing to recognize that Lacepède had shortened homoros to its Latin cognate morus, we got the etymology wrong — although it fits quite nicely.

Gobio, it’s clear, refers to gobies. Morus, we initially we believed, was derived from moros, meaning dull, sluggish or stupid. Everything seemed to line up. Lacepède himself chose the epithet dormitor, Latin for “one who sleeps,” for the type species of the genus. Derived from dormeur, a vernacular used in the early 19th-century French colonies of South America, the name presumably refers to their seemingly lethargic behavior and is the source of the English vernacular “sleeper.” We found a precedent for moros in the Northern Gannet (Morus bassanus), named for the ease with which this bird can be caught. And even FishBase, which we often criticize for getting their etymologies wrong, reported that moros means silly or stupid.

However, Lacepède’s description remained a sticking point, for it seemed to provide a different explanation for the name: “They are, however, very close to the gobies, with which they have great similarities; and it is this kind of affinity or kinship that is designated by the generic name of gobiomore, neighbor or ally of the gobies, which I give them” (translation, italics in original).

Lacepède told us what we needed to know — “neighbor or ally of the gobies” — but we simply failed to connect morus with homoros, which means “neighborly.”

It seems the fish wasn’t “dull, sluggish or stupid.” We were.

5 December

5 December

Gobiesox Lacepède 1800

Here’s an example of a name that’s been used for 218 years without anyone — as far as we know — accurately explaining what it means. Proposed by Bernard-Germain-Étienne de La Ville-sur-Illon, comte de (count of) La Cepède, in the second volume of his Histoire naturelle des poissons, Gobiesox is the type genus of the clingfish family Gobiesocidae, which comprises its own order, Gobiesociformes.

Most clingfishes are small, shallow-water, bottom-dwelling fishes whose pelvic fins form an adhesive sucking disc that allow them to “cling” to rocks, seagrasses, barnacles, and other substrates and structure in strong currents and waves. Most are marine denizens, but seven or so species occur in fast-flowing rivers and streams of Central and South America.

The name “Gobiesox” is easily broken down. The first half appears to derive from gobius, or goby. And yes, one can see that clingfishes do superficially resemble their marine benthic neighbors, the gobies. But the “esox” part of the name is the real head-scratcher. “Esox” is a latinized Gaulish word for a large fish from the Rhine, possibly originally applied to a salmon, now applied to pikes and pickerel — large, torpedo-shaped freshwater gamefishes of Europe and North America that patrol the upper levels of the water column for smaller fishes and the occasional baby duck or water-borne mouse.

Suffice it to say, there is nothing pike-like about clingfishes. Even Jordan & Evermann, in their monumental Fishes of North and Middle America (1896), agree. Their etymology for the name reads: “Gobius; Esox ; the resemblances either to the goby or the pike being few or remote.” So why the name?

While Jordan & Evermann’s statement may be true, they apparently broke the First Rule of Ichthyonym Etymology, which is “Always consult the original description.” If they had, they would have seen that Lacepède had indeed explained the name. In describing Gobiesox cephalus, a freshwater species from Caribbean drainages of South America, he commented on what he perceived as its “many connections” (translation, i.e., close relationship) with gobies. He also specifically referred to the pike-like posterior placement of its dorsal fin, near the tail. This seems like a minor character on which to base a name, but that’s what Lacepède did.

What’s interesting to note is that Lacepède was seemingly unaware of this clingfish’s clinging ability. This may be because Lacepède did not have a specimen at hand, but instead based his description on a manuscript and illustration (which he had redrawn, shown here, a very bad likeness) provided by the French explorer and naturalist Charles Plumier (1646-1704). Had he known that the clingfish had adhesive pelvic fins, he may have coined a different, more relevant name.

Cover of Astounding Science-Fiction, December 1938, illustrating “The Merman.”

28 November

Vernon Brock, biologist and “Merman”

In 1938, Vernon E. Brock (1912-1971) was a Fishery Biologist in the Department of Research of the Fish Commission of Oregon. Little did he know that Vernon Brock was also a male mermaid in “The Merman,” a 1938 short story by science-fiction writer L. Sprague de Camp (1907-2000).

Brock achieved professional fame during his tenure with Department of Fish and Game for the Territory (later state) of Hawaii (1944-1959), as Director of the Bureau of Commercial Fisheries Biological Laboratory, Washington DC (1959-1963), and then as Director of the Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology (1963-1971). He was considered the leading authority on Pacific fisheries, especially the biology of tuna. In 1960, he published, with William Gosline, the first edition of Handbook of Hawaiian Fishes, which continues to be a standard reference today. He also published on reptiles and birds.

Eight fish species have been named after Brock; two are considered valid today: a pipefish (Syngnathidae), Halicampus brocki (Herald 1953), from the southeast Indian and western Pacific oceans, and Argyripnus brocki Struhsaker 1973, a deepsea bristlemouth (Sternoptychidae) from the Hawaiian Islands. In addition, the labrid blenny genus Brockius Hubbs 1953 is named for Brock, who collected the type species, B. striatus, and developed a collecting technique to sample its habitat (rocky bottom slightly below low-tide line).

Apparently unbeknownst to Brock, L. Sprague de Camp created a second, fictional Vernon Brock — an aquarist at the New York City Aquarium who, in addition to his normal duties, was working on an organic compound to turn vertebrate lungs into gills. During an experiment with alligators, the fictional Brock breaks a flask and inhales vapors from the compound. Overcome, he falls into a shark tank, whereupon he discovers he can now “breathe” water but not air. Unable to leave the tank, he uses a remora to scrawl messages on the tank’s glass and competes with the sharks for food. He grows delusional because of the “constant muscular effort required to work his lungs.” Believing he is a fish and that an aquarium visitor wants to eat him, he attacks the glass with a pocket knife until it gives way. Brock recovers in the hospital, but learns that the Aquarium is facing a lawsuit from a man who nearly drowned from the water Brock let out of the tank. Brock convinces the man to drop the suit. The man, a former circus acrobat, agrees to use Brock’s discovery to exhibit himself for money as a Merman.

Science-fiction scholars say the story is a forerunner to the concept of genetic engineering, a major theme in subsequent science-fiction tales. Others credit the story as a possible influence on water-breathing comic book superheroes such as Sub-Mariner and Aquaman.

L. Sprague de Camp was reportedly mortified to learn that a real Vernon Brock existed who actually worked with fishes. According to one account, de Camp worried that the real Brock would sue for defamation. Alas, he did not. Upon learning of his water-breathing fictional alter ego, Vernon Brock the man — not the Merman — simply laughed.

Dandara, from O Globo, a Brazilian newspaper.

21 November

Crenicichla dandara Varella & Ito 2018

Yesterday, 20 November, was Dia da Consciência Negra — Black Awareness (or Consciousness) Day — in Brazil, an annual celebration in which the black community, mainly people of African descent, celebrate their worth and contribution to the country. The date is significant for it commemorates the 20 November death of Zumbi, an anti-slavery warrior, in 1695, and now a national hero in Brazil.

According to legend, Zumbi and his wife Dandara fiercely defended the community of Palmares, a safe haven for escaped slaves in the coastal state of Alagoas, Brazil. Dandara was skilled in capoeira, a Brazilian martial art, and fought many battles alongside men against Portuguese and Dutch colonialists and enslavers. She was arrested on 6 February 1694. Refusing to return to slavery, she committed suicide.

Today, Dandara is celebrated as a symbol of the struggle against racism and the exploitation of black women. Earlier this year, a new species of pike cichlid from the Rio Xingu basin of Brazil was named in her honor.

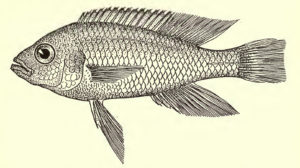

Ptychochromis ernestmagnusi, holotype, 146.6 mm SL, adult male. Freshly captured specimen illustrating adult coloration in life. Photo by Paul Loiselle. From: Sparks, J. S. and M. L. J. Stiassny. 2010. A new species of Ptychochromis from northeastern Madagascar (Teleostei: Cichlidae), with an updated phylogeny and revised diagnosis for the genus. Zootaxa No. 2341: 33-51.

14 November

Ptychochromis ernestmagnusi Sparks & Stiassny 2010

Read the etymology section of this Malagasy cichlid’s formal introduction to science and you will know that it’s named in honor of Mr. Ernest Magnus of Berlin, Germany, and New York City. You will know that it’s named at the request of the family of Dr. Rudolph G. Arndt. And you will know that Dr. Arndt’s “support of ichthyological exploration and research at the American Museum of Natural History is gratefully acknowledged.” What you won’t know is the moving family saga of love and pain behind the fish’s name.

Rudolf G. Arndt — his name is spelled “Rudolf,” not “Rudolph,” as incorrectly stated in the description — is Professor Emeritus of Biology at Stockton University in New Jersey. He donated money to the American Museum of Natural History, which helped fund Sparks’ and Stiassny’s research into Malagasy cichlids. In many such cases, the recipients of the donation name the new species after their benefactor. But Dr. Arndt requested that the new cichlid be named after his uncle, Ernest Magnus (1908-1983), instead. Why? We asked Dr. Arndt and were quite moved by the story he shared, which we share with you here, in his own words:

Ernest Magnus is one of two brothers of my mother, Mrs. Meta Magnus Arndt. All of my nuclear and extended family are immigrants to America, arriving about 1930 (my two uncles) and 1950 (myself and my sister and my parents). All of us were born in Berlin. My uncle Ernest Magnus was very instrumental in helping my family survive in Berlin after World War II by sending us ‘Care’ packages containing clothing and food items and providing moral support. Further, he was instrumental in contacting his New York Congressman to try to obtain/expedite paperwork during the application process by my father to the US government to allow us to emigrate to America. Further yet, he and his wife, Hattie, both very loving and friendly people, met us at the dock at which we arrived in Manhattan by boat from Hamburg, Germany, after a harrowing two-week crossing of the North Atlantic in mid-March 1950. To continue, uncle Ernest allowed us four to live in his two-bedroom home in Queens, New York City, for our first eleven months in America and also fed us and introduced us to our new surroundings. He was our sponsor in our move from the Old World to the New, which in those days you had to have in order to be able to enter the US. After that, we found an apartment and left his home.

It pains me to say this, but my father was very opinionated about many things, so much so that he was a tyrant. Despite all of the help we had from my uncle Ernest, within about two years, perhaps three, after our arrival in New York my father was not on speaking terms with my uncle and his wife and without ever saying it to us directly, forbade his wife and my sister and me to speak or associate with uncle Ernest and aunt Hattie (although we did so very occasionally and on the sly). This was a great loss to everyone, which I feel even today, except to my father (it was a loss to him also, but he did not recognize this).

Therefore, because of his love and many kindnesses to me and my family for so long I wanted to show my appreciation to him by memorializing him in the species name of an organism (unfortunately by the time I did this my uncle Ernest and aunt Hattie were both deceased). This could never repay his kindnesses nor compensate him for his so-needless suffering at the hands of his brother-in-law, my father, but it was my weak attempt to do so.

The final words of Dr. Arndt’s reminiscence say it all: “I still owe my uncle!”

Wolfgang Klausewitz circa 2012.

7 November

Klausewitzia Géry 1965

For the 21 February 2018 “Name of the Week,” our friend Erwin Schraml interviewed German ichthyologist Wolfgang Klausewitz to find out the meaning of the goby generic name Lotilia. This past weekend we learned that Dr. Klausewitz passed away on 31 August after a short stay in the hospital. He was 96.

Born 20 July 1922 in Berlin, Klausewitz always knew he wanted to be a zoologist. His plans were put on hold during World War II, when he was drafted by the Nazis, deployed in North Africa, and ended up as an American prisoner of war. While he was a recruit, he attended a lecture by marine explorer Hans Hass — the Austrian equivalent of Jacques Cousteau — about his dive adventures in the Caribbean. He was enchanted by Hass’ exploits. Little did he realize that they two would later become dive buddies, collaborators and very close friends.

Upon his release in 1946, Klausewitz visited the Senckenberg Museum of Nature in Frankfurt, where he was advised not to pursue zoology in post-war Germany. At some point he met a young lady named Rita, who urged him not to give up on his dream of becoming a zoologist. Rita eventually became his wife.

In 1946, Klausewitz enrolled at Frankfurt University and began studying biology. He helped rebuild the university’s buildings, which had been damaged during the war, and volunteered at the Senckenberg Museum, beginning a lifelong relationship with that institution. Klausewitz earned his Ph.D. in 1949 with a thesis on the lymphatic system and blood cells of amphibians. He continued to work in herpetology until in 1954, when he was permanently employed as Head of the Senckenberg Fish Section.

Dr. Klausewitz specialized in the taxonomy, systematics and biogeography of Red Sea and Indian Ocean fishes, particularly eels. He dove often with Hans Hass, and became the “fish expert” in the many documentaries Hass produced for German television. These programs reportedly featured the first underwater footage ever shown on TV. These expeditions also gave Klausewitz what was then the novel opportunity to complement traditional morphological studies of preserved specimens with observations of living fishes in the wild.

In the 1970s, when pollution and conservation became issues of concern, Dr. Klausewitz shifted his focus to ecological studies of freshwater fishes in German rivers, and to creating museum displays and programs on biodiversity and environmental awareness. He retired in 1987 but remained active as an emeritus in ichthyology and the history of natural science.

By our count, Dr. Klausewitz described or co-described over 50 fish taxa, most of which remain valid today. Seven species have been named in his honor, five of which remain valid: two conger eels (Gorgonia klausewitzi and Heteroconger klausewitzi), a headstander (Leporinus klausewitzi), a goby (Lotilia klausewitzi), and a deepwater serranid (Plectranthias klausewitzi). In 1965, Jacques Géry proposed the crenuchid (Characiformes) genus Klausewitzia in honor of their friendship. Géry named the only species in the genus, Klausewitzia ritae, after Klausewitz’s beloved wife, who died in 1995.

Note: Much of the biographical information about Dr. Klausewitz came from an obituary and appreciation written by his successor Friedhelm Krupp at https://aqua-aquapress.com/ .

31 October

Five ghostly names for Halloween

Hydrolagus melanophasma James, Ebert, Long & Didier 2009 — Most ghosts in popular culture are pictured as white, drained of life and color. This ghost, however, is black. The Eastern Pacific Black Ghostshark occurs in the eastern North Pacific from California to Chile. The first part of its specific name, melano-, means black and refers to its color its in life. The second part of the name phasma, means ghost or specter, alluding to the vernacular “ghostshark” given to many members of the family Chimaeridae because of their pallid coloration and creepy appearance.

Hyphessobrycon negodagua Lima & Gerhard 2001 — This tetra from the Upper Paraguaçú River basin of Brazil is named after Nego D’água, a legendary man-like creature said to dwell in the bottoms of Brazilian rivers and torment inattentive fishermen at night. He takes fish out of hooks, breaks fishing lines, pierces nets, and scares people on boats. He is even known to steal children who bathe too far from the banks.

Corydoras lymnades Tencatt, Vera-Alcaraz, Britto & Pavanelli 2013 — This catfish from the Rio São Francisco basin of Brazil is named after the limnads, small creatures in Greek mythology derived from goblins. They can see the bottom of a man’s soul and take the form of his most beloved person. The name refers to its close resemblance in color (but not in size) to the larger Corydoras garbei.

Otophidium chickcharney. From: Böhlke, J. E. and C. R. Robins. 1959. Studies on fishes of the family Ophidiidae.–II. Three new species from the Bahamas. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia v. 111: 37-52, Pl. 5.

Otophidium chickcharney Böhlke & Robins 1959 — Chickcharnies are legendary ghosts of the Bahamas, where this cusk-eel is endemic. It is said to live in forests, is both furry and feathered, stands about a meter tall, and resembles an ugly owl. The name refers to this cusk-eel’s pallid coloration and the appearance of its large eyes when viewed from above

Pallidochromis tokolosh Turner 1994 — This Malawian cichlid is named for the tokolosh, a malevolent spirit in languages of central and southern Africa. It refers to the long snout, bulging eyes and sagging pot-belly of specimens trawled from deep water as represented in carvings made around Lake Malawi.

Ophiclinus ningulus, at Port Hughes, South Australia, 01 March 2014. Source: Robert Paton / Atlas of Living Australia, http://fishesofaustralia.net.au/home/species/1107

24 October

The fish named after … nobody

This fish is so unremarkable, it’s named after nobody. Literally.

In their 1980 monograph, “Revision of the clinid fish tribe Ophiclinini, including five new species, and definition of the family Clinidae”, Anita George and Victor G. Springer, described a new species of snake blenny from southern Australia, Ophiclinus ningulus. They assigned it the specific epithet “ningulus,” which is Latin for “nobody.” The name refers to its “lack of distinctive characters that might otherwise serve as a basis for a scientific name.”

In other words, the most distinguishing feature of this blenny is that not a single character distinguishes it from other members of its genus. Instead, this species is best identified through a combination of characters:

- dorsal-fin spines 42-48

- interradial membranes of anal fin incised

- cirrus absent on tube of anterior nostril

- all pore positions of supratemporal sensory canal with simple pores

- ventroanteriormost preopercular sensory canal pore position with single pore

- lateral-line pores 12-15

- dorsal-fin origin at vertical over posterior 1/8 of opercle length or just posterior to opercle

- predorsal bones 1

Its common name is Variable Snake Blenny. The “snake blenny” part comes from the genus Ophioclinus. Coined by Castelnau in 1872, the name translates as ophis (snake) and Clinus (type genus of family, from ancient Greek name for blennies). It refers to their elongate, snake-like bodies. We’re not sure what inspired the “Variable” part of the name. It seems ichthyologists struggled in coming up with an appropriate vernacular because the literature records two abandoned alternatives: Distinctiveless Snake Blenny and Featureless Snake Blenny.

In our opinion, “Nobody Blenny” would have been a relevant and memorable name.

Photo by Luiz Rocha. © California Academy of Sciences.

17 October

Tosanoides aphrodite Pinheiro, Rocha & Rocha 2018

Two of the ichthyologists who described this new species of anthias while diving at 120 m were so enchanted by its beauty, they didn’t notice the Six-gill Shark (Hexanchus griseus) swimming over their heads — a breathtaking moment captured on video.

“This one is without a doubt the most spectacularly colored fish I’ve ever described,” says Luiz Rocha, Associate Curator and Follett Chair of Ichthyology at the California Academy of Sciences.

Rocha and his collaborators discovered the fish at St. Paul’s Rocks, an archipelago of small islets located around 940 km from northeastern Brazil. It’s the only known species of the genus — heretofore known only from the Pacific — to occur in the Atlantic.

The DayGlo brilliance of the male — with its pink-and-yellow body and bright green fins — inspired the ichthyologists to name it after Aphrodite, the goddess of love and beauty.

“The beauty of the Aphrodite anthias enchanted us during its discovery,” they wrote in their description, “much like Aphrodite’s beauty enchanted ancient Greek gods.”

10 October

Glyphis garricki Compagno, White & Last 2008

One of the world’s leading elasmobranch biologists, J.A.F. (Jack) Garrick, passed away on 30 August. He was 90 years old.

Dr. Garrick was a professor at Victoria University of Wellington from 1950 to 1990. His primary interest was in the taxonomy of sharks and rays, but he also carried out the first exploratory deep-sea sampling using specially adapted cone nets, baited traps and longlines, regularly to depths greater than 2000 m. Many new and rare species were obtained by use of these innovative techniques. In addition, he was responsible for the discovery of the first New Zealand specimens of Orange Roughy (Hoplostethus atlanticus) in 1957 (forming the basis of a multi-million dollar fishery).

Dr. Garrick named or co-named two shark genera, four shark species, and four ray species. He also co-named the Flabby Whalefish, Gyrinomimus grahami. Not surprisingly, Dr. Garrick has been honored in the names of six fish species: four sharks, one ray, and one eelpout. Perhaps the most famous fish named after Garrick is the Northern River Shark, Glyphis garricki. Found in scattered tidal rivers and associated coastal waters in northern Australia and in Papua New Guinea, the shark was featured on the Animal Planet TV program “River Monsters” in 2012:

The authors of G. garricki credit Garrick for discovering this shark in the form of two newborn males from Papua New Guinea. They thank him for supplying radiographs, morphometrics, drawings and other details of these specimens (since lost) to the senior author. In addition, they acknowledge Garrick’s 1982 revision of the requiem shark genus Carcharhinus.

Dr. Garrick is survived by four children, 10 grandchildren, and three great-grandchildren.

Swallowtail Shiner, Miniellus procne. Courtesy: New York State Department of Environmental Conservation.

3 October

Miniellus Jordan 1888 actually dates to 1882

Later this month, we expect to release a major revision of the Order Cypriniformes (carps, minnows, barbs, suckers, loaches, etc.), with several new families and subfamilies, many new genera and species, and dozens of other taxonomic changes. Among these updates will be the addition of three North American minnow genera originally proposed in the 19th-century, sunk into synonymy during the 20th-century, and brought back to life in phylogenetic studies completed here in the 21st. These resurrected genera are Hudsonius Girard 1856, Graodus Günther 1856, and Miniellus Jordan 1888.

While researching the etymologies of these names, we made an unexpected discovery:

Miniellus — long believed to date from David Starr Jordan’s A Manual of Vertebrate Animals of the Northern United States (5th ed., 1888) — actually dates to a “Report on the Fishes of Ohio” he wrote for the Geological Survey of Ohio in 1882.

What’s even more surprising is that it was Jordan himself — usually a stickler for taxonomic and bibliographic accuracy — who solidified the younger work as the original (and therefore official) publication of the name. He did so in the final installment of his four-part monograph The Genera of Fishes (1917-1920), a canonic contribution to the stability of ichthyological nomenclature. There Jordan unambiguously established three facts about the name: 1) It dates to page 56 of the 5th edition (1888) of his Manual; 2) the type species is Hybopsis (originally Hybognathus) procne, described by Cope in 1865; and 3) Jordan regarded Miniellus as a junior synonym of Alburnops Girard 1856. So authoritative was Jordan’s Genera of Fishes (it was reprinted in 1968) that future ichthyologists accepted the 1888 date for Miniellus without further investigation. Indeed, why question Jordan’s citation for a name that he himself proposed?

And so I turned to page 56 of Jordan’s 1888 Manual hoping to learn the etymology of the name Miniellus from the man who coined it. Instead of a description, however, all I found was a three-line dichotomous key in which Miniellus is diagnosed as a subgenus of Notropis with a complete (vs. incomplete) lateral line.

Hoping that Jordan elaborated on the name in a later publication, I command-F-searched for “Miniellus” in the “Jordan, David Starr” folder of my hard drive. I was surprised to see an earlier publication in the search results — the Geological Survey of Ohio publication from 1882. I opened the PDF, searched for “Miniellus” within the text, and landed on page 842, where Miniellus was defined as one of three subgenera of Hudsonius, distinguished by its “rather large head; dorsal fin inserted over ventrals; teeth one-rowed; scales large, not closely imbricated; fins plain.”

So the big question is: Why did Jordan abandon his own 1882 publication, with its more detailed diagnosis of Miniellus, for the thin three-word diagnosis (“Lateral line complete”) published in 1888? Your guess is as good as mine.

What’s clear is that Jordan didn’t know what to do with Miniellus. He proposed it as a subgenus of Hudsonius in 1882 (but note that Jordan submitted his manuscript in 1878). In 1883 (sometimes dated 1882), he listed it as subgenus of Cliola (now considered a synonym of Pimephales). In 1885, he moved it into the synonymy of Alburnops. In 1896, it’s a synonym of Notropis. It’s back into Alburnops in 1920. And finally, in 1930, a year before his death, Jordan treated Miniellus as a synonym of Hybopsis.

Jordan never explained the etymology of Miniellus, but we can guess what it means. “-iellus” is a diminutive suffix, usually connoting smallness or insignificance. “Mini-” is almost certainly derived from “minnow.” Therefore, the name probably means “small minnow” (or “minnie” in American vernacular). This interpretation is supported by the disparaging tone of his original 1882 description of the genus.

Miniellus includes “small, plain species,” Jordan wrote. “These are the smallest and most insignificant of American Cyprinidae …”.

26 September

Pseudocrenilabrus philander (Weber 1897)

Pseudocrenilabrus philander, courtesy Republic of South Africa, Department of Water and Sanitation, River Health Programme, Fish of the Umngeni River.

When a fish has a name like philander, it’s easy to assume it’s just that — a philanderer, i.e., a womanizer, a ladies’ man, a Don Juan, rake, tomcat, skirtchaser, etc. And that’s what meteorologist-turned-ichthyologist Rex A. Jubb (1905-1987) assumed in his 1967 book Freshwater Fishes of Southern Africa, wherein he stated that this cichlid’s name “probably refers to the polygamous tendencies of the male which is very beautiful in his breeding dress.”

The word “probably” indicates that Jubb was taking a guess. Our guess is that he’s probably wrong.

German-Dutch ichthyologist Max Weber (1852-1937) described this cichlid from Natal, South Africa, in 1897. He, of course, did not explain the etymology of the name nor why he selected it (hence our discussing it here). We do know that philander is derived from philos, meaning friend or lover, and andros, of man or men. It literally means “friend of man” but is often interpreted as “loving man” (i.e., a man who loves).

We also know that Weber did not describe the male’s breeding colors, which appears to discount Jubb’s explanation of the name. Weber described the color as olive brown, darker on the back and head, lighter on the belly, with a heavily washed dark band on the sides. Hardly the courtship colors of a promiscuous playboy!

Weber did, however, note that the cichlid appears to be a mouthbrooder. The first specimen he caught and dropped in alcohol immediately spat out about 20 live young almost 1 cm in length. He caught another specimen with 30 fry in its mouth, 6 mm in length, still with their yolk sacs. Weber did not mention the sex of these specimens, but aquarium observations have confirmed that it’s the mother who broods the young.

Based on Weber’s observation of adult (female) cichlids carrying their young, we suspect that philander is alluding to the opossum genus Philander, or to a particular opossum species, Caluromys philander. Opossums are marsupials in which the mothers carry their young in pouches and then on their backs.

Why are opossums are called Philander? We cannot say for sure. Although the name was applied to opossums by Linnaeus in his 1758 Systema Naturae (the starting point of zoological nomenclature), its first usage appears to date to Albertus Seba in 1734. Seba was a Dutch pharmacist who assembled a large “cabinet of curiosities,” including an opossum from Ambon Island, Indonesia. In the published catalog describing the contents of his cabinet, he notes that his opossum was called “pelandor Aroe” in Malaysia, or, per his translation, the “rabbit of Aroe” (referring to present-day Aru Islands).

Might “philander” be a variant spelling of “pelandor”? We thought so at first. But we now suspect that “pelandor” is a misspelling or typo of “pelandok,” the Malaysian name for a mouse-deer (Tragulus), which vaguely resembles an opossum with long deer-like legs.

We’d like to keep researching the etymology of opossums, but we need to get back to fish.

Collection site of Copionodon elysium, Riacho Águas Claras, near Morrão, Bahia, Brazil. From: de Pinna, M., R. Burger and A. M. Zanata. 2018. A new species of Copionodon lacking a free orbital rim (Siluriformes: Trichomycteridae). Neotropical Ichthyology v. 16 (no. 2) (e170146): [1-9].

Copionodon elysium de Pinna, Burger & Zanata 2018

This Friday, 21 September, is the United Nations’ International Day of Peace. The following is one of the loveliest, most tranquil fish names of the 26,300+ we’ve researched so far.

Copionodon elysium is a recently described (June) trichomycterid catfish known only from riacho Águas Claras, a stream of approximately 6 km, in the rio Paraguaçu basin of the Diamantina Plateau in Bahia State, Brazil. The specific epithet is named for the Elysean Fields of Greek mythology, a place or condition of ideal happiness or perfect bliss. According to the authors, the name alludes to its habitat (shown here), described as a “scenic pristine place” shared with a single other fish species (Astyanax sp.) and no fish predators.

So even the fish live in peace.

12 September

12 September

Mary Henrietta Kingsley (1862-1900)

What if you decided to leave your home and family to collect fishes in Africa? And what if you had no idea how to get around Africa and didn’t speak any of its languages? And what if you had no formal education in the sciences? And what if you lived during Victorian times, when travel to places like Africa was fraught with extreme danger — long sea voyages, disease, violent natives, venomous creatures in the bush?

And what if you were a woman, traveling alone?

None of this daunted Mary Henrietta Kingsley. Born in England in 1862, she refused to live the life of a genteel Victorian lady. Instead, when her ailing parents died within months of each other, she took her modest inheritance and booked a two-week steamboat trip to Sierra Leone in 1893.

Mary lived with the locals, who taught her survival skills for life in the wilderness. (Confused to see a white woman traveling alone, they often asked where her husband was.) She returned to England in December and spent the next year acquiring the supplies and financial support to mount a more elaborate expedition. She wanted to collect. Reptiles, insects, shells, grasses, ethnographic artifacts. But mostly fishes.

While many remained skeptical of Kingsley’s skills and ambitions, ichthyologist-zoologist Albert Günther of the British Museum was clearly impressed. Knowing that she was planning to visit the interior of Gabon, he suggested that she focus on the “mighty” Ogowe River. And she did.

“The means of preserving and transporting the specimens were naturally limited,” Günther wrote, “as Miss Kingsley travelled alone with a native crew; besides, whilst traversing the region of the rapids, which extends over some hundred of miles, the upsetting of her canoe was a matter of frequent occurrence. Nevertheless she succeeded in bringing home in excellent condition a collection of eighteen species of Reptiles and about sixty-five species of Fishes, which will be enumerated or described in this paper, besides a number of other, especially entomological, specimens.”

Günther named five fishes after her, three of which remain valid today: the mormyrid (or elephantfish) Paramormyrops kingsleyae, the African tetra Brycinus kingsleyae, and the climbing gourami Ctenopoma kingsleyae. Boulenger named two cichlids after Kingsley: Chromidotilapia kingsleyae in 1898 and Pelmatolapia mariae in 1899. In 2013, Decru, Vreven & Snoeks added to Kingsley’s legacy by naming Hepsetus kingsleyae, an African pike characoid, in her honor.

Kingsley became something of a celebrity upon her return to England. She wrote two bestselling books about her travels. She gave lectures. And she angered the Church of England by criticizing missionaries for their attempts to corrupt African religions. Her lectures and writings helped Europeans better understand the impact (both good and bad) British imperialism in Africa and the little-known lives of native Africans.

Kingsley returned to Africa in 1899 to collect fishes from the Orange River in South Africa. Shortly thereafter, the Boer War broke out. Horrified by the war, which she regarded as imperialism run mad, Kingsley volunteered to work as a nurse in Cape Town, tending to injured Boer prisoners of war.

“All this work here, the stench, the washing, the enemas, the bedpans, the blood, is my world,” she wrote to a friend.

The confines of a prison hospital proved more hazardous than the dangers of the wild. Two months later she contracted typhoid fever. On 3 June 1900, Mary Kingsley died at the age of 37.

From: Valdesalici, S. and K. Kardashev 2011. Nothobranchius seegersi (Cyprinodontiformes: Nothobranchiidae), a new annual killifish from the Malagasi River drainage, Tanzania. Bonn Zoological Bulletin v. 60 (no. 1): 89-93.

5 September 2018

Lothar Seegers (1947-2018)

German ichthyologist, aquarist and photographer Lothar Seegers passed away on August 6. Dr. Seegers was well-respected in both scientific and aquarium circles. He specialized in the fishes of East Africa, describing or co-describing killifishes (10 names), catfishes (8), cichlids (7), knerias (3), and minnows (2). He also described several killifish taxa (11) from the Amazon basin of Peru.

Dr. Seegers is honored in the names of two African killifishes. Aphyosemion (Diapteron) seegersi, described by his friend and occasional collaborator Jean Huber, is known only from a small brook, along a bike road, under forest cover in the upper Ivindo drainage system of northern Congo. Huber dedicated this species to Seegers “as a sign of my friendship and my admiration for his remarkable research” (translation) into the egg surface structures of killifishes. In 2011, Stefano Valdesalici and Kiril Kardashev described Nothobranchius seegersi (shown here from the original description) from a seasonal pool in the Malagarasi River drainage of Tanzania. “The species is named in dedication to its first collector,” the authors wrote, “the enthusiastic aquarist and ichthyologist Lothar Seegers, Germany.”

Four of Dr. Seegers’ publications grace our library: his 1996 monograph The Fishes of the Lake Rukwa Drainage (1996); his two-volume Aqualog series Killifishes of the World: Old World Killis (1997), and the very readable, informative and colorful Catfishes of Africa (2008).

29 August 2018

Microspathodon Günther 1862

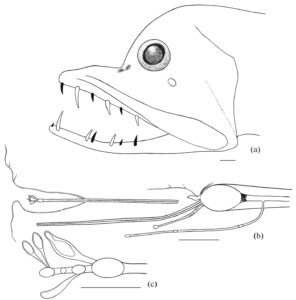

Confirming the etymology of this name did not involve a dictionary. It involved pulling a preserved specimen out of a jar and looking at its teeth.

Albert Günther proposed this genus of American damselfishes, now with four species, in 1862. He did not provide an etymology, but the name is easily broken down: micro = small, spath = a broad blade (e.g., spatula, chisel), odon = tooth. Trouble is, Günther did not provide much of a description. He proposed the name in a dichotomous key, saying only that the teeth on its upper jaw are “very fine and moveable.” So while “very fine” matches the “micro” part of the name, he said nothing about their shape. In fact, we found nothing in any subsequent account of the genus that described its dental morphology. Why name a genus for a particular character and not mention that character in the description?

American ichthyologists David Starr Jordan and Barton Warren Evermann took us down a different etymological path. In their monumental Fishes of North and Middle America (1896-1900), they said that spath = spathe, or sheath. They too, like Günther, described the teeth as moveable, but, frustratingly for us, did not describe anything sheath-like about them. But since these guys knew their Greek and Latin, we took them at their (pun not intended) word. We eventually found a potential anatomical clue in a 1967 account of Microspathodon teeth and drafted this provisional etymological explanation:

micro-, small; spathe, sheath (per Jordan and Evermann 1898); odon, tooth, proposed briefly in a key, allusion not explained nor evident, presumably referring in some way to “very fine” moveable teeth in upper jaw of M. chrysurus [type species]; perhaps “sheath” refers to how those teeth are anchored by relatively loose connective tissue within an unusual anterio-ventral fossa on the premaxilla (as described by Ciardelli 1967)

Still, we suspected that our explanation was not quite right. So we brought in an expert, damselfish taxonomist Gerald R. Allen, former curator of the Western Australian Museum in Perth and now a team leader conducting coral reef-fish surveys for Conservation International. Dr. Allen was certain that “spath” referred to the flat shape of its teeth. So he had his son Mark, also an ichthyologist and now collection manager at the Western Australian Museum, check their collection of Microspathodon chrysurus specimens. The younger Dr. Allen photographed the teeth (shown here) and the elder Dr. Allen provided this note:

The photo “shows [that Microspathodon] does indeed have small chisel-like teeth, which fits the Greek definition (‘any broad blade’) nicely. So hopefully you can put that one to bed.”

22 August 2018

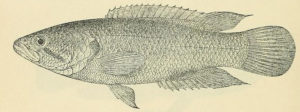

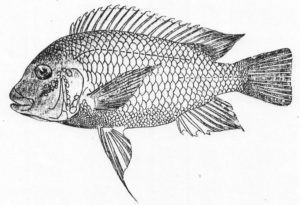

Haplochromis brownae Greenwood 1962

When we posted the etymology of this Lake Victoria cichlid on 22 July 2018, we had no idea whom P. Humphry Greenwood named it after. Here was what we posted:

matronym not identified, nor can identity be inferred based on available information; de Medeiros 2009 states that name refers to its brown body color but we doubt this interpretation

The de Medeiros citation, by the way, comes from The Cichlidroom Companion entry for the species:

Haplochromis brownae. From: Greenwood, P. H. 1962. A revision of the Lake Victoria Haplochromis species (Pisces, Cichlidae). Part V. Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History) Zoology v. 9 (no. 4): 139-214, Pl. 1.

Now we’ve learned from our good friend Erwin Schraml that Greenwood named this cichlid after a fish ecologist he worked with at Lake Victoria in Uganda in 1950 or 1951. Her name was Margaret (Peggy) Brown, a visiting scientist at the East African Freshwater Fisheries Research Organization (Jinja, Uganda, on the shore of Lake Victoria), where Greenwood worked from 1950 to 1957.

Schraml’s source was a personal communication with tropical-fish ecologist Rosemary Lowe-McConnell (1921-2014), who was also in Uganda at the time. Brown was her friend and collaborator in East Africa. They later studied fish together in the Brazilian Amazon.

Margaret Brown turned out to be an influential fish ecologist. Born in India to British parents in 1918, she received her Ph.D. in zoology in 1945. Her dissertation described the growth physiology of Brown Trout (Salmo trutta), a seminal work that is still cited today. In 1955, she married entomologist George C. Varley and published under her husband’s name. Her 1957 book Physiology of Fishes is said to have “effectively created” the field of ecophysiology.

Margaret Brown turned out to be an influential fish ecologist. Born in India to British parents in 1918, she received her Ph.D. in zoology in 1945. Her dissertation described the growth physiology of Brown Trout (Salmo trutta), a seminal work that is still cited today. In 1955, she married entomologist George C. Varley and published under her husband’s name. Her 1957 book Physiology of Fishes is said to have “effectively created” the field of ecophysiology.

In 1969, Dr. Varley (née Brown) made an even bigger name for herself as one of the founding members of The Open University, a public distance learning and research university, and one of the biggest universities in the UK for undergraduate education. She passed away in 2009 at the age of 90.

We’re so glad that Erwin Schraml chatted with Rosemary Lowe-McConnell regarding the name of this cichlid. If not, the story of its etymology may have been lost forever.

Hazeus ingressus. From: Engin, S., H. Larson and E. Irmak. 2018. Hazeus ingressus sp. nov. a new goby species (Perciformes: Gobiidae) and a new invasion in the Mediterranean Sea. Mediterranean Marine Science v. 19 (no. 2): 316-325.

15 Aug. 2018

Hazeus ingressus Engin, Larson & Irmak 2018

Several fish species have been described from aquarium specimens, with their type localities not identified and their distributions in the wild (at the time) only very generally known. This recently described goby is the only fish species we know of described from an invasive population — a fact reflected in its name — with its natural distribution hypothesized but not yet confirmed.

This goby was discovered in June 2015 in Aliosman Bay, along the northern Levantine coast of southwestern Turkey on the Mediterranean Sea. Based on a morphological and genetic analyses, ichthyologists realized they had a species of Hazeus on their hands, and a new one at that. Proposed by Jordan & Snyder in 1901, Hazeus is a small genus of gobies heretofore known only from the western Pacific (Japan, Taiwan, Philippines, Indonesia), the western Indian Ocean, and the Red Sea (Israel). So how did an Indo-Pacific goby get into the Mediterranean?

Since one species of Hazeus (H. elati) occurs in the Red Sea, the researchers hypothesized that their Mediterranean goby originated there as well. In fact, 10 other Red Sea gobies have established populations in the Mediterranean, making their way north through the Suez Canal, the artificial waterway that connects the two seas. An expanded and widened Suez Canal was opened in 2015, which is expected to increase the number of Red Sea migrants into the Mediterranean with negative consequences on the resident fish fauna.

The new goby’s name, ingressus, is derived from the Latin word meaning “enter, step or go into,” referring to its entering the Mediterranean. (The generic name Hazeus is a latinization of haze, a Japanese word for small goby.)

The goby’s presumed migration from the Red Sea to the Mediterranean via the Suez Canal is called “Lessepsian migration,” named after the French diplomat, Ferdinand de Lesseps, who supervised the construction of the canal. “Lessepsian” is featured in the name of the recently described (2015) lizardfish Saurida lessepsianus, another Lessepsian migrant. Unlike Hazeus ingressus, however, ichthyologists were able to confirm its natural occurrence in the Red Sea.

Heros notatus. From: Schomburgk, R. H. 1843. The natural history of fishes of Guiana. Part II. In: W. Jardine (ed.) The Naturalists’ Library. Vol. 5. W. H. Lizars, Edinburgh.

8 August 2018

Heros Heckel 1840

Heros is a small genus (five species) of cichlids distributed widely in Atlantic drainages of South America, including much of the Amazon and Orinoco basins, Tocantins drainage, and coastal drainages of the Guianas. The name was proposed by Austrian ichthyologist Johann Jakob Heckel (1790-1857) in his 1840 journal article, “Johann Natterer’s neue Flussfische Brasilien’s nach den Beobachtungen und Mittheilungen des Entdeckers beschrieben (Erste Abtheilung, Die Labroiden)” (“Johann Natterer’s new river fish of Brazil described according to the observations and communications of its discoverer [part one, the labroids”]). Heckel was the first to seriously study cichlids and revise the family. Many well-known cichlid genera (e.g., angelfish, Pterophyllum; discus, Symphysodon) date to this paper.

The significance of Heckel’s selection of Heros as the name for the genus has eluded ichthyologists since its coinage. The word likely means “hero” or “heroine” but Heckel provided no clue as to what he found heroic about these cichlids. A potential clue may be in the classical use of the word hero, meaning “protector,” “defender” or “guardian.” Was Heckel referring to the cichlids’ parental care of their young?

We asked the neotropical cichlid expert Sven O. Kullander if our explanation had any merit. His answer was, basically, no. Heckel probably knew very little about the natural history of the cichlids he described, Dr. Kullander said. Heckel’s only source of information were the notes of explorer Johann Natterer (1787-1843), who collected most of the cichlids described in Heckel’s paper. Kullander examined Natterer’s notebook, which still exists, but found no information beyond what Heckel had already cited. Natterer kept a diary but unfortunately it appears to have been destroyed in a fire during the Austrian revolution of 1848.

Another possible explanation comes from the works of Homer, in which “hero” is reserved for the chief warriors and captains. Might the large number of spiny anal fin rays—a feature Heckel used to distinguish Heros from its closest relatives—make Heros more “warrior-like” than the other cichlid genera Heckel described in the same paper?

“I cannot say if the spiny anal fin is particularly heroic,” Dr. Kullander told us. “But there may be some meaning here that was more obvious to people with knowledge of classical Greek mythology.”

Xyrauchen texanus, Razorback Sucker. Photograph by Mark Fuller. Courtesy: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

1 August 2018

The Texan fish that’s not from Texas

There are many misnomers in fish nomenclature. Some are anatomical in nature, based on deformed or poorly preserved specimens. Some are based on incorrect collection data or labeling. But this one seems especially dumb — and unfair to the fish in question. Because based on its name alone, even a non-scientist could probably tell you that the Razorback Sucker, Xyrauchen texanus, occurs in Texas. Except that it doesn’t.

The Razorback Sucker was described as Catostomus texanus in 1860 by Charles C. Abbott (1843-1919), an American Civil War surgeon, archaeologist and naturalist. He based his description on a dried specimen at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. This specimen was collected or acquired by entomologist John L. LeConte (1825-1883), responsible for naming and describing approximately half of the insect taxa known in the United States during his lifetime. From 1849 to 1851, LeConte explored California and the Colorado River of Arizona. He apparently acquired the type specimen of X. texanus during this trip. His field notes indicate that the sucker came from the “Colorado and New” rivers. The Colorado River, of course, is a major river of the American Southwest, beginning in Colorado, flowing through Utah and Arizona, then crossing the border into Mexico, where it now runs dry before reaching the Gulf of California. The New River is a tributary of the Gila River, itself a tributary of the Colorado, in central Arizona.

So how did a fish from Arizona get named for the state of Texas? Well, it seems that Abbott mistook the Colorado River of Arizona for a different river of the same name — the Colorado River of Texas, which flows southeast for 1,387 km from Dawson County, through Austin, into the Gulf of Mexico. In addition, some have speculated that Abbott mistook the New River of Arizona for the Nueces River of Texas.

No one seemed to have noticed for nearly 70 years, because Abbott’s description was overlooked by his colleagues. When Eigenmann & Kirsch proposed the genus Xyrauchen (xyron, razor; auchen, nape, referring to its sharp dorsal keel) in 1889, they named it for Quassilabia cypho, described by Lockington in 1879. Even the authoritative Fishes of North and Middle America (1896-1900) failed to notice Abbott’s paper. Henry Weed Fowler, curator of fishes at the museum where LeConte’s dried specimen was housed, was the first to note the oversight, reported by John Otterbein Snyder in 1915. It wasn’t until 1930 when American ichthyologists dropped X. cypho and started using X. texanus instead.

John LeConte lived in Philadelphia. Charles Abbott lived across the Delaware River in nearby New Jersey and no doubt frequented the Academy of Natural Sciences. One can help but wonder if LeConte ever pulled Abbott to the side and said, “Dude, regarding the name of that fish I collected? You got the location wrong.”

Argyrocottus zanderi in Oceanarium of Vladivostok. Photo by A. C. Tatarinov. Courtesy of Wikipedia.

25 July 2018

Argyrocottus zanderi Herzenstein 1892

This is our 250th consecutive weekly “Name of the Week” posting. So here’s an example of the behind-the-scenes work that takes place during our etymological research, whether it’s for the 249 NOTW essays that preceded this one, or the 25,382 entries now online at etyfish.org .

Russian ichthyologist Solomon Markovich Herzenstein (1854-1894) described Argyrocottus zanderi, a new genus and species of North Pacific sculpin, in 1892. The generic name was easy enough to figure out: argryos, silver, and cottus, sculpin, referring to silvery spots on its belly and sides, and two silvery stripes, one from below the eye to the base of the lower jaw, and another from the eye to the preopercle. The specific name zanderi required more effort. An international effort, in fact.

Herzenstein mentioned that he named it for “Dr. Zander,” a medical doctor in St. Petersburg, Russia, who collected the sculpin in 1890 at Sakhalin Island in the Sea of Okhotsk. We were curious: Who, precisely, was this Dr. Zander? And why was he collecting fishes?

We found nothing researching his name in America. So we asked our German friend and colleague Erwin Schraml if he could research Zander’s identity, or at least contact his network of ichthyological colleagues on his side of the Atlantic. Erwin asked Hans-J. Paepke, retired curator of ichthyology at the Berlin Museum of Natural History and a scholar of ichthyological history. Dr. Paepke forwarded our query to Dr. Natalia Chernova, an ichthyologist at the Zoological Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg. So now we had a contact in the very city where Dr. Zander lived and worked.

Dr. Chernova spent a considerable amount of time digging through library and museum archives to compile everything she could find about Zander. His full name was Alexander Karlovich Zander. In 1888, he was hired as a “senior ship doctor” for a trip to Sakhalin Island on the clipper Rider, whose mission was to make topographical images of the coastline. He left Vladivostok on 7 July 1888 and began the voyage home back to St. Petersburg April 1889.

The holotype of A. zanderi was (probably) first entered into the scientific collections of the St. Petrischule in St. Petersburg. Founded in 1709, St. Petrischule specialized in German-language instruction and today still specializes in this subject. The holotype eventually made its way to the Zoological Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences, where Herzenstein examined it. The holotype, number ZIN 9679, has apparently been lost.

Little else is known about Zander. He came from a Prussian family and studied medicine in 1883, but apparently received his medical degree in 1894, after the Sakhalin voyage. His dissertation was on cholera in children and corresponding hygiene problems. In the 1890s he worked at the Nikolaevsky Hospital, where in 1892 a cholera department and a bacteriological laboratory were opened. One of his patients was the composer Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, who died, possibly of cholera (and possibly of suicide), on 25 October 1893.

Zander’s birth and death dates are unknown.

We thank Erwin Schraml, Dr. Hans-J. Paepke, and Dr. Natalia Chernova for helping us learn more about Dr. Zander — who he was, where he worked, and how this sculpin swam into his life.

18 July 2018

Robert C. Cashner (1942-2018)

On 1 July 2018, Dr. Robert C. Cashner, known as “Bob” to his friends, passed away. He was a respected biologist, faculty member, and administrator at the University of New Orleans, where his career spanned 35 years. During that time he authored or co-authored over 60 papers, mostly on freshwater fishes of the American southeast. Although no fishes have been named in his honor (yet), he named or co-named several himself:

Ambloplites constellatus Cashner & Suttkus 1977, a rock bass from Missouri and Arkansas; its name, “with speckles,” refers to the clustered arrangements of dark spots on its sides.

Fundulus euryzonus Suttkus & Cashner 1981, a topminnow from Louisiana and Mississippi, named for the wide (eury) purple-brown stripe (zonus) on its sides.

Campostoma pauciradii Burr & Cashner 1983, a stoneroller minnow from Georgia and Alabama, distinguished from its congeners by having fewer (paucus) gill rakers (radii) on its first gill arch.

Fundulus bifax Cashner & Rogers 1988, a topminnow from Georgia and Alabama; its name, meaning “two-faced,” refers to its strong resemblance to F. catenatus.

Notropis suttkusi Humphries & Cashner 1994, a shiner from Oklahoma and Arkansas, named in honor of Tulane University biologist Royal D. Suttkus (1929-2009), for his “outstanding contributions to North American ichthyologist and cyprinid systematics during a long and productive career.”

Percina brucethompsoni Robison, Cashner, Raley & Near 2014, a logperch from Arkansas, posthumously named in honor of friend and colleague Bruce A. Thompson (1946-2007), an ichthyologist from Louisiana State University, who suspected this logperch was a distinct species in the 1970s.

The Cashners are an ichthyological family. Bob’s wife Frances, who passed away in 2007, was the daughter of legendary ichthyologist Robert Rush Miller (1916-2003). And one of his three daughters, Mollie, is an associate professor at Austin Peay State University (Clarksville, Tennessee), where she studies the evolution of reproductive behavior in fishes.

Bob’s friend and colleague Bill Matthews, a fish ecologist at the University of Oklahoma, offered two insights into the Bob Cashner he knew and loved:

“Bob could be obstinate. He was, I think, pretty proud of his well-groomed Father Christmas beard. On one occasion, he and I were meeting with the suits of a particular oil company to finalize a pretty lucrative contract for us to do fish work for them in deep swamp habitat near a refinery. Near closing of the contract, their safety guy said to Bob, but of course you will have to shave your beard, so a gas mask would fit in an emergency. Bob simply turned to me and said, Let’s go, and we walked out. That would have been that, but the oil folks relented and called us back to sign the contract. Bob kept his beard!”

“Bob was a total humanitarian. When [Hurricane] Katrina wiped out their home, taking with it almost everything he and the family had built up for so many years, his first concern was not for their material things, but for the well-being of three young women from Mali who were enrolled at the University of New Orleans where Bob was Graduate Dean and Associate Chancellor. In spite of his family’s tremendous tangible losses, Bob went to great lengths to personally work with University of Oklahoma admissions to get the women transferred from UNO to OU, and drove them up and stayed to be sure they were established properly and safely in their new school. Three young African women, flooded out and homeless in New Orleans, and Bob made it all possible for them to survive the event. And all three graduated at OU and became highly successful.”

Centropyge eibli, at Menjangan Island, Bali, Indonesia. Source: Sally Polack / FishWise Professional.

11 July 2018

Irenäus Eibl-Eibesfeldt (1928-2018)

He was co-founder of the field of human ethology. But amidst his groundbreaking work on the study of human behavior, Dr. Irenäus Eibl-Eibesfeldt also dabbled in ichthyology. He passed away last month, 2 June, two weeks shy of his 90th birthday.

Born in Vienna, Eibl-Eibesfeldt was given the (even back then) unusual name of Irenäus. Nicknamed Renki, he spent more in the outdoors observing animals than going to school. In 1946, he began studying zoology at the University of Vienna in 1946. There he met famed animal ethologist Konrad Lorenz (1903-1989), and later earned his doctorate under Lorenz studying the social behavior of squirrels.

In the 1950s, Eibl-Eibesfeldt met Hans Hass (1919-2013), a “celebrity” marine biologist and a pioneer in scuba diving (see NOTW for 21 February 2018), and his ichthyologist dive partner, Wolfgang Klausewitz (b. 1922). Together they went on a long expedition to the Indian Ocean, known as the Xarifa Expedition, named for Hass’ research schooner. The primary objective of the expedition was to use to the “new Scuba equipment” as well as custom-made underwater cameras and television gear for obtaining scientific data about coral reefs.

Eibl-Eibesfeldt collected (or helped collect) several new species, three of which he co-described: the jawfish Opistognathus annulatus (Eibl-Eibesfeldt & Klausewitz 1961), and two garden eels: Gorgasia maculata Klausewitz & Eibl-Eibesfeldt 1959 and Heteroconger hassi (Klausewitz & Eibl-Eibesfeldt 1959). Eibl-Eibesfeldt’s study of H. hassi incorporated the first (or one of the first) uses of remote cinematography to study marine life. Hass and team placed their cameras on the reef or sea floor at depths of up to 100 m, while Eibl-Eibesfeldt watched the garden eels from on board ship, sometimes at night.

Eibl-Eibesfeldt described another garden eel — Heteroconger klausewitzi (Eibl-Eibesfeldt & Köster 1983) — from the Galápagos in 1983. In addition, he studied the symbiotic cleaning behavior between shrimps and fished and the tournament battles of marine iguanas.

In the 1960s, Eibl-Eibesfeldt turned his research focus to humans, studying them as he would any other animal. One of his most famous studies was the documentation of the non-verbal behavior of blind and deaf-born children, which showed that emotional facial expressions are innate among humans. Eibl-Eibesfeldt quickly realized that the behavior of people in very different parts had the same non-verbal grammar (e.g., showing anger, grief, surprise, embarrassment, joy and eye greetings).

In 1963, a beautiful marine angelfish, Centropyge eibli, now popular among aquarists, was named after him. Eibl-Eibesfeldt had collected the three type specimens during the final leg of the Xarifa Expedition.

Redbreast Sunfish, Lepomis auritus. Photo by Scott Smith. Courtesy: North American Native Fishes Association.

4 July 2018

America’s first fish: Lepomis auritus (Linnaeus 1758)

Today is Independence Day, a federal holiday in the USA commemorating the ratification of the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776. On this day, the Continental Congress officially announced that the 13 colonies of America were no longer part of the British Empire but represented a new nation, the United States of America. (Actually, Congress voted to declare independence two days earlier, on July 2.) This got us to wondering:

What was the first inland fish from the United States to be described?

The answer is the Redbreast Sunfish, which Linnaeus described as Labrus auritus in the 10th edition of his Systema Naturae, the first official work of zoological nomenclature. “Auritus” means “eared” and refers to the long opercular flap of adults. Linnaeus also described the Pumpkinseed Sunfish, Perca gibbosa (now Lepomis gibbosus) in the same publication, but since it appeared nine pages later, we consider it America’s “second fish.”

Labrus auritus officially settled in the genus Lepomis in 1883. Proposed by Rafinesque in 1819, Lepomis translates as lepis, scale and poma, lid, once again referring to the opercular flap that’s a characteristic of adults of the genus. Rafinesque used the flap to distinguish sunfishes from the bream genus Sparus (Sparidae), thought to be related at the time.

The Declaration of Independence was signed and ratified in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The specimen that Linnaeus used to describe “America’s first fish” hailed from Philadelphia too!

Sandelia bainsii. From Boulenger, G. A. 1916. Catalogue of the fresh-water fishes of Africa in the British Museum (Natural History). London. v. 4: i-xxvii + 1-392.

27 June 2018

Sandelia bainsii Castelnau 1861

This name is curious in that its two halves honor individuals who were on opposing sides of the tense, violent struggles of 19th-century colonial South Africa.

The Eastern Cape Rocky, Sandelia bainsii, is a critically endangered anabantid fish endemic to freshwater rivers of the Eastern Cape of South Africa. Francis Castelnau proposed the genus and the species in the same publication. He said that the species name is dedicated to the “savant géologue M. Bains.” The “M.” is for “Monsieur.” The spelling “Bains” appears to be incorrect. Unless there was another South African geologist who went my that name, Castelnau was almost certainly honoring Andrew Geddes Bain (1797-1864), a Scottish-born South African geologist, palaeontologist, road engineer, and explorer.

Bain emigrated to Cape Town in 1816. He explored northern South Africa, collecting zoological specimens and publishing articles about his journeys, accompanied by his own illustrations. He used his knowledge of geology to survey land for potential road-building projects for the South African Corps of Royal Engineers. This led to permanent employment as a road engineer, builder and inspector. In addition, he served as a captain in the Cape Frontier Wars, a series of nine wars or skirmishes (1779-1879) between the Xhosa tribes and European settlers along South Africa’s Eastern Cape.

As an active participant in the Cape Frontier Wars, Bain had no doubt heard of Mgolombane Sandile. Born in 1820, Sandile was a Chief of the Ngqika tribe and a Paramount-Chief of the Rharhabe tribe, a sub-group of the Xhosa nation. Sandile led the Ngqika people in the Seventh Frontier War (1846-47), Eighth Frontier War (1850-53) and the Ninth Frontier War (1877-78), in which he was killed. These clashes marked the beginning of the use of firearms by Xhosa armies, scoring many victories for Sandile, earning him a reputation as a Xhosa hero and mighty warrior.

Castelnau named the genus in honor of Sandile (which he spelled Sandelie). It is not clear whether he intentionally meant to honor both sides of the conflict in the same name. Nor is it known what Bain thought of having his name so closely associated with Sandile’s.

Painting by Peter Paul Rubens of Cronus devouring one of his children.

20 June 2018

Haplochromis cronus Greenwood 1959

Infanticide and paedophagia. These are the virtues celebrated in the specific name of this “happie” from Lake Victoria. Cichlid taxonomist Peter Humphry Greenwood (1927-1995) of the British Museum did not provide an etymology in his description. But he dropped enough clues for us to figure it out.

Back in the Golden Age of Greek mythology, Cronus (sometimes spelled Cronos or Kronos) was the leader and youngest of the first generation of Titans. He envied the power of his father, Uranus, the ruler of the universe. So Cronus castrated his dad with a sickle and threw his testicles into the sea. Understandably angry, Uranus convinced Cronus that his own children were destined to overthrow their father just as Cronus had overthrown his. To prevent this prophecy, Cronus devoured his first five children — Demeter, Hestia, Hera, Hades and Poseidon — as soon as they were born. Kid #6, Zeus, was born and raised in secrecy. In one version of the story, a grown-up Zeus freed his siblings by giving his father an emetic, forcing Cronus to literally vomit his kids to freedom. In another version, Zeus simply cut his father’s stomach open. With the help of his liberated brothers and sisters, Zeus overthrew his father and the Titans, becoming the king of the gods of Mount Olympus.

Greenwood must have chuckled when he coined the name. As revealed by the stomach contents of the type specimens, this “happie” feeds almost exclusively on the embryos and larvae of cichlids, especially other Haplochromis species.

13 June 2018

13 June 2018

In honor of Conrad Limbaugh (1925-1960)

Five fishes are posthumously named in honor of Conrad (“Connie”) Limbaugh. Many more fishes would likely bear his name had he not died while diving in an underground river in France.

Born in 1925, Limbaugh grew up in Laguna Beach, California. He started skin diving as a teenager, using a coffee can and piece of glass as his mask. He loved spearfishing and learned to identify the fishes and invertebrates he observed. Upon completing his undergraduate degree in biology in 1949, he joined the graduate zoology program at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). That’s when he learned of Jacques Cousteau’s new invention, the Aqua-lung. Conrad convinced his advisors to purchase an Aqua-lung for underwater observations and experiments. He eventually transferred to the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, studying under the legendary ichthyologist Carl Hubbs.

At Scripps, Limbaugh spent countless hours in the ocean, observing the behavior of fishes and invertebrates, tagging fishes, and collecting specimens. He taught himself underwater photography and later worked as a freelance cinematographer for underwater nature documentaries produced by Walt Disney. Limbaugh also became a pioneer in scuba training and safety, working with fellow grad student Andreas Rechnitzer to develop America’s first civilian diving course. They felt more comfortable diving together, which lead them to develop the “buddy system,” the safety procedure that divers all over the world depend on today.

After his dives, Limbaugh spent hours typing up detailed accounts of what he observed. He turned these accounts into articles for popular magazines, and peer-reviewed papers for academic journals. His most significant scientific contribution was his work on symbiotic cleaning behavior between fishes and shrimps.

In 1960, Jacques Cousteau invited Limbaugh to attend the first meeting of the Confédération Mondiale des Acitivités Subaquatiques (CMAS), in Barcelona, Spain. Attendees at the meeting told Limbaugh of an underground river at Port Miou, 32 km from Marseille, France. At this location, saltwater fishes from the Mediterranean were said to rid themselves of parasites by swimming into the fresh water of the underground river, quivering for a moment, then dropping back into the sea. Limbaugh borrowed diving gear and accompanied two French divers to the location. One stayed on the boat, the other served as his dive buddy and guide.

Inside the underground river, Limbaugh and his guide swam 45 m to where a chimney, open to the land above, had sent eroding rocks to form a cone on the river’s floor below. Always the cinematographer, Limbaugh insisted on getting a shot up the chimney with his 16 mm movie camera. To help him, his dive buddy placed his flashlight on the cone of rocks below and gave Limbaugh a boost. Limbaugh got the shot. The dive buddy descended to retrieve the flashlight, but when he returned Limbaugh was gone. His body was found one week later some 100 m from the entrance of the cave. No one knows what happened.

After Limbaugh’s death, his brother-in-law spent several years bringing Limbaugh’s unpublished manuscripts and notes to publication, including his most famous paper, “Cleaning Symbiosis,” which appeared in a 1961 issue of Scientific American. Today, Limbaugh’s fame lives on in the names of five fishes:

Holacanthus limbaughi Baldwin 1963, a marine angelfish, which Limbaugh helped collect during an expedition he led to Clipperton Island, an uninhabited coral atoll in the eastern Pacific off the coast of Central America

Chaenopsis limbaughi Robins & Randall 1965, a pikeblenny from the Virgin Islands, for Limbaugh’s detailed field observations of a related species, C. alepidota

Chromis limbaughi Greenfield & Woods 1980, a damselfish from the Gulf of California, which Limbaugh collected and photographed in 1954

Tigrigobius limbaughi (Hoese & Reader 2001), a goby from the Gulf of California, for Limbaugh’s “pioneering” 1961 work on the symbiotic cleaning behavior of marine organisms [oddly, the authors give Limbaugh’s forename as “Clyde”]

Icelinus limbaughi Rosenblatt & Smith 2004, a sculpin from La Jolla Submarine Canyon, California, for collecting type in 1955, and for his pioneering work as diving officer at Scripps, which “paved the way for the modern techniques of collection, manipulation, and observation of underwater marine life for scientific study”

In addition to countless admirers in diving and marine biology, Limbaugh had one admirer in literature as well. In 1961, the English-American poet W. H. Auden wrote: “If I ask myself what single piece of literature gave me greatest pleasure in 1961, it was [Limbaugh’s] article in the ‘Scientific American’ called ‘Cleaning Shrimps [sic].’ Perhaps I should explain that it’s concerned not with preparing shrimps for the table but with shrimps who live from cleaning fish.”

Toxotes chatareus (young). Photo by Bounthob Praxaysombath. Courtesy of Fishes of Mainland Southeast Asia .

6 June 2018

Toxotes chatareus (Hamilton 1822)