NAMES OF THE WEEK from: 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 2023 2025

25 December

Fishes from the Holy Land

Today is Christmas, the annual festival commemorating the birth of Jesus. Several fishes from the area where Jesus was born, preached and died are named for either their association with Jesus, or to the Holy Land area in general.

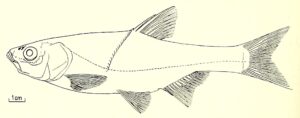

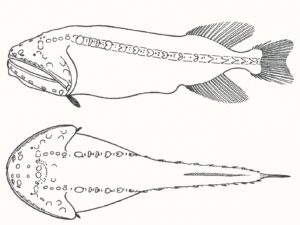

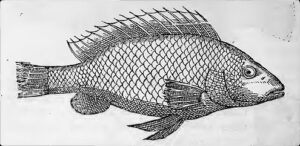

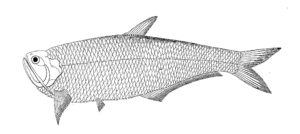

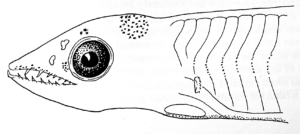

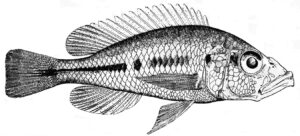

Possibly first-published full-body image of body of Mirogrex terraesanctae (original description illustrated only the pharyngeal teeth). From: Goren, M., L. Fishelson and E. Trewavas. 1973. The cyprinid fishes of Acanthobrama Heckel and related genera. Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History) Zoology 24 (6): 293–315.

Mirogrex terraesanctae is a planktivorous minnow (Leuciscidae) known from Lake Tiberias (also known as the Sea of Galilee and Lake Kinneret) in Israel and Lake Muzayrib in Syria. Described as Acanthobramus terrasanctae in 1952, the specific name means “of the Holy Land,” from the Latin words terra, land, and sanctus, holy. In 1973, a new genus was proposed for the species: Mirogrex Goren, Fishelson & Trewavas 1973, from the Latin mirus (L.), wonderful or amazing, and grex, Latin for flock or shoal. The name refers to the “miraculous draught” of fishes (one of two miracles attributed to Jesus), which may have been M. terraesanctae or Sarotherodon galilaeus (Cichlidae).

Another species named for the Latin word for sacred is the cichlid Tristramella sacra (Günther 1865). Like Mirogrex terraesanctae, it was described from Lake Tiberias but has not been recorded from there since 1990, probably due to decreasing water levels that destroyed the marshy areas where it spawned. Although the cichlid is officially treated as extinct by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), there are reports that it still survives in Syria.

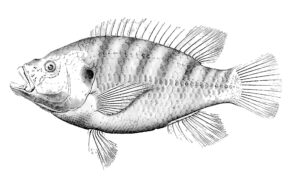

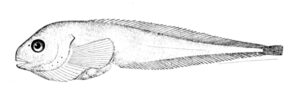

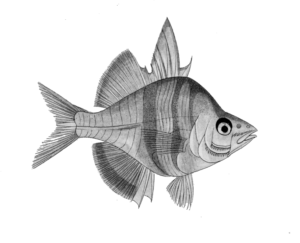

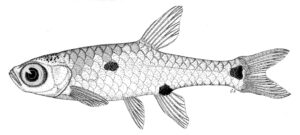

Tristramella magdalenae. Lortet, L. 1883. Études zoologiques sur la faune du lac de Tibériade, suivies d’un aperçu sur la faune des lacs d’Antioche et de Homs. I. Poissons et reptiles du lac de Tibériade et de quelques autres parties de la Syrie. Archives du Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle de Lyon 3: 99–189, Pls. 6–18.

Tristramella magdalenae Lortet 1883 was described from lakes Hula and Tiberias (Sea of Galilee) in Israel, and from swamps and pools in the Damascus area of Syria. It apparently is extirpated in Israel but survives in Syria. Lortet did not explain the meaning of the name. Here are two guesses: The name refers to Mary Magdalene (or Mary of Magdala), a disciple of Jesus Christ who, according to gospel, witnessed his crucifixion and resurrection. Or the name refers to Magdala, a village on the shore of Lake Tiberias.

Tristramella simonis (Günther 1864) is another cichlid from Lake Tiberias. Günther did not explain the name but our guess is that it’s the genitive singular of Simon, original name of Saint Peter, one of the Twelve Apostles of Jesus, possibly referring to “St. Peter’s Fish,” a Biblical story in which Peter caught a fish from the Sea of Galilee that carried a coin in its mouth. Although the biblical passage does not name the fish, many believe it was Saratherodon galilaeus, whereas others suggest it was this species, which, as a mouthbrooder, has a mouth large enough to accommodate a coin.

18 December

Lotella rhacina (Forster 1801)

Lotella rhacina in Jervis Bay, New South Wales, 2 April 2016. Source: John Turnbull / Flickr. From: https://fishesofaustralia.net.au

Many fishes, especially those from the Mediterranean, have names that date to ancient Greece and Rome. But the meanings of such names, and even the species they refer to, often change or get lost entirely over the centuries. Monks working in scriptoria can miscopy the texts they are copying by hand on parchment. Translators may mistranslate or change the meaning of a text. And translators who translate the translations can compound these errors even more. By the time an ancient name reaches an 18th– or 19th-century naturalist who formally assigns the name to a species, the original meaning of the name may be long gone. Imagine a lexicological version of the children’s game (called “telephone” in the US and Canada) in which players whisper a message to each other in a circle or line, and the message often becomes distorted by the time it reaches the last player.

The specific name of the Rock Cod Lotella rhacina is a case in point. No one knows what the specific epithet means, mainly because it’s not a Greek or Latin word. Originally, The ETYFish Project reported that “rhacina” is from “rhacinus,” the ancient name for a small black fish, dating to “Halieutica” (“On Fishing”), a fragmentary didactic poem spuriously attributed to Ovid, circa AD 17. Thanks to our friend and contributor Holger Funk, we now know that the full story of the name. It’s quite convoluted, so bear with us.

According to Dr. Funk, the first printed edition of “Halieutica” was published in Venice in 1534. It contains this passage: “caeruleaque rubens erythinus in unda” (“and the erythinus glowing red in the blue wave”). Erythinus (or Erythrinus) is an unidentified deep-sea fish, probably a grouper or sea bass (Serranidae) or a porgy (Sparidae). The name is derived from ἐρυθρός, meaning red. No one questions this reading. In fact, it appears in the most recent critical edition of “Halieutica” published by the Loeb Classical Library in 1929 along with several reprints since then.

But that’s not the reading that apparently made its way to Johann Reinhold Forster (1729–1798), the naturalist aboard the second voyage of Capt. James Cook around the world. Forster encountered a new kind of fish captured off Queen Charlotte Sound in New Zealand. He named it “Gadum Rhacinum” in an unpublished manuscript. German naturalist Johann Schneider (1750–1822) quoted a portion of Forster’s manuscript in his 1801 edition of Bloch’s Systema Ichthyologiae, crediting Forster with the name and emending it to Gadus rhacinus. In 1844, Forster’s complete manuscript was posthumously published. Forster was quite clear about why he selected the name: “Since Ovid called a certain fish of a dusky or black color Rhacinus, and our Gadus is of exactly the same color, I did not hesitate to call the same Rhacinus” (translated from Latin).

But wait! The fish in “Halieutica” is “glowing red,” not black. And where did the word “Rhacinus,” not mentioned in “Halieutica,” come from? Here’s where the convolutions begin.

Forster apparently was not citing “Halieutica” directly, but rather passages from “Halieutica” quoted by Roman author and naturalist Pliny the Elder in his encyclopedic Naturalis Historia (AD 77–79). In a 1476 printed edition of Pliny’s work, the uncontested passage “caeruleaque rubens erythinus in unda” is corrupted as “nubentemque acrium pulum.” This is nonsensical Latin, according to Dr. Funk, untranslatable, even if one corrects the obvious misspellings “nubentemque” and “pulum” to reasonable Latin wording (“rubentemque” and “pullum”). Italian anatomist and surgeon Alessandro Benedetti (ca. 1450–1512) apparently tried to fix this reading in his edition of Pliny’s work, published in 1513: “rhacinumque pullum” (“and the black rhacinus”). The same error (“the blacke Rhacinus”) is found in 1634 English translation of Pliny’s work by Philemon Holland (1552–1637).

To review: caeruleaque rubens erythinus in unda” (“and the erythinus glowing red in the blue wave”) somehow became “rhacinumque pullum” (“and the black rhacinus”).

Our guess is that Forster had read Benedetti’s edition of Pliny, or Holland’s translation, or perhaps some other edition that repeated the “black Rhacinus” mistake. Forster repurposed or resurrected the ancient name for a similarly black or blackish fish. The fact that Lotella rhacina is actually yellow-grey to red-brown in life is not important; it’s possible that Forster’s specimen turned darker after death or in spirits.

Dr. Funk called “rhacinus” an “un-word.” You won’t find it in any classical Greek or Latin dictionary. And despite the fact that classical scholars were aware that “rhacinus” is a mistake, it lives on, rather nonsensically, in the name of a fish.

11 December

Eight new species of Parauchenoglanis

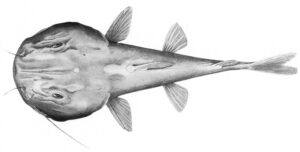

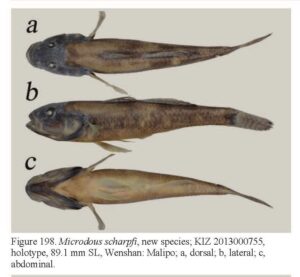

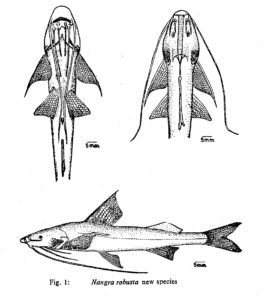

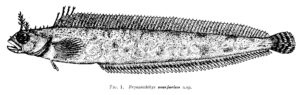

Top: Parauchenoglanis dolichorhinus. Middle: Parauchenoglanis poikilos. Bottom: Parauchenoglanis megalasma. From: Dr. Sithole’s essay.

While most ichthyologists who describe new taxa probably give careful consideration to the names they choose, it’s rare when one acknowledges the value of a name. Here’s a refreshing exception.

Last month, a team of five ichthyologists published a paper revealing hidden species diversity in the widespread Zambezi Grunter Parauchenoglanis ngamensis, a catfish from southern and south-central Africa. Using a combination of molecular (barcoding), color pattern, and other morphological data, the authors discovered that P. ngamensis actually represents nine species, eight of them new. In addition to the formally published descriptions, the study’s lead author, Yonela Sithole of the South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity (SAIAB), also wrote a public-outreach essay for SAIAB’s website. In the essay, titled “Unveiling New Species: How Eight New Catfish Species Were Named,” Dr. Sithole writes:

“Naming a new species is a significant aspect of scientific research, and each name carries meaning, whether it reflects a key feature of the species, its place of discovery, or honours a person who has contributed to the field.”

I can’t think of a more succinct explanation of the value of the names we celebrate at The ETYFish Project.

Here are the names of the eight new species and what they mean:

Species named after people:

Parauchenoglanis patersoni in honor of Angus Paterson, former managing director of the National Research Foundation-South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity (NRF-SAIAB), for his “determination and efforts to build taxonomic expertise and drive ichthyological exploration in poorly surveyed areas in southern Africa”

Parauchenoglanis ernstswartzi in honor of Ernst Swartz, Research Associate, South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity, who collected specimens used in the description of six new species in the authors’ study, for his “pioneering and extensive exploration of the Kwanza and adjacent river systems, including the upper Kasai sub-basin”

Species name based on external characteristics:

Parauchenoglanis dolichorhinus from the Greek dolichós (δολιχός), long, and rhinós (ῥινός), genitive of rhís (ῥίς), nose, referring to its long snout (preorbital length) compared with others in the P. ngamensis group

Parauchenoglanis poikilos from the Greek adjective poikílos (ποικίλος), spotted, referring to the numerous distinctive spots along its body

Parauchenoglanis megalasma from the Greek mégas (μέγας), large or great, and mélasma (μέλασμα), black spot, referring to the prominent, large black blotches along its lateral line

Species named after locations:

Parauchenoglanis lueleensis –ensis, Latin suffix denoting place: Luele River in the Kasai sub-basin, Angola, where it occurs

Parauchenoglanis luendaensis –ensis, Latin suffix denoting place: Luenda River in the Kasai sub-basin, Angola, where it occurs

Parauchenoglanis chiumbeensis –ensis, Latin suffix denoting place: Chiumbe River in the Kasai sub-basin, Angola, type locality

The name of the genus Parauchenoglanis, proposed by Belgian-born British ichthyologist-herpetologist George A. Boulenger (1858–1937) in 1911, begins with the Greek prefix pará (παρά), meaning near, referring to the genus’ similarity to and/or close relationship with Auchenoglanis, the type genus of the catfish family Auchenoglanididae. Boulenger also described the Zambezi Grunter Parauchenoglanis ngamensis, naming it for the Lake Ngami district (of area) of Botswana, where it was first collected.

Dr. Sithole concludes here essay saying, “The diversity of names reflects the rich variety of physical characteristics and habitats of these fish, as well as the importance of ichthyological exploration in Africa. By honouring people, places, and unique features, the naming process adds a layer of meaning to the scientific discovery, ensuring that these species are forever linked to the stories of their discovery.”

4 December

4 December

G. David Johnson (1945–2024)

Four days after the passing of David G. Smith (see last week’s NOTW), the Smithsonian Institution’s Division of Fishes lost another prominent colleague, G. David Johnson. He died after a fall following cardiac arrest.

Dr. Johnson earned his BS from the University of Texas, Austin, and his PhD from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography. He joined the curatorial staff of the Smithsonian’s Division of Fishes in 1983. His areas of specialty were the comparative morphology of fishes in general and the taxonomy of larval fishes in particular. Dr. Johnson’s name is attached to 11 new genera and 40 new species of fishes from 1977 to 2013, usually in collaboration with some of the best-known ichthyologists of the day, including William F. Smith-Vaniz, Richard H. Rosenblatt, Carole C. Baldwin, William D. Anderson, Jr., John R. Paxton, Stuart G. Poss, Hsuan-Ching Ho, Keiichi Matsuura, Seishi Kimura, Matthew G. Girard, and the aforementioned David G. Smith.

Three of Dr. Johnson’s many publications stand out in my memory.

- The 2009 discovery that fishes assigned to three families with greatly differing morphologies, Mirapinnidae (tapetails), Megalomycteridae (bignose fishes) and Cetomimidae (whalefishes), are larvae, males and females, respectively, of a single family, Cetomimidae.

- The description of a new family, genus and species of eel, Protanguilla palau, from a deep underwater cave in a fringing reef off the coast of Palau. This eel is considered to be the most primitive living lineage of anguilliform fishes.

- The description of Monomitopus ainonaka Girard, Carter & Johnson 2023, which highlights the “importance of blackwater photography in advancing our understanding of marine larval fish biology.” (See NOTW 20 Sept. 2023.) The species is name for Dr. Johnson’s wife, Ai Nonaka, a research assistant at the Smithsonian’s Division of Fishes.

For his scholarly contributions, Dr. Johnson received the Robert H. Gibbs, Jr. Memorial Award for Excellence in Systematic Ichthyology by the American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists in 2003.

Only one species of fish so far has been named in Dr. Johnson’s honor. It is the White-cheeked Blenny Acanthemblemaria johnsoni Almany & Baldwin 1996, found in coral reefs around Tobago in the western central Atlantic Ocean. Dr. Johnson collected the holotype and was honored for his contributions to the systematics of a broad array of teleostean taxa (including Acanthemblemaria), and his “inspirational” knowledge of teleostean anatomy and phylogeny.

Those who followed Dr. Johnson on social media know that his avatar was a “mug shot” he took of a museum specimen of the deep-sea Telescope Fish Gigantura indica. The photo has become an online celebrity of sorts, being widely shared, “memed” and commented upon. My son, when he was in middle school, encountered the photo online and painted a water-color version of it in art class. The painting now hangs in our family room. A few weeks ago, a good friend of ours visited with her high-school-aged son. He saw the painting and said, “Hey, look, a Telescope Fish.”

I like to think that Dr. Johnson would have appreciated that.

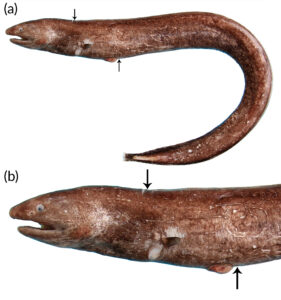

Gymnothorax smithi, paratype, 362 mm TL. From: Sumod, K. S., A. Mohapatra, V. N. Sanjeevan, T. G. Kishor and K. K. Bineesh. 2019. A new species of white-spotted moray eel, Gymnothorax smithi (Muraenidae: Muraeninae) from deep waters of Arabian Sea, India. Zootaxa 4652 (2): 359–366.

27 November

David G. Smith (1942–2024)

Last week was an extraordinarily sad week at the Smithsonian Institution’s Division of Fishes. Two of their ichthyologists have passed away, David G. Smith on November 18, and G. David Johnson on November 22. We’ll honor their contributions this week and next, starting with Dr. Smith.

David G. Smith was the world’s taxonomic authority on eels (Anguilliformes), and served as our go-to expert whenever we needed help with an “eel-tymology.” He described or co-described one new family (Colocongridae), eight new genera and 74 new species, all of which remain valid today. Perhaps his greatest systematic contribution was preparing original content and editing the two volumes (Volume 1, adult eels, Volume 2, Leptocephali) of Part Nine of the Fishes of the Western North Atlantic series, published in 1989. In addition to naming many eel taxa, six fish species, four of them eels, have been named after him:

Gymnothorax davidsmithi McCosker & Randall 2008 … Flores Mud Moray from Indonesia

Gymnothorax smithi Sumod, Mohapatra, Sanjeevan, Kishor & Bineesh 2019 … Indian White-spotted Moray from the western Indian Ocean

Gnathophis smithi Karmovskaya 1990 … a conger eel from the southeast Pacific

Rhynchoconger smithi Mohapatra, Ho, Acharya, Ray & Mishra 2022 … a longnose conger eel from the eastern Indian Ocean

Elops smithi McBride, Rocha, Ruiz-Carus & Bowen 2010 … Southern Ladyfish (Elopidae) from the western South Atlantic

Ogilbia davidsmithi Møller, Schwarzhans & Nielsen 2005 … Cortez Brotula (Dinematichthyidae) from the Gulf of California

Dr. Smith was born in Buffalo, New York, and was awarded his BS in Vertebrate Zoology at Cornell University (1964), and his MS and PhD from University of Miami (1967, 1971, respectively). Dr. Smith was a Museum Specialist in Smithsonian’s Division of Fishes from 1989 until his retirement in 2012. He inventoried their collection of Anguilliformes, including cataloging 8,600 (25,320 specimens) of the 13,900 total eel lots (40,500 specimens). In so doing, he reidentified nearly all of the museum’s holdings of eels, the largest collection of eels in the world. In addition to his research on eels, Dr. Smith was also the Ichthyology Historian for the American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists (ASIH). Often in collaboration with his wife, Inci Bowman, he wrote in-depth essays on the lives of members of ASIH published in the Society’s journal. The ETYFish Project has made frequent use of these superb essays.

Dr. Smith’s scholarly contributions were celebrated by ASIH earlier this year when he received the Society’s Robert H. Gibbs, Jr. Memorial Award for Excellence in Systematic Ichthyology. His Smithsonian colleague, Dr. Katherine E. Bemis, nominated him for the award (read her nomination letter here). In his brief acceptance speech, recorded just five months before his passing, Dr. Smith described himself, quoting baseball great Lou Gehrig, as the “luckiest man on the face of the Earth.”

SPECIAL THANKS to Dr. Katherine E. Bemis, NOAA Fisheries National Systematics Laboratory, for sharing the video and her letter nominating Dr. Smith for the Gibbs Award.

Coryphaena equiselis. Courtesy: The Fishes of North Carolina

20 November

Coryphaena equiselis Linnaeus 1758

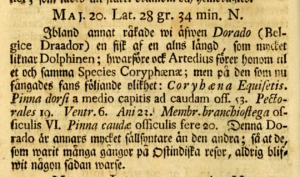

Thanks to ETYFish contributor Holger Funk, we now have a more accurate understanding of the etymology of “equiselis” in the name of the Pompano Dolphinfish Coryphaena equiselis.

Originally, we had posted:

pre-Linnaean name coined as equisetis by Osbeck (1757), equus, horse; setis, bristle, allusion not explained, possibly referring to mane-like dorsal fin (Linnaeus changed spelling to equiselis when he made name available; since Linnaeus continued to use that spelling in future works, his spelling is retained)

Two errors: (1) Swedish naturalist Pehr Osbeck (1723–1805) did not “coin” the name. (2) Linnaeus did not change the spelling of “equisetis” to “equiselis.” Someone else did. Here’s the full story:

“Equiselis” is a corrupted spelling of the plant name “equisaetum” from Pliny’s Natural History and usually identified as the vascular plant Horsetail Equisetum arvense, described by Pliny as being “covered with horsehair” (equus = horse; seta or saeta = hair or bristle). Theodorus Gaza (1400–1475), a Greek humanist and translator of Aristotle, published the name as “equiselis” in his translation of Aristotle to render the fish name híppouros (ἵππουρος) from Pliny. (See footnote, below.) The change from “equisetis” to the nonsensical “equiselis” was probably a scribe’s error.

Pehr Osbeck corrected Gaza’s spelling from “equiselis” to “equisetis” in his 1757 work Diary of an East Indian journey in 1750, 1751, 1752: With notes on natural science, on the language, customs, housework, etc. of various peoples (detail shown here.) Linnaeus was no doubt familiar with Osbeck’s work. After all, Osbeck was one of Linnaeus’ “apostles,” a group of students who collected plant and animal specimens for their teacher throughout the world. But Linnaeus retained the misspelling because that was the spelling used by his friend Peter Artedi (1705–1735), the so-called “father of modern ichthyology.” Linnaeus drew upon Artedi’s posthumously published Ichthyologia sive opera omnia piscibus (1738) for the fish portions of his tenth edition of Systema naturae (1758) — the starting point of zoological nomenclature — and where the name Coryphaena equiselis made its official debut.

Pehr Osbeck corrected Gaza’s spelling from “equiselis” to “equisetis” in his 1757 work Diary of an East Indian journey in 1750, 1751, 1752: With notes on natural science, on the language, customs, housework, etc. of various peoples (detail shown here.) Linnaeus was no doubt familiar with Osbeck’s work. After all, Osbeck was one of Linnaeus’ “apostles,” a group of students who collected plant and animal specimens for their teacher throughout the world. But Linnaeus retained the misspelling because that was the spelling used by his friend Peter Artedi (1705–1735), the so-called “father of modern ichthyology.” Linnaeus drew upon Artedi’s posthumously published Ichthyologia sive opera omnia piscibus (1738) for the fish portions of his tenth edition of Systema naturae (1758) — the starting point of zoological nomenclature — and where the name Coryphaena equiselis made its official debut.

While neither Gaza, Osbeck, Artedi nor Linnaeus explained why the fish’s name means “horse hair,” the best guess is that it refers to the mane-like dorsal fin.

Footnote: Pliny’s híppouros is the source of Coryphaena hippurus Linnaeus 1758, the Dolphinfish (or Mahi-mahi in the restaurant trade). The name translates as “horsetail,” which has confused scholars for centuries since the fish’s forked tail looks nothing like that of a horse. It’s interesting to note that the names of both C. equiselis and C. hippurus mirror the names of two superficially similar genera of plants, Horsetail (Equisetum) and Mare’s-tail (Hippurus). The stalks of both plants, with their bristly branches, have some resemblance to a horse’s tail. For reasons perhaps known only to the ancients, names for the horsetail-like plants were applied to the fish’s mane-like dorsal fins.

13 November

13 November

The “Dune” pipefish

“The Lord of the Rings” has inspired several fish names. “Star Wars” and “Dr. Who” have inspired a few as well. Now we have another sci-fi/fantasy-themed entry in piscine nomina, a new species of freshwater pipefish named for Arrakis, the desert planet in Frank Herbert’s 1965 novel Dune and subsequent sequels and film adaptations.

Lophocampus (originally Microphis) arrakisae, paratype, female, 93.86 mm SL, and holotype, male, 107.93 mm SL. Photo by Nicolas Hubert. From: Haÿ, V., M. I. Menneson, H. Dahruddin, S. Sauri, G. Limmon, D. Wowor, N. Hubert, P. Keith and C. Lord. 2024. A new freshwater pipefish species (Syngnathidae: Microphis) from the Sunda shelf islands, Indonesia. Zootaxa 5536 (1): 139–152.

Microphis arrakisae, with a long list of authors — Haÿ, Mennesson, Dahruddin, Sauri, Limmon, Wowor, Hubert, Keith & Lord 2024 — does not occur in a desert. Instead, it occurs in freshwater streams in the western Indonesia islands of the Sunda Shelf, including Java, Bali and Lombok. So why the reference to a sand- and rock-covered fictional desert planet inhabited by giant sandworms known as “Shai-Hulud”?

Three reasons: (1) The name is a “tribute” to Herbert’s to “influential” work of science fiction. (2) The fish’s yellowish coloration in life resembles the color of sand. (3) The fish’s swimming behavior between rocks is like that of a snake or a worm, and reminiscent of the planet’s giant sandworms and reflects the etymology of the generic name Microphis (from the Greek mikrós, small, and óphis, serpent).

6 November

Snubbed again!

Once again, The ETYFish Project has failed to win the Nobel Prize for Ichthyology.

Because, once again, the Nobel Prize Foundation has refused to recognize ichthyology as a category worthy of its award.

Why Stockholm continues to snub ichthyology in favor of medicine, literature, physics, chemistry, economics and peace is beyond us.

But we’re not bitter. In fact, we’d like to take this opportunity to recognize the many Nobel Prize laureates honored in the names of fishes.

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

Abudefduf lorenzi. Photo by John E. Randall. Courtesy: FishBase.

Abudefduf lorenzi Hensley & Allen 1977 — a damselfish from the western Pacific Ocean named for Austrian zoologist Konrad Lorenz (1903–1989), for his contributions to the science of ethology. Lorenz shared the Nobel Prize in 1973 with Karl von Frisch and Nikolaas Tinbergen for their discoveries concerning organization and elicitation of individual and social behavior patterns

The Nobel Prize in Literature

Etheostoma faulkneri Sterling & Warren 2020 — in honor of writer William C. Faulkner (1897–1962), a native of Oxford, Mississippi (USA); an avid hunter and fisher, the landscape was an important theme in many of his works, and the actions of his characters were often influenced by the lands and streams surrounding his fictional Jefferson, Mississippi, including the Yocona River, where this darter occurs. Faulkner won the Nobel Prize in 1949 for his “powerful and artistically unique contribution to the modern American novel”

Lampanyctus steinbecki Bolin 1939 — a lanternfish (Myctophidae) named in honor of Bolin’s friend John Steinbeck (1902–1968), author of such classic American novels as Of Mice and Men and The Grapes of Wrath, and a serious amateur naturalist who enjoyed collecting and studying the aquatic life of Monterey Bay and the Gulf of California. Steinbeck won the Nobel Prize in 1962 for his “realistic and imaginative writings, combining as they do sympathetic humour and keen social perception”

Trichomycterus garciamarquezi Ardila Rodríguez 2016 — named in honor of writer Gabriel Garcia Marquez (1927–2014), who was born in the area of Colombia bordered by the rivers Tucurinca and Aracataca, where this catfish occurs. Garcia Marquez won the Nobel Prize in 1982 for his “novels and short stories, in which the fantastic and the realistic are combined in a richly composed world of imagination, reflecting a continent’s life and conflicts”

The Nobel Peace Prize

Nansenia Jordan & Evermann 1896 — pencil smelt genus (Microstomatidae) named for the authors’ friend Fridtjof Nansen (1861–1930), a Norwegian polymath who studied hagfishes, explored the Arctic, and later, became a diplomat and humanitarian. He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1922 for his leading role in the repatriation of prisoners of war, in international relief work and as the League of Nations’ High Commissioner for refugees

Ophichthus nansen McCosker & Psomadakis 2018 — a snake eel from Myanmar named for both the EAFNansen Prorgramme and Fridtjof Nansen, for whom the research programme was named. Since 1975, the “EAF-Nansen Programme has contributed to increasing the knowledge of global marine biodiversity while supporting developing countries in fisheries research and sustainable management of their resources throughout surveys at sea and capacity building”

Luthulenchelys McCosker 2007 — a genus of snake eel (Ophichthidae) with one species found off the coast of South Africa. Named in honor of Chief Albert John Mvumbi Luthuli (ca. 1898–1967) of KwaZulu-Natal, former President of the African National Congress. Luthuli won the Peace Prize for his non-violent struggle against apartheid. (Enchelys is Greek for eel)

Etheostoma jimmycarter. Illustration © Joseph R. Tomelleri.

Etheostoma jimmycarter Mayden & Layman 2012 — a darter (Percidae) from Kentucky and Tennessee named for Jimmy Carter, the 39th President of the United States, for his environmental leadership and life-long commitment to social justice. Carter won the Peace Prize in 2002 for his “decades of untiring effort to find peaceful solutions to international conflicts, to advance democracy and human rights, and to promote economic and social development”

Etheostoma gore Mayden & Layman 2012 — a darter (Percidae) from Kentucky and Tennessee named for Al Gore, the 45th vice president of the United States, for his environmental vision, commitment, and accomplishments. Gore and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change jointly won the Peace Prize in 2007 for their “efforts to build up and disseminate greater knowledge about man-made climate change, and to lay the foundations for the measures that are needed to counteract such change”

Etheostoma obama Mayden & Layman 2012 — a darter (Percidae) from Tennessee named for Barack Obama, the 44th president of the United States, for his “environmental leadership and commitment during challenging economic times in the areas of clean energy, energy efficiency, environmental protection and humanitarian efforts globally, and especially for the people of the United States.” Obama won the Peace Prize in 2009 for his “extraordinary efforts to strengthen international diplomacy and cooperation between peoples”

Enteromius mandelai Kambikambi, Kadye & Chakona 2021 — the Eastern Chubbyhead Barb (Cyprinidae) is named for Nelson Mandela (1918–2013), South Africa’s first democratically elected head of state, who was from the Eastern Cape Province where this species is endemic. Mandela won the Peace Prize with F. W. de Klerk in 1993 for their “work for the peaceful termination of the apartheid regime, and for laying the foundations for a new democratic South Africa”

Yes, we realize there may never be a Nobel Prize for Ichthyology.

But that won’t stop The ETYFish Project from delivering the quality content that justifies creating one. 😊

30 October

Five fishes for Halloween

Ghost Hagfish

Myxine phantasma Mincarone, Plachetzki, McCord, Winegard, Fernholm, Gonzalez & Fudge 2021

This hagfish, endemic to the Galápagos Islands, is named for the Greek “phántasma,” an apparition, phantom or ghost. The name refers to its transparent skin, the only species of its genus known to lack melanin-based pigments.

Here’s another ghostly fish from the Galápagos:

Lepidopus manis, holotype, 691 mm male. From: Rosenblatt, R. H. and R. R. Wilson, Jr. 1987. Cutlassfishes of the genus Lepidopus (Trichiuridae), with two new eastern Pacific species. Japanese Journal of Ichthyology 33 (4): 342–351.

Ghost Scabbardfish

Lepidopus manis Rosenblatt & Wilson 1987

This species is known from only one specimen, 691 mm, collected in 1951. Its name is Latin for ghost or soul of the departed, referring to the “ghost-like appearance” of its large eyes.

Most ghosts are spirits of the dead. This fish is a ghost in spirits:

Ghostly Scorpionfish

Scorpaena gasta Motomura, Last & Yearsley 2006

This scorpion fish is endemic to the Eastern Indian Ocean off the southwest coast of Australia. Its name is derived from the Old English “gast,” a spirit or apparition, referring to its “somewhat ghostly appearance” when preserved in alcohol (spirits). “Gast” is also the source of the Middle-English adjective “ghastly,” causing great horror or fear.

One fish that causes great horror or fear is …

Synanceia horrida. Illustration by Johann Friedrich August Krueger. From: Bloch, M. E. 1787. Naturgeschichte der ausländischen Fische. Berlin. v. 3: i–xii + 1–146, Pls. 181–216.

Estuarine Stonefish

Synanceia horrida (Linnaeus 1766)

Stonefishes are among the most dangerous venomous fishes in the world. The spines in its fins act like hypodermic syringes. When handled or stepped on, the spines eject an extremely painful and sometimes fatal venom. The specific name “horrida” means dreadful or frightful but probably does not refer to its danger to humans. Linnaeus borrowed the name from Gronow’s Zoophylacii (1763), where Gronow described the fish’s appearance as “monstrous and horrendous” (translation). The venomous spines were probably unknown to European naturalists at the time.

And, last but not least, a fish named after a monster:

Pink Vent Fish

Thermarces cerberus Rosenblatt & Cohen 1986

This fish, a member of the eelpout family (Zoarcidae), is named for Cerberus, a three-headed dog-like monster in Greek mythology that guarded the gates of Hades. The name alludes to the fish’s type locality, a hydrothermal vent off Mexico in the eastern Pacific, at a depth of 2600 meters. A hellish environment for humans, but not for them.

See the Pink Vent Fish in action at the 2:25 time mark here:

Caesio caerulaurea, at Navy Pier, Exmouth Gulf, Western Australia, September 2017. Source: Alex Hoschke / iNaturalist.org. License: CC by Attribution-NonCommercial.

23 October

Caesio and the smoking gun

I receive comments, corrections and criticisms about my ETYFish entries all the time. Indeed, I welcome and depend upon them. As I say on the site’s intro page, “… if you see anything you believe is incorrect or could be improved upon, please let me know. You are my peer review.” These comments and corrections have improved many entries. But sometimes I receive etymological suggestions that I believe are off the mark. I seriously consider these suggestions and kindly explain to those who proffer them why I disagree. Sometimes my replies are met with resistance. A lively back-and-forth ensues. Caesio is a case in point.

Caesio is a genus of marine ray-finned fishes native to the Indian and western Pacific Oceans known as fusiliers. The genus was formally proposed for the Blue and Gold Fusilier Caesio caerulaurea by the French naturalist Bernard Germain de Lacepède in 1801. Lacepède based his description on unpublished notes written by French naturalist Philibert Commerson (also spelled Commerçon), who first encountered the species during a 1766–1769 voyage around the world. Commerson provided the manuscript name “Caesio,” which Lacepède retained.

The ETYFish entry explains that Caesio is from the Latin caesius, meaning blue, referring to the upper body of C. caerulaurea, described as a “sky blue most pleasant to the eye” (translated from the French). A correspondent whom I shall call Trevor (not his real name) proposed an alternate explanation. He pointed out that “caesius” has two meanings: (1) bluish gray and (2) cutting, sharp. In Latin, he said, “caesio means a cutting of trees, a lopping of trees, a hewing, a wounding, a killing.” He suggested that “caesio” may refer to the scissor-like shape of the fish’s caudal fin: “Scissors are for cutting,” he said. “Caesio may refer to the ‘cut-out’ notch at the center of Caesio caerulaurea’s tail.”

Trevor is correct in stating that “Caesio” has two different meanings, as the Wiktionary page for the word indicates. But Trevor is incorrect in suggesting that the name refers to the tail when Lacepède explicitly mentioned what the name means, and credited Commerson as the source: “Le naturaliste voyageur a tiré ce nom de caesio, de la couleur bleuâtre, en latin caesius, de l’animal qu’il avoit sous ses yeux.” (“The traveling naturalist took this name caesio, from the bluish color, in Latin caesius, of the animal he had before his eyes.”) Is there any ambiguity here? Is there any wiggle room for an alternative explanation? No. In this case, caesio clearly means blue, or bluish gray, and refers to the color of the fish.

I explained to Trevor that when researching fish-name etymologies, one must always consult the original description in which the name was proposed. If the author explains what the name means, then that is what the names means, even if the Latin or Greek words behind the name may have alternate meanings. I also pointed out that at least seven other fish species have “caesius” in their names, all referring to bluish gray.

Trevor remained unconvinced, saying that he is “restless” about Lacepède’s text. “There was more than 30 years between Commerson’s discovery and Lacépède’s description,” he told me, “plenty of time for misunderstanding to develop.” He concluded with these words: “I’m sticking with my side until I see smoking-gun evidence for your side.”

Always up for a fun etymological challenge, I acquired the smoking gun.

During my correspondence with Trevor, I learned that a fellow fish historian was studying Commerson’s original manuscripts for an upcoming monograph. The manuscripts are housed at the Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle in Paris. I asked my colleague for a scan of Commerson’s notes on Caesio, which he promptly dispatched. On the last page of a 14-page handwritten manuscript, Commerson wrote: “Etymon Caesionem diximus habita ratione coloris caerulescentis sive Caesii in hoc pisce & forte congeneribus praedominantis.”

My translation:

“We have given the etymology of Caesio, taking into account the blue color, or Caesius, of this fish, and perhaps predominating in its congeners.”

I sent the smoking gun to Trevor. He acknowledged its receipt but as of this writing, over 11 weeks later, I have not seen a reply.

What’s my point in telling you all this? It’s this:

I spend a lot of time focusing on the things I’ve gotten wrong at ETYFish, or could have done better. When I completed my first run through of all the fishes in 2021, I considered the site a “solid first draft.” I’ve been revising and tinkering and polishing ever since. More importantly, I’ve never stopped learning. My understanding of Greek and Latin has improved. I know more about the origins of fish names that date to ancient Greece, the Renaissance and other pre-Linnaean publications. And I simply know more about the fishes themselves (and the people who’ve named them), over 37,000 species and counting. And thanks to Trevor and others like him, who care enough to take the time to note the flaws both big and small, the site gets a little bit better every day.

But when you spend so much time on the things you’ve gotten wrong, you tend to lose sight of the things you’ve gotten right. In the case of Caesio, I knew my explanation was correct and had incontrovertible evidence to back it up. So, please, allow me the opportunity to gloat just this once. As soon as I post this Name of the Week, I will humbly return to the long and never-ending list of corrigenda still waiting to be addressed.

16 October

Ophisternon berlini Arroyave, Angulo, Mar-Silva & Stiassny 2024

Ophisternon berlini. From: Arroyave, J., A. Angulo, A. F. Mar-Silva, and M. L. J. Stiassny. 2024. A new endogean, dwarf, and troglomorphic species of swamp eel of the genus Ophisternon (Synbranchiformes: Synbranchidae) from Costa Rica: evidence from comparative mitogenomic and anatomical Data. Ichthyology & Herpetology 112(3): 375–390.

If you’re ever in the Costa Rican rainforest, watch your step. There could be a new species of swamp eel “swimming” underfoot.

The recently described Ophisternon berlini was first encountered in 2021, when excavation work at the Las Brisas Nature Reserve in Limón, Costa Rica, uncovered two unfamiliar swamp eels (family Synbranchidae) maneuvering through the mud. Researchers, suspecting it was a new species, returned to the nature reserve in 2022 and 2023 to search for more. Their collection technique involved digging up blocks of mud and sifting through the dirt. They found five more specimens living about 61 cm below the swampy and muddy rainforest floor.

Despite the common name “swamp eel,” synbranchids are not true eels. They’re simply called eels because of their eel-like shape. With 30 species in seven genera, synbranchids have a remarkable discontinuous distribution across five continents: Africa, Asia, Australia, and both North and South America. Most species burrow in the muck of marshes and swamps. Two species live in caves. Ophisternon berlini joins a very small list of “endogean” fishes, that is, fishes that dwell in soil. The other two are also synbranchids: Rakthamichthys rongsaw of northeast India and Typhlosynbranchus luticolus of Cameroon.

Ophisternon berlini is a diminutive fish, reaching just under 16 cm in length, with a worm-like body, no fins, a pointed head, large teeth, and very small eyes covered with thick skin. Like other animals that live in darkness, these swamp eels have very little pigment in their skin. Instead, their pinkish color comes from the muscles visible inside their bodies.

Ophisternon berlini is the seventh valid species in the genus. British physician and ichthyologist John McClelland (1805–1875) proposed the genus in 1844 (possibly 1845) for Ophisternon bengalense, a wide-ranging species from India to the Mekong River basin of Cambodia and Vietnam, and the Philippines. The name is a combination of the Greek óphis (ὄφις), serpent, and stérnon (στέρνον), breast or chest, referring to how the trunk of the fish is “formed like that of a snake.”

The specific epithet berlini honors Erick Berlin, “a strong supporter of conservation and scientific research of Costa Rican biodiversity,” who first encountered this species and owns the nature reserve where it lives.

9 October

9 October

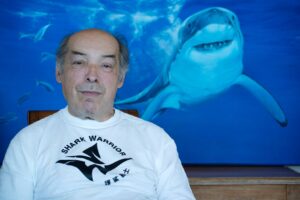

Leonard J. V. Compagno (1943–2024)

This week we mourn the loss of Leonard J. V. Compagno, who passed away on September 25.

Dr. Compagno was a true giant in the field of chondrichthyan fish taxonomy. He described or co-described six new genera and 20 new species of sharks, three genera and 12 new species of rays, and three new species of chimaeras.

Much of Dr. Compagno’s early work established the framework and foundation for modern chondrichthyan classification, still followed today. And his two-volume Sharks of the World (1984 and 2001) for the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, despite its age, is still a go-to reference today.

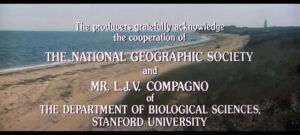

Dr. Compagno was even a movie star of sorts. While he was a graduate student at Stanford University, he was hired by Steven Spielberg for help in making sure the mechanical Great White Shark built for the 1975 blockbuster Jaws was anatomically correct. Compagno is prominently thanked in the final frames of the film.

Dr. Compagno was even a movie star of sorts. While he was a graduate student at Stanford University, he was hired by Steven Spielberg for help in making sure the mechanical Great White Shark built for the 1975 blockbuster Jaws was anatomically correct. Compagno is prominently thanked in the final frames of the film.

Two species from off the coast of South Africa (where Compagno lived and conducted most of his research) have been named in his honor:

Brown Lantershark Etmopterus compagnoi Fricke & Koch 1990 — for Compagno’s research on South African sharks

Tigertail Ray Leucoraja compagnoi (Stehmann 1995) — for Compagno’s “fundamental contributions to chondrichthyan systematics, mainly on sharks, and his research devoted to South African chondrichthyans”

There will probably be more.

Fellow shark expert David A. Ebert wrote, “Leonard was a once in a generation researcher in our field whose contributions will influence generations to come.”

2 October

2 October

Clyde D. Barbour (1935–2023)

Late last week I learned from ichthyologist Tyson R. Roberts that American ichthyologist Clyde D. Barbour passed away nearly a year ago on 17 October 2023 after a long illness. He was 87.

Dr. Barbour earned his Ph.D. from Tulane University in 1966. His research focused on the fishes of the Central Plateau of Mexico. In 2000, he was honored by the Mexican Society of Ichthyology in Mexico City for his research contributions. He taught at the University of Utah, Mississippi State University, and Tuskegee University (Alabama), and was a professor emeritus from Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio. During many winters in retirement, he was a visiting scientist in the Fish Division of the University of Michigan Museum of Zoology.

Fish taxa described or co-described by Dr. Barbour include chubs of the Mexican genus Algansea and silversides of the Neotropical genus Chirostoma.

Algansea aphanea Barbour & Miller 1978 aphanḗs (Gr. ἀφανής), invisible, secret or unknown, referring to the “considerable osteological differences separating it from other barbeled species of Algansea”

Algansea avia Barbour & Miller 1978 Latin for out of the way or re-mote, being the most western species of Algansea

Algansea monticola Barbour & Contreras-Balderas 1968 montis (L.), mountain, –cola (L.), dweller or inhabitant, referring to the “rugged nature” of the area in which it occurs in Zacatecas, Mexico

Algansea monticola archidion Barbour & Miller 1978 –idion (Gr. -ἴδιον), diminutive suffix: archídion (Gr. ἀρχίδιον), diminutive of archḗ (ἀρχή), principal or chief, here, per the authors, meaning petty office or position, referring to its subspecific status

Chirostoma aculeatum Barbour 1973 Latin for sharp-pointed or stinging, referring to its long, pointed snout

Chirostoma contrerasi Barbour 2002 in honor of Barbour’s friend and colleague Salvador Contreras-Balderas (1936–2009), for his many contributions to the study of the systematics, evolution and conservation of Mexican fishes

Chirostoma contrerasi Barbour 2002 in honor of Barbour’s friend and colleague Salvador Contreras-Balderas (1936–2009), for his many contributions to the study of the systematics, evolution and conservation of Mexican fishes

Dr. Barbour’s final contribution to ichthyology was co-authoring the chapter on New World Silversides (Atherininopsidae) in the 2020 book Freshwater Fishes of North America: Characidae to Poeciliidae.

Hippocampus nalu © Richard Smith, OceanRealmImages.com

25 September

Hippocampus nalu Short, Claassens, Smith, de Brauwer, Hamilton, Stat & Harasti 2020

The name of this pygmy seahorse from South Africa has three etymologies:

(1) It’s named for the word “nalu,” which means “here it is” in the South African languages of Xhosa and Zulu, referring to how this species “was there all along until its discovery.” In fact, this diminutive fish — less than 2.7 cm — is the first pygmy seahorse from the Indian Ocean and the coast of Africa. (Its closest relatives live more than 8,000 km away in Southeast Asia.)

(2) It’s named in honor of Savannah Nalu Olivier, a dive instructor who noticed a tiny seahorse she couldn’t identify during one of her dives in South Africa’s Sodwana Bay, a popular diving destination. Subsequent dives by ichthyologists confirmed it was an undescribed species.

(3) It’s named for the Hawaiian word “nalu,” meaning waves or surf of the moana (ocean), referring to its habitat. The reefs of Sodwana Bay are exposed to the powerful swells of the Indian Ocean, unlike the sheltered coral reefs of Southeast Asia where the other pygmy seahorses are found. Ichthyologists found a pair along a rocky reef at 15m depth, grasping onto fronds of microscopic algae amidst the raging surge.

It’s three, three, three names in one!

18 September

Fishes by Anonymous Part II

As stated last week, it wasn’t uncommon for animals to be named anonymously in the early years of Linnaean zoological nomenclature. The following “anonymous” fish taxa have an unusual bibliographic pedigree.

Glaucostegus thouin (Anonymous 1798), Clubnose Guitarfish named in honor of French botanist André Thouin (1746–1824), who helped secure a specimen in Holland and transported it to France [a noun in apposition, without the patronymic “i”]

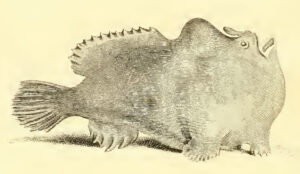

“La lophie Commerson.” From: Lacepède, B. G. E. 1798. Histoire naturelle des poissons. v. 1: 1–8 + i–cxlvii + 1–532, Pls. 1–25, 1 table.

Antennarius commerson (Anonymous 1798), Giant Frogfish named in honor of French naturalist Philibert Commerçon (also spelled Commerson, 1727–1773), whose unpublished notes on this fish informed its description

Sphoeroides Anonymous 1798, pufferfish genus -oides, Neo-Latin from eī́dos (Gr. εἶδος), form or shape: sphaī́ra (Gr. σφαῖρα), ball or sphere, referring to round shape when fish is inflated with air or water, especially when viewed from the front

Arothron meleagris (Anonymous 1798), Guineafowl Puffer meleagrís (Gr. μελεαγρίς), guineafowl, referring to innumerable white spots on body, which resembles color pattern of a guineafowl

Arothron stellatus (Anonymous 1798), Starry Puffer Latin for studded with stars, referring to stellate (arranged in a radiating pattern like that of a star) prickles that cover its body

Abalistes stellatus (Anonymous 1798), Starry Triggerfish Latin for studded with stars, described as having small white spots on its upper body

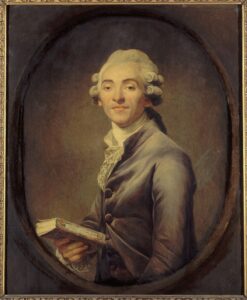

Portrait of Bernard Germain de Lacepède by Joseph Ducreux ca. 1785.

All of these taxa were described by French naturalist Bernard Germain de Lacepède (1726–1825) in the first volume of Histoire naturelle des poissons. The names of many currently valid fish taxa date to Lacepède’s five-volume work, but none to volume one. Why? Because for some reason Lacepède provided only French vernacular names …

la raie Thouin

la lophie Commerson

les Sphéroïdes

le baliste étoilé

le tétrodon méléagris

te tétrodon étoile

… not Latin names, for the taxa described in that volume

Instead, the formal Latin names date to a two-part anonymous book review published later in 1798 in a German literary magazine, Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung. The anonymous reviewer provided Latin equivalents of the French vernaculars. Those Latin equivalents were picked up by other naturalists in subsequent works and became established in the literature. For this reason, an anonymous book reviewer is credited as being the “author” of these names. Sticklers for authorial accuracy would say “Anonymous (ex Lacepède) 1798” is a more informative citation.

11 September

Fishes by Anonymous Part I

Chaetodon rafflesii, Pemuteran, Bali, Indonesia. Photo by Bernard E. Picton. Courtesy: Wikipedia.

In the early years of Linnaean zoological nomenclature, it wasn’t uncommon for names to be proposed in anonymous publications. In subsequent literature and databases, the author of these names is simply given as “Anon.” or “Anonymous” followed by the publication date. Should the name of the author be revealed through external evidence, the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) recommends that it be enclosed in square brackets to show the original anonymity. Among fishes, the most prolific “anonymous” author of currently valid fish taxa is British zoologist Edward Turner Bennett (1797–1836).

- Chiloscyllium plagiosum (Anonymous [Bennett] 1830) – Whitespotted Bamboo Shark (Hemiscylliidae)

- Atelomycterus marmoratus (Anonymous [Bennett] 1830) – Coral Catshark (Atelomycteridae)

- Glaucostegus typus (Anonymous [Bennett] 1830) – Common Shovelnose Ray (Glaucostegidae)

- Ophichthus apicalis (Anonymous [Bennett] 1830) – Bluntnose Snake Eel (Ophichthidae)

- Ilisha elongata (Anonymous [Bennett] 1830) – Chinese Herring or Slender Shad (Pristigasteridae)

- Herklotsichthys ovalis (Anonymous [Bennett] 1830) – a Western Pacific shad or herring (Dorosomatidae), no types known

- Hemiarius sumatranus (Anonymous [Bennett] 1830) – Goat Catfish (Ariidae)

- Carangoides praeustus (Anonymous [Bennett] 1830) – Brownback Trevally (Carangidae)

- Ichthyscopus malacopterus (Anonymous [Bennett] 1830) – a stargazer (Uranoscopidae) from the Western Central Pacific

- Chaetodon rafflesii Anonymous [Bennett] 1830 – Latticed Butterflyfish (Chaetodontidae)

- Monotaxis Anonymous [Bennett] 1830 – a genus of emperor breams (Lethrinidae) from the Indian and western Pacific Oceans

Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles. 1824 Engraving by J. Thompson.

Why the anonymity? I’m not sure. The descriptions of the above-listed species all appeared in the 1830 book Memoir of the life and public services of Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles. Raffles (1781–1826) was a British colonial official who served as the governor of the Dutch East Indies between 1811 and 1816. He also played a key role in the founding of modern Singapore. What’s more, Raffles was seriously interested in natural history. He employed zoologists and botanists to collect Southeast Asian specimens, paying them out of his own pocket. He described two species himself (a macaque and a mouse-deer) and was the first President of the Zoological Society of London. His natural history collection became the Raffles Museum in 1849, now known as the National Museum of Singapore. (The natural history collection has since been moved to the Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum.)

The 1830 memoir was written by Raffles’ widow. It contains a long appendix, “Catalog of Zoological Specimens,” in which the many animal species collected under Raffles’ supervision are listed and provided with brief natural history accounts. Smaller and lesser-known specimens are formally described and named. Edward Turner Bennett penned the nine pages on fishes but for some reason he is not given credit in the book. Bennett named one of the fishes after Raffles, apparently saving the eponym for the loveliest one: the Latticed Butterflyfish Chaetodon rafflesii (shown above).

Not much is known about Edward Turner Bennett. His entry at the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography is short: “Bennett, Edward Turner (1797–1836), zoologist, was born in Hackney, Middlesex, on 6 January 1797, the son of Edward Turner Bennett (1758–1843) and his wife, Lucy, née Ball (bap. 1775, d. 1859). He was the elder brother of the botanist John Joseph Bennett (1801–1876). He practised as a surgeon in Portman Square, having been a pupil at the anatomy school operated by the surgeon Joshua Brookes. Bennett was interested in zoology and became a prominent member of the Zoological Club of the Linnean Society. In 1828 he became vice-secretary.”

Why he died so young (age 39) is not explained.

Next week, Anonymous Fishes Part II.

4 September

Cambeva damnata Costa, Azevedo-Santos, Ottoni, Vilardo & Katz 2024

Cambeva damnata, holotype, 46.5 mm SL. From: Costa, W. J. E. M., V. M. Azevedo-Santos, F. P. Ottoni, P. J. Vilardo and A. M. Katz. 2024. A new species of the Cambeva variegata group (Siluriformes: Trichomycteridae) from the Serra do Espinhaço, south-eastern Brazil, under severe risk of extinction. Zootaxa 5497 (3): 426–434.

We should all dislike names such as this one. Not for the name itself. But for what the name represents.

Cambeva damnata is a new species of trichomycterid catfish that lives buried under rocks and gravel, known only from two small urban streams in Minas Gerais State of southeastern Brazil. The word “urban” is key to the species’ name … and its continued existence on this planet. At one of the collecting sites, the stream banks are heavily deforested. Homes line the banks and sewage is dumped directly into the stream. In addition, the headwaters of the catfish’s habitat are exposed to nearby mining, causing siltation, destruction of riparian vegetation, and water contamination downstream. These three factors — extremely limited range, urbanization and mining — condemn this catfish to an all but certain extinction. Hence the name:

Damnata is Latin for condemned.

What does Cambeva mean? Proposed by Katz, Barbosa, Mattos & Costa in 2018, Cambeva is a local name for trichomycterid catfishes in southern and southeastern Brazil. It is derived from the Tupi words a’kãg, meaning head, and pewa, flat, referring to their dorsally flattened heads. Cambeva damnata is the 56th described species in the genus.

28 August

Takifugu Abe 1949 — better late than never

Takifugu oblongus. Lithograph by C. Achilles. From: Day, F. 1878. The fishes of India; being a natural history of the fishes known to inhabit the seas and fresh waters of India, Burma, and Ceylon. Part 4: i–xx + 553–778, Pls. 139–195.

It took four years for the correction to be made. I am not sure why it took so long. I found the mistake and alerted Eschmeyer’s Catalog of Fishes (ECoF) in August 2020. The editors agreed with my finding and said it would be fixed. And then it slipped through the cracks, mine and theirs. I never made the correction in ETYFish. And ECoF didn’t post the correction until two weeks ago, on 13 August. ETYFish has since been corrected as well. Better late than never.

Takifugu is a genus of pufferfishes with around 23 species from marine and brackish waters of the northwest Pacific and Indo-Pacific oceans, including a few freshwater species in Asia. The genus was proposed (as a subgenus of Sphoeroides) by Japanese ichthyologist Tokiharu Abe (1911–1996) in 1949. Taki-fugu is the Japanese name for the type species T. oblongus. Fugu means pufferfish (literally “river pig”). The meaning of taki is unclear. According to FishBase, it means “to be cooked in liquid.” Whatever the meaning, it should be cooked carefully, since T. oblongus, like all members of the genus, contains lethal amounts of the poison tetrodotoxin.

At some point, ECoF editors changed the authorship of Takifugu from Abe 1949 to Marshall & Palmer 1950, citing ICZN Art. 13.3, which states that every new genus-group name published after 1930 must be accompanied by the fixation of a type species in the original publication (or be expressly proposed as a new replacement name) in order to be available. Since Abe 1949 allegedly did not assign a type species, the name then dates to the first taxonomists who did, in this case Marshall & Palmer 1950, who recorded T. oblongus as the type species in the Zoological Record for 1949 (published 1950).

When I consulted Abe’s original description of Takifugu while researching the etymology of its name, I noticed that T. oblongus was the only species Abe assigned to the (then) subgenus. Since Takifugu was proposed as a monotypic genus-level name, i.e., with only one species, the type species is fixed by “indication.” In other words, the type species is automatically T. oblongus. Had Abe proposed Takifugu with two or more species, he would have needed to explicitly mention which one is the type. Based on this information, “Abe 1949” should be reinstated as the author of the genus.

Why did this mistake happen in the first place? The ECoF entry for Takifugu in August 2020 (since deleted but I saved a copy) provided a clue. According to that entry, Abe had actually proposed Takifugu for more than one species 10 years earlier, in 1939, but did not assign a type. I checked Abe 1939 and was surprised to see that Takifugu was not mentioned at all. Instead, Abe had proposed the similarly-named Torafugu for two species without type fixation. (Abe indicated a type in 1950 and later decided the two genera were the same.) My guess is that whoever entered the ECoF data simply confused Torafugu with Takifugu.

Japan’s Health Ministry states that up to 50 people get sick every year by eating incorrectly prepared fugu. A “few” of these people die. To date, no one has gotten sick nor died because of incorrectly entered data at Eschmeyer’s Catalog of Fishes and The ETYFish Project.

21 August

Tadpole fishes

Several fish taxa have been named for their resemblance to larval frogs, or tadpoles, with their large, rounded head followed by a thin body or tail. Most of these “tadpole fishes” are named, or have names derived from, gyrinus, a Latinization of gyrí̄nos (γυρῖνος), the Greek word for tadpole.

Several fish taxa have been named for their resemblance to larval frogs, or tadpoles, with their large, rounded head followed by a thin body or tail. Most of these “tadpole fishes” are named, or have names derived from, gyrinus, a Latinization of gyrí̄nos (γυρῖνος), the Greek word for tadpole.

The first piscine “gyrinus” was the Tadpole Madtom Noturus gyrinus, a small catfish (Ictaluridae) from southern Canada, and eastern and central USA. It was named by American politician-naturalist Samuel Latham Mitchill (1764–1831) in 1817. Mitchill said the fish’s lanceolate tail resembles that of a tadpole.

Others (not an exhaustive list) include:

Gyrinichthys Gilbert 1896 — This name literally means “tadpole fish.” It’s a genus of Snailfishes (Liparidae) from the Bering Sea. American ichthyologist and fisheries biologist Charles H. Gilbert (1859–1928) did not provide an etymology, nor an illustration, but G. minytremus (the only species), definitely resembles a tadpole in shape.

Gyrinocheilus Vaillant 1902 — The Algae Eater genus (of aquarium fame) is named for the shape of the cheilus (from cheī́los, χεῖλος), Greek for lip, having the “somewhat triangular appearance of the mouth of the tadpole” (translation).

Ebinania gyrinoides (Weber 1913) — “-oides” is a common suffix in zoological nomenclature. It’s a Latinization of the Greek eī́dos (εἶδος), meaning form or shape. German-born Dutch physician and zoologist Max Weber (1852–1937) described this Flathead (Psychrolutidae) from the Western Pacific, saying that its body is “strikingly similar to that of a frog larva” (translation).

Gyrinomimus myersi. From: Parr, A. E. 1934. Report on experimental use of a triangular trawl for bathypelagic collecting with an account of the fishes obtained and a revision of the family Cetomimidae. Bulletin of the Bingham Oceanographic Collection Yale University v. 4 (art. 6): 1-59.

Gyrinomimus Parr 1934 — This genus of Flabby Whalefishes (Cetomimidae) occurs in deeper waters (1280–2791 m) of the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea. Marine biologist Albert Eide Parr (1900–1991) named it Gyrinomimus — gyrí̄nos + mimus, Latin for imitator or mimic — referring to the tadpole-like head of the type species G. myersi.

Listrura gyrinura Costa, Feltrin & Katz 2023 — This trichomycterid catfish from Brazil is named for the tadpole-like shape of its ourá (οὐρά), Greek for caudal fin, and caudal peduncle.

Careproctus ranula (Goode & Bean 1879) — Not all “tadpole fishes” are named gyrinus. This one, the Scotian Snailfish (Liparidae) from the Western North Atlantic, is named ranula, a diminutive of rana, Latin for frog, i.e., a little or baby frog, referring to its tadpole-like shape, with a thick head, quickly tapering to the tail.

Careproctus ranula. From: Goode, G. B. and T. H. Bean. 1896. Oceanic ichthyology, a treatise on the deep-sea and pelagic fishes of the world, based chiefly upon the collections made by the steamers Blake, Albatross, and Fish Hawk in the northwestern Atlantic, with an atlas containing 417 figures. Special Bulletin U. S. National Museum No. 2: Text: i–xxxv + 1–26 + 1–553, Atlas: i–xxiii, 1–26, 123 pls.

Chlamydogobius ranunculus Larson 1995 — Here’s another “rana” derived name, in this case the actual Latin word for tadpole or little frog. “Gobiologist” Helen Larson named this Australian goby (Oxudercidae) after the tadpole for the “resemblance to which this rather frog-headed goby displayed to the author upon their first encounter, at the edge of a drying-up water buffalo wallow.”

Interestingly, there is one fish named “gyrinus” that is not named after a tadpole, although the names are etymologically related. In 2003, Chavalit Vidthayanon and Heok Hee Hg described Acrochordonichthys gyrinus, an akysid catfish from the Chao Phraya basin of Thailand. They say “gyrinus” is Latin for “rounded or curved,” referring to the concave posterior margin of the fish’s pectoral fin. As it turns out, “gyrinus” (tadpole) is derived from the Greek gyrós (γυρός), originally meaning rounded or curved, referring to its rounded head.

Tatia gyrinus. From: Eigenmann, C. H. and W. R. Allen. 1942. Fishes of Western South America. I. The intercordilleran and Amazonian lowlands of Peru. II. The high pampas of Peru, Bolivia, and northern Chile. With a revision of the Peruvian Gymnotidae, and of the genus Orestias. University of Kentucky. i–xv + 1–494, Pls. 1–22.

The reason I began looking into tadpole-inspired fish names was to determine the proper spelling of Centromochlus gyrinus, an Amazonian catfish (Auchenipteridae) described by Carl H. Eigenmann (1863–1927) and William Ray Allen (1885–1955) in 1942. (Eigenmann began the manuscript, lost in aboard a train; it was located in the lost-and-found after Eigenmann’s death and completed by his student Allen.) The authors did not provide an etymology, nor did they mention “tadpole” or anything rounded or curved in their description, but their accompanying illustration (shown here) shows what could be described as a tadpole-shaped fish, especially its large head. In 1974, Dutch ichthyologist-ornithologist Gerloff F. Mees (1926–2013) reassigned Centromuchlus gyrinus to the genus Tatia. Since Tatia is a feminine genus (whereas Centromuchlus is masculine), Mees changed the spelling from gyrinus to gyrina, apparently believing the name to be an adjective and, hence, needing to agree in gender with the genus. That spelling, Tatia gyrina, has remained in usage until earlier this month, when I took a closer look.

Considering all the fish taxa named for the Latin noun gyrinus (including several not mentioned above), I believe Eigenmann & Allen named their catfish in the same manner. In addition, per ICZN 31.2.2, if the origin of a zoological name is uncertain, it is to be treated as a noun. Since the spellings of nouns are not emended to agree with the gender of the genus, I contend that Eigenmann & Allen’s original spelling should be retained. I sent these comments to the editors of Eschmeyer’s Catalog of Fishes (ECoF) and they agreed. As 13 August 2024, ECoF changed the spelling of Tatia gyrina to Tatia gyrinus.

Finally, what’s the etymology of “tadpole”? It’s a cute word. Where did it come from? According to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), it’s from the Middle English tāde or tadde, meaning toad, and the Middle English poll, meaning head or roundhead (although the latter element has been questioned since “toadhead” doesn’t quite make sense when describing a larval frog). Another English word for tadpole is pollywog, derived (per the OED) from poll, head, and wog, from wiggle. “Wiggling head” is an apt description of a tadpole.

14 August

Oncorhynchus gorbuschka Glubokovsky & Zhivotovsky 2024

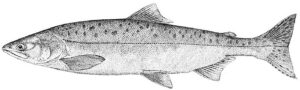

Oncorhynchus gorbuschka, holotype, female. From: Glubokovsky, M. K. and L. A. Zhivotovsky. 2024. A new species of Pacific salmon—Rosy Salmon Oncorhynchus gorbuschka sp. nova: description and genesis of the taxon. Russian Journal of Marine Biology 50 (3): 116-125. Russian version in Biologiya moray 50 (no. 2).

This is the first time I’ve seen a fish named this way, and I’m not sure that I like it.

Oncorhynchus gorbuscha (Walbaum 1792) is the Pink or Humpback Salmon, which occurs in coastal regions from the Northwest Territory of Canada, northwest around Alaska to Puget Sound (USA), with strays as far south as Monterey Bay (California), and in Eurasia, with spawning populations from North Korea, north to the Arctic Ocean, and west to Russia’s Lena River. It’s also been introduced into the upper Great Lakes of North America. The specific epithet gorbuscha is derived from gorbúša, a Russian word for humpback, referring to the pronounced humped back of males during their spawning migration.

Russian ichthyologists have now described a closely related cryptic species that co-occurs with O. gorbuscha in the Kamchatka Peninsula of Russia. Although the two species are distinguished by morphological data and genetic markers, the most striking difference between them is that new species spawns only in odd years, whereas O. gorbuscha spawns in even years.

The name of the new species is the same as the existing species except for the addition of the letter “k” — gorbuschka instead of gorbuscha. The authors say this name “emphasizes their crypticity and close phylogenetic relationship.” The common name is Rosy Salmon.

There are other examples in fishdom in which names differ by one letter (see NOTW 5 April and 12 April 2024). But these were unintentional. This, I believe, is the first time an existing name is intentionally changed by one letter to nomenclaturally link two genetically and geographically linked species.

I appreciate what the new name is trying to say but I’m not sure I like it because the potential for confusion is great. At first glance, the names “gorbuscha” and “gorbuschka” look pretty much the same. I would have preferred something along the lines of “pseudogorbuscha,” “hemigorbuscha” or “impargorbuscha” (“odd gorbuscha”), which would have communicated the same information in a more orthographically distinctive way.

On the other hand, since the two species are nearly identical, maybe their names should be as well. In which case, the new name is perfect.

7 August

Stiphodon chlorestes Jhuang, Dimaquibo & Liao 2024

Here’s a lovely name for a lovely fish.

Stiphodon chlorestes is a new species of goby (Oxudercidae) from freshwater streams not far from the ocean in northern and eastern Taiwan and northern Luzon Island, Philippines. It was discovered and photographed by aquarium hobbyists in 2012, but specimens were not preserved. In 2022, two female and five male individuals were obtained and examined by ichthyologists. Morphological and molecular evidence show that the goby is distinct from any known Stiphodon, a fairly diverse genus of gobies (now 33 species), widely distributed in tropical and subtropical freshwater streams from Sri Lanka and the western coast of Sumatra in the Indian Ocean to southern Japan, north-eastern Australia, and French Polynesia in the Pacific Ocean. Stiphodon are amphidromous, which means pelagic larvae drift from freshwater into an estuary or ocean to feed and grow, and then juveniles return to freshwater to grow and reproduce (not to be confused with anadromy, in which fish are born in freshwater but migrate to the ocean as juveniles, not larvae, and then return to freshwater as adults, e.g., as Pacific salmons).

The ichthyologists — Wei-Cheng Jhuang, Al Casane Dimaquibo and Te-Yu Liao — named the goby for the hummingbird genus Chlorestes, referring to how the goby often quickly flapps its pectoral fins in the middle column of the water, like a hovering hummingbird with its rapidly flapping wings (as shown in this brief video, which the authors linked to in the “Etymology” section of their description). In addition, males have a metallic turquoise head and chartreuse body sides, similar to the plumage of the hummingbird Chlorestes cyanus.

Bird name aficionados will tell you that Chlorestes is a combination of the Greek chlōrós (χλωρός), green, and esthḗs (ἐσθής), dress, clothing or raiment, referring to the green plumage of the type species, Chlorestes notata, a hummingbird species from South America.

The goby genus Stiphodon was proposed by the German-born Dutch physician and zoologist Max Weber (1852–1937) in 1895. The name is a combination of the Greek stī́phos (στῖφος), meaning dense pile, heap or pack, and odon, Latinized from the Greek odoús (ὀδούς), meaning tooth, referring to the closely packed teeth in the upper lip of the type species, S. semoni.

31 July

Enteromius niggie Scheepers, Bragança & Chakona 2024

This fish’s name doesn’t mean what you think it might mean.

In 1962, English ichthyologist Peter Humphry Greenwood (1927–1995), Curator of the Fish Section of the British Museum, described a new species of goldie barb from Zimbabwe, Barbus (now Enteromius) neefi. Greenwood did not explain the meaning of the name “neefi.”

In May 2011, while working on names of the family Cyprinidae, I sent an email to Paul Skelton, the foremost authority on the freshwater fishes of southern Africa, asking if he had any idea what “neefi” means. He had more than an idea; he knew the entire story!

As explained by Dr. Skelton, Greenwood coined the name as a humorous and personal reference to ichthyologist Graham Bell-Cross (1927–1998), Zambia Department of Game and Fisheries. Bell-Cross called Greenwood “oom,” an Afrikaans word meaning uncle. Bell-Cross also collected the types of the new species and sent them to Greenwood for identification. So “Uncle” Greenwood named the species “neefi” from neef, the Afrikaans word for nephew or male cousin.

General body features and live coloration of Enteromius niggie. (a) Male during breeding season. (b) Male during non-breeding season. From: Scheepers, M., Bragança, P. H. N., & Chakona, A. 2024. Naming the other cousin: A new goldie barb (Cyprinidae: Smiliogastrininae) from the northeast escarpment in South Africa, with proposed taxonomic rearrangement of the goldie barb group in southern Africa. Journal of Fish Biology, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfb.15870

Sixty-plus years later, three researchers from NRF-South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity) — Martinus Scheepers, Pedro H. N. Bragança and Albert Chakona — took a closer look at the unusual disjunct distribution of E. neefi, divided between rivers in the northeast escarpment in South Africa and Eswatini, and tributaries of the Upper Zambezi in Zambia and southern Congo in the Democratic Republic of Congo, with a large geographic gap between these two populations. Using molecular and morphological methods, the researchers examined the level of divergence between the two populations and determined that specimens from the Steelpoort River in the Limpopo River system of South Africa represented a new species.

The specific epithet niggie — from the Afrikaans word for niece or female cousin — is a “symbolic representation of the historical association” between it and E. neefi, which had been considered to represent disjunct populations of the same species. The name is pronounced nᶕᶍi, with a hard guttural sound at the back of the throat.

The meaning of the generic name Enteromius, proposed by Edward Drinker Cope in 1867, is not clear. It appears to be derived from the Greek énteron (ἔντερον), meaning intestine, referring to the short alimentary canal of E. potamogalis (see NOTW, 16 July 2014).

24 July

William D. Anderson, Jr. (1933–2024)

This week we report the sad news that ichthyologist William D. Anderson, Jr., of the Grice Marine Laboratory (College of Charleston), passed away on 17 July in Charleston, South Carolina. Over the course of a long and distinguished career, Dr. Anderson specialized in the systematics of slopefishes (Symphysanodontidae), anthias and fairy basslets (Anthiidae), splendid perches (Callanthiidae), and snappers (Lutjanidae). He described or co-described five new genera and 22 new species.

This week we report the sad news that ichthyologist William D. Anderson, Jr., of the Grice Marine Laboratory (College of Charleston), passed away on 17 July in Charleston, South Carolina. Over the course of a long and distinguished career, Dr. Anderson specialized in the systematics of slopefishes (Symphysanodontidae), anthias and fairy basslets (Anthiidae), splendid perches (Callanthiidae), and snappers (Lutjanidae). He described or co-described five new genera and 22 new species.

One name is especially interesting. In 2017, Dr. Anderson, along with G. David Johnson, described the Barred Groppo Grammatonotus pelipel (Callanthiidae) from Pohnpei Island, part of the Caroline Islands group, in the western Pacific Ocean. “Pelipel” is the Pohnpeian word for “tattoo” or “to tattoo,” referring to how barring on the sides of the young specimens resembles many Pohnpeian tattoos.

Grammatonotus pelipel, paratype, 28.1 mm SL. Photo by Brian D. Greene. From: Anderson, W. D., Jr. and G. D. Johnson. 2017. Two new species of callanthiid fishes of the genus Grammatonotus (Percoidei: Callanthiidae) from Pohnpei, western Pacific. Zootaxa 4243 (1): 187–194.

In addition to his systematic work, Dr. Anderson was also superb historian, publishing important works on the history of natural history investigations in South Carolina, and two books with Theodore W. Pietsch: Collection Building in Ichthyology and Herpetology (1997) and Ichthyopedia: A Biographical Dictionary of Ichthyologists (2023).

Dr. Anderson grew up in Columbia, South Carolina. He earned a B.S. in Biology ’53, an M.S. in Biology ’55, and a Ph.D. ’60 from the University of South Carolina. After graduation he worked as an Assistant Professor at Susquehanna University, as a fishery biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, as an Assistant Professor at the University of Florida, as an Associate Professor at the University of Chattanooga, Tennessee, and as a Professor at the College of Charleston. He was instrumental in starting the fish collection at the Grice Marine Lab.

Two fishes have been named in Dr. Anderson’s honor.

In 1974, Swiss ichthyologist Adolf Kotthaus described the Buck-toothed Slopefish Symphysanodon andersoni from the northwest Indian Ocean. Anderson was recognized for his work on the genus, his examination of this holotype, and for sharing his findings with Kotthaus.

In 1982, American ichthyologists John E. McCosker and James E. Böhlke described a new genus and species of snake eel, Lethogoleos andersoni, from off the coast of Anderson’s beloved South Carolina. The generic name is a combination of the Greek lḗthē (λήθη), forgetfulness, and gōleós (γωλεός), a hole or pricking, referring to the absence of several cephalic pores, unique among snake eels. The specific epithet an andersoni honors the authors’ friend, who made specimens of the eel available.

In 2022, Dr. Anderson won the Robert H. Gibbs, Jr. Memorial Award for Excellence in Systematic Ichthyology by the American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists. The prize is awarded for “an outstanding body of published work in systematic ichthyology” to a citizen of a Western Hemisphere nation who has not received the award previously.

Moxostoma duquesnei. Courtesy: NCFishes.com

17 July

Moxostoma duquesnei (Lesueur 1817)