“The means for ascertaining or confirming the etymologies of many scientific names are, perhaps, not available for all who might desire to ascertain them, and they are often wrongly analyzed.”

Theodore Gill, “Fishes Living and Fossil.” Science. N.S. 3 (78): 909‒917.

Naturalists started naming animals with Latin or Latinized epithets long before Linnaeus, who formalized zoological nomenclature with his Systema Naturae (10th ed.) in 1758. Following Linnaeus’ binomial (genus and species) system, over 11,000 genus-group names and over 65,000 species-group names have been proposed for Recent fishes, with over 5,200 and 37,200 of these names, respectively, regarded as taxonomically valid today. But as Smithsonian zoologist Theodore Gill remarked back in 1896, the precise meanings of many scientific names are poorly known, and a reference for looking them up, at least among fishes, has long been unavailable. The ETYFish Project fills these voids.

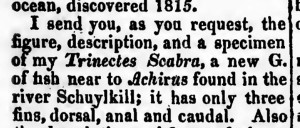

What does that name mean? My objectives are twofold: (1) to provide an English translation of a fish’s generic and specific names and (2) to explain how the name applies to the fish in question. Many references accomplish the first objective but fall short with the second. A case in point: Trinectes is a genus of coastal North and South American flatfishes whose name was coined by Rafinesque in 1832. Numerous books and websites will tell you that Trinectes is a combination of tri-, meaning three, and nektes, meaning swimmer. What most references fail to explain is what “three swimmer” actually means. (Does the fish swim in groups of three?)  The answer lies in Rafinesque’s one-sentence description: “… it has only three fins, dorsal, anal and caudal.” Clearly, Rafinesque referred to the fact that the specimen he examined (now known as T. maculatus) lacked pectoral fins (although present but rudimentary on some specimens) and, hence, had only three fins with which to swim. It’s this kind of analysis I hope makes The ETYFish Project a unique and useful reference for anyone who studies or writes about fishes or is curious about the combination of biology and language that zoological nomenclature represents.

The answer lies in Rafinesque’s one-sentence description: “… it has only three fins, dorsal, anal and caudal.” Clearly, Rafinesque referred to the fact that the specimen he examined (now known as T. maculatus) lacked pectoral fins (although present but rudimentary on some specimens) and, hence, had only three fins with which to swim. It’s this kind of analysis I hope makes The ETYFish Project a unique and useful reference for anyone who studies or writes about fishes or is curious about the combination of biology and language that zoological nomenclature represents.

In some cases, available etymological explanations are incorrect. Here is one example from among many. For over 130 years, the specific name of the Yellow Bullhead Ameiurus natalis, a catfish from North America, was believed to mean “having large nates or buttocks.” Unfortunately, this explanation is based on the incorrect assumption that natalis is the adjectival form of natis, a Latin noun for rump or buttocks. A careful examination of Lesueur’s original description, however, reveals that natalis is a Latin adjective meaning “of or belonging to birth,” often used in association with the Christian holiday of Christmas (Noel in French). By naming this catfish natalis, Lesueur was in fact honoring his fellow Frenchman and colleague, fisheries inspector Simon-Barthélemy-Joseph Noël de La Morinière (1765–1822). (See Scharpf [2020] for the full story.) Misinterpretations such as this are common in the scientific and popular literature, and are often perpetuated in subsequent publications and databases (e.g., FishBase).

A celebration of names In addition to explaining the derivations and meanings of fish names, The ETYFish Project serves another purpose: Celebrating the strictly human activity of naming things.

When a biologist describes a new taxon, the work is supposed to be clinical and objective. What does it look like? How is it structured? Where does it live? How is it different from related taxa? Where does it fit on the phylogenetic tree? Descriptive taxonomy is based on measurement, analysis and observation. It’s empirical and dispassionate, the way science is supposed to be.

But when a biologist coins and assigns a name to a taxon — the name by which they hope the taxon will forever be known — this is a rare opportunity for the scientist to be creative, personal, poetic, whimsical, even enigmatic or mysterious. Sometimes the biologist stays objective. The spotted fish is named punctatus, the tiny fish minimus, the fish from the Nile niloticus. But sometimes the biologist reveals a little bit of themselves in their selection of a name. A person they love. A colleague they admire. An allusion to a favorite book or movie. A nod to a bit of local or mythical lore.

Over the course of 43,000-plus entries, The ETYFish Project surveys and celebrates the intersection of science and creative expression that biological nomenclature often represents.

Taxonomic coverage and classification The ETYFish Project includes the names of every valid genus, subgenus, species and subspecies of fish and fish-like craniate (excluding fossils). This paraphyletic assemblage includes Myxini (hagfishes), Petromyzontida (lampreys), Chondrichthyes (sharks, rays and chimaeras), Actinopterygii (ray-finned fishes) and Sarcopterygii (coelacanths and lungfishes). Classification of higher-level taxa (subfamily and above) reflects a combination of the 5th edition of Nelson’s Fishes of the World (2016), the “Browse the Classification” page at Eschmeyer’s Catalog of Fishes, Betancur-R et al. (2017) for bony fishes, and recent revisions of individual orders and families, e.g., Tan & Armbruster (2018) for Cypriniformes, Mirande (2018) for Characidae, Girard et al. (2020) for Carangiformes, and Near & Thacker (2024) for Acanthuriformes, Centrarchiformes and Labriformes. Please note that higher-level classification is a dynamic field with many hypotheses, varied nomenclatural conventions, and no (as of yet) universal acceptance. With that said, The ETYFish Project does not aim to present or follow any definitive assessment of fish classification.

As for lower-level taxa, I provide name etymologies for all genus- and species-level taxa labeled as “valid” in Eschmeyer’s Catalog of Fishes; occasionally I add or subtract taxa when I feel that current research, or research not cited in the Catalog, justifies otherwise. I include subgenera and subspecies when my review of the literature indicates that these taxa remain in use by some ichthyologists. I recognize that many subgeneric taxa are holdovers from older morphological studies and do not necessarily represent monophyletic groupings; their inclusion here is provisional. In short, I’d rather include doubtful taxa (e.g., species inquirendae) than leave a potentially valid taxon out.

Methods Most modern-day descriptions of new fish taxa include a section on etymology in which the meaning of the name is unambiguously explained. Most descriptions from the 18th, 19th and early-20th centuries do not. When the derivation and/or meaning of a name is not explained by the author(s), such as in the Trinectes example cited above, I attempt to match my translation of the name — aided by Brown’s Composition of Scientific Words (rev. ed., 1956) and Jaeger’s Source-book of Biological Names and Terms (1959) — with an attribute mentioned in the original description. If that approach does not yield an obvious interpretation of the name, then I attempt to match the name with characters about the taxon as reported in subsequent publications. If I am not 100% certain about my interpretation, I include the adverb “probably,” “presumably” or “possibly” in the explanation.

All quotations within explanations are quoted directly from the original descriptions (see Eschmeyer’s Catalog of Fishes for citations). Non-English quotes are translated into English and indicated as such.

Despite best efforts, many names have meanings that remain enigmatic (e.g., the Kitefin Shark genus Dalatias), while others have names that reflect the whims of the author and apparently have no meaning at all. For example, Girard (1856) named several minnow genera after Native American words (e.g., Agosia, Dionda, Nocomis) simply because he liked the sound of them.

I do not mention the gender of generic names in the explanations unless it is helpful in understanding the meaning and/or proper spelling of a name; please consult Eschmeyer’s Catalog of Fishes for information on whether a name is masculine, feminine or neuter. However, following Eschmeyer’s Catalog, I insist that adjectival trivial names agree in gender with their genus names per rules of Latin grammar and will emend their spellings if necessary, as well as the terminal spellings of eponyms to agree with the gender of the person being honored.

Speaking of eponyms — fishes named after people, organizations and institutions — I seek to provide not just the name of the person or entity being honored, but also why they were honored. For many eponyms, however, the “why” is unexplained. I also include life dates (years of birth and death) when available, and any other biographical or historical tidbits I find interesting. For example, the Sharpnose Lizardfish Synodus bondi of the western Atlantic was named for ornithologist James Bond (1900–1989), who collected the holotype; the tidbit is that Bond’s name was used by writer Ian Fleming, a keen birdwatcher, for his fictional secret agent creation 007 James Bond.

A dynamic reference I will add new taxa as quickly as we can upon receipt of their publications. Likewise, I will also remove taxa if they are subsumed into synonymy, and adjust familial and generic classifications and specific placements within them as revisionary studies are published. I will also revise etymologies should new information become available.

If I overlooked a valid taxon or included one I shouldn’t have, or if you see anything you believe is incorrect or could be improved upon, please let me know. You are my peer review.

Acknowledgments My progress has been greatly facilitated by the time and labor of dozens of individuals who granted us library access, provided publications, translated non-English literature, and helped us in various ways to better understand etymologies.

- For generously sharing his time, nomenclatural expertise and PDF library, I thank R. Fricke.

- For his enormous (and anonymous) contributions to the Greek and Latin translations presented herein, proofreading, and authorship or co-authorship of special essays, I thank H. Funk.

- For interlibrary loans I thank P. J. Unmack, J. J. Hoover, R. Fricke, J. Hatch, and the library staff at the American Museum of Natural History.

- For keeping me up to date on recently described taxa and providing numerous bibliographical and etymological detective services, we thank E. Schraml.

- For proofreading many entries and “Name of the Week” essays, I thank I. J. H. Isbrücker. (Any errors that remain, of course, are mine.)

- For finding numerous taxa and taxonomic changes that I overlooked, I thank T. Lachenal.

- For sharing his personal ichthyological library, I thank T. O. Litz.

- For sharing dozens of cichlid papers from the library of Deutsche Cichliden-Gesellschaft, I thank M. E. Lippitsch.

- For access to the “fish reprint room” at the California Academy of Sciences, and fulfilling my occasional scan requests, I thank D. Catania.

- For access to the main and Division of Fishes libraries at the Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of Natural History, I thank J. M. Clayton.

- For patiently answering our questions and reviewing entries on macrouroid fishes, I thank T. Iwamoto.

- For helping me better understand enigmatic names coined by Gilbert Percy Whitley, I thank D. Hoese.

- For sharing data from their “Eponym Dictionary” research, I thank B. Beolens and the late M. Watkins.

- For locating and/or scanning/copying especially hard-to-find publications, I thank M. Endruweit, L. Finley, R. Fricke, M. Geerts, J. Hatch, P. Kukulski, C. T. Ly, D. Y. Mai, H. K. Mok, J. Müller, T. A. Munroe, T. J. Near, A. Prokofiev, E. Schraml, J. P. Sullivan, P. Tongboonkua, L. Wilson, and H. Woo.

- For general advice, help and encouragement, I thank W. N. Eschmeyer (deceased), N. Evenhuis, G. S. Helfman, R. L. Mayden, J. E. McCosker, and L. M. Page.

And, finally, for translations I thank a long list of friends, colleagues and volunteers: C. Bedford (Japanese), J. Birindelli (Portuguese, Spanish), S. Binkley (French), H. W. Choy (Chinese), A. N. Economou (Greek), M. Endruweit (Chinese), R. Fricke (Dutch, Latin), J. A. Giuttari (Latin, Italian), M. Hoang (Vietnamese), W. Hyeong (Chinese), T. James (Spanish), T. Johnson (Thai), C. T. Ly (Vietnamese), D. Y. Mai (Vietnamese), T. Maie (Japanese), M. T. Martin (Japanese), P. R. Møller (Danish), J. Nelson (Spanish), H. H. Ng (Chinese), S. V. Ngo (Vietnamese), F. O’Carroll (Japanese), A. Porcella (Spanish), A. Prokofiev (Russian, Bulgarian), M. Ravinet (Japanese), E. Schraml (German, Dutch), L. Shulov (Russian), P. Simonović (Serbo-Croation), H. Song (Japanese), Y. Vavulitsky (Russian), E. Wieser (Japanese), N. Wu (Chinese), K. Yoshida (Japanese), M. A. A. Zarazaga (Greek and Latin), and Y. Zhao (Chinese).